Key points

- Grand strategy is a state’s theory about how to provide for its own security. Leaders must decide how to best translate scarce means into political objectives. Limited resources and the high stakes of national survival force leaders to prioritize.

- Military power is dependent on wealth, industry, geographical endowments, population size, and effective domestic institutions. The various conditions in which states find themselves help motivate and constrain the grand strategy formulated by their leaders.

- The United States is still the most powerful, secure, and prosperous country in the world, with a favorable geographic position and many internal advantages. U.S. grand strategy has historically been concerned with preventing the rise of a regional hegemon in Eurasia by maintaining the balance of power.

- With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States became the only great power in the world. Unfortunately, it squandered the “unipolar moment” by pursuing a costly and counterproductive grand strategy of “liberal hegemony,” which has left it overextended.

- The United States’ secure geostrategic position and the improbability of a Eurasian hegemon allows it to adopt a grand strategy of restraint. This shift will help the United States to preserve its power, minimize risks, and adapt to the rise of new great powers. This strategy requires the United States to adopt a more rigorous definition of its vital interests and to shift to its allies the main burden of defending themselves.

What is grand strategy?

Political scientist Barry Posen defines grand strategy as “a state’s theory about how it can best ‘cause’ security for itself.”1 The largest political, military, and economic actors in the world are states.2 In an anarchical international system—where there is no world government to enforce laws or arbitrate disputes between actors—states exist in a “self-help” condition where they must provide their own security.3 Without a world government, the ultimate arbiter in international politics is the violent force that a state (or coalition of states) can exert to impose its will and defend its interests.

The famous columnist Walter Lippmann called U.S. foreign policy the “shield of the republic.”4 Among all the diverse foreign policy goals a state may wish to pursue—and the various diplomatic, economic, and cultural tools of statecraft that a state may use to pursue them—grand strategy is concerned with establishing a core set of vital security priorities that require military power. While grand strategy is at the core of a nation’s foreign policy, it is not the totality of foreign policy, which also covers policy relating to trade, immigration, and cultural and educational exchange, among other areas.

Vital security interests are those which determine the survival and autonomy of a state. These include the defense of sovereignty (domestic policymaking autonomy), the maintenance of territorial integrity, and the protection of the population.5 A state’s ability to achieve security depends on its power relative to other states, though deciding how much power is “enough” is always a source of dispute.6 A state’s power depends on material and organizational factors such as its economy, geography, demography, and state institutional capacity (tax collection, administration, etc.).

Strategy matches available means with desired ends—goals are potentially infinite, but resources are not. Strategy therefore requires prioritizing among desirable goals—creating a hierarchy of objectives to be pursued—and allocating resources accordingly. “Strategy,” as Bernard Brodie once said, “wears a dollar sign.”7 Any resources devoted to defense impose a trade-off between “guns and butter”—i.e., they come at the expense of other domestic welfare goals. As President Dwight D. Eisenhower famously put it:

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.8Therefore, the measures that states take to achieve security must be carefully balanced with the domestic goals and values of the polity. In the case of the United States, the purpose of security is undermined if its pursuit erodes fundamental aspects of American life, such as its civil liberties, democracy, and prosperity, all of which its foreign policy is supposed to defend. Formulating a strategy that ignores or abandons these domestic priorities is thus misguided.

The potentially punishing character of international politics means the system “selects” for certain types of behavior: states that fail to meet their security imperatives may cease to exist, while successful strategies encourage emulation by other security-seeking states.9 Powerful states tend to have more strategic options and a larger margin of error; less powerful states are more tightly constrained and cannot afford to make mistakes. The wide margin for error that great powers enjoy may have the paradoxical effect of making them their own worst enemies through an absence of corrective feedback, overinflated concerns over prestige, or strategic inertia.10 Foreign commitments that exceed domestic capabilities are, in Lippmann’s words, “insolvent.”11 Attempts to uphold unsustainable commitments lead to strategic overextension, eroding the domestic resources underpinning a state’s power.12

Authors often define “grand strategy” differently.13 Some even deny that states have or need a grand strategy, pointing to the disorder and inconsistent agendas among policymakers of a given state.14 However, as Edward Luttwak writes, “[a]ll states have a grand strategy, whether they know it or not.”15 Policymakers tend to share a set of common assumptions and perceptions, informing a general causal theory about security policy.16 That a grand strategy is contested, unarticulated, or poorly realized does not mean it is absent.

The United States is required by law to release regular statements of purpose pertaining to its grand strategy—the National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy. These have usually demonstrated the United States’ unwillingness in recent decades to prioritize among interests while reliably promoting increases to the defense budget.17

The elements of national power

A state’s power shapes its grand strategy, determining the problems the state must address as well as how they can be addressed. Power is determined by a state’s internal capabilities and the conditions imposed upon it by nature and fortune.

In Martin Scorsese’s crime film The Departed, Jack Nicholson’s character, a ruthless mob boss, says, “I don’t want to be a product of my environment; I want my environment to be a product of me.” The most powerful states, or “great powers,” can substantially shape aspects of their external security environment, while weaker states are vulnerable and subject to profound influence by outside powers. Increases in power tend to expand policy options and produce more ambitious goals, while weakness allows states far fewer policy options to choose from. Weaker states are therefore forced to either accommodate stronger states, form alliances against proximate threats, or find shrewd ways of pitting stronger powers against one another to survive.

Military

The threat of war is ubiquitous in international politics, and military power is the final guarantor of state survival. The actual use of force is a blunt and costly instrument of destruction and therefore only optimal for vital political objectives. The interests motivating military action should be important enough to warrant the resources demanded to successfully achieve the desired political outcome.18 Otherwise the war will likely fail to achieve its aims.

Sometimes military capabilities do not need to be actively applied through violence to realize political effects. The underlying threat of a powerful state using military force is often enough to constrain and influence the decisions of other states.

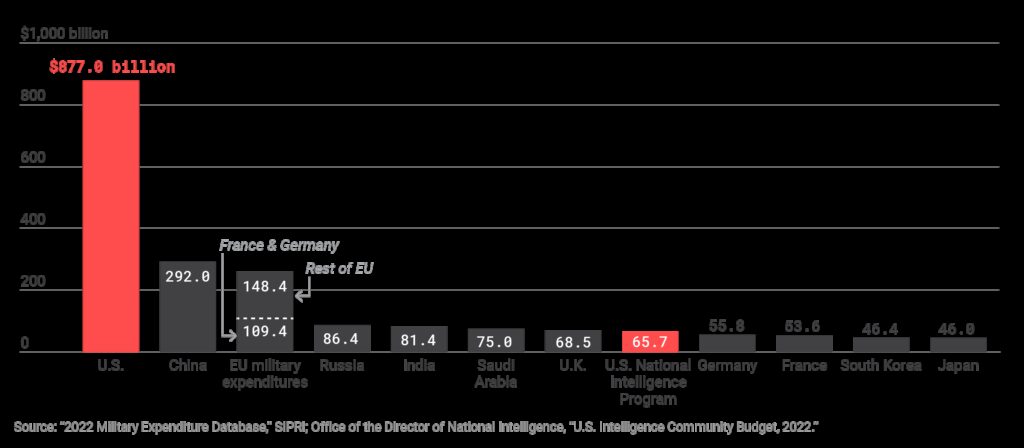

TOP military spenders (2022)

The United States spends more on its military than every other country in the world. It spends more on intelligence than most countries do on their militaries.

Military power depends on several interrelated material factors, including a country’s wealth and industrial capacity, its geographical relationship to other states, and the size and age of its population.

Economy

Economic prosperity is the foundation of national power. Wealthy states are more capable of producing or purchasing the weapons and equipment necessary for defense and sustaining their populations in both peacetime and wartime. These states tend to have technological endowments that can translate into military advantages, such as the ability to put warheads on missiles and accurately fire them across the globe. A state’s economic goals can also create secondary interests abroad, such as controlling access to critical resources, overland trade routes, or sea lanes for shipping, which great powers often seek to secure.

Just as states face a domestic trade-off between “guns and butter,” they also face a trade-off between the economic benefits of trade and the international division of labor, on the one hand, and the security benefits of economic self-sufficiency on the other. Whereas economics encourages efficiency, security often demands redundancy.19 Free trade incentivizes specialization according to comparative advantage and can therefore result in bottlenecks and chokepoints that make interdependent states vulnerable to being cut off from necessary products and resources in a conflict.20 Large, wealthy, industrialized, resource-rich states tend to be less vulnerable to external economic disruptions due to the size and diversity of their economies.

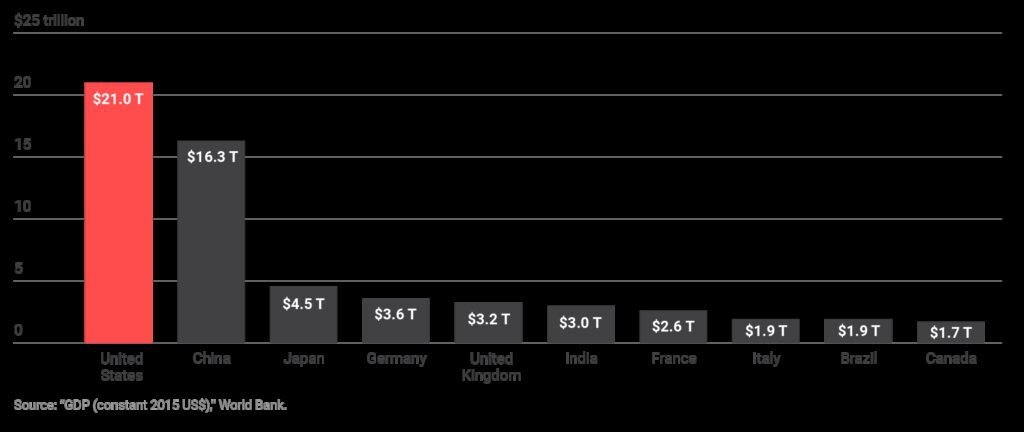

Top 10 global economies (2022)

The United States still has the largest economy in the world, thanks in part to the dominance of the U.S. dollar and the influence of the U.S. financial system.

States with a commanding position in finance or global supply chains have leverage to impose sanctions or export restrictions on target nations.21 While sanctions are painful for the populations of target states, they are rarely effective as a means of changing state behavior.22 Moreover, “sanctions-proofing” measures and the diffusion of economic power away from the West have weakened the capacity of the United States in particular to make sanctions succeed.23

Population

The size of a nation’s population determines in large part how many armed personnel can be mobilized to deter aggression or defend the country, and how many industrial workers can be mobilized to sustain the economy. Demographic trends, such as population growth and age distribution, also help shape the outlook of a state’s long-term power position. An aging population will increase resource constraints over time as the portion of the population available for armed service or work decreases and social security needs increase. Immigration may offset low birth rates and increase the population, often producing economic gains, but it can also prove controversial in domestic politics.

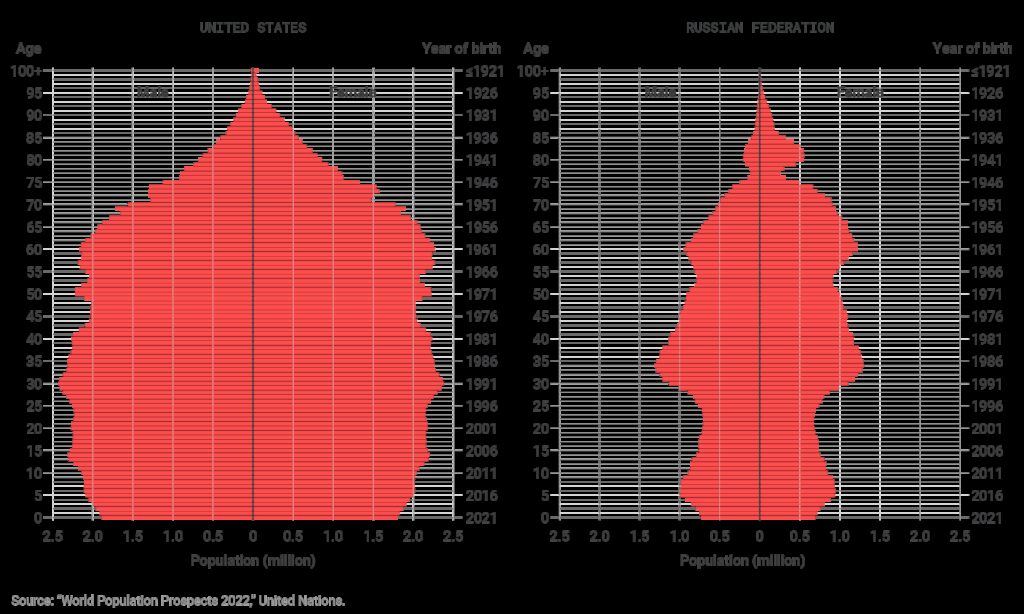

U.S. and Russian populations by age and sex (2021)

Geography

A state’s geography significantly influences its strategy. Distance from rivals insulates states from threats, while proximity to rivals heightens threats. Shared land borders across flat terrain increase the threat posed by, and vulnerability of, both bordering states, allowing for the relatively rapid movement of military forces essential for taking and holding territory, such as infantry, armored vehicles, and artillery. By contrast, natural borders such as bodies of water and mountain ranges obstruct offensive movement, raise logistical hurdles, and provide defenders with depth, cover, and time to prepare responses. Large bodies of water in particular hamper large-scale power projection, combining the inherent logistical impediments produced by distance, the challenges of transporting sufficient troops and equipment by sea, and the difficulty of conducting amphibious operations.24 States protected by natural barriers have the luxury of being able to pursue more relaxed or restrained strategies.

A state’s geography shapes how it allocates resources among its military forces: states with land borders proximate to rivals are more likely to prioritize substantial land armies, while islands or states with lengthy coastlines are more likely to prioritize substantial navies. States often wish to establish buffer zones between themselves and potential rivals and maintain control or access to vital sea lanes. Great powers often seek to neutralize weaker states on their periphery and form a sphere of influence over their neighbors to insulate themselves from potential threats.25

Domestic political factors

Many domestic political factors influence how states respond to external challenges. The ability to motivate and mobilize the population to pursue national objectives—even at risk of death—and to bear sacrifices on the home front is essential for wartime morale.26 National cohesion around a shared sense of civic identity becomes particularly important in wartime but also affects the resources the state can draw on in peacetime. The state’s relationship to society, the structure of its decision-making apparatus, bureaucracy, interest groups, and ideological and cultural dispositions all impact the formulation of a state’s national objectives and the means available to achieve them. Factors such as economic inequalities, the social pressures of industrialization, and civil conflicts can produce societal divisions that limit a state’s ability to mobilize its population and resources effectively. These forces may also push new political factions into power, leading to rapid shifts in foreign policy and possibly presenting opportunities for rivals to attack.27

Strategies in action: Japan and Russia

This dynamic combination of military, economic, geographic, demographic, and domestic factors directly affect a state’s grand strategy. For example, Japan’s seabound position as an archipelago insulates it from external assault, while its relatively small and resource-poor interior makes it dependent on maritime trade.28 Just as Britain has acted to prevent a rival from dominating the Low Countries, Japan has sought to prevent a rival from controlling the Korean Peninsula.29 Japan’s industrialization following the Meiji Restoration in 1868 created demand for raw materials from abroad and encouraged the construction of a major naval fleet, leading Japan to achieve great power status after defeating Russia in 1905. When the Japanese military gained power during the interwar period and embarked on the conquest of Manchuria, a fear of being cut off from foreign trade generated an imperialist grand strategy in the West Pacific and led to the territorial conquest of much of East Asia.30 Following its defeat in World War II and the loss of its overseas empire, Japan successfully applied a state-driven, export-oriented development model and established a sophisticated technological-industrial base under a U.S. security umbrella.31 Today, Japan possesses the third-largest GDP in the world, trailing only the United States and China.32 However, Japan’s remarkable post-war growth began to stall in the 1990s and has not fully recovered.33

While Japan has depended on the United States’ extended nuclear deterrent and the U.S. Navy to protect its sea lanes over the post-war period, there is no doubt Japan could rapidly develop its own nuclear deterrent if necessary and has the means to augment its naval forces. As a result of World War II, Japan has an ambivalent relationship with its own nationalism, yet its government has also tended to be averse to immigration. Partly due to Japan’s severe restrictions on immigration, its population has grown older, increasing constraints on its economy and military.34 Generally speaking, Japan’s conditions are excellent for territorial defense and require Japan to maintain a significant maritime capability. On the other hand, given its economic and demographic constraints, as well as the current balance of power in East Asia, Japan does not have the ability to pursue territorial conquest, especially on the Asian continent.

In contrast to Japan, Russia is a massive land power with few natural geographic boundaries, limited sea access, and more than a dozen political borders dispersed across two continents—including long land borders with both China and the world’s most powerful military alliance, NATO. A recurrent feature of Russian grand strategy has been what historian Stephen Kotkin has called “defensive aggressiveness,” seeking to exert control over its distant frontiers, subordinate neighbors to establish buffer zones and strategic depth between itself and potential adversaries, and gain warm-water ports with access to the seas.35 While Russian geography has historically made it vulnerable to invasion, its vast interior also allowed it to absorb and then repel invasions by Napoleon and Hitler, albeit at enormous cost.

During the Cold War, Russia tried to compensate for its technological disadvantage vis-à-vis the U.S. by maintaining large land forces and building up a nuclear arsenal. Its resource-rich interior and relatively large and well-educated population have been advantages, and Russia has a considerable defense-industrial base. However, the Russian state’s tendency toward over-centralization, chronic corruption, and an aging population all create significant resource constraints.36 While the Soviet Union was the second-largest economy in the post-war world, the economy of the Russian Federation today is comparable to that of Canada.37 Moreover, Russia’s enormous territory includes a diverse multinational population, which the government in Moscow has often struggled to integrate into a unified civic identity, dramatically exemplified by the Chechen insurgencies.

As a result of these factors, Russia tends to be particularly sensitive to both real and imagined foreign threats and pursues strategies that overstretch its large but limited resources.38 While Russia’s neighbors have for centuries feared the behemoth to their east, Russian forces are often tethered by domestic limitations, as the current war in Ukraine demonstrates.

U.S. grand strategy

American advantages

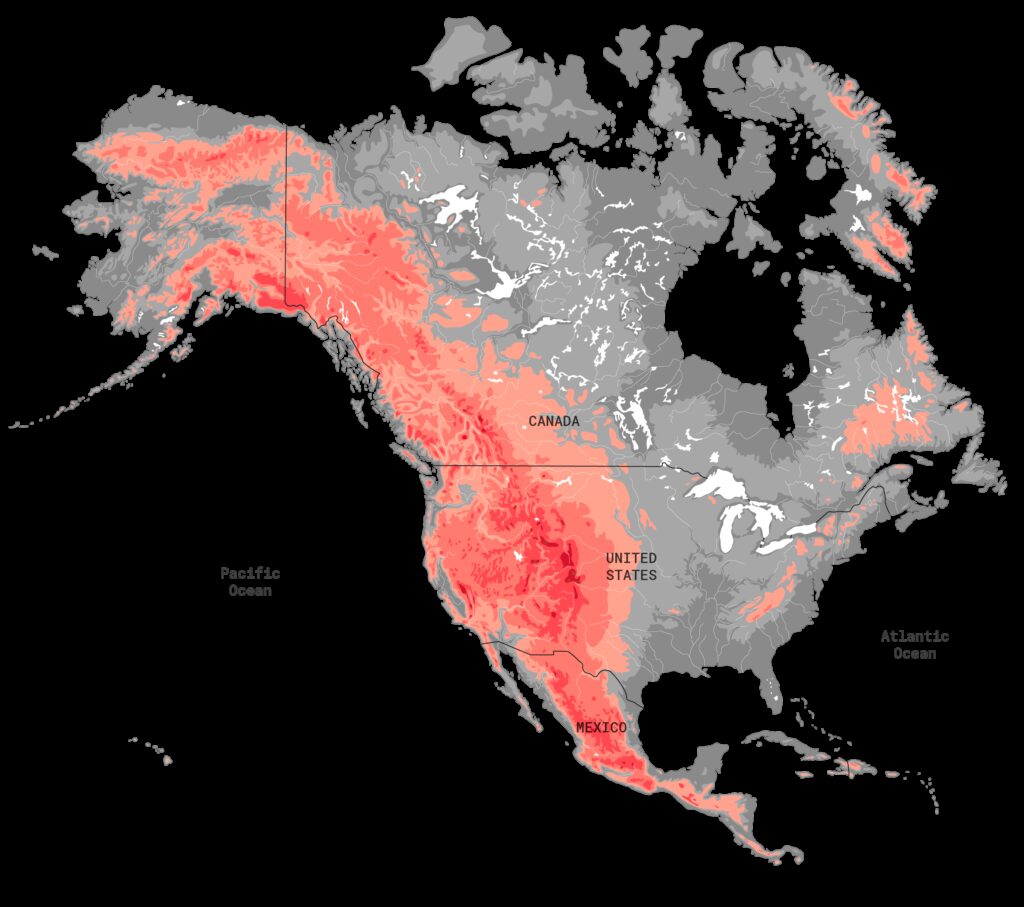

America has long enjoyed unique security advantages relative to other great powers. The United States is geographically insulated from attack, with deferential middle powers to its north and south, and vast oceans to its east and west. There are no other great powers in the Western Hemisphere, and the United States completely controls the hemisphere’s sea lanes.

Despite recent advances by other countries, particularly China, the United States still possesses the world’s most formidable and technologically advanced military. It has the only military capable of significant power projection on a global scale, as well as a robust and resilient nuclear deterrent. The United States also possesses intelligence services with unparalleled capabilities and reach: to wit, in 2022, the United States spent more on intelligence than Russia spent on its entire military budget.39

The United States enjoys, depending on the chosen measurement, either the largest or second largest economy in the world, and the U.S. dollar is the world’s primary reserve currency, allowing it to sustain large deficits and to leverage (or even weaponize) global finance.40 It is relatively insulated from disruptions to trade, with one of the world’s lowest trade-to-GDP ratios, a commanding position in global value chains, and nearly even geographic diversification of trade across major regions, with a third of its trade occurring within the Western Hemisphere.41 Additionally, the United States possesses a vast and resource-rich interior, is a net total energy exporter, and is well-placed technologically to achieve a leading role in producing sustainable renewable energy in the future.42

Topography of North America

The United States is blessed with natural physical security. Its neighbors to the north and south are friendly while open oceans to the east and west serve as large moats that make an invasion nearly impossible.

The United States is home to the world’s third-largest population.43 That population is growing and is relatively young compared to other major states like China, Russia, Japan, and Germany, whose rapidly aging populations will likely constrain their resources in coming decades.44 The United States continues to attract many immigrants, and despite periodic bouts of nativism, has generally proven adept at incorporating newcomers into a strong civic identity.

The way the United States chooses to fight its wars—and the wars it chooses to fight—are the result of several factors, including its distance from major threats, technological endowments, and domestic political institutions. The so-called “American way of war” is characterized by the United States’ reliance on its technological advantages and use of overwhelming firepower to destroy its opponents’ fighting ability rather than relatively large-scale mobilizations of combat personnel.45 This approach allowed America after the Vietnam War to maintain an all-volunteer force and incur relatively few casualties. Government spending on military research and development has in turn acted as a backdoor subsidy for cutting-edge dual-use technologies that have bolstered the United States’ position in the global consumer economy.46

However, the American way of war also underscores the fact that proximate threats to the continental United States have been virtually non-existent throughout its modern history. While President George W. Bush once said, “[w]e will fight them over there so we do not have to face them in the United States of America,” the reverse is more likely true: we can “fight them over there” because “we do not have to face them in the United States of America.”47 This is also why, despite having fought many wars in recent decades, the U.S. public remains highly casualty-averse—the interests at stake are often not worth the cost in human life.48

American grand strategy in historical perspective

For the first century of its existence, U.S. grand strategy was essentially “isolationist,” meaning it sought to keep the European great powers out of the Western Hemisphere and avoid entanglement in European conflicts.49 During the nineteenth century, the United States was a major unintended beneficiary of Britain’s management of the European balance of power and the maritime protection afforded by the Royal Navy, allowing it to focus on nation-building and expansion. By the twentieth century, however, the United States was the world’s largest and most dynamic economy, while Britain was in decline and unable to fulfill the role of “balancer” in Europe.50

The rise of Germany and Japan forced America to consider the possibility that if a hegemon were to emerge on the Eurasian landmass, it could mobilize the resources of the continent, traverse the oceans, and project significant power into the Western Hemisphere to either coerce the United States or force it to become an anti-democratic “garrison state.”51 This fear of a “Eurasian hegemon” underlay the United States’ involvement in both World Wars and its subsequent decision to contain the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The destruction of the other major world powers during World War II led the United States to deploy forces to Western Europe and East Asia and extend its nuclear umbrella to deter Soviet attacks against its allies.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of bipolarity left the United States in the unusual position of being the world’s only great power. The main threat that had justified the U.S. overseas presence had evaporated. Yet despite facing no great power rivals, the United States did not scale back its alliance commitments. On the contrary, while the U.S. reduced its troop numbers between the end of the Cold War and the Global War on Terror, it simultaneously expanded its security guarantees to other nations. The United States brought former Eastern bloc states into NATO (pushing the alliance all the way to Russia’s borders), deployed permanent forces to the Middle East to secure the flow of Persian Gulf oil, and maintained its forward military presence in East Asia. Rather than embrace the comfortable position it had acquired after the Cold War and turn swords into plowshares, the United States embarked on a remarkably ambitious global agenda—especially following the 9/11 attacks.52

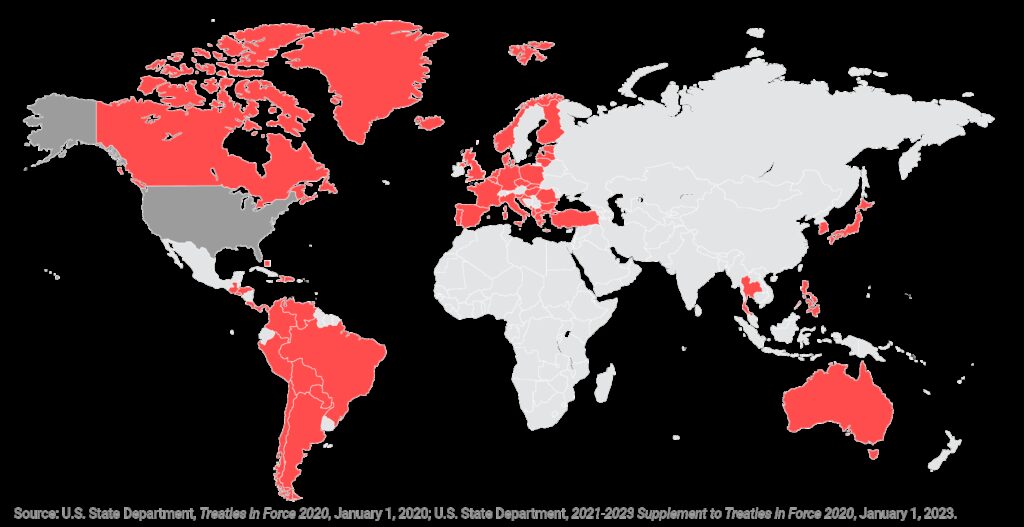

U.S. treaty allies around the world

The United States is formally committed to defending dozens of countries around the world in almost every major region. Many of these treaties were signed during the Cold War but were never updated or revised.

The United States’ post-Cold War grand strategy of “liberal hegemony” sought to cultivate a U.S.-led international order underwritten by—and in the interest of preserving—global U.S. military primacy. Military force and economic sanctions were used promiscuously (and sometimes exclusively) as instruments of statecraft toward so-called “rogue states,” including Iraq, Iran, and North Korea.53 Regime change—often in the name of protecting human rights or promoting democracy—became a popular option for Washington policymakers, leading to a series of ill-fated interventions and occupations in the Middle East that unleashed a decades-long paroxysm of chaos and bloodletting, costing millions of lives in the region (and beyond) and $8 trillion to the American public.54 Without exception, the outcomes of these interventions were contrary to U.S. interests, resulting either in a return to the status quo ante bellum (Afghanistan), descent into chaos and anarchy (Libya), gains in influence for official adversaries (Iraq), or some combination of the above (Syria).

By pursuing a policy of liberal hegemony, the United States squandered the “unipolar moment.” Even under the best of circumstances—the period of greatest relative U.S. power following the collapse of the Soviet Union—liberal hegemony not only failed but weakened the United States. In addition to being bloody and expensive failures, these interventions diverted strategic attention from emerging powers and wasted both resources and international goodwill. And while Washington sought to avoid war with major rivals, its military excesses abroad provoked other states to accelerate their efforts to counterbalance the United States, especially as the United States tested other great powers’ redlines over flashpoints like Ukraine and Taiwan. Almost all major allies remained heavily dependent on the United States—and thus enfeebled. And as the Global War on Terror has given way to a new era of great power competition, annual defense spending has continued to climb towards $1 trillion, reducing to a distant memory the “peace dividend” promised at the end of the Cold War.

Restraint: A better grand strategy

The United States is strong and safe enough to adopt a far less ambitious global strategy. It should transition to a grand strategy of restraint—one that more effectively advances U.S. interests with minimal cost, risk, and violence. This grand strategy seeks to maintain regional balances of power and eschews the unrealistic and self-defeating attempt to sustain unchallenged global military primacy. Restraint would make full use of the United States’ advantages while minimizing liabilities and would induce wealthy and capable allies to assume primary responsibility for their own defense, rather than keep them dependent on the U.S. security umbrella.55

Given its excellent power position and geographic insulation from the great powers of Eurasia, the United States remains the most secure and powerful state in world history. This gives the United States the latitude to pursue a more flexible grand strategy than other states.56 By maintaining permanent military commitments around the globe in a futile attempt to substitute for a world police force, the United States squanders its natural advantages, drains its resources, and provokes unnecessary dangers. Restraint, by contrast, would allow the United States to gracefully adapt to the rise of new powers in the decades to come, while still protecting its vital strategic interests.

Because a strategy of restraint focuses on vital national interests rather than overly ambitious projects disconnected from U.S. security, it would cost far less and would reduce defense spending considerably. However, it would also do a better job than the current grand strategy of sustaining the United States’ long-term power position by reallocating national resources more effectively. Restraint would scale back the United States’ overseas bases and land forces, instead privileging a powerful Navy able to respond to regional contingencies, if necessary, with an increased emphasis on relatively survivable submarines.57 Restraint would also seek to preserve U.S. advantages on an increasingly integrated battlefield that includes cyberspace and outer space and would continue to invest in the United States’ scientific research base.58

Restraint would not only reduce the risks and costs shouldered by the United States, but also it would allow policymakers to focus more attention on domestic needs. It would remove a pretext for the erosion of civil liberties that has accompanied the growth of a large national security state, such as the disturbing ubiquity of domestic surveillance since the 9/11 attacks.

As the world shifts toward a multipolar distribution of power, where several great powers populate the international system, the grand strategy pursued by the United States during the “unipolar moment” has become increasingly risky and self-defeating. The Sino-Russian entente and the refusal of much of the world to align with the United States and its allies over the war in Ukraine demonstrate an increasingly sharp challenge to U.S. pretensions to global leadership. Moreover, the material basis for U.S. primacy has significantly eroded. Whereas the United States accounted for about half of the world’s economic output at the end of World War II and maintained an economy twice the size of the Soviet Union’s throughout the Cold War, it currently accounts for less than a quarter of world GDP and maintains approximate economic parity with China and the EU.59 This reality constrains U.S. policy options and requires greater stewarding of its vast but finite resources.

Though the transition to multipolarity presents challenges and risks, it also presents opportunities. Multipolarity is inherently advantageous to the United States because it encourages Eurasian great powers to devote strategic attention to each other while the United States remains distant and insulated in the Western Hemisphere.60 This contradicts the conventional wisdom espoused in Washington since the end of the Cold War, but it aligns with strategic thinking in the balance-of-power tradition that has guided wise policymaking for centuries.

Maintaining permanent alliances underwritten by forward-deployed forces encourages wealthy states, like Japan and Germany, to remain security dependents rather than become capable, independent actors in their own regions, forcing the United States to accept the risks and costs of deterring threats on their behalf and put itself at risk of entanglement in otherwise avoidable conflicts.

Furthermore, dependence on the United States renders deterrence in those regions less credible—and therefore less resilient—than if its capable allies directly provide for their own defense. The inherent incredibility of extended deterrence has therefore historically encouraged American policymakers to fight unnecessary wars in the global periphery in an attempt to indirectly demonstrate U.S. resolve in regions of core interest—or at least to claim that as a rationale for foolish and unnecessary wars abroad.61 These wars, such as in Vietnam, generally entail high costs for trivial interests, driven by the dubious hypothetical causal chains of “domino theories.”62

Restraint would have the United States primarily rely on regional balances of power among local actors to prevent the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon rather than directly manage and stabilize the security of far-flung regions through a significant overseas military presence. In the unlikely event that a potential hegemon emerges and cannot be balanced by regional powers, the United States could then choose whether and how it acts to restore the balance, with the accumulated benefit of having husbanded its resources. States like Japan and Germany want to maintain their independence, not become vassals of China or Russia. It is safe to assume they will take on the lion’s share of responsibility for their own defense if threatened and if the United States stops discouraging them from doing so. By making clear it intends to reduce or remove its forward-deployed forces, the United States would incentivize capable allies to bolster their own defenses out of their inherent interest in self-preservation.

While the United States faces risks of its own making, owing largely to its overextension abroad, the direct risks it faces from other great powers are remote. The gravest potential security threat would be if China could dominate Asia and project power into the Western Hemisphere. While theoretically possible, this scenario is not probable given the obstacles China faces. These include the challenge of mounting large-scale amphibious operations; the presence of regional actors capable of balancing against China; the accessibility of relatively low-tech and inexpensive defensive systems; the durability of the United States Navy and nuclear deterrent; and formidable domestic challenges in China itself, such as demographic decline, slowing economic growth, technological challenges, and inland security problems.

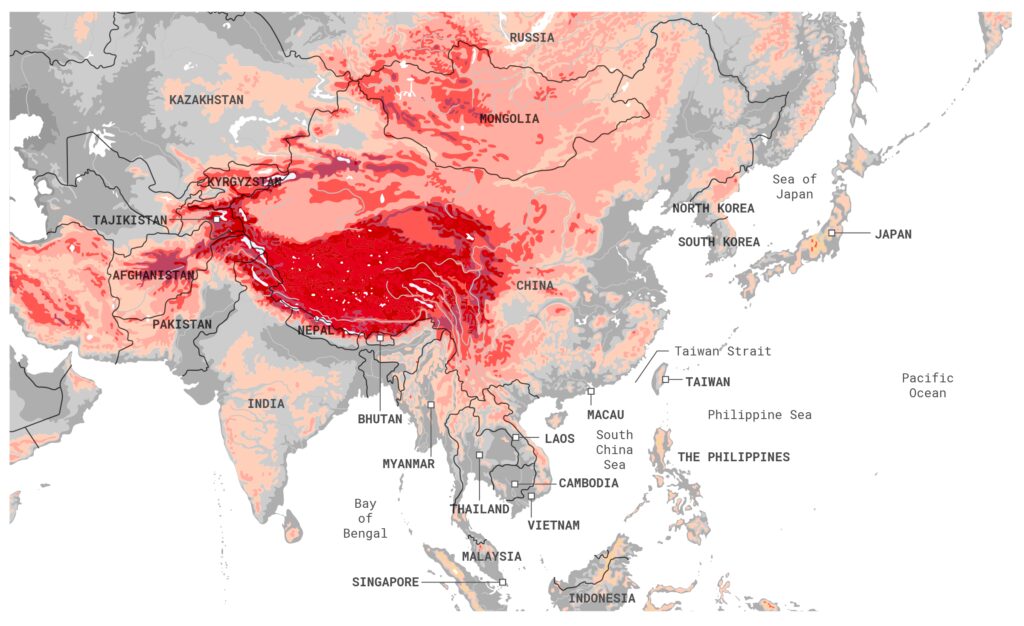

Topography of Asia

Asia’s geography is not conducive to wars of conquest and well-constituted defenders could make the costs of aggression high. The seas between Japan and the Philippines on one side and China on the other hinder territorial conquest. Similarly, the Himalayan Mountains are a major barrier between India and China that makes it difficult for either country to invade the other.

The danger to the United States of a Eurasian hegemon, while not entirely negligible, is considerably dampened by the existence of nuclear weapons and historically diminishing returns to conquest. The strength of nuclear deterrence makes the conquest of a major nuclear-armed state’s territory virtually impossible, as a nuclear war would leave little left to conquer—and no one left to conquer it. Even states with relatively small nuclear arsenals or “minimal deterrents” could impose such dire costs on a prospective aggressor that any gains from conquest would be easily nullified.63 Furthermore, the relative significance of conquering territory to seize foreign industrial regions, extractable resources, or land for agriculture and population settlement has diminished over time.64 This is particularly true for many wealthy and powerful states that draw much of their national incomes from the service sector and govern populations increasingly concentrated in urban centers.65 In addition, the stopping power of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans continues to be the greatest source of strategic depth in the world and a fundamental obstacle to any Eurasian aggression against the United States.

In short, neither China nor Russia is poised to overwhelm local rivals to dominate either region. That is good news U.S. strategy should embrace.

Therefore, while shifts in the distribution of power compel the United States to adapt to external constraints, its strategic position remains fundamentally secure and favorable relative to any other country. America stands to gain from multipolarity and need not shoulder the burden of policing the world to stay safe, free, and prosperous. While the United States should hedge against the possibility of China becoming a Eurasian hegemon and maintain a strong military on the technological cutting edge, it also has the latitude to pull back, shift burdens onto partners and allies with aligned interests, conserve and build its power, and oversee the Eurasian balance of power from a distance. The most pressing risk to the United States is its strategic overextension and its own propensity to get into unnecessary trouble.

The U.S. foreign policy establishment has yet to align itself with contemporary realities. Yet, while historically the United States has often been slow to adapt to changes in the international system, it has ultimately navigated those changes with success. The fundamentally strong and secure position of the United States has long given it a considerable margin of error in times of transition while sustaining it through periods requiring focus and resolve. Rather than wait for a major crisis to force change, the United States should make an overdue adjustment to its grand strategy. Though the United States faces significant challenges in the coming decades, it also has an unmatched ability to meet them.

Endnotes

1 Barry R. Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany Between the World Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984), 13.

2 International Monetary Fund, “Government Expenditure, Percent of GDP,” IMF Datamapper, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/exp@FPP/USA/CHN/JPN/DEU/IND/GBR/FRA/RUS/CAN/ITA. The largest private employer in the world is Walmart, with 2.3 million employees in 2022. In the same year, the U.S. government employed ten times that amount, approximately 15 percent of its total workforce. “Leading 500 Fortune Companies Based on Number of Employees in 2022,” Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/264671/top-50-companies-based-on-number-of-employees/; “Total Number of Government Employees in the United States from 1982 to 2022,” Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/204535/number-of-governmental-employees-in-the-us/; “Employment in General Government,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/b85007f1-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/b85007f1-en.

3 Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 1979).

4 Walter Lippmann, U.S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1943).

5 Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014): 1–3.

6 Posen, Restraint, 3. For the argument that power and security are only synonymous up to a point, beyond which counterbalancing occurs and the pursuit of power becomes self-defeating, see Waltz, Theory of International Politics, 125–127. For an argument that power maximization is synonymous with security maximization, see John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2001), 19–22, 29–40. For discussions, see Christopher Layne, The Peace of Illusions: American Grand Strategy from 1940 to the Present (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006), 19–25; Barry R. Posen, “The Best Defense,” National Interest, no. 67 (Spring 2002): 119–126.

8 Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Address ‘The Chance for Peace’ Delivered Before the American Society of Newspaper Editors,” American Presidency Project, April 16, 1953, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-chance-for-peace-delivered-before-the-american-society-newspaper-editors.

9 Waltz, Theory of International Politics, 73–77.

10 Robert Jervis, “Unipolarity: A Structural Perspective,” World Politics 61, no. 1 (January 2009): 188–213.

11 Lippmann, U.S. Foreign Policy, 8–10.

12 For a famous articulation of this phenomenon, see Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (New York, NY: Random House, 1987).

13 For various definitions of grand strategy, see Edward Mead Earle, “Introduction,” in Makers of Modern Strategy: Military Thought from Machiavelli to Hitler, ed. Edward Mead Earle (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1943), vii-xi; Bernard Brodie, “Strategy as a Science,” World Politics 1, no. 4 (July 1949): 477, f.10; B.H. Liddell Hart, Strategy: Second Revised Edition (New York, NY; Meridian, 1991), 353–360; Paul Kennedy, “Grand Strategy in War and Peace: Toward a Broader Definition,” in Grand Strategies in War and Peace, ed. Paul Kennedy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), 1–10; Lawrence Freedman, “Grand Strategy in the Twenty-First Century,” Defence Studies 1, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 11–20; Williamson Murray, “Thoughts on Grand Strategy,” in The Shaping of Grand Strategy: Policy, Diplomacy, and War, ed. Williamson Murray, William Hart Sinnreich, and James Lacey (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 1–33.

14 For arguments that the United States does not need nor have the ability to form a coherent grand strategy, see Daniel W. Drezner, Ronald R. Krebs, and Randall Schweller, “The End of Grand Strategy: America Must Think Small,” Foreign Affairs 99, no. 3 (May/June 2020): 107–117.

15 Edward N. Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 409.

16 For some influential analyses of leaders’ cognitive mapping, see Ole R. Holsti, “The Belief System and National Images: A Case Study,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 6, no. 3 (September 1962): 244–252; Alexander L. George, “The ‘Operational Code’: A Neglected Approach to the Study of Political Leaders and Decision-Making,” International Studies Quarterly 13, no. 2 (June 1969): 190–222; Jack L. Snyder, “The Soviet Strategic Culture: Implications for Limited Nuclear Operations,” RAND Corporation, September 1977, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2005/R2154.pdf.

17 Justin Logan and Benjamin H. Friedman, “The Case for Getting Rid of the National Security Strategy,” War on the Rocks, November 4, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/11/the-case-for-getting-rid-of-the-national-security-strategy/.

18 For example, during and after World War II the United States was willing to devote the enormous resources needed to help defeat Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, to aid the post-war reconstruction of Western Europe and Japan, and to deter the Soviet Union. This is because the United States deemed these measures to be absolutely vital to its national security objectives. By contrast, after the Cold War, the United States sought to conduct its many elective interventions in the Middle East with a “light footprint,” quickly, and cheaply. This betrayed a lack of vital interests at stake. Unsurprisingly, these interventions were all failures according to their stated objectives, turned into endless quagmires or “forever wars,” and proved far more costly over time than their planners ever anticipated at the outset.

19 Edward N. Luttwak, Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), 39–42. For example, whereas China has long depended on a “minimal” nuclear deterrent, escalating great power competition has spurred Beijing to pursue a nuclear buildup in order to have enough missiles and platforms to absorb a potential nuclear first strike.

20 For example, the near monopoly of TSMC over advanced semiconductor production makes the global economy vulnerable to a disruption if a conflict broke out over Taiwan; consequently, much of the world is racing to “onshore,” or build their own semiconductor manufacturing capacity. See Christopher McCallion, “Semiconductors Are Not a Reason to Defend Taiwan,” Defense Priorities, October 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/semiconductors-are-not-a-reason-to-defend-taiwan.

21 See for example Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion,” International Security 44, no. 1 (Summer, 2019): 42–79.

22 Robert A. Pape, “Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work,” International Security 22, no. 2 (Fall, 1997): 90–136.

23 See for example Nicholas Mulder, “Sanctions Against Russia Ignore the Economic Challenges Facing Ukraine,” New York Times, February 9, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/09/opinion/sanctions-russia-ukraine-economy.html.

24 For a discussion of “the stopping power of water,” see Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, 114–128.

25 Andrew Latham, “Spheres of Influence in a Multipolar World,” Defense Priorities, September 26, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/spheres-of-influence-in-a-multipolar-world.

26 See, for example, Barry R. Posen, “Nationalism, the Mass Army, and Military Power,” International Security 18, no. 2 (Fall 1993): 80–124.

27 Stephen M. Walt, Revolution and War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996).

28 For discussions of Japanese grand strategy in historical perspective, see Michael J. Green, Line of Advantage: Japan’s Grand Strategy in the Era of Abe Shinzo (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2022), 16–44; Richard J. Samuels, Securing Japan: Tokyo’s Grand Strategy and the Future of East Asia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), 13–37.

29 Green, Line of Advantage, 23–24.

30 D. Clayton James, “American and Japanese Strategies in the Pacific War,” in Makers of Modern Strategy: from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986), 703–732.

31 Chalmers Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925–1975 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1982).

32 “GDP (current US$),” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?most_recent_value_desc=true.

33 “GDP Growth (annual %) – Japan,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=JP.

34 For one particularly illustrative example, adult diapers outsell baby diapers in Japan by 2.5 times. Markus Bell, “Japan’s Self-Destructive Immigration Policy,” Diplomat, January 4, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/01/japans-self-destructive-immigration-policy/.

35 Stephen Kotkin, “Russia’s Perpetual Geopolitics,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 3 (May/June 2016): 2–9. Also see Robert H. Donaldson and Joseph L. Nogee, The Foreign Policy of Russia: Changing Systems, Enduring Interests, 4th ed. (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2009), 16–33.

36 Kotkin, “Russia’s Perpetual Geopolitics.”

37 “GDP (current US$),” World Bank.

38 Michael Kofman, “Drivers of Russian Grand Strategy,” Russia Matters, April 23, 2019, https://www.russiamatters.org/analysis/drivers-russian-grand-strategy.

39 Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “U.S. Intelligence Community Budget,” https://www.dni.gov/index.php/what-we-do/ic-budget; “Military Expenditure,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, https://www.sipri.org/research/armament-and-disarmament/arms-and-military-expenditure/military-expenditure.

40 “GDP (current US$) – United States, China,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=US-CN&most_recent_value_desc=true; “GDP, PPP (current international$) – United States, China,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.PP.CD?locations=US-CN.

41 “Trade (% of GDP),” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS?name_desc=false; World Trade Organization, “United States: Trade in Value Added and Global Value Chains,” https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/miwi_e/US_e.pdf; Office of the United States Trade Representative, “Countries and Regions,” https://ustr.gov/countries-regions. Also see Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “The Effects of Wars on Neutral Countries: Why It Doesn’t Pay to Preserve the Peace,” Security Studies 10, no. 4 (Summer 2001): 1–57.

42 U.S. Energy Information Administration, “U.S. energy facts explained,” https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/imports-and-exports.php; Benjamin Storrow, “In a First, Wind and Solar Generated More Power than Coal in U.S.,” Scientific American, June 12, 2023, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/in-a-first-wind-and-solar-generated-more-power-than-coal-in-u-s/.

43 “Population, total,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?most_recent_value_desc=true.

44 United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects 2022: Graphs and Profiles, https://population.un.org/wpp/Graphs/; Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook: Country Comparisons – Population growth rate, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/population-growth-rate/country-comparison; Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook: Country Comparisons – Median age, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/median-age/country-comparison.

45 For discussions of the “American way of war,” see Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War: A History of United States Military Strategy and Policy (New York, NY: Indiana University Press, 1973); Antulio J. Echevarria II, Reconsidering the American Way of War: US Military Practice from the Revolution to Afghanistan (Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2014).

46 See for example, The White House, “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Renewing American Economic Leadership at the Brookings Institution,” April 27, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/04/27/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-on-renewing-american-economic-leadership-at-the-brookings-institution/.

47 George W. Bush, “President Bush Addresses the 89th Annual National Convention of the American Legion,” August 28, 2007, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2007/08/20070828-2.html.

48 Harvey M. Sapolsky and Jeremy Shapiro, “Casualties, Technology, and America’s Future Wars,” Parameters 26, no. 2 (Summer, 1996): 119–127.

49 For a sympathetic treatment of a much-maligned term, see Charles A. Kupchan, Isolationism: A History of America’s Efforts to Shield Itself from the World (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2020).

50 For a classic account of nineteenth century balance of power politics and the rise of new powers at the turn of the century, see A.J.P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1954).

51 See, for example, George F. Kennan, American Diplomacy, 1900–1950 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1951), 4–5; Hans J. Morgenthau, In Defense of the National Interest: A Critical Examination of American Foreign Policy (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1951), 5–7. Stephen Van Evera has referred to this as the “political division of industrial Eurasia.” See Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe Matters, Why the Third World Doesn’t: American Grand Strategy After the Cold War,” Journal of Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (1990): 2–4. Also see George F. Kennan, “Contemporary Problems in Foreign Policy,” speech to the National War College, September 17, 1948, George F. Kennan Papers, Princeton University Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, https://findingaids.princeton.edu/catalog/MC076_c03141. On Kennan’s strategic thought, see John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy During the Cold War, rev. and expanded ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005), 24–86. For discussions of the “garrison state,” see Harold D. Lasswell, “The Garrison State,” American Journal of Sociology 46, no. 4 (January 1941): 455–468; Aaron L. Friedberg, In the Shadow of the Garrison State: America’s Anti-Statism and its Cold War Grand Strategy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).

52 For expressions of the post-Cold War zeitgeist, see Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” National Interest, no. 16 (Summer 1989): 3–18; Charles Krauthammer, “The Unipolar Moment,” Foreign Affairs 70, no. 1 (1990/1991): 23–33; Samuel P. Huntington, “Why International Primacy Matters,” International Security 17, no. 4 (Spring, 1993): 68–83.

53 More than a quarter of the United States’ nearly 400 foreign interventions since its founding have occurred since the end of the Cold War. Sidita Kushi and Monica Duffy Toft, “Introducing the Military Intervention Project: A New Dataset on US Military Interventions, 1776–2019,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 67, no. 4 (April 2023): 752–779.

54 Costs of War Project, “Summary of Findings,” Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/papers/summary.

55 For major statements of restraint, see Eugene Gholz, Daryl G. Press, and Harvey M. Sapolsky, “Come Home, America: The Strategy of Restraint in the Face of Temptation,” International Security 21, no. 4 (Spring 1997): 5–48; Layne, Peace of Illusions, 159–192; Posen, Restraint.

56 Robert Art refers to both isolationism and offshore balancing as “free hand” strategies. Restraint is similarly a free hand strategy. Robert J. Art, A Grand Strategy for America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003), 172.

57 Posen, Restraint, 135–163.

58 Posen, Restraint, 135–163.

59 Central Intelligence Agency, “A Comparison of Soviet and US Gross National Products, 1960–1983,” August 1984, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000498181.pdf; “GDP (current US $) – United States, World,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=US-1W.

60 Layne, Peace of Illusions, 24–26.

61 Layne, Peace of Illusions, 124–133.

62 See the essays collected in Dominoes and Bandwagons: Strategic Beliefs and Great Power Competition in the Eurasian Rimland, ed. Robert Jervis and Jack Snyder (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991).

63 Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989).

64 Carl Kaysen, “Is War Obsolete?: A Review Essay,” International Security 14, no. 4 (Spring, 1990): 48–57.

65 Stephen Van Evera, “Primed for Peace: Europe After the Cold War,” International Security 15, no. 3 (Winter 1990–1991): 14–16.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News