The 1994 Washington Agreement ended fighting between Bosniak and Croat forces, but in the historic city of Mostar, people’s everyday lives and the local political scene are still troubled by the legacy of the wartime past.

Only a few passers-by are to be seen early in the morning on what’s known as Fejiceva Street in Mostar’s mainly stone-built Old Town. The paving stones along the street, polished by millions of footsteps and soaked by the heavy rain that had been falling for three nights in a row, are causing a hazard for pedestrians.

A ten-minute walk away in Spanish Square, the picture is completely different. Despite the early hour, the streets are full of locals doing errands or going to work, pupils heading for school and people walking at double speed because they’re running late.

Fejiceva Street, officially called Brace Fejic Street, is located on the east bank of the Neretva River, which divides the southern Bosnian conurbation into two parts. Spanish Square is in the larger west bank area of Mostar, which is often referred to as a de facto divided city.

This description was cemented three decades ago, on March 18, 1994, when the Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks agreed to end the violence by signing the so-called Washington Agreement. The agreement ensured a ceasefire which came into force on April 1 that year, but it also resulted in the effective division of the city along ethnic lines, which has continued up to the present day.

Following the 1994 agreement and after the end of the war, Bosniaks settled on the east bank of the Neretva river, while most of the Croats in the city moved to the west bank.

To the untrained eye, there is no visual difference between the east and west banks. But those who live in Mostar say that wartime divisions are “still alive in some people’s heads”.

“As long as we have Izetbegovic, Covic and Dodik, it will remain the same,” Mehmedalija Mekic, known in Mostar by the nickname Guma (Tyre), told BIRN in one of the coffee shops in the city’s Old Town.

Bakir Izetbegovic, Dragan Covic and Milorad Dodik, the politicians mentioned by Mekic, are leaders of the biggest Bosniak party, the Party of Democratic Action, SDA, the biggest Croat party, the Croatian Democratic Union, HDZ and biggest Bosnian Serb party, the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats, SNSD.

Mekic, now 72, was in the military police during the war and served as second-in-command in the city of Mostar. He was part of the Bosniak-led Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

At the beginning of the 1992-95 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mostar saw three forces fighting each other on various fronts – the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Croat-led Croatian Defence Council, HVO, and the Serb-led Army of Republika Srpska.

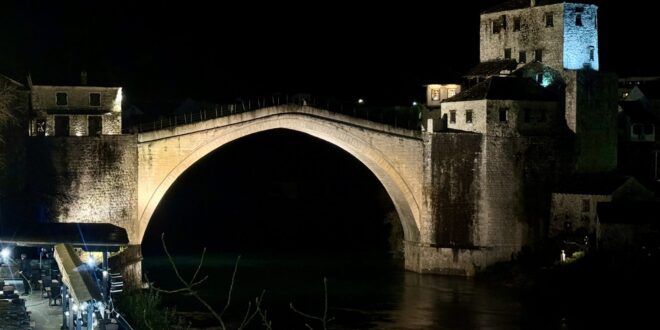

Around 2,000 people died, while more than 90,000 left the city. Mostar was hit by some 100,000 artillery shells, and many buildings including the historic Old Bridge over the Neretva were destroyed.

The 1994 Washington Agreement ended the conflict between the HVO and the Bosnian Army, uniting them in the fight against the Bosnian Serbs until the end of the war the following year.

The Washington Agreement also divided the territory that was held by Croat and Bosnian forces into ten autonomous cantons, establishing the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity, which continues to exist today. The cantonal system was chosen to prevent any ethnic group from achieving dominance over another – but also cemented the divisions that continue to exist in places like Mostar.

Much-needed respite for Mostar

While BIRN was talking to Mekic, who is loud and cheerful by nature, he greeted someone on the street with a hearty invitation to sit down and have a cup of coffee.

The man who entered the coffee shop was Smail Klaric, who was the president of the wartime presidency of the city of Mostar – the wartime equivalent of the mayoralty. Today, Klaric is 85, but still maintains an upright military stance.

“One of the first things we did when the war came was to implement a curfew during the daytime hours, as people were dying on the street at that time,” he recalled as he joined in the conversation.

“In 1993, things got really serious,” he continued. “We were blocked off from the rest of the territory controlled by the Bosnian Army, and we were constantly short of supplies and food.”

Klaric and Mekic both witnessed how a UN convoy carrying medicines was obstructed for nearly two months from reaching Mostar by Bosnian Croat forces until it finally arrived on August 21, 1993. However, it took the convoy five more days to reach the Muslim quarter in the east of the city.

After the convoy got through, local Bosniaks initially prevented the UN personnel from leaving again in order to deter the HVO from shelling. “The people had to do it,” Mekic insisted. “We were dividing up the food and giving to the people who were living closer to the frontline [because there wasn’t enough for all],” Klaric added.

“I remember that before the convoy arrived, I had not eaten for three days, while people close to the frontline, which was some 200 metres from the west bank of the river, were given double portions so as they didn’t leave their positions,” he explained.

Mekic interjected with a question for Klaric. “Do you remember that we only had rice with powdered protein for three months?” he asked.

On August 28, the UN vehicles were allowed to depart, but only after Spanish soldiers agreed to stay in the Muslim-controlled sector of the city to discourage further attacks by the Bosnian Croats.

“When the Washington Agreement was signed, the city got a much-needed respite,” Klaric added. It also meant that people then had a chance to leave Mostar, and many did.

‘Still living in fear of the past’

On the west side of the city, which is mostly populated by Croats, many are not keen to speak publicly about the war or about today’s continuing divisions. Most say that people from different ethnic groups do meet, hang out and participate in joint activities – but not always.

People remain divided by difficult questions such as the destruction of the Old Bridge and other buildings by the HVO’s shelling and the ethnically-linked political turmoil that left Mostar politically paralysed for years and run by a de facto acting mayor from the HDZ, whose administration wasn’t able to resolve the ever-rising number of public service problems. The city did not have elections from 2008 until 2020, when the country’s main Bosniak and Croat parties finally struck a breakthrough deal on how to govern.

Two people who did agree to speak on the west bank were an elderly couple, 74-year-old Huso and 70-year-old Nermana Catovic, Bosniaks who decided to move back to their apartment in the Croat part of the city.

“As soon as the Washington Agreement was signed, we left the city as refugees and went to Turkey,” Huso Catovic told BIRN during the couple’s morning stroll around the city.

“We were not sure if the ceasefire would actually stay in place, and did not want to risk everything,” he added.

The Catovics moved back to Mostar in 2014 after reaching retirement age. They renovated their old apartment prior to coming back.

“Even talking about this publicly, I’m afraid that someone might come and break my window,” Huso Catovic said, pointing up at the first floor of a nearby apartment building.

Thirty years have passed since the Washington Agreement ended the fighting over Mostar, but for some people in the city, a sense of unease persists even today.

“I really hope that you young people will carry on the change in this city and the country, as we, the older ones, are still living in fear of the past,” Catovic said.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News