The Key to Both Goals Is Going After Hamas in Rafah

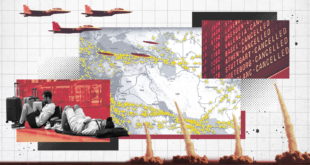

In the wake of Iran’s attack on Israel with hundreds of drones and missiles last weekend, Israel must decide how to calibrate its response. The spectrum of possible actions is wide and includes strikes on Iranian interests outside Iran and targets inside its borders.

Israeli leaders faced a similar decision after the Hamas attacks of October 7. Back then, the question was whether they should respond to the Hamas attack primarily by sending troops to Gaza with the goal of ending Hamas’s domination of that territory and its ability to threaten Israel militarily, or also (or instead) pursue Israel’s more powerful and dangerous adversary to the north, the Iranian-backed Lebanese militant group Hezbollah—even though it was not directly involved in the October 7 attacks. Israel chose the first option, a decision that has shaped the conflict to this point.

The question for the Israeli leadership now is which steps against Iran would demonstrate resilience and maintain credibility without escalating the conflict into a full-scale war. One part of Israel’s response must be to stay the course in the Gaza Strip, despite tremendous pressure from the United States and others to retreat into what would amount to a strategic surrender. In practice, that means proceeding with plans for the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) to enter the southern Gaza city of Rafah, eliminate the Hamas brigades and leaders based there, and deepen planning for a “day after” in Gaza and a long-term resolution to the conflict with the Palestinians that is predicated on reality rather than on American fantasies about a “two-state solution” that represents no solution at all.

WHY RAFAH MATTERS

The argument for taking on Hezbollah after October 7 was that the Hamas attack had proved that Israel needed to defang its enemies rather than imagine it was deterring them or had achieved a permanent modus vivendi with them. Military leaders, including Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, reportedly favored that option. But Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former defense minister and IDF chief of staff Benny Gantz overruled Gallant, and the war cabinet decided that the immediate target must be Hamas and not Hezbollah.

An Israeli attack on Hezbollah in Lebanon would have brought immense destruction to both countries, and the pressures on the IDF to curtail its operations there would likely have been greater than those it has faced regarding Gaza. In 2006, Hezbollah attacked Israel, and the George W. Bush administration, in which I was serving at the time, gave the Israelis strong support—but only for a couple of weeks, after which Washington pressured Israel to end the war by extending assurances that have never been met and never seemed likely to be. The terms of UN Security Council Resolution 1701, which was passed in August 2006, included an end to arms transfers by any state to Hezbollah and total Lebanese army control of Lebanon’s south. Neither stipulation has ever been enforced—a testament to the dangers of relying on a paper peace rather than conditions on the ground. Israel learned the lesson.

That is why it is resisting international pressure, especially from Washington, for a cease-fire that would leave Hamas in control of parts of Gaza, with its high command intact and able (with Iranian help that would surely be forthcoming) to regenerate a fighting force that could once again threaten Israel. Netanyahu has pledged to continue the attack on Hamas. Israel is pursuing a temporary cease-fire that would free some Israeli hostages in Gaza and Hamas prisoners in Israeli jails, but Netanyahu is intent on returning to the fight against Hamas after that. Israel believes that the Hamas military leadership and its remaining four battalions of organized troops are in or near Rafah and that the full defeat of Hamas requires attacking them there, even if the fighting and civilian casualties arouse harsh American and international criticism.

Despite that risk, Israelis across the ideological spectrum agree that Hamas must be crushed because they see the fight against the group as an existential conflict. Hamas can’t destroy Israel by itself, but all of Israel’s enemies are watching to see whether Israel can fully recover from the October 7 attack. If they conclude that it cannot, the Jewish state will find itself in mortal peril. Israelis saw the astonishingly brutal Hamas attack, reminiscent of anti-Semitic pogroms and the Holocaust in its treatment of Jewish men, women, and children, as a test of who will prove to be more resilient, the Jews or their murderers.

Israel gained Arab partners in the region through demonstrations of strength, not acts of restraint. It has watched Iran work with proxies to build what Israeli officials call “a ring of fire” around Israel: the Houthis in Yemen, Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and militants in Iraq and Syria. At the same time, Israel has seen a substantial increase in the volume of weapons being smuggled into the West Bank.

All of Israel’s enemies are watching to see whether Israel can fully recover from the October 7 attack.

Israelis are weary of being lectured about how war cannot destroy an idea—including by governments that joined together to crush the Islamic State terrorist group, also known as ISIS. That group also represented an idea, but without territory to govern and from which to launch attacks and build its empire safely, its power has nearly evaporated. ISIS isn’t gone, as its recent attack in Moscow showed, but the level of threat it represents is much lower.

The same would apply to Hamas: as part of the Muslim Brotherhood movement and as a group determined to use the murder of Jewish Israelis as a political tool, it will no doubt survive and commit occasional acts of terrorism. But its ability to wound Israel as it did on October 7 depended on controlling space in which it could build its finances, train its forces, and organize attacks. If Israel’s war in Gaza succeeds, Hamas will never again have all of that.

That is why an assault on Rafah will eventually be necessary. If Hamas battalions and leaders based there survive, Israel will lose the war. And that is an outcome the United States should fear. After the chaotic 2021 U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and amid the slowing of American military aid to Ukraine, Washington cannot afford to further undermine any of its alliances—or raise doubt in the minds of U.S. adversaries in China, Iran, and Russia (and U.S. allies in Asia and Europe) about the strength of American commitments and the efficacy of U.S. support. The extensive and effective assistance that the United States provided to Israel in defeating Iran’s recent aerial attack does not change this fact because that assistance was purely defensive. If it is followed by American demands that Israel allow Hamas to survive in Gaza and that it not respond to the Iranian assault, the Israelis will understand that the U.S. policy objective is simply to avoid or quickly end any conflict. That won’t be reassuring to countries facing Chinese, Iranian, or Russian aggression.

It is also worth noting that publicly applied American pressure on Israel over Rafah is reducing the chances for a hostages-for-prisoners deal. Every time high officials in the United States government (including in Congress) and other Western governments demand an immediate cease-fire in Gaza and discourage an Israeli assault on Rafah, they raise the price that Hamas believes it can demand for the hostages. The group’s only true incentive for agreeing to release them is its hope to delay an Israeli attack on Rafah or avoid one altogether. For Hamas, survival is victory. And if there is no Israeli attack on Rafah, Hamas will survive.

EVERYONE’S A CRITIC

Israel must destroy the Hamas military threat from Gaza and, to the extent possible, minimize collateral damage to Palestinian civilians. Whether it has done the latter is a fair question, but critics are not asking it fairly. “The extent possible” should suggest comparisons with other recent wars and especially other recent instances of urban combat. Instead, as usual, critics are holding Israel to standards that they impose on no other country. For example, the ratio of civilian-to-military casualties in Gaza seems better than what the United States achieved during the Iraq war. The notion that Israeli attacks deliberately target civilians, even aid workers, is belied by the fact that the IDF is a citizens’ army. With hundreds of thousands of civilian reservists serving in the army, it is simply not credible that orders to attack civilians and aid workers would be followed and would remain secret if they existed.

The truth is that Hamas wants civilian casualties because it correctly judges that such suffering will quickly lead to pressure on Israel to stop fighting. Hamas’s astonishingly large and sophisticated tunnel system in Gaza was not built to save a single civilian life but only to help protect the group’s leaders and fighters and to aid its offensive capabilities. American, European, or other leaders who ignore all of this are turning “to the extent possible” into an impossible bar that would make defeating Hamas impossible.

This is not to say that Israel has done everything it can to protect and feed civilians in Gaza. The United States and many other countries have criticized Israeli conduct in this regard, and the Israelis have admitted some mistakes and have recently begun to facilitate more food going into Gaza. But it is worth noting that many of the countries denouncing Israel have themselves done precious little thus far on behalf of Palestinian civilians. For example, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) built a refugee camp for some 80,000 Syrian refugees in Jordan. Why not in Gaza? The same goes for the European Union, which could build tent cities for temporary refuge.

Such activities cannot be undertaken in combat zones, but they can be planned and pledged now, and donors could already be working with Israel to identify locations in Gaza where combat has already ended or will end soon. Even taking all the obstacles into account, it is telling that neither the EU nor the UAE—nor other putative supporters of the Palestinians, such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia—has even floated these possibilities. Likewise, Egypt has provided safe haven to handfuls of Gazans instead of the tens of thousands it could absorb temporarily.

And what about the United States? Its airdrops of aid appear to be little more than gestures of goodwill. The Biden administration’s plan to build a temporary port off the Gazan coast for ships ferrying food from Cyprus could be a useful contribution, but there has been little discussion of who will distribute that food once it arrives on land.

THE DAY AFTER

American critics have also complained about Israel’s lack of focus on “the day after” in Gaza. It’s debatable whether the U.S. failure to carry out postwar planning before invading Iraq in 2003 gives Washington more or less credibility on that issue. Equally debatable is whether Israel should be expected and relied on to develop and implement postwar plans or should give way to efforts by the United States and other potential donors. But it does seem reasonable to expect that some kind of plan would be in place by now.

Earlier this year, I participated in a study group organized by the Jewish Institute for National Security of America and a network of foreign policy experts called the Vandenberg Coalition, which called for countries committed to a peaceful, demilitarized, deradicalized Gaza—including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the United States—to establish an international trust to reconstruct Gaza and provide relief. The trust would marshal funds going to Gaza; coordinate with Gazans in the diaspora and in Gaza to restore essential services and begin reconstruction; work with Israel on security, border control, and other matters; and cooperate with international organizations and nongovernmental organizations committed to the same goals.

There’s no easy answer to the question of who should provide security in a post-Hamas Gaza. It would most likely come from a combination of vetted non-Hamas police personnel in Gaza; new forces that the United States would train at its existing training center for Palestinian security forces, in Jordan; personnel from Arab countries that would be establishing refugee camps, tent cities, or other new residential areas in Gaza and might be willing to protect what they’re building; and private security companies that would protect food convoys, warehouses, residential areas, and other important locations. It would also be possible to give local civic and business groups or prominent Gazan clans some security responsibilities, if they have or can create the capacity to keep the peace locally.

Before the war, when Hamas was in charge of Gaza, there was a civilian structure there performing many normal governmental activities such as providing electricity and water and carrying out nonpolitical police work, such as traffic control. The international trust would aim to rebuild that structure but without Hamas on top. The top two or three layers of officials in every ministry must go, but it is likely that underneath those layers are competent professionals without any deep allegiance to Hamas. The Palestinian Authority (PA), on the other hand, cannot govern Gaza, given its own weaknesses, ineffectiveness, inefficiency, corruption, and vast unpopularity among Palestinians. The international trust itself would probably have to function in many ways as the government of Gaza for years.

Whoever governs Gaza, deradicalization will be critical to future peace. Schools run by Hamas, the PA, and the UN aid agency UNRWA have idealized terrorism and taught hatred to a generation of Palestinians, as have religious leaders in mosques throughout Gaza. Several Arab countries—Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, for example—have led the way on deradicalization. International donors to postwar Gaza must insist on entirely new curricula in schools, the vetting of teachers, and preventing mosques from being used to preach violence, terror, and hatred.

THE JORDANIAN OPTION

Relief and reconstruction in Gaza will not settle the long-term problems that drive the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The conventional solution, of course, is the so-called two-state solution. But that is the wrong answer. First, polls make it clear that both Israelis and Palestinians are highly unenthusiastic about and wary of the idea. Gallup polls conducted since late last year found that 65 percent of Israeli respondents opposed the two-state solution and only 25 percent supported it. The gap is even larger among Palestinians; in polls that Gallup conducted last summer, before the October 7 attacks, 72 percent of Palestinian respondents opposed the two-state solution and only 24 percent supported it. Second, the PA lacks the ability to lead a Palestinian state that would be free and democratic, have a decent and effective government, and build a prosperous economy. In other words, a Palestinian state would end the Israeli occupation of parts of Palestinian territory but do little else for Palestinians—and they know it. Finally, Palestinian nationalism still seems to be more about destroying the Jewish state than about building a Palestinian one. That is why Palestinian leaders have said no to every partition effort and peace proposal.

Moreover, at least until Iran has a government that seeks peace in the region rather than Israel’s destruction, a sovereign and independent Palestine would represent yet another route through which Iran would seek to attack Israel. The region has seen this movie before with Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza, and the only thing that has prevented the same disaster in the West Bank has been the constant intervention of Israeli forces. (Palestinian security forces have often worked with the Israelis against Hamas, which is the rival of the West Bank’s ruling Fatah party. But those forces are simply not strong enough to defeat Hamas alone, even if they wished to do so). Today’s Israeli police and military presence in the West Bank would be impossible in a newly sovereign Palestine, and Israeli interventions there to prevent Iranian or Hamas activities could be seen as acts of war that would violate Palestine’s internationally recognized borders.

Polls make it clear that both Israelis and Palestinians are highly unenthusiastic about a two-state solution.

That leaves only one genuinely viable long-term arrangement that would allow Israel to safeguard its security and let Palestinians enjoy normal lives free from Israeli rule: confederation. The separation of Israelis and Palestinians into two entities was the right idea when the British first proposed it in the 1930s, when the UN called for it in the 1940s, and when the United States began to seek it in the 1970s. And it remains right. The question is the nature of the Palestinian entity. The most sensible idea would be to create a Palestinian government that would join a confederation with an existing state, one that already has a stable and effective security force, maintains law and order, and fights terrorism; a currency and a central bank; and a secure international airport and other aspects of sovereignty. There is one clear candidate: Jordan, which borders the West Bank and whose population is overwhelmingly Muslim, Arabic-speaking, and already half Palestinian. The model to think of is Iraqi Kurdistan: an entity within a state, with a good deal of authority over local affairs. The Reagan administration envisioned something like that in the peace plan it put forward in 1982, which called for “self-government by the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza in association with Jordan.”

If the goal is normal lives for Palestinians and security for Israelis, a Palestinian-Jordanian confederation is preferable to the impossible dream of a well-governed, peaceful, democratic Palestine that poses no threat to any of its neighbors.

The scale and brutality of the October 7 Hamas attack shook Israel and raised questions about its military competence and ability to defend itself against implacable enemies. That attack has now been followed by last weekend’s mammoth Iranian aerial assault, in which the Islamic Republic deployed hundreds of drones and rockets against Israel.

Israelis understand that their country’s long-term survival depends on reasserting deterrence by striking back: displaying resilience, determination, and military prowess. A decision about Iran lies before them, but the decision on Gaza was made last fall and looks even more correct today than it did at the time. Israel must end Hamas’s rule in Gaza and eliminate the group’s ability to attack Israel, both to protect the country and to put its other enemies on notice that killing Israelis will elicit a crushing response. Iran has sought to turn its “axis of resistance” into a ring of fire around Israel. Israel is rightly determined to put that fire out.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News