Kamran Bokhari, senior director of Eurasian Security and Prosperity at the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy in Washington, in his recent piece entitled “Kazakhstan and U.S. Strategy” and published by The National Interest, said: “Central Asia, a vast land-locked area between Russia and China, deserves far more U.S. attention than it currently gets. Greater U.S. engagement with the region can help counter Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Similarly, U.S. efforts to compete with China can get a boost given that this region is critical for Chinese geo-economic prowess. At the same time, having a robust relationship with the heart of Eurasia will allow America to create a pressure point for Iran, which is aggressively trying to alter the security architecture of the Middle East. Furthermore, it will enable the United States to ensure that Taliban-run Afghanistan does not become a haven for transnational jihadist agendas at a time when the Islamic State is on the rise again”.

The author’s estimation of an American would-be strategy for the Central Asian region appears quite realistic. The only question that appears to remain unanswered in his piece is the following: what would be the concrete path of moving forward to accomplish the noted objectives? This is just where a hitch is when it is a question of really challenging Russia’s traditional clout and China’s rapidly growing influence in Central Asia. After all, if one power intends to create a pressure point in a region or a country, located in the rear of its two most significant power rivals, it has to have reliable access to them. That is the very thing it should get first to ensure the delivery of what that region or country seeks from it and what it can offer them. But there is a problem with that in the present case.

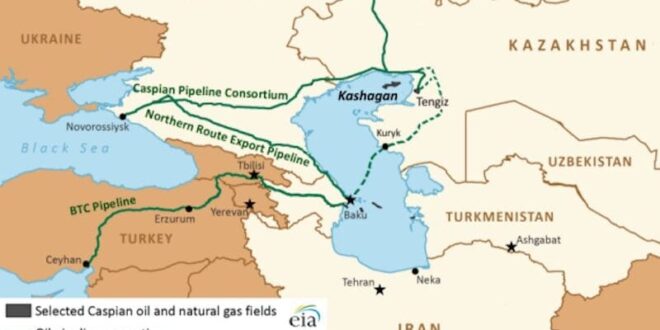

Central Asia including Kazakhstan is inaccessible to the West, except through Azerbaijan and the Caspian Sea. Its other surrounding countries – Russia, China, Afghanistan, and Iran – can hardly be called Western-friendly. The situation gets worsened by the fact that the waterway through the Caspian from Central Asia to the South Caucasus and vice-versa may also be seen as being controlled by Russia, as the Russian Caspian Flotilla is the largest and most powerful naval group in the Caspian Sea basin. That is hampering or even blocking Central Asia’s accessibility for the USA and its allies through Azerbaijan and the Caspian Sea is quite within Russia’s power in the worst scenarios.

It cannot be said that the West did not try to lead Central Asia out of control of Russia in terms of logistics. In the later stages of the Western coalition’s stay in Afghanistan, there were efforts made by Washington to create conditions for establishing economic and trade ties bypassing Russia, China, and Iran that would connect the post-Soviet Central Asian region to the markets in South Asia and beyond. Before the summer of 2021, such plans were repeatedly discussed during the meetings within the framework of the C5+1 format. The New Delhi Times, in an article by Himanshu Sharma entitled “US to link South & Central Asia” (July 20, 2020), said: “The United States and five Central Asian countries pledged to “build economic and trade ties that would connect Central Asia to markets in South Asia and Europe”. Their joint statement in Washington in mid-July called for a peaceful resolution of the Afghan situation for greater economic integration of the South and Central Asian regions”. Among other things, they included a project for building railway links between [post-Soviet] Central Asia and Pakistan.

Now, the latter seems to be getting more concrete. Kazakh Deputy Prime Minister Serik Zhumangarin, while having a meeting with Taliban officials in Afghanistan on April 24, stated that Kazakhstan was interested in participating in the construction of the Trans-Afghan Railway project. The interesting point here is that Russia expressed interest in the same thing even earlier. The Russian Federation is ready to take on part of the financing of the work and the preparation of a feasibility study of the project. It is claimed that Russia, which is now under sanctions restrictions, is interested in developing a new transport corridor since it gives it additional access to the world’s oceans. The above reports would seem to indicate that the eastern route of the North-South Corridor, a planned railway route that is meant to connect Russia to the Indian Ocean via Central Asia and Afghanistan, is gaining relevance in Moscow’s international agenda. That is, it can be assumed that the Russian side plans to control that route in one way or another, once it becomes operational. This seems to be, by no means, what Washington and its allies wanted for Central Asia to be done.

It means that in terms of independent access to Central Asia, the US and its allies still have no choice but to continue to count on the trans-Caspian direction. In that context, all further plans for the development of transport and logistics between the West and Central Asia without involving Russia and, to a lesser extent, Iran, find themselves linked to the Caspian Sea ports of Aktau and Kuryk in the Mangystau province, located in the south of Western Kazakhstan. Of all the countries in the region, only Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have access to the Caspian Sea. The port of Turkmenbashi in Turkmenistan is much closer to the port of Baku in Azerbaijan and much farther away from Russian territorial waters, than Aktau and Kuryk. Yet it seems doubtful that Turkmenistan which pursues a policy of neutrality, can be involved in the actions related to the great powers rivalry in the Central Asian region. As regards the formal position, the Turkmen officials have never expressed positions regarding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But informally, they have been and are being seen as more inclined towards supporting Russia over the West. According to Azattyq, in Turkmenistan, “officials have carried out pro-Kremlin propaganda efforts, blaming the West for provoking the war in Ukraine and warning against foreign ‘agents’ who are allegedly trying to destabilize the country”. Turkmenistan’s representative to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), Khemra Amannazarov, left the conference room during the speech of Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmitry Kuleba at a meeting of the OSCE Council of Ministers on December 1, 2022. He returned after the latter had finished his speech.

No Kazakh official would afford things like that. Astana’s representatives try to behave utterly correctly towards both the West and Russia. The result is that both in Russia and the West, there are often those who suspect Kazakhstan of playing a double game. Kazakhstan has faced repeated accusations by opponents of Putin of helping Russia obtain sanctioned goods that can be used to aid Moscow’s war effort in Ukraine despite Astana’s vows to avoid helping Moscow circumvent Western economic penalties. Symmetrically, there have been accusations by supporters of Putin toward the Central Asian nation of assisting activities of the West against Russia. There is no point in giving examples – there are a lot of them. To tell the truth, the current system of relations within the triangle of Russia – Kazakhstan – the USA, and its allies seems to suit the Russian leadership just fine. The Kremlin’s propagandists continue – largely because of inertia – to blame the Kazakh ruling regime for many alleged sins against Russia.

But at times some of them start revealing things. Thus, just recently, one of the mouthpieces of Russian state propaganda has publicly claimed that “Tokayev is a product of Moscow” and “the fact that Kazakhstan, at the very least, helps Russia bypass sanctions is, I repeat, not the country’s State policy, but Tokayev’s personal merit. If he leaves, all this will be over”.

Hence the conclusion suggests that the Kremlin is not too worried about the Kazakh regime’s alleged flirting with the West. There does not yet appear to be a substantial change in relations within the triangle of Russia – Kazakhstan – the USA, and its allies. Even if there is any, it is most likely not in favor of the West. The Kremlin seems to be aware that it still takes the upper hand in relations within that triangle. The only thing that can worry it in this regard is any possible attempts by the West to gain a foothold on the Kazakhstani coast of the Caspian Sea – in the ports of Aktau and Kuryk. It can be assumed that in the event of the slightest suspicion on this account, the Russian Federation, as the former head of the National Security Committee of Kazakhstan, Alnur Musayev noted, may “attack Kazakhstan to cut off the Central Asian nation from the Caspian Sea – from Astrakhan [a city in the Russian Federation] to Aktau [a city in Kazakhstan] and to the border with Turkmenistan”.

It’s an entirely different story when it comes to relations within the triangle of Russia – Kazakhstan – China. In there, that is Beijing which is taking the upper hand, and Russia is losing its position. In this context, one news report appears to be worthy of special attention. This is the statement by the Kazakh Minister of Trade and Integration, Arman Shakkaliev, about China having come out on top among Kazakhstan’s trading partners, surpassing Russia.

In terms of trade with Kazakhstan, China, according to Chinese figures, for the first time bypassed Russia a decade and a half ago. According to the Kazakh statistical data, this first happened only in 2023. The discrepancies in Kazakhstan-China trade turnover value can perhaps be attributed to differences between the methods of keeping statistics. But, in truth, such an explanation sounds quite unconvincing, as the data of the parties varied and is still varying widely. For instance, China was Kazakhstan’s largest trade partner in 2023, with bilateral trade turnover reaching $41 billion, a 32% increase over the previous year’s total, according to Chinese figures. The Kazakhstan side, meanwhile, reported total bilateral trade in 2023 as totaling $31.5 billion, while the volume of trade between Kazakhstan and Russia amounted to $26 billion.

But anyway, one can talk about China starting to economically squeeze Russia out of Kazakhstan. Moscow can’t stop this, without being dragged into a direct conflict, as China shares a 1,783-kilometer border with Kazakhstan and does not need to turn to Russia’s logistical mediation. Central Asia remains the only region in the post-Soviet space where Russia still maintains a major influence. And if the Kremlin loses its significant clout over what happens in Kazakhstan, the rest of Central Asia will be mostly cut off from Russia, and Moscow will become dependent on Astana in developing its relationship with the other Central Asian countries. This seems to have to look like an even more alarming prospect.

Therefore, it is not surprising that some Russian military and political experts (topwar.ru) are beginning to say that “Russia and China now are in the run-up to the battle for Kazakhstan”.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News