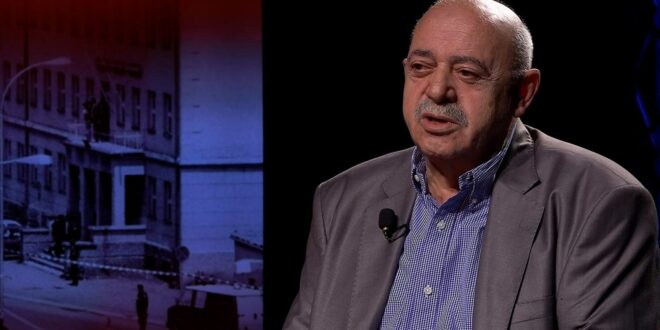

Ilaz Bylykbashi, a photojournalist from Kosovo who began work in the 1970s, recounts some of the historic events he captured on camera – including the aftermath of the 1998 massacre of Kosovo Liberation Army fighter Adem Jashari and 58 others.

“I had stayed in their Oda (a traditional room for hosting guests in Albanian households), filmed them playing football in the yard and, seven years later, I took photographs of them dead; it was difficult and heavy.”

Ilaz Bylykbashi, a photojournalist from Kosovo, was telling Kallxo Përnime of the moment he documented the massacre of Kosovo Liberation Army commander Adem Jashari and 58 others, including dozens of his relatives.

In March 1998, after they were killed by Serbian forces, Bylykbashi “photographed each body one by one”.

“I took over 500 photographs of this massacre in 45 minutes,” he recalls.

He adds that the then Mayor of Skënderaj, Xhafer Murtezaj, “saved” him. “When he saw I wanted to put the cameras in my bag, he told me: ‘Leave that, do not touch them, I will bring them tomorrow to Prishtina,’” Bylykbashi says.

Being caught “returning with cameras” would have risked serious consequences under the harsh Serbian regime in Kosovo.

The retrospective interview looked at Bylykbashi’s long career, photographing different events in Kosovo from the 1970s to the 1990s, including the massacre of Jashari and 58 others, the majority of whom were women and children, in the village of Prekaz in Skënderaj.

The mass murder took place seven years after Bylykbashi first met and photographed the family in November 1991, on the anniversary of the Trepça miners’ protest.

Serbian police first attacked the Jashari family home in December 1991. A second attack followed on January 22, 1998. The women and children of the family joined the resistance over the course of a 30-minute gun battle, but two of Jashari’s neices, Iliriana and Selvete, were wounded.

The third and final attack happened on March 5, 6 and 7 that year and proved fatal for 58 people in Prekaz. 22 of whom were close relatives of Jashari. Only two people survived the massacre. A family member, Besarta, saw every family member of hers die.

“When we took the photographs of the 58 bodies from the Jashari massacre, there were police forces in every corner. We no longer knew what fear was. I took up to seven different photographs of Commander Adem Jashari,” Bylykbashi says.

Relentless violence against journalists

Bylykbashi told BIRN that Kosovo Albanian journalists like him were violently mistreated in the 1990s by the Serbian regime. He recalls being beaten and threatened multiple times because of his work.

One historic photograph he took was of the moment when the sign “Rilindja” – name of the only publishing house in Kosovo printing in Albanian – was removed from the top of the building and replaced with “Gracanica”, written in Serbian Cyrillic letters.

That event took place soon after Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic scrapped Kosovo’s autonomy in 1989 and imposed a de-facto apartheid system.

According to Bylykbashi, the Serbian authorities wanted “to colonize everything, meaning that everything was now written in Cyrillic. Even names. ‘Rilindja’ (an Albanian term, written in Latin script) hurt their eyes,” he says.

Bylykbashi started working as a photojournalist at Bota e Re (New World) newspaper, then later for more than two decades for Rilindja newspaper, which the Milosevic regime closed in 1990.

As a fallback option, the journalists from the paper started writing the same information for Bujku (The Farmer), which was the only daily newspaper to survive in Albanian in Kosovo until the birth of Koha Ditore in 1997.

The Serbian regime did not close Bujku, according to Ilazi, as “it was useful for Serbia to get free information” on how Kosovo Albanians were organising their own parallel systems.

In 1992, he went to report on the first action of the Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, in which a Serbian police officer died. He and other journalists were beaten by the police.

“When we went there, the police had formed a cordon… when they saw that we were journalists they told us: ‘We’ve been waiting for you like a bird waiting for its prey’ and locked us up and beat us up. Two hours later, we were out, and, thank God, the cameras were untouched. We cleaned the blood from our face and bodies so our kids at home would not see us in that condition,” he remembers. “But I barely could walk for three months,” he adds.

The most fearful moment for him came when he and his family were threatened after an exhibition of his photographs opened in Tirana, Albania, in 1998.

“They [the authorities] found films of the exhibition I had in Tirana in 1998. They [Serbian police] undressed me and beat me at the border,” he said. “They said: ‘Your next exhibition will be of photographs of your dead family’. When they mentioned my family, fear filled me,” Bylykbashi says, adding that he moved his family from his original home for a while after that.

When he was expelled from Kosovo in 1999, Bylykbashi moved to Australia. I had to leave “with my sandals on… they took everything…even my cameras,” he says.

In Australia, he went to see a doctor, and he had his book with him so she knew what had happened to him. The doctor “had treated Bosnian migrants with similar traumas… and told me that it would take 30 years for my injuries to heal,” he recalls.

Coffin full of dead bodies

Bylykbashi photographed other important KLA commanders and political figures of the time, as well as many funerals that remain stuck in his mind.

Many activists who joined the peaceful resistance movement of the 1990s were Kosovo Albanian former political prisoners from the 1960s-1980s who had gone to jail for demanding that Kosovo either get republic status in former Yugoslavia or unite with Albania.

Bylykbashi was one of the few photographers working inside the courtrooms where these stitched-up political trials were taking place. In one trial, in 1984, he photographed Fehmi Lladrovci, who later became a famous KLA fighter and was filmed in a BBC interview.

Alongside his wife Xhevë Krasniqi-Lladrovci, who was also a guerilla fighter, Lladrovc died in April 1998, fighting Serbian forces.

Due to his political activity, Lladrovci had been sentenced to 10 years in prison from 1985 to 1995, after which he later joined the KLA.

“I didn’t know who he was when I photographed him in 1984. These trials were done to put pressure on people (to abandon their political demands)” he says, adding that he only understood who Lladrovci was two weeks before he was killed, when he met him in a field, covering the massacres in Drenica.

One of the hardest moments of Bykykbashi’s career came five years after photographing Lladrovci, when he opened a coffin in Suhareke.

It was full of dead Kosovo Albanian soldiers. “These soldiers had served in the former Yugoslav army and were returned dead to Kosovo in 1989-1990,” he says.

Bylykbashi dismisses the claim that they committed suicide. He recalls that, “over the coffin was written: “Do not dare to open”.

Fatmir Tafaj “is a name I cannot forget”, he says. “He was killed by a bullet that had come out of his back, his face was shattered. It was not suicide. Suicide takes one shot only, not two or three.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News