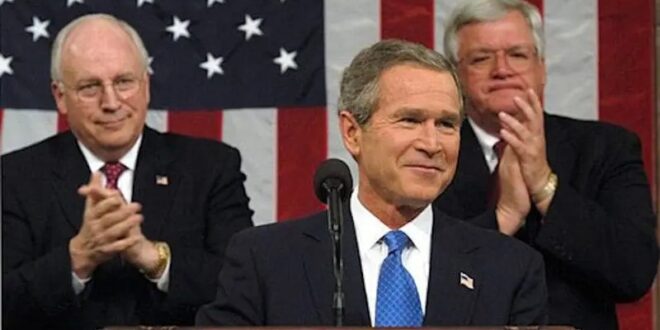

In 2001, after the horrific 9/11 attacks, an apoplectic George W. Bush administration ignored Congress’s narrow authorization to use military force against the perpetrators of the attacks and those who harbored them. Instead, it launched a grandiose global war on terror much broader than those wisely limited legislative instructions. Congress’s authorization attempted to restrict U.S. retaliation to the al Qaeda group sheltering in Afghanistan and their Taliban hosts then ruling that country. Instead, President Bush proclaimed a wider war on terrorist groups having “global reach.”

Bush took advantage of the American public’s blind outrage over the 9/11 attacks on U.S. soil and its ignorance that all Islamist groups, and even some rulers of Muslim countries, were not somehow implicated in the terror strikes on two American cities. Instead of using surgical raids and strikes to decapitate al Qaeda and Taliban leaders in Afghanistan, Bush ignored the failures of the British (in the late 1800s and early 1900s) and the Soviets (in the 1980s) in the “graveyard of empires” by ordering an invasion of that country to topple the Taliban and stand up a working democracy there. This two decades–long nation-building attempt to bring democracy to a country that wasn’t developmentally ready for it yet cost 243,000 lives and $2.3 trillion and ended in failure—with a resurgent Taliban reinstituting its oppressive rule.

Osama bin Laden, al Qaeda’s main leader, was not killed until 2011 by Bush’s successor, Barack Obama, because, despite the U.S. counterinsurgency quagmire in Afghanistan, Bush soon transferred many key intelligence and military resources to his higher priority invasion of Iraq. Falsely linking Iraq’s ruler Saddam Hussein to the 9/11 attacks, he involved the U.S. military in a costly, long counterinsurgency against Sunni guerrillas, which arose to fight the foreign invaders after Saddam had been toppled. One of these Sunni groups, al Qaeda in Iraq, morphed into the terrorist group Islamic State, or ISIS, which eventually took over vast swaths of land in Syria and Iraq.

Bush also conducted indiscriminate brushfire wars on many other Islamist groups in countless other countries, without regard to whether the groups posed an actual threat to the United States or were motivated by local grievances. In so doing, Bush was merely doubling down on the reason bin Laden had attacked the United States in the first place—excessive U.S. meddling in Islamic countries. Finally, Bush’s over-the-top war on terror also involved illegal surveillance within the United States, jailing suspected terrorist detainees without charges and the legal means to challenge their detention, the use of illegal torture on them, and the use of questionable kangaroo military commissions to try them instead of constitutionally guaranteed civilian trials.

But the war on terror didn’t end when Bush left office. Obama continued all these wars and started his own; his successor, Donald Trump, amped them up further. After seeing and inheriting Bush’s foibles in Afghanistan and Iraq, in a move that proved as disastrous as Bush’s invasion of the latter country, Obama took advantage of the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 to help eliminate the Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, a previous thorn in America’s side who had been playing ball with the West for some years.

Predictably, when popping the top off an iron-fisted dictatorship that holds a fractious country together, civil war and chaos were likely to ensue—and they did so in Libya as it did in Iraq. In fact, the rise of Islamist groups in the African Sahel, a semi-arid region south of the Sahara Desert, began when Mali fighters, who had defended Gaddafi, returned home to begin a rebellion with the plethora of weapon stocks from the late Libyan leader. Taking advantage of the turmoil, Islamist groups began to take over cities. A foreign intervention by the French pulled in other Western countries, including the United States, and expanded to other nearby West African countries in search of Islamists. Learning nothing from Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, France and the United States worked with governments perceived locally as corrupt.

This corruption was the kiss of death for the counterterrorism and counterinsurgency campaign that the French and Americans were prosecuting in the West African Sahel. Unlike conventional war between mass armies, as in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the success of such irregular wars, when it can be had, revolves around good governance rather than military suppression of the terrorists or guerrillas. In other words, these irregular forces usually have local grievances with particular governments. And in those brushfire wars, foreign intervention to help the corrupt governments further inflames the jihadists, as has happened as the Islamist rebellion spread against other American or French client states in West Africa. Despite the insertion of American and French troops and hundreds of millions of dollars in military aid, these foreign interventions have failed. Military coups in several Sahel countries (some perpetrated with the help of American-trained local forces) have expelled French and American forces, and al Qaeda and ISIS are resurgent against these new military juntas.

Governments, especially the U.S. superpower, never seem to learn. Instead of admitting that democracy cannot be exported using military force to countries not yet ready developmentally to generate the middle class and political norms for it to arise organically, the U.S. government is merely shifting its nation building projects to countries on the coast of West Africa. The Biden administration is naively offering these coastal nations a 10-year plan to build solar-powered security lighting and new police stations to help nix terrorism.

Of course, the larger issue is that U.S. officials admit that local grievances are fueling the insurgencies rather than Islamist ideology. Thus, even experts say that nation-building approaches, such as water or electrification projects, face daunting odds of succeeding. Moreover, identifying a threat to the United States by these local Islamist groups is difficult. The Chinese may be after minerals and the Russians may be trying to replace the U.S. and France to gain influence, but their efforts are likely to be as much a waste of time and money as that of the United States.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News