Key Takeaway: Tuareg insurgents with likely ties to the Tuareg separatist rebel coalition and al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate repelled a Malian-Russian offensive in northern Mali in the deadliest engagement for Russian forces since they arrived in Mali in 2021. The heavy casualties likely have prompted Malian and Russian forces to reconsider how, or if, they can address significant internal challenges to reestablish government control along the border. Russia is highly unlikely to decrease its presence in Mali despite the losses because of the Kremlin’s strategic interests in Mali and the wider Sahel.

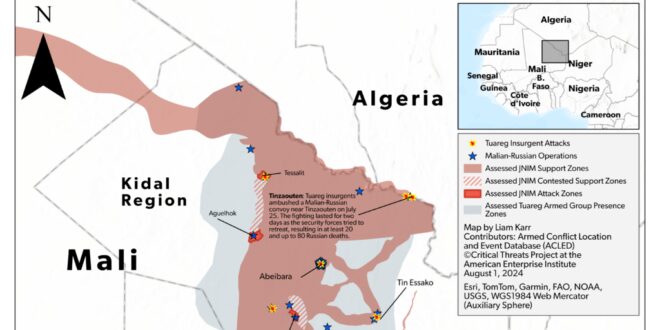

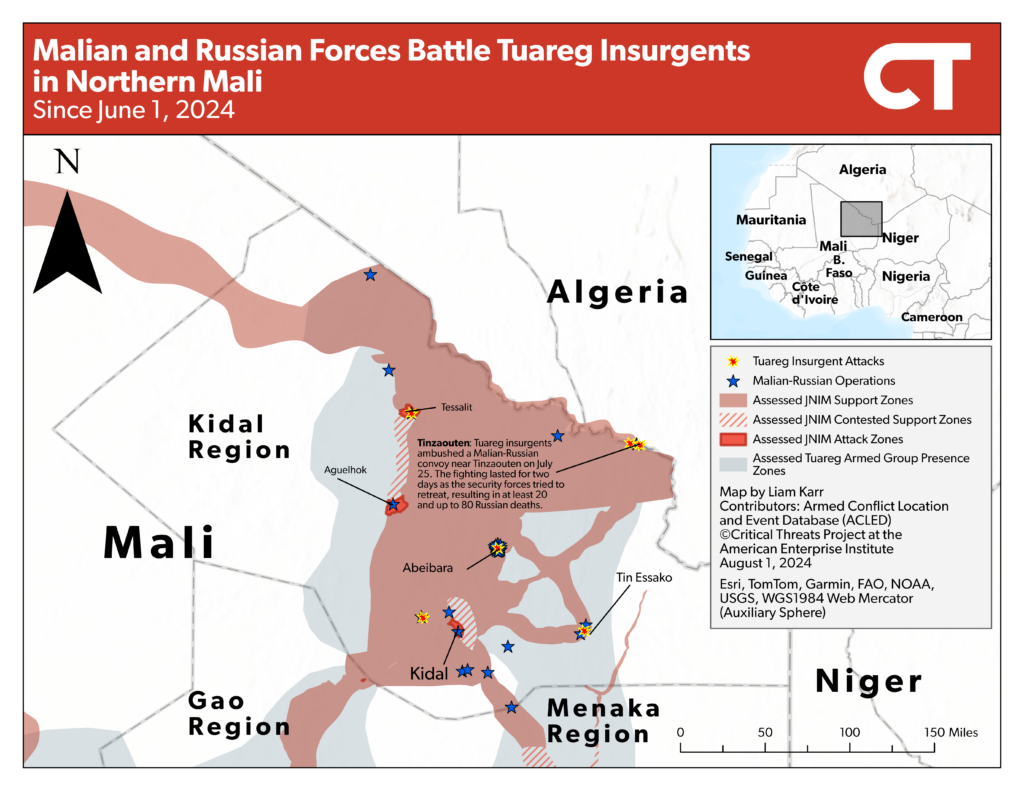

Tuareg insurgents repelled a Malian-Russian offensive in northern Mali in the deadliest engagement for Russian forces since they arrived in Mali in 2021. Since late June, the Malian army and its Russian auxiliaries have been waging an offensive to clear Tuareg insurgents from remote areas of northern Mali’s Kidal region outside the government-held regional capital, Kidal city. Security forces spent late June and early July conducting operations around Abeibara, a strategically located town between Kidal city and the Algerian border.[1] The Malian junta has repeatedly emphasized that defeating the Tuareg insurgents and reestablishing government control in northern Mali is a leading priority and crucial tenet of national sovereignty.[2] Malian and Russian forces have repeatedly carried out atrocities against civilians as part of these operations.[3]

Security forces then extended their efforts into two separate areas in mid-July, the Tin Essako district, east of Kidal, and the Algerian border area.[4] The security forces lacked the capacity to hold positions along the border, so their convoys patrolled areas for a few hours before withdrawing to their bases farther south, allowing the militants to reenter the area.[5] Malian and Russian forces previously took control of forward operating bases to help hold newly contested positions during their initial offensive into northern Mali to capture Kidal, in late 2023.[6]

Tuareg insurgents near the Algerian border repeatedly withdrew before the arrival of security forces and avoided engaging them until July 25, near the border town Tinzaouten. A Malian-Russian convoy intended to capture the town’s vacant military base, presumably to set up a forward operating base as they did during their Kidal offensive in 2023 that would have helped sustain a more lasting presence along the border .[7] The fighting near Tinzaouten lasted several days and resulted in significant Russian casualties after militants halted the convoy south of Tinzaouten on day one and forced security forces to retreat into a deadly ambush the following day, which caused most of the casualties.[8] Russian insider sources reported that at least 20 Russian fighters died and that there were up to 80 Russian fatalities, including prominent commanders and military commentators.[9] The Malian army initially said it had lost two soldiers and a helicopter but acknowledged a “significant number” of losses on July 29.[10]

Figure 1. Malian and Russian Forces Battle Tuareg Insurgents in Northern Mali

Note: B. Faso is Burkina Faso.

Source: Liam Karr; ACLED.

Fighters with ties to the Tuareg separatist rebel coalition and the al Qaeda–linked JNIM were almost certainly involved in the attack. Both groups claimed the attack. The Permanent Strategic Framework for Peace, Security, and Development (CSP-PSD) said on July 28 that its fighters had routed the convoy and captured a significant amount of materiel and prisoners.[11] Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) put out its own statement with photos of loot on July 28 saying its fighters had ambushed the convoy south of Tinzaouten and killed at least 50 soldiers.[12] CSP-PSD has since denied JNIM involvement and accused JNIM of trying to steal credit for the attack.[13] The Associated Press and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported that both accounts are mostly accurate and that the original CSP-PSD attack forced security forces out of the town and into the area where JNIM ambushed the convoy.[14]

The Tuareg separatist coalition has significant historical ties to JNIM. The factions’ leaders have relationships dating back to at least the 1990s.[15] An al Qaeda–linked Tuareg group that is now a JNIM subgroup initially fought alongside the Tuareg separatist rebels during the 2012 Tuareg rebellion.[16] However, the Salafi-jihadi militants sidelined the more secularist rebels and expanded their offensive into central Mali, which prompted the French military intervention in 2013 and helped formally split the separatist rebels from the al Qaeda–linked insurgents with a 2015 peace agreement.[17] The groups have still kept in contact in subsequent years, made informal ceasefire agreements in their shared support areas, maintained significant areas of operation and membership overlap, and operationally coordinated against the Islamic State Sahel Province since 2021.[18]

Connections between the two sides have likely strengthened since Malian and Russian forces began attacking the separatist rebels in northern Mali in 2023 following the withdrawal of UN peacekeepers. The Malian junta expelled the UN forces in 2023.[19] The UN forces had facilitated crucial reconciliation efforts that were part of the 2015 peace deal between the junta and non-jihadist rebel groups.[20] The junta also attacked the rebel factions for the first time since the peace agreement went into effect, as both groups tried to backfill the withdrawing UN forces in 2023 and scrapped the peace deal at the beginning of 2024, signaling their intentions to resume hostilities with the rebels.[21] JNIM took advantage of this development to repeatedly offer to ally with separatist groups and northern communities in the Kidal region against their mutual enemies: the Malian army and the Russian auxiliaries.[22]

The two factions are almost certainly at least deconflicting their activity to channel their efforts against Malian forces and their Russian auxiliaries. CTP assessed in October 2023 that the two groups were at least tacitly enabling each other to operate in shared areas and may explicitly be coordinating some attacks based on the close timing and proximity of their attacks against security forces operating in northern Mali, much like the Tinzaouten ambush.[23] The UN and French media reported in 2024 that the CSP-PSD and JNIM are interested in establishing a formal nonaggression pact to coordinate their activity, but they have not reached an agreement.[24] The proposed pact aims to protect the free movement of fighters and facilitate information-sharing but explicitly rules out combined attacks. Outright cooperation would create legitimacy issues for both sides, given their tumultuous history and differing end goals due to the CSP-PSD’s secularism and JNIM’s Salafi-jihadi ideology.[25]

The Algerian border area has also served as an important rear support zone for JNIM and the Tuareg separatists for over a decade. Separatist rebels have controlled Tinzaouten since they captured it in 2012 alongside the al Qaeda–linked militants.[26] The separatist rebels control artisanal gold mines in the area, although local sources and experts say JNIM likely also gets a portion of the revenue due to its presence in the area and ties to the rebels.[27] Security forces killed high-ranking JNIM leaders headquartered in the area as recently as 2018, and French media reported in 2023 that the JNIM emir might reside in the area with the help of Algerian interlocutors.[28] Independent sources reported that the CSP-PSD head led the CSP-PSD ambush, while Russian sources claimed that high-ranking JNIM leaders were also involved in the JNIM attack.[29]

Ukraine claimed to provide “information” to the attackers, but the insurgents already possessed the capability and likely the intelligence to carry out the attack. The spokesperson for Ukraine’s military intelligence agency said that “the rebels received necessary information, and not just information” to enable the successful attack.[30] The BBC debunked a doctored image published by Ukrainian media that claimed to show rebels holding a Ukrainian flag after the attack.[31] The insurgents also possessed the capability for this severe of an attack without any external assistance. The militants have long-standing support zones and knowledge in the region, presumably knew where security forces were moving given their highly visible activity along the border area over the prior week, benefited from favorable weather conditions that trapped security forces and degraded their air support, and had substantial numerical superiority over the security forces.[32]

The heavy casualties likely have prompted Malian and Russian forces to reconsider how, or if, they can address significant capacity and capability challenges to reestablish government control and degrade insurgent support zones in northern Mali. The Malian army said on July 29 that the setback “cannot call into question” its efforts to bring all Malian territory under government control, indicating that it remains a high-priority item for the junta.[33] However, the army did acknowledge that it would analyze the battle to learn lessons and adjust its security and stabilization strategy.[34] A prominent military commentator linked to Russian veterans also called for Russian forces to learn from the incident.[35]

Malian and Russian forces face several capacity issues that limit their ability to operate across northern Mali. The forces sent to capture Tinzaouten were overstretched, making them an easy target for the insurgents. The convoy sent to capture the town initially consisted of only 12 vehicles.[36] The convoy radioed for reinforcements, but Russian sources claimed that they received “extremely limited” help, amounting to a maximum of 70 additional soldiers.[37] Russian sources claimed that this small contingent faced an overwhelming force of over 1,000 insurgents.[38] Even if the Russian claims are exaggerated, the small force was too small to contest a well-established insurgent support area. The other convoys patrolling the Algerian border faced the same capacity issues and were not targets of a massive ambush.[39]

The security forces are also heavily reliant on air support, which contributed to their defeat at Tinzaouten. The Malian and Russian official accounts of the attack separately attributed the defeat to a sandstorm that halted the convoy and prevented air support from intervening in the initial battle near Tinzaouten before they retreated into the deadlier ambush.[40] Drone support had previously driven the separatist rebels from the military base in Tinzaouten in December 2023 and contributed to the successful Malian-Russian offensive in northern Mali in late 2023.[41] Air support degrades insurgents’ abilities to carry out effective ambushes by targeting massed forces with drone strikes and reporting massed forces to vulnerable security forces. Security forces have already carried out multiple air strikes around Tinzouaten since the ambush.[42]

Russian forces are pivotal to the junta’s efforts to reassert itself in northern Mali but likely lack the capacity to address their already existing shortcomings or sustain such high casualties without drawing on forces from other areas of Mali.[43] Russian forces were essential to the capture of other longtime rebel strongholds in northern Mali in late 2023.[44] The casualty disparity between Russian and Malian forces at Tinzaouten indicates that Russian soldiers made up the bulk of the offensive forces and remain indispensable to the Malian government’s efforts in northern Mali. However, Russia is already facing capacity limitations across the continent due to the Kremlin redeploying unspecified units to Ukraine and struggling to meet its recruiting goals.[45] CTP previously reported during the late 2023 offensive against Kidal that this decreased Malian-Russian operations in central Mali.[46] A similar pattern would risk JNIM making significant gains in more populated and politically important areas of central Mali, which the UN reported JNIM has already prioritized over northern Mali in 2024.[47]

Insurgent rear support zones along the border with Algeria further challenge Malian and Russian soldiers’ ability to degrade insurgent capabilities along the border. Tuareg rebels retreated to the border when security forces began their patrols in July before returning to the targeted areas after security forces withdrew.[48] Algeria is unlikely to cooperate with Mali, which enables the insurgents to take advantage of the porous border to outlast and outmaneuver security forces. Algeria strongly supported the 2015 peace agreement and attempted to salvage the deal in December 2023 due to fears that renewed hostilities in Mali would mobilize the Tuareg population in Algeria and cause refugees to flee into Algeria.[49] Mali withdrew its ambassador from Algeria in retaliation for those efforts. Algeria also relayed its fears of the Wagner Group’s destabilizing impact to Moscow in May 2024, presumably referring to Russia’s role in the renewed conflict in northern Mali.[50]

Russia is highly unlikely to decrease its presence in Mali despite the losses because of the Kremlin’s strategic interests in Mali and the wider Sahel. Russian forces under the Wagner Group banner have also been active in other theaters where they faced significant casualties, such as Libya, Mozambique, and Syria. Wagner was active in Mozambique for less than a year before it withdrew in late 2019 after sustaining dozens of casualties against IS-linked insurgents.[51] Russia had only business interests in Mozambique, and Mozambique had other partners willing to take Wagner’s place.[52] However, Russia maintained its presence to varying degrees in Libya and Syria due to the Kremlin’s strategic interests in both countries and those regimes’ reliance on Russian support.[53]

Mali is a vital piece in the Kremlin’s strategic ambitions in Africa to supplant the West and better position itself for prolonged confrontation with the West, making Mali more like Libya or Syria than Mozambique. The Kremlin has deployed nearly 2,000 soldiers to Mali to help the Malian junta fight the Salafi-jihadi insurgency and Tuareg rebels since 2021 as part of its efforts to expand its military footprint and degrade and deny Western access to the continent by targeting the West’s overreliance on France and security partnerships.[54] This initial security sector partnership opened the door for greater economic cooperation, which aims to mitigate the financial impact of tensions with the West by exploiting new revenue streams and export markets. The Malian and Russian governments have signed several cooperation agreements on oil, gas, uranium, and lithium production since March 2024.[55]

Mali is also a crucial partner for Russia’s broader political project in the Sahel. Mali is part of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) with the pro-Russian juntas in neighboring Burkina Faso and Niger. The AES advances Russia’s political objectives of creating a bloc of political allies that help offset Western isolation in international forums and advance Russian information narratives.[56] The AES agreed to establish a formal confederation on July 6, 2024, which expands the AES’s operational scope from a mutual defense agreement to a body that intentionally coordinates various policies, further increasing its use as a coordination tool for Russia.[57]

Mali is a key facilitator for Russian engagement with the rest of the Sahelian alliance. Mali had already directly facilitated cooperation between Russia and the rest of the AES by hosting meetings between Russian officials and their Burkinabe and Nigerien counterparts and serving as a base area for Russian officials to travel to the neighboring AES countries.[58] These efforts helped Russia solidify its position as a growing economic and military partner for the other alliance members.[59] The junta leaders agreed that Malian junta leader Assimi Goita would be the first holder of the yearlong confederation presidency, further solidifying Mali’s role as a crucial interlocutor.[60]

Prominent Russian military commentators have said that the Russian Ministry of Defense (MOD) could use the incident to replace Wagner fighters with Africa Corps recruits to further consolidate its control over the continued Russian presence in Mali.[61] The MOD created the Africa Corps to formally take over the Wagner Group’s operations in Mali in late 2023 as part of its efforts to subsume Wagner’s global portfolio following the death of Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin, in August 2023.[62] Russian MOD personnel already heavily supported Wagner’s activity Mali before the creation of Africa Corps, meaning there was little tangible change for Russian forces in the country.[63] Wagner’s leadership remained intact, there was no noticeable change to the group’s objectives or operations, and Wagner fighters kept their uniforms and traditions if they signed a contract with the MOD.[64] Russia also maintained Wagner Group branding as part of its operations in Mali to keep a thin veneer of plausible deniability.[65] This move has given the Malian junta the confidence to keep lying about the presence of Russian forces in Mali, and it enables Russia to frame blunders like the Tinzaouten ambush as a Wagner defeat instead of a Russian defeat.[66]

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News