The China Shock Is Over—and More Tariffs Will Not Help Workers

Kamala Harris and Donald Trump have profoundly different visions for the future of the United States. They wildly diverge when it comes to social issues, such as abortion. They do not agree on whether to raise or cut taxes. And they could take U.S. foreign policy in opposing directions, especially when it comes to the country’s alliance with Europe.

Yet there is one issue on which the Democratic and Republican nominees are in sync: protectionism. Trump has proposed sweeping tariffs of 10–20 percent on the vast majority of goods. Harris has been more critical of across-the-board tariffs, but according to a campaign spokesperson, she would nonetheless “employ targeted and strategic tariffs to support American workers, strengthen our economy, and hold our adversaries accountable.”

This concurrence is not surprising. Over the past decade, protectionism has gained bipartisan support. During his four years in office, Trump slapped tariffs on imports from both allies and adversaries. President Joe Biden promised to usher in a different trade era, pledging a return to multilateralism. Yet the Biden administration maintained almost all of Trump’s tariffs, added new ones, and expanded “Buy American” provisions that mandate federal agencies purchase domestic products.

According to Biden, Harris, and Trump, such restrictions protect American industries from foreign competition. They argue that tariffs can promote national security, foster economic growth, and restore blue-collar jobs, which, they claim, have disappeared because of import competition. “I’m going to renegotiate our disastrous trade deals,” Trump said during his 2016 campaign. “We will only make great trade deals that put the American worker first. And we are going to put our miners and our steelworkers back to work.”

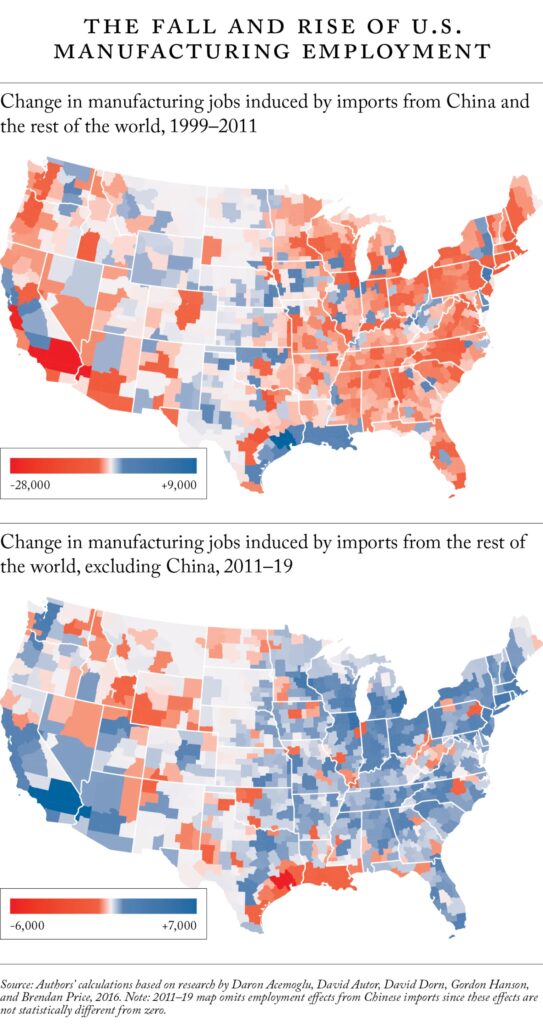

It is true that import competition, specifically from China, cost the United States manufacturing jobs. But politicians are wrong to suggest that protectionism will help generate employment. A new study we conducted using recent trade and employment data shows that Chinese import competition is no longer a factor driving U.S. manufacturing employment. The United States stopped shedding manufacturing jobs after the first decade of the twenty-first century—long before Washington began slapping levies on Chinese products. The share of American jobs in manufacturing remained steady even as Chinese imports to the United States continued to grow between 2011 and 2018. It has remained constant since, even as Trump applied tariffs and Chinese exports to America fell.

The United States, in other words, is fighting the last trade war. Its current policies are designed for a period that has long since passed, and they are not expanding the labor market. In fact, they may be suppressing employment. According to our research, trade with developing economies helps U.S. manufacturers hire more workers, largely by making it easier for these companies to import components.

Washington should, therefore, adopt a different strategy. Rather than pursuing protectionist policies, it should focus on reducing barriers and strengthening global economic ties. More important, it should prioritize finding ways to ensure that all Americans can benefit from globalization. Doing so is the best way to help workers in the United States—and across the world.

MISSING THE BOAT

Beginning in the 1990s, the U.S. manufacturing sector experienced substantial competition from China. The country’s spectacular investment in export-led economic growth and comparatively low wages made it much harder for low-skill U.S. manufacturing industries to compete in global and domestic markets. As a result, many companies shuttered factories and laid off workers.

These job losses were significant. According to research by the economists Robert Feenstra, Hong Ma, and Yuan Xu, the fast growth of Chinese imports resulted in about 1.5 million job losses in the United States between 1991 and 2011. In the regions with high concentrations of affected workers, poverty levels spiked, as did rates of addiction. Marriage and fertility rates went down. Many of these workers and their relatives turned to Trump, who promised to curtail trade with other countries and bring back employment. Their support helped him win the traditionally Democratic states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—and with them, the White House.

As president, Trump tried to make good on his promise. He slapped tariffs on China and Mexico. He began tolling imports from Canada and the European Union. The tariffs reduced imports, but U.S. exports also fell. More important, as a jobs-creation agenda, his tariffs failed. The “China shock,” it turns out, ended before Trump took office. Since then, imports from China have had no significant effect on U.S. employment. Trade with other countries, according to our research, never damaged the U.S. job market, either. The share of American jobs in manufacturing did not grow under Trump. Nor did it grow under his successor.

BOUNCING BACK

Tariffs have not resurrected American manufacturing. But they could suppress it. China contributes only 16.5 percent of total U.S. imports. The rest come from a combination of other countries, including several emerging economies—namely, Brazil, India, Mexico, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam. When our team looked at U.S. trade with these emerging markets, we found that imports have contributed positively to U.S. manufacturing employment. Between 2011 and 2019, imports from these economies created almost 500,000 American jobs, concentrated in many of the same regions that had lost jobs to China a decade prior. The reason for this growth is simple: the largest and most productive U.S. manufacturers tend to produce complex goods that have inputs sourced from other parts of the world. As a result, they have an easier time growing and hiring when imports are affordable.

Beyond creating a risk that U.S. exporters might face retaliatory duties, Washington’s fixation with tariffs diverts attention from the country’s strength in services. Business-services industries—such as software, engineering, R & D, and financial services—employ more than twice as many U.S. workers as the manufacturing sector at higher average wages. They provide millions of jobs to non-college-educated workers. Many of these industries are exporters, and American firms within them are global leaders. Yet many countries have high barriers to services trade, curtailing opportunities for Americans. Instead of raising tariffs on goods, U.S. policymakers should focus on reducing impediments to the services trade—which would help create more employment in the business service sector.

That trade helps create American jobs is good news for both U.S. workers and workers abroad who produce goods exported to the country. It means that everyone gains when the United States engages in global commerce. But it also means that proposals to apply tariffs, especially sweeping ones, as Trump announced, on U.S. imports could easily hurt both American and foreign workers.

Some scholars and officials who accept that tariffs have economic drawbacks still believe they are necessary for national security purposes. They argue that Washington must cut trade with China in particular, to avoid fueling Beijing’s rise and to make sure U.S. industries are never dependent on Chinese imports. But tariffs, like any other protectionist measure, are blunt instruments with which to address national security concerns. To reduce risks in supply chains critical to national security, American officials should instead pursue alternative policies clearly targeted at protecting national security while minimizing the economic costs.

The United States’ challenges lie not in globalization itself.

In fact, sweeping tariffs could make the United States less secure. If Washington applies broad and indiscriminate protectionist measures, countries might respond in kind. Such a trade war would be destabilizing. As many political scientists have shown, trade in goods and services helps foster peace by binding economies to one another, requiring that states adopt shared standards and practices, and necessitating cooperation between officials. Severing or weakening those ties would thus raise the risk of conflict.

None of this means that Biden, Harris, or Trump are wrong to worry about the struggles of U.S. workers and firms. Yet ultimately, the United States’ challenges lie not in globalization itself but in the fact that its benefits disproportionately flow to the well-off. Instead of withdrawing from the global economy, Washington should prioritize equipping its workforce with the skills needed to succeed in an increasingly interconnected world. They should pay particular attention to the training of non-college-educated workers, who often have more trouble finding employment. For example, the U.S. CHIPS and Science Act—the $280 billion bill passed in 2022 to boost American research and manufacturing—wisely expanded support for community colleges, vocational programs, and research institutions. Such policies are essential to equipping workers with jobs that allow them to be competitive in the global economy. At the same time, employers should emphasize hiring based on skills rather than pedigree. A college degree is not the only way to gain valuable skills. In fact, 51 percent of all workers in the United States have developed skills through alternative routes, such as training programs, the military, and community colleges.

Reactionary protectionism, by contrast, offers only temporary relief to struggling regions and industries. To build a resilient economy, Washington should instead pass more workforce and skills development measures like those found in the CHIPS and Science act. Doing so is the best way to upskill the U.S. workforce, promote the country’s economic interdependence, and position the United States for long-term success.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News