On 6 September, US media reported that Washington had confirmed that Iran had begun delivering several hundred close-range ballistic missiles to Russia for use against Ukraine, marking a new phase of the military collaboration between Moscow and Tehran.

Delivered at last

Initial claims of Iranian missile transfers to Russia surfaced in late 2022, shortly after Iran’s first shipment of uninhabited aerial vehicles (UAVs) to the country. At the time, US intelligence indicated that Iran was preparing to supply Fateh-110 and Zolfaghar short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs). Washington reiterated these concerns following then Russian defence minister Sergei Shoigu’s visit to Iran in September 2023, during which he viewed Iranian missiles. The following month saw the end of the UN’s missile-related restrictions on Iran, which had been imposed per UN Security Council Resolution 2231. While Iran continued to deliver Shahed UAVs and components to Russia – and North Korea began supplying Moscow with KN-23 SRBMs – Iranian missile transfers to Russia remained absent, fuelling speculation about delays or that Moscow or Tehran were having second thoughts.

In August 2024, Reuters reported that Russia had signed a contract in late 2023 for the purchase of hundreds of Iranian missiles. The same report indicated that, instead of the anticipated Fateh-110 and Zolfaghar systems, Iran would deliver Fath-360 and Ababil close-range ballistic missiles (CRBMs), with training on the latter having already commenced. In September 2024, the Wall Street Journal corroborated this claim, citing US government sources that confirmed Iran had commenced the delivery.

Less well-known than their longer-range counterparts, the Fath-360 and Ababil systems illustrate Iran’s recent focus on developing short-range tactical missiles adapted from larger, existing weapon designs. This activity may be motivated in part by Iran’s intervention in Syria, where operational experience revealed range gaps in its missile arsenal, which had been designed more for strategic deterrence than tactical warfare.

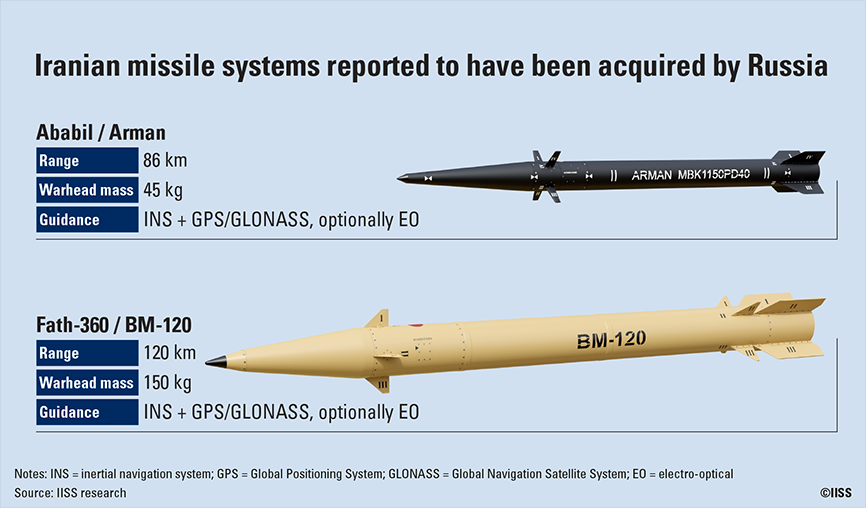

The Fath-360 (also known under its export designation BM-120) is a scaled-down version of Iran’s Fateh class of precision-guided solid-propellant missiles and has a range of 120 kilometres. Straddling the line between SRBMs and guided artillery rockets, the system can be launched from containerised multiple-launch platforms. Meanwhile, the Ababil (also referred to as the Arman) has a range of 86 km and carries a 45 kilogram warhead, making it broadly comparable – albeit lighter – to the United States’ GMLRS rounds. The Ababil has been extensively promoted for export, including at Russia’s Army 2024 exhibition, where it was displayed alongside a containerised six-unit launcher.

Both systems utilise inertial guidance in combination with GPS and GLONASS to achieve a reportedly high level of accuracy. The large antenna panels visible on both designs suggest the use of jamming-resistant controlled reception pattern receivers, which are already integrated into many of Iran’s UAV platforms. Jamming-resistant navigation systems would be particularly relevant in Ukraine’s heavily contested electromagnetic environment, which has previously degraded the combat effectiveness of US-provided GPS-guided systems. Both the Fath-360 and Ababil can also be fitted with electro-optical seekers; the electro-optical versions of these missiles may feature anti-ship capabilities.

Tactical and strategic implications

Though initial Western concerns focused on the potential use of the longer-range Fateh-110 and Zolfaghar missiles against critical infrastructure deep inside Ukraine, the shorter ranges of the Fath-360 and Ababil suggest that their employment will be more operational and tactical in nature. These systems would likely join existing Russian assets in similar range categories, such as glide bombs, extended-range Lancet loitering munitions, and guided rockets used by the Tornado-S multiple-launch rocket system (MLRS) in targeting high-value assets in Ukraine’s rear echelon.

While being primarily tactical systems in nature, Fath-360s and Ababils could have some strategic implications. Using shorter-range Iranian missiles for tactical strikes could free up Russia’s longer-range Iskander-M SRBMs for additional attacks against targets in Ukraine’s depth. The CRBMs could also be employed against Ukrainian population centres located closer to the front line and the Russian border, such as Kharkiv, Sumy, Mykolaiv and Zaporizhzhia.

While these Iranian missiles may not introduce a new capability to Russia’s war effort, they will offer increased flexibility and, most importantly, additional quantity. Iran has expanded its solid-propellant-production infrastructure in recent years and maintains robust supply chains for commercial off-the-shelf components, placing it in a strong position to fulfil large orders.

This purchase also highlights Russia’s continued inability to produce adequate quantities of comparable domestic systems, such as the Tornado-S, to meet its operational needs in Ukraine. A parallel might be drawn to Russia’s acquisition of North Korean KN-23 missiles, which offer no significant capability beyond that of Iskander missiles but add additional mass to the battlefield.

Beyond its immediate impact on the conflict in Ukraine, the missile transfer also signals a deepening of military ties between Russia and Iran. By supplying missiles to Russia, Tehran might be shifting towards more overt support of Moscow’s war effort, marking a departure from the more ambiguous stance it adopted following the delivery of Shahed UAVs in 2022. A key question is what other forms of military collaboration might emerge between the two states, and what Iran stands to gain in return for its missile support. Alongside much-needed financial and material compensation, Iran is reportedly seeking advanced Russian military capabilities, including fighter aircraft, combat helicopters, and air-defence systems, as well as access to Russian expertise and technology to enhance its domestic arms industry.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News