On September 27, the unimaginable happened. At approximately 5:22 p.m. local time, reports emerged of a massive Israeli strike on the predominantly Shia southern suburbs of Beirut, known colloquially as Dahiyeh. Six buildings had been flattened, throwing up pillars of thick reddish smoke against Beirut’s skyline, and an anchor with Hezbollah’s Al-Manar later said the Israeli explosives had “terraformed” the area. The first comments from the Israelis were uncharacteristically cryptic, even for them, about the strike’s target. But, clearly, it had been someone of high value, someone they wanted to ensure didn’t survive. Then the news started to trickle in on Hebrew media: Hezbollah’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah had been targeted, and the assessment was growing that he was killed.

Hezbollah’s media outlets, meanwhile, refused to deny Nasrallah’s presence at the strike’s location, exponentially increasing the likelihood of his death with each passing hour. Confirmation—from Hezbollah and Israel—would only come the next day on September 28. Nasrallah had died, leaving behind an organization virtually synonymous with his name.

Hassan Abdelkarim Nasrallah was Hezbollah’s third secretary-general, succeeding his predecessor, Abbas al-Musawi, to the post after Israel assassinated the latter on February 16, 1992. Nasrallah was born on August 31, 1960, either in east Beirut’s Burj Hammoud or, alternatively, in the south Lebanese village of Bazouriyeh—and grew up in the Lebanese capital’s poorer areas before the Lebanese Civil War, which began in 1975, forced his family to return to Bazouriyeh, their ancestral village in southern Lebanon. There, during his teenage years, Nasrallah became religiously and politically active with the Amal party before traveling to Najaf, Iraq, for higher religious studies. In Najaf, he met Musawi, who, at eighteen years Nasrallah’s senior, would ultimately become Nasrallah’s ideological mentor. Nasrallah returned to Lebanon in 1978, when Saddam Hussein’s regime expelled Lebanese Shia clerical students studying in Iraq, and rejoined Amal two years later, seeking to counter its increasingly secular direction under Nabih Berri, the successor to Amal’s founder Musa al-Sadr.

That effort lasted until one week after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, when Nasrallah and others defected to form Islamic Amal under the leadership of Hussein al-Musawi. With the Islamic Revolution Guard Corp’s (IRGC) guidance, in time, Islamic Amal would fuse with other similarly-oriented Shia Islamic groups to form Hezbollah.

Nasrallah spent most of the 1980s fighting in an embryonic Hezbollah’s ranks, resuming his religious studies, this time in Qom, in 1987. He returned to Lebanon two years later and joined the faction of Hezbollah opposed to an alliance with Syria. He traveled back to Tehran shortly thereafter, serving there as Hezbollah’s representative until he was recalled to Lebanon in 1991 upon Abbas al-Musawi’s appointment as secretary-general. Nasrallah was tapped to head the Executive Council—the body in charge of Hezbollah’s social activities.

In July 1993, Hezbollah’s Shura Council—its supreme consultative body—officially appointed Nasrallah as the party’s new secretary-general. The appointment was meant to be for a finite number of years and term-limited, but Nasrallah proved so successful and popular that the party repeatedly extended his position until it finally amended its by-laws to make his appointment permanent. From that point on, the person and the position became synonymous. During a conclave held between June and August of 2004, Nasrallah was additionally appointed as the head of the Jihad Council, Hezbollah’s supreme military body.

The Hezbollah over which Nasrallah assumed leadership in 1993 fundamentally differs from today’s Hezbollah. Unlike Hezbollah’s first chief of staff Imad Mughniyeh or Mughniyeh’s successor Mustafa Badreddine, Nasrallah was neither a brilliant military commander nor a philosopher-scholar like his future deputy, Naim Qassem. Nasrallah also lacked the necessary learning to be considered a great religious authority—but Nasrallah was a visionary and a capable guide for the nascent organization through some of its most formative periods and several historical inflection points.

As secretary-general, Nasrallah steered Hezbollah through Lebanon’s post-Civil War reconstitution, two major Israeli assaults in 1993 and 1996, Israel’s 2000 withdrawal from south Lebanon and the subsequent questions about the need for an independent “resistance,” America’s post-9/11 Global War on Terrorism and 2003 invasion of Iraq, Prime Minister Rafik Hariri’s assassination and Syria’s expulsion from Lebanon in 2005, a war with Israel in 2006, a decade-long civil war in Syria that threatened to depose Bashar al-Assad and eliminate a critical link for the Iran-led Resistance Axis, and then through the chaos of Lebanon’s post-2019 economic collapse—one of history’s worst financial crises. At almost every one of these junctures—and notwithstanding his post-2006 war “had I known” mea culpa—Nasrallah seemed possessed of a unique skill that guaranteed his organization’s survival and led it to further growth, aided as much by the incompetence or lack of will of his opponents as his brilliance.

The secretary-general oversaw not only Hezbollah’s transformation from a ragtag militia into perhaps the world’s most powerful terrorist army but also the expansion of its near-endless social arms—schools, charities, sports clubs, television stations—that made Hezbollah into a Lebanese social mainstay, its control over the country’s Shia community virtually uncontested. His decisions to maintain political integration, first into the Lebanese parliament and, after 2005, into its cabinet, made Hezbollah the country’s chief kingmaker. Unsurprisingly, the combination of these two factors earned Hezbollah the support of 356,112 of the country’s approximately 4 million eligible voters in the 2022 parliamentary elections—150,000 more than the second-largest party—and a 93 percent approval rating among Lebanese Shia earlier this year. And if the carrots do not suffice, Hezbollah has sufficient sticks to virtually nullify any effective opposition.

But even the greatest of chess masters are not infallible. From the standpoint of his partisan and personal interests, Nasrallah’s greatest mistake was to launch a war of attrition against Israel on October 8, 2023, transforming Lebanon into a “support front” for Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and Hezbollah’s other Gaza-based allies. That decision would ultimately prove fatal. Whether his mistake will also lead to the unraveling of the organization that he guided to the height of regional power remains to be seen. Still, his loss doubtlessly constitutes a monumental setback for Hezbollah and—given its position as the tip of the spear of Iranian regional expansionism—for the Resistance Axis writ large.

Not that Hezbollah lacks competent replacements—though who remains to succeed Nasrallah is unclear at the time of this writing, since twenty of the group’s senior most officials were with the late secretary-general at the time of his demise and the giant crater left in the ground by the Israeli bombs have made their bodies hard to identify. But Nasrallah was more than a competent leader: A veritable cult of personality was built up around him that made it hard to determine where the man ended and where the organization began.

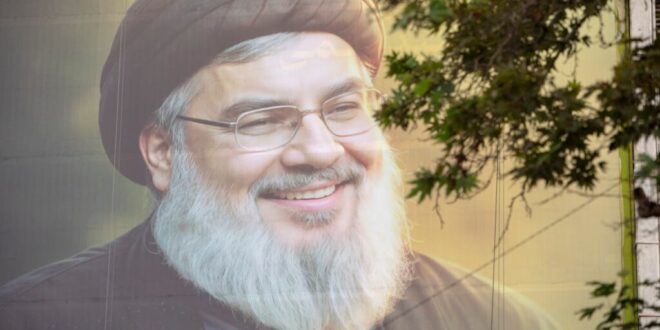

Everything from his alleged descent from the Prophet Mohammad to his name—meaning “Victory of God”—fed into this idolization and was deftly used by the organization to transform Nasrallah into an icon. His official biography even appears to have been embellished and streamlined to feed into this saintly image, at once imminent and familiar but also transcendent, with claims that, despite being from a non-observant family, he had become fully religious by age nine and was attending Velayat-e Faqih-oriented sermons by the age of ten—the ideal son. And somehow, sending his eldest son Hadi to die in battle against Israel on September 12, 1997, at the age of seventeen, while the elder Nasrallah remained safely behind also made him the perfect father. Songs about him abounded, both those created by the party and its faithful and those from non-Shia supporters—with at least one opera by famed Lebanese composer Ziyad al-Rahbani—some of which even flirted with Islamic sacrilege by likening Nasrallah to prophets.

Even as opponents mocked, his followers fawned—over his hand gestures, his turns of phrase, and even his speech defect when pronouncing the letter “R.” For an example of the cultish hold Nasrallah had on Hezbollah’s followers, one need only look to Press TV journalist Marwa Osman’s sudden and immediate breakdown on Russia Today upon learning of the group’s official announcement of his demise.

For Hezbollah, having a leader possessed of such mesmerizing magnetism over its flock certainly had its benefits. His routine speeches and periodic long-form interviews gave the party the opportunity to frame reality for its followers. Nasrallah’s various speeches and appearances also helped create and reinforce a Hezbollah worldview for the group’s support base—a framework into which all events and occurrences could be neatly fit. Setbacks could be explained away, even turned into victories. The group’s blemishes—its merciless slaughter of Syrians in support of a brutal dictator, its terrorism, its illicit and criminal activities such as the smuggling of Captagon—could all be spun, blunting any impact they may have on Hezbollah’s attraction for Lebanese Shia.

History, it seemed from Nasrallah’s speeches, was moving in a divinely preordained direction toward the victory of the group, its worldview, and the divine redemption of its followers. And Nasrallah’s word—the trust these followers misplaced in him—was the only proof needed.

But, by the nature of things, having a leader possessed of such charisma is a double-edged sword. For the secretary-general, like all men, was mortal, and whether his death had come naturally, of old age, or—as it did—by the hands of his mortal Israeli foes, Hassan Nasrallah was slated to go the way of the world. Now, whoever succeeds him must replace not only his administrative and organizational skills but a larger-than-life aura that the party designed. Hezbollah is doubtlessly possessed of a formidable organizational structure developed over the course of forty years, and so the death of one person is unlikely to signal its imminent destruction.

Nevertheless, replacing Nasrallah—not just the man, but the cultish icon—will be a heavy lift whose chances of success are improbable at best, leaving his death as perhaps the one obstacle Hezbollah may not be able to overcome. If, in time, Nasrallah’s demise contributes to the dissolution of the organization that had become so identified with his person during his lifetime, the world will be better off for it.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News