Abstract: The Iran-backed Houthi movement has delivered a strong military performance in the year of anti-Israel and anti-shipping warfare since October 2023. They seem to be aiming to be the ‘first in, last out,’ meaning the first to cross key thresholds during the war (for instance, attack Israel’s major cities) and the last to stop fighting (refusing to be deterred by Israeli or Anglo-American strikes inside Yemen). Facing weak domestic opposition and arguably strengthening their maritime line of supply to Iran, the Houthis are stronger, more technically proficient, and more prominent members of the Axis of Resistance than they were at the war’s outset. The Houthis can now exploit new opportunities by cooperating with other Axis of Resistance players in Iraq as well as with Russia, and they could offer Yemen as a platform from which Iran can deploy advanced weapons against Israel and the West without drawing direct retaliation.

In the year since the October 7, 2023, atrocities, Yemen’s Houthi movement1 a is arguably (in the author’s view) the “Axis of Resistance”2 member that has gained the most newfound recognition on the global stage. It was the Houthis who committed most quickly to support Hamas after October 7, including their dramatic October 31, 2023, launch of the first-ever medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) against Israel by a member of the Axis of Resistance, Iran included.3 Among the axis, only the Houthis—formally known as Ansar Allah (Partisans of God), and (since February 17, 2024) once again sanctioned by the United States for terrorismb—have struck and sunk commercial ships in support of Hamas.4 After a year of notable setbacks for the axis—loss of terrain and leaders by Hamas,5 the deaths of Iranian and Iraqi commanders,6 an underwhelming Iranian strategic strike on Israel,7 heavy leadership losses for Hezbollah (including overall leader Hassan Nasrallah),8 and now Israeli ground incursions into Lebanon9—the Houthis have arguably weathered the year of war without suffering major setbacks.c

This study aims to update the April 2024 study in CTC Sentinel,10 which looked in detail at the Houthi war effort against Israel, the United States, and the United Kingdom, and global shipping from October 2023 to a data cut-off of April 11, 2024.11 This article also builds on two other foundational CTC Sentinel pieces: the September 2018 analysis12 of the military evolution of the movement and the October 2022 study (co-authored with Adnan Jabrani and Casey Coombs)13 that provided an in-depth profile of the Houthi p0litical-military leadership, its core motivations, and the considerable extent of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Lebanese Hezbollah influence within the movement.14

The sections below will take forward (to the time of writing (October 1, 2024, for news events, and an attack data cut-off of August 31, 2024)) the analysis of the military development of the Houthi movement. The analysis will draw on open-source reporting of Houthi military activities, which includes vast amounts of marine traffic analysis, social media, and broadcast media imagery, and U.S. and U.K. government announcements regarding military operations. The piece will also draw heavily on the collation and analysis work undertaken by Noam Raydan and Farzin Nadimi at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s Maritime Spotlight platform,15 which maps and analyses Houthi attacks on shipping, and the Joint Maritime Information Center (JMIC), run by the UK Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO).16 Some data has been drawn from contacts in Western naval and intelligence services, and from contacts in Yemen with extensive on-the-ground access in Houthi-held areas.

The article starts by summarizing the trends visible in Houthi military activities in the second half of the post-October 7 period, from April to September 2024. With the broad outlines set, a detailed analysis follows. Houthi military performance will be dissected in terms of the operational tempo of Houthi attacks, the geographic reach demonstrated in Houthi strikes, and the evolution of Houthi tactics and preferred weapons systems. Special focus will be directed at the issue of why the Houthis strike the ships they do, with a view to better understanding the real level of intentionality (or otherwise) in Houthi targeting of specific vessels. The article will conclude with assessment of the impact of U.S.-led military operations to protect shipping and an update to the April 2024 CTC Sentinel assessment of the Houthi movement’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.17

This map shows a selection of ships (white diamonds) attacked by Houthi stand-off weapons (missiles and/or UAVs). The range ellipses show distances from the most easterly Houthi launch areas in Abyan, 300km in yellow, 600km in white, and 1,000km in red. Houthi anti-ship ballistic missile hits or very near misses in the 300-600km range band—such as the strikes on the Groton in August—are significant feats of marksmanship. The ships attacks farther out beyond 1,000km distance are likely to have been tracked by Houthi or Iranian vessels using radar or visual shadowing and communicating these targeting cues to long-range one-way attack UAVs capable of receiving mid-course corrections to their route planning software. (The green diamond shows the extension of Houthi integrated long-range missile/UAV strikes alongside USV/drone boat flotillas, called “complex attacks” due to the difficulty of coordinating such multi-weapon attacks.)

Recent Trends in the Houthi War Effort

The overall trend in the Houthi war effort since the last CTC Sentinel analysis in April, and more broadly across the entire post-October 2024 period, has been the successful continuation and improvement of Houthi attacks on shipping and on Israel. Despite the commitment of significant U.S., European, and Indian naval forces, the Houthi anti-shipping campaign was not suspended at any point.d Escalating U.S. and U.K. military strikes on Houthi targets in Yemen also did not end the Houthi anti-shipping campaign or even significantly reduce its operational tempo.18 If anything, in the author’s view, the Houthis have arguably improved their effectiveness and efficiency as the war has progressed, by learning lessons and taking advantage of fluctuating U.S. aircraft carrier presence in the Red Sea. In the manner of an underdog boxer trying to ‘go the distance’ to the final bell,e the Houthis have shown resilience and resisted a superpower’s effort to suppress their anti-shipping campaign. The Houthis also weathered a heavy Israeli retaliatory strike on one of their two main port complexes and continued to attack Israel. If, as the April 2024 CTC Sentinel article assessed,19 the Houthi aim is to vault to the front ranks of the Axis of Resistance by demonstrating fearlessness and pain tolerance in support of Hamas and in opposition to Israel and the U.S.-U.K. coalition,20 then the Houthis have succeeded. From the perspective of Ansar Allah’s leaders, in this author’s view, the Houthis may see themselves as the main winners in the post-October 2023 conflict.

As the following sections will dissect in detail, the Houthis can claim to have maintained a broadly consistent operational tempo against shipping, with an apparent surge of effort in June and July 2024—precisely at the point that the U.S.-led international effort might have hoped the Houthi arsenals would be emptying and their pace of attacks reducing.f In this author’s view, as the below sections will outline, the resilience of Houthi domestic drone and drone boat production has been demonstrated, as has the movement’s line of supply to Iran-provided experts and resupply of irreplaceable Iran-sourced materiel.21 As this article evidences below, many of the Houthi’s claims—of extended-range attacks in the eastern Indian Ocean or the Mediterranean—appear unfounded and perhaps deliberately falsified, but the Houthis have nonetheless spread growing fear that they can attack shipping beyond the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. Houthi capacity to precisely identify, find, track, and strike ships by their owner’s nationality or ties to Israel may have been greatly overstated, but there are signs that the Houthis are gradually improving their targeting effort. In the author’s view (see “Tactical Evolution” below), the tactical sophistication of Houthi attacks is also steadily increasing from a very low initial base, aided by their ability to operate small boat flotillas in close proximity to the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden shipping lanes.

Updating the SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) from the April 2024 CTC Sentinel article,22 it is sobering to note that assessed Houthi weaknesses—such as the technical deficiencies of their anti-shipping attacks and air defenses—may be less apparent now. Other exploitable Houthi weaknesses, such as their extended maritime line of supply to Iran and related smuggling networks, have not yet been effectively addressed by their adversaries. Regarding potential threats facing the Houthis, Iran has not been effectively levered into making the Houthis cease their attacks; nor has more united Yemeni opposition been aided to present a more urgent land warfare threat to the Houthis that might divert effort and attention from anti-shipping operations. As a result, in this author’s view, the Houthis can look back at the last year of war with satisfaction: Their position has strengthened, enemy countermeasures have been weathered, and they have no imminent threats on the horizon. This strongly suggests that the Houthis will sustain their anti-shipping and anti-Israel attacks as long as a Gaza and/or Lebanon war continues, if not beyond.

Operational Tempo and Geographic Reach

The Houthi military campaign has gone through some distinct stages since October 2023, often (but not always) reflected in the “phases” announced by Houthi leader Abdul Malik al-Houthi.g The key trend has been a Houthi effort to sustain or increase their attacks on shipping and on Israel proper, despite obstacles such as U.S./U.K. airstrikes on launchers or the declining number of shippers using the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.h The liberal Houthi claiming policy, which either accidentally or deliberately appears to claim attacks that have not happened,i hints at their desire to maximize the apparent tempo, reach, and impact of their attacks. With a strong historic focus on propaganda operations, causing the impression of attacks may be as useful to the Houthis as the number of real attacks itself.j

Assessing how many attacks the Houthis have sent into the shipping lanes is an imprecise art because one must factor in both proven and strongly suspected completed attacks (evidenced by hits or near-misses on ships)23 but also strongly suspected un-completed attacks (evidenced by the interception of inbound attacks by naval vessels in the shipping lanes).k Most collators of attack metrics versus commercial ships (such as JMIC and Maritime Spotlight) count only completed attacks on commercial ships. By slotting together JMIC incident data and other shipping data (collated by Maritime Spotlight) with the intercept data, one can gain a fuller picture of how many attacks the Houthis actually launch.

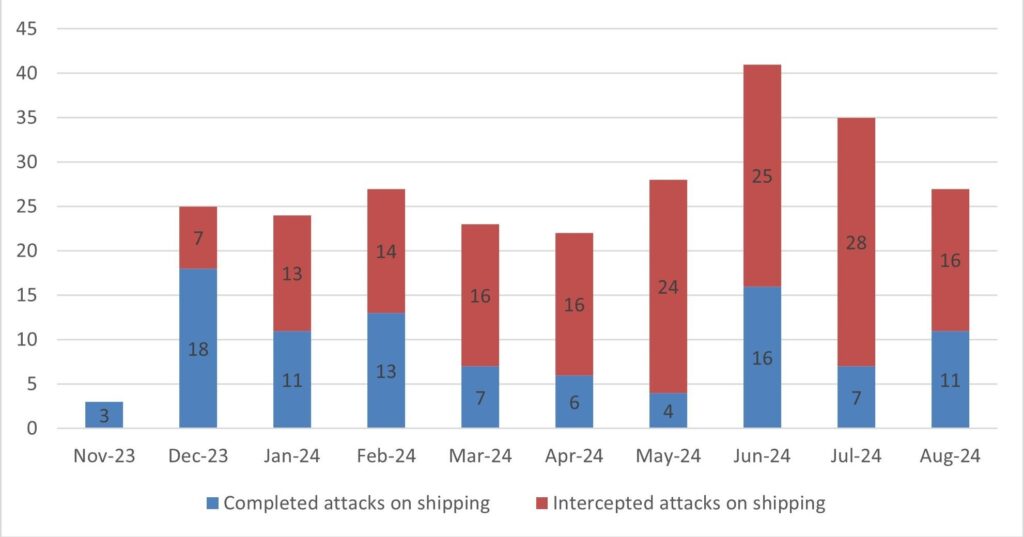

Figure 1 includes the Maritime Spotlight-reported strikes on shipping,24 fused with an additional set of intercepted attacks gathered in the author’s own dataset of U.S., U.K., and European-claimed interceptions in the shipping lanes.25 Even then, these composite figures are probably a slight underreporting of actual strikes, as some attacks will be missed completely by collators,l and some attacks are disrupted in the launch phase by U.S. strikesm in Yemen but may be confused with strikes on storage sites where the weapons are not being readied for use against shipping at that moment.n

Figure 1: Houthi operational tempo against shipping

With these caveats noted, the below statistics tell a story of relative consistency in Houthi anti-shipping efforts, with an upward step-change of attacks in the summer of 2024.26 What the chart clearly does not show is a steady decline in Houthi attack activity in the face of international countermeasures—even during periods of constant U.S. aircraft carrier presence in the Red Sea (November 4, 2023, to April 26, 2024, and May 6, 2024, to June 22, 2024).o The percentage of completed attacks is 38 percent, averaged across the entire coverage period, with minimal variation across the period, suggesting a large proportion of intercepts (especially of slower-moving Houthi drones).27

As well as wanting to be seen to sustain the tempo of their attacks, the Houthis also took pains to portray their geographic reach as ever-expanding. A new phase of claimed long-range strikes started in March 2024, with Houthi communiques threatening to strike out across the Indian Ocean basin as far south as the Cape of Good Hope off South Africa.28 At the start of the Gaza war, there were two anti-shipping attacks on Israel-linked vessels in the eastern Indian Ocean: drone attacks on the CMA CGM Symi (November 24, 2023) and the Chem Pluto (December 23, 2024), both of which occurred closer to India than to Yemen and which may have employed Iranian naval and intelligence assets rather than Houthi ones.p Closer to Yemen, the Houthis did undertake three attacks on vessels at the eastern and southern edges of the Gulf of Aden: one near Djibouti (MSC Orion, April 26, 2024), and two east of Socotra (MSC Sarah V of June 24, 2024, and Maersk Sentosa, July 9, 2024).29 A rash of claimed attacks in the eastern Indian Ocean by the Houthis appear to be erroneous or deliberately falsified.q A concatenation of these events put a chill on Indian Ocean shipping and resulted in some shipping lines taking longer mid-ocean routes to avoid the Yemeni and Horn of African littoral.30 As has often been the case, an inflated perception of Houthi capability and aggressiveness may have achieved the effect the Houthis were seeking.

Houthi Direct Attacks on Israel

Houthi attacks against Israel itself were never numerous and have become rarer as the war has dragged on. Direct Houthi attacks on Israel were most numerous in November 2023, with five attacks in that month following the first-ever MRBM attack on Israel by an ‘Axis of Resistance’ member on October 31, 2024. Thereafter, Houthi-claimed direct attacks on Israel averaged just three per month in December 2023 to August 2024.r

Of these Houthi-claimed direct attacks on Israel, a large proportion (10 of 27, or 37 percent) are claimed to have originated in Iraq,31 where the Houthis have had an increasingly visible presence as 2024 unfolded.32 The Houthis and the Islamic Resistance in Iraq (IRI)33 began to jointly claim attacks on Israel from June 6, 2024, onward.34 The IRI is an online brand used since October 2023 to gather together and anonymize the claims of Iran-backed militants in Iraq as they attacked Israeli and U.S. targets, purportedly in connection to the Gaza war.35 From June 6 to July 15, IRI and the Houthis (the latter using the moniker “Yemeni Armed Forces”) jointly claimed six long-range attacks on Israel-linked ships in Israeli Mediterranean coastal waters or harbors, plus four attacks on Israeli onshore port facilities in Eilat, Haifa, and Ashdod.36 These attacks appear to be servicing Abdul Malik al-Houthi’s May 3 instruction to commence the fourth phase of the anti-shipping war in which any ships interacting with Israeli ports should be struck—not only those closest to the Houthis in Eilat but also those interacting with Israel’s Mediterranean ports.37

As is the case with more than 169 drone and missile attacks on Israeli land targets solely claimed by the IRI (at the time of writing on September 24, 2024),38 it is almost impossible to verify that these Houthi-IRI launches occurred,s and it appears likely (based on multi-source analysis) that very few of the attacks reached Israel.t As attacks on shipping are more likely to be reported (via systems like JMIC), it might be expected that more evidence would exist of the six Houthi-IRI-claimed long-range attacks on Israel-linked ships in Israeli Mediterranean coastal waters or harbors,u yet these also cannot be confirmed.39 An earlier set of three Houthi-claimed (i.e., without IRI) long-range strikes on Israel-linked ships in the eastern Mediterranean in the May 15-29, 2024, period also do not correspond with maritime security incident reporting, casting doubt on the fidelity of the claims.v However, the June 30, 2024, killing of a mid-level Houthi officer (by a U.S. airstrike) at a drone or missile launch site in Iraq does lend additional credence to the claims of Houthi-IRI joint operations.40

While Houthi attacks on Israel have been sporadic and ineffective, they have occasionally been spectacular. MRBM strikes were launched on Israel on June 341 and July 2142 (both on Eilat), and September 17. The latter case was claimed by the Houthis as the first MRBM (out of seven efforts) to penetrate Israel’s Arrow and Iron Dome systems,43 with either a whole missile or intercepted debris falling in an area 15 kilometers from Ben Gurion airport and 25 kilometers from Tel Aviv—wounding nine people in this civilian area,44 which neither Iran nor Hezbollah has attacked since the Gaza war started.45 Though the MRBM was claimed to be a new “hypersonic” design by the Houthis,46 there has been no Israeli or Western admission of a hypersonic attack, and it was more likely an extended-range supersonic MRBM such as the Houthi Burkan-3/Zulfiqar.w Since then, one more MRBM was fired by the Houthis at Israel (on September 27, 2024), again being intercepted.47

A final notable Houthi strike on Israel was the July 19, 2024, drone attack on the center 0f Tel Aviv, which killed one Israeli civilian and injured at least four—once again, an action that neither Iran nor Hezbollah has dared to take since the outset of the Gaza war.48 The drone, named Jaffa by the Houthis (the Arabic name for the Tel Aviv area) was an extended-range Iranian-made Sammad-3 drone.49 The drone penetrated Israel’s battle-tested, low-level defenses by arriving from the west, over the Mediterranean coast, after apparently having taken a very long route via the African continent.50 U.S. and Israeli officials speaking on condition of anonymity confirmed that it traveled via Eritrea, Sudan, and Egypt, thus avoiding the picket line of U.S. and European air defense vessels in the Suez area, and bypassing Israel’s own main south-facing defenses.51 While the tactical surprise generated by the intricate and well-planned flightpath will be difficult to replicate, the incident demonstrated the higher-end of Houthi technical capability, potentially utilizing Iranian or Hezbollah route planning assistance, in this author’s view. In finding a new—but fleeting—way to penetrate Israeli defenses, the July 19, 2024, drone attack on Tel Aviv is reminiscent of the March 19, 2024, cruise missile strike on Eilat,52 another ‘first’ where successful penetration was enabled by elaborate route planning, that time via central Iraq and Jordan airspace.53

Israel’s powerful counterstrike to the Tel Aviv drone attack—Operation Outstretched Arm, the July 20, 2024, destruction of a significant portion of the Houthi oil storage infrastructure at Hodeida54—was probably painful to the Houthis, as was the September 29, 2024, follow-on strike on Hodeida and Ras Issa ports.55 However, these blows also (in the author’s view) brought the Houthis attention and recognition as the ‘Axis of Resistance’ member hitting Israel the hardest and in the most novel and spectacular ways.56 The July 21 Houthi MRBM strike at Israel was one immediate response to the July 20, 2024, Hodeida strike,57 and another was Abdul Malik al-Houthi’s statement the same day that the fifth phase of Houthi military operations in the current war would involve moving “to a new level of anti-Israel operations.”58 He added that the “Yemeni people are pleased to be in direct confrontation with the Israeli enemy.”59 A new September 27, 2024, MRBM strike on Israel drew a further September 29, 2024, Israeli strike on Hodeida and Ras Issa.60

This map shows a selection of ships (green diamonds) attacked by Houthi forces with integrated long-range missile/UAV strikes alongside USV/drone boat flotillas, called “complex attacks” due to the difficulty of coordinating such multi-weapon attacks. These events have sunk one vessel (Tutor) and badly damaged another (Sounion). They are particularly dangerous because the Houthis use boat flotilla to maintain contact with a target vessel, allowing updated coordinates to be sent to missile and UAV attacks. These kind of “wolf pack” tactics can also allow the Houthis to re-attack drifting and abandoned vessels with additional USV strikes or even boarding parties with demolition charges. The extension of such attacks into the Gulf of Aden (see Northwind, attacked August 21, 2024) suggests that wolf packs can pass through the Bab el-Mandab and attack targets outside the Red Sea.

The Puzzle of Houthi Targeting Choices

Since November 2023, risk analysts, shipping companies, and insurers have all put a great deal of effort into understanding why the Houthis do or do not target vessels in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.61 The Houthi clearly employ a kind of elective and selective targeting because only a tiny proportion of ships using the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden have been targeted. For example, there was still an average of 852 ships a month transiting the Bab el-Mandab in February to August 2024,62 the level at which the Red Sea reset after an initial drop from pre-war levels of over 2,100 ship transits each month.63 Of these 850-odd transits,64 the Houthis have, in the most intense month of attacks in June 2024, completed or attempted attacks on only 4.9 percent of ships.65 That means 95.1 percent of ships transited the Red Sea without being attacked in that month,66 underlining the manner in which the Houthis have a very large universe of potential targets to choose from, even when the Red Sea is less busy.

How do the Houthis choose their targets out of this mass of ships? Their main source of targeting guidance is the Houthi leader Abdul Malik al-Houthi, whose announced phases of the war have tended to focus on defining the categories of ships that may be legitimately targeted; the first phase (November 14 to December 9, 2023) included Israel-linked ships in the Red Sea;67 then the second phase (December 9, 2023, to January 12, 2024) broadened to all ships headed to Israeli ports;68 and the third phase (January 12 to May 3, 2024) included all U.S. and U.K. ships;69 and the fourth phase (May 3, 2024, to the time of publication) added in any ships owned or operated by companies whose vessels service Israeli ports.70

All of these categorizations require a degree of knowledge about the ownership, management, and vessel movement and port visits of commercial shipping. This data can be gained from open-source websites, but care and experience are required to differentiate between current and outdated information. As noted by Maritime Spotlight founding editor Noam Raydan, the Houthis appear to have started the war with knowledge about shipping lines and vessels that Iran had previously linked to Israeli owners and Israeli management—and which Iran had often targeted in the Persian Gulf in the 2019-2023 period.71 To this short list, the Houthis also added new research on shipping assets linked to Israel and then (after January 12, 2024) also ships linked to the United States and the United Kingdom.72 In the fourth phase of anti-shipping attacks undertaken since May 3, 2024, the Houthis will have needed to try to identify vessels not directly involved in Israeli trade but owned or managed by companies and individuals with apparent business in Israel or even personal connections to Israel.73 The number of vessels tangentially linked to Israel, the United States, or the United Kingdom provides a very wide set of target options.

The broadening net of targets authorized by Abdul Malik al-Houthi has also included many Russian-linked and Chinese-linked vessels.x These great powers should, in theory, be well-positioned to negotiate safe passage due to their geopolitical alignment with the anti-Western ‘Axis of Resistance,’y yet they have both seen their cargos and vessels attacked repeatedly.z One reason may be the sheer availability of such targets: As the U.S. Energy Information Administration noted, nearly 74 percent of the southbound Red Sea oil traffic in the first half of 2023,74 just before the war started, was made up of Russian oil cargos carried by the so-called “dark fleet,” often headed to East Asia.75 As LNG tankers and major global shipping lines abandoned the lower Red Sea early in the conflict,76 an even higher proportion of the remaining Red Sea transits was presumably (in the author’s view) made up by these smaller, cost-conscious, and risk-acceptant shippers willing to risk the journey. These same shippers have often, in the past, brought Russian oil to Israel, and are therefore perfectly valid targets from a Houthi perspective.77

JMIC statistics suggest that 14 percent of ships attacked by the Houthis from November 19, 2023, to August 31, 2024, were targeted because outdated ownership data triggered the extant Houthi targeting criteria.78 In some cases vessels carrying Russian oil, notably Andromeda Star, have also been misidentified with consulted outdated materials as British-owned and attacked.aa In other cases, Chinese-owned vessels such as the Pumba have been attacked after being identified as U.K.-owned by outdated ownership intelligence.ab

Can the Houthis Maintain a Target Lock?

If one problem is incorrect characterization of whether a ship meets the targeting criteria, a parallel problem is whether the Houthis have a sufficiently good ability to differentiate and track targets during an attack. If they do not, then it is very possible (in the author’s view) that they may undertake attacks on a certain ship but end up striking a different one. Quite a lot of evidence supports this theory. First, JMIC statistics suggest that as high as 37 percent of ships attacked by the Houthis from November 19, 2023, to August 31, 2024, did not meet the Houthis’ own extant targeting criteria.79 Second, the Houthis have struck Iranian shipsac and vessels that had recently left Houthi ports,ad or which were visiting Houthi ports,ae all categories of vessel that would presumably have a lower risk of being intentionally targeted.

Third, the Houthis have frequently appeared confused about which ships they struck:af for instance, claiming hits on multiple ships on July 11, 2024, with no apparent knowledge of the presence of the only actual ship struck (the Russian oil-bearing Rostrom Stoic), or the unwitting Houthi targeting of a Saudi tanker, Amjad, on September 2, 2024, which the Houthis mistook for the Russian oil-bearing Blue Lagoon 1.80 Fourth, the Houthis have sometimes claimed to hit ships that are not physically present in the targeted waterway: For instance, the May 7, 2024, claim to have targeted the MSC Michela in the Red Sea when the ship (and indeed all MSC vessels) are no longer using the Red Sea, and the Michela was instead in the Atlantic Ocean.81

To understand how the Houthis “find, fix and finish”ag a ship, once they think they have identified a legitimate target, it is important to look at the sensors available to them. Wide-area surveillance giving a ‘common operational picture’ of what vessels are visiting the Red Sea is mostly provided by ship-based transponders, the Automatic Identification System (AIS).82 This system—available in simple form via non-subscription websites and in fuller form via subscription services—accurately maps all vessels in a maritime space with a velocity vector (indicating speed and heading), ship name, classification, call sign, registration numbers, and other information.83 To reduce the risk of AIS being used to predict the location of a vessel (say, in the three to five minutes flight time of an Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile (ASBM) at 300 kilometers distance),84 the UK Maritime Trade Organization advised from June 13 onward that vessels weigh the navigational and collision risks of turning their AIS off in high-threats areas of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, and consider turning their AIS off when under attack and altering course in order to prevent their targeting by dead reckoning (i.e., projecting their future location due to their bearing and speed).85

AIS is likely not the only source of targeting information used by the Houthis, not least as the JMIC data shows that 13 percent of attacks have successfully struck a ship even when AIS was turned off. There are indications that long-range electronic intelligence (ELINT) is used by the Houthis to track ships, even those with their AIS transponders switched off. For example, JMIC guidance stresses the need to reduce “non-essential emissions: other than AIS such as ‘intraship UHF/VHF transmissions.’”86 U.S. and U.K. naval officers privately confirm that the Houthis do listen in to bridge-to-bridge communications.87 The United States and the United Kingdom seem to have tried to reduce Houthi ELINT capabilities: As noted in the April 2024 CTC Sentinel article,88 the United States undertook multiple sequences of airstrikes in 2023 and 2024 on retransmission towers and GSM cell towers on high ground overlooking the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.89 Cellphone emissions close to shore may also be vulnerable to direction-finding,90 not least because the Houthis control the key Yemeni telecommunications service providers, who are based in Sanaa.91 It is also possible the Houthis have found ways to subscribe to commercial services that can triangulate terrestrial radio and combine it with AIS tracking. The Houthis are known to have received so-called Virtual Radar Receivers from Iran92 that can create a targeting solution for aerial targets by fusing together open-source transponder and radio detection services.93 ah In the author’s view, the Houthis have probably already (with Iranian help) developed similar systems to combine vessel monitoring and radio direction-finding data.

In a final addition to this sensor network, the Houthis also probably utilize close-in sensors, such as surveillance UAVs, ship-borne AIS and radio monitoring, and visual scanning from boats.94 At the outset of the conflict, the Houthis appear to have received radar and electronic intelligence steers from Iranian vessels95 (such as Iranian frigates purportedly undertaking counter-piracy patrols,ai or various Iranian spy ships before they left the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden by mid-April 2024).aj More recently, Houthi small boat flotillas have made and sustained contact with targeted vessels, flying small UAVs near them96 and maintaining a visual link in order to provide updated location information to long-range strike systems (like ASBMs) and to observe and correct the fall-of-shot.97

By achieving closer shadowing of target vessels (see “Tactical Evolution” below), the Houthis appear to be reducing the time-in-flight limitation of their long-range strike systems (which can exceed 100 minutes for a drone flying 300 kilometers, during which time a ship can move by as much as 75 kilometers).98 Houthi missiles and drones may carry terminal guidance systems—certainly semi-active radar homing for anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs),99 also electro-optical cameras in UAVs,100 and possibly (though this is unconfirmed) some form of guidance system in some ASBMs as well.101 The combination of wide-area surveillance, close-in target shadowing, and terminal guidance has allowed the Houthis to achieve some impressive feats of marksmanship, such as an apparent near-miss on a U.S. aircraft carrierak and a number of hits or very close misses by ASBMs on ships approximately 150-200 kilometers from launch points.al

Tactical Evolution

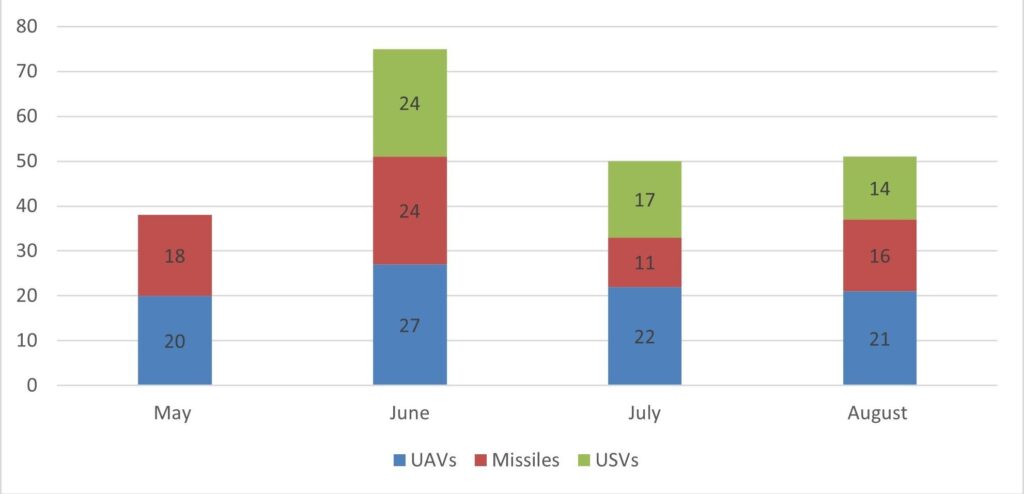

The prior April 2024 CTC Sentinel study on the Houthi war effort in October 2023 to April 2024 provided an in-depth review of Houthi anti-shipping weapons—the Mohit and Asef ASBMs, the Al-Mandab-2 anti-ship cruise missile, a variety of fixed and delta-wing explosive-carrying UAVs, plus explosive drone boats (unmanned surface vehicles, or USVs).102 This study will not repeat the lengthy profiles of these weapons and how they have been employed by the Houthis, only insofar as their mode of employment has changed significantly since then. The April 2024 study anticipated a gradual depletion of higher-end systems like ASBMs, but this did not manifest.103 The following chart (Figure 2) shows numbers of projectiles detected by the author as having been employed by the Houthis in anti-shipping attacks since the end of April 2024.104 Like all attack data, this is an imprecise art and is only meant to be indicative of the number of missiles,am UAVs, and USVs reported by coalition forces as intercepted during attacks, or reported by shippers impacting near or on vessels in proven attacks. Trends include the rise in attacks by explosive drone boats (USVs) in the summer; a more even spread of attack types; and a consistent drumbeat of UAV attacks, probably reflecting the relative ease of producing such systems inside Yemen.105

Figure 2: Houthi expenditure of anti-shipping weapons, May-August 2024

In qualitative terms, the main change in Houthi anti-shipping attacks was the continual refinement of tactics regarding the combination of weapons systems. Three stages of development can be observed; in each case, the tactics were first applied in the Red Sea and then were extended to the Gulf of Aden.106 The stages overlap and are not exclusive—in many cases, the Houthis mixed and matched older and newer tactics—but they do seem to have unfolded as a progression to more complex operations.107

Single-system stand-off. After a brief period of failing to replicate the seizure of the Galaxy Leader, the Houthis commenced stand-off attacks in December 2023 to late May 2024, largely using either UAVs or ASBMs or cruise missiles but not a mix.108 Accurate ASBM shots became regular in the Red Sea toward the end of June 2024 and continued through mid-July.an They extended into the Gulf of Aden slightly later.ao

Multi-system stand-off. The Houthis appear to have begun mixing UAVs and ASBMs or other missiles in series of attacks on single vessels in the Red Sea from the end of May and into early June.ap This period witnessed torturous chases in which individual vessels were bombarded with missile and drone attacks that followed them for many hours,aq in one case throughout the ship’s transit from the Gulf of Aden all the way to the central Red Sea.ar This kind of action gave a sense of the targets being tracked effectively and periodically targeted in a kind of ‘pursuit by fire.’

All-systems, close-up, and stand-off. The third stage of development also overlapped the first two, manifesting first in the Red Sea, and was characterized by much greater involvement of Houthi small boat flotillas, typically including at least one USV.109 These ‘hunter-killer’ packs first targeted the bulk carrier Tutor in the Red Sea on June 12, causing the vessel to sink on June 18, only the second ship to be sunk (at the time of publication) by the Houthis.110 The Tutor attack was notable for a successful “tail-chase” by at least one explosive drone boat that crippled the vessel,111 as followed by subsequent attacks on the stranded and abandoned vessel that may have included UAVs, ASBMs, and possibly demolition charges placed by Houthis on small boats.at Such wolf pack tactics—slowing or stopping the target, then maintaining contact with a wounded vessel and continuing to attack—was then replicated (albeit without new sinkings) in the Red Seaau and later also the Gulf of Aden.av A clear example of this tactics was the attack on the Sounion between August 21-23, when a determined wolf pack raked the vessel with close-in medium weapons fireaw from small craft and detonated at least one USV or missile near enough the ship to cause it to lose power.112 While evacuating the crew, a coalition naval vessel destroyed another nearby USV. Days later, while adrift and unguarded, the Sounion was boarded by Houthi commandos who set barrels of explosive on the deck and detonated them in a vivid videoed propaganda attack that demonstrated almost complete Houthi freedom of action.113

As the author’s April 2024 CTC Sentinel article noted, the Houthis were extensively drilling their fast attack boat and USV flotilla between early August 2023 and the outset of the Gaza war in October,114 probably related to rising U.S.-Iran naval tensions in the Arabian Gulf, where Iran had made six attacks on Israeli or U.S.-linked vessels between February and July 2023.ax In a sense, the Houthi anti-shipping campaign has returned to its roots—albeit now with ASBMs and other weapons incorporated into the attacks of these wolf packs.115 Houthi naval commander Brigadier General Mansour al-Saadi had boasted in mid-December that around 80 such USVs had been stockpiled,116 and this author’s April 2024 report noted that very few of these had been used at that time, but many have been subsequently employed in June-August 2024.117 The Houthi flotilla utilizes fishing boats, islands, and even foreign coastlines (in Sudan, Eritrea, and Somalia) as sustainment hubs,118 exploiting restrictive coalition rules of engagement to merge within civilian traffic.119 The Houthi flotilla has employed tactical drones, electronic intelligence-gathering equipment, and AIS trackers to shadow and report on target ships,120 with periodic reports of them approaching or hailing vessels to confirm their identity.121 Houthi flotilla are very rarely attacked and do not appear to suffer communication problems with the mainland.122 This would seem (in the author’s view) to be from the Houthi perspective an ideal combination of forward observation and close-in attack options, backed-up by long-range strike capabilities that can now be assured of updated information on ship locations.

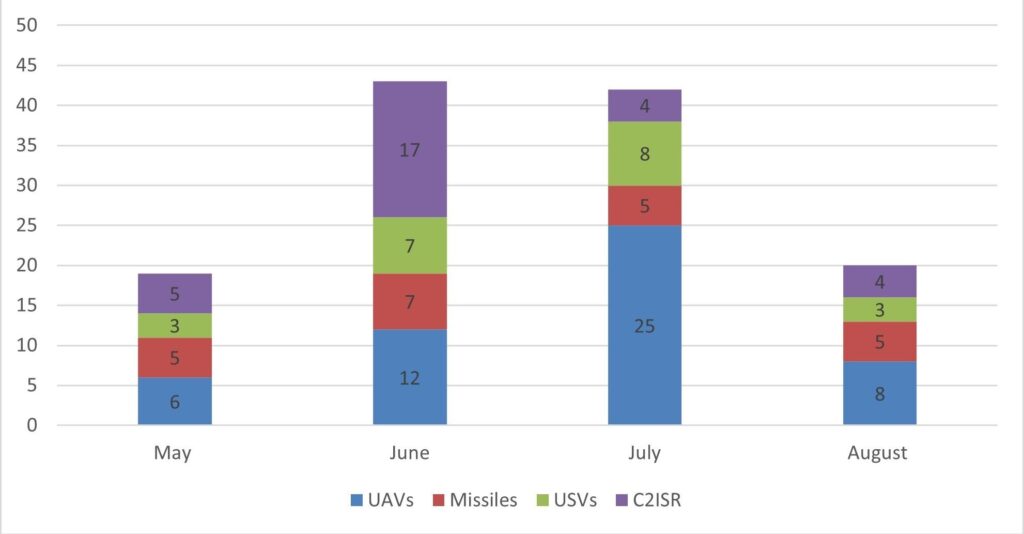

Figure 3: U.S.-U.K. strikes inside Yemen, May-August 2024

The Balance Sheet Between the Houthi and U.S. Efforts

Operations Prosperity Guardian (the U.S.-led escort and interception effort),123 Aspides (the E.U. equivalent),124 and Poseidon Archer (U.S.-U.K. airstrikes inside Houthi-held Yemen)125 have been marked by undoubted feats of valor, endurance, and professionalism. For U.S., U.K., and E.U. naval forces, these operations arguably (in the view of the author) represent the most intense maritime trial-by-fire since conflicts like the Iran-Iraq War and the Falklands.ay Operating for extended periods in an unforgiving, high-threat engagement zone, the U.S. and partner navies have been fortunate not to have suffered a serious missile impact so far, and there have been near-misses.az (As recently as September 27, Houthis forces appear to have fired a salvo of cruise missiles and drones at or near a cluster of U.S. military vessels, albeit with all the unspecified number of munitions being intercepted.126) The Houthis (and the broader Axis of Resistance) might achieve a significant propaganda boon if a U.S. vessel were badly damaged or sunk, and even the withdrawal of a U.S. carrier battle group from the Red Sea was loudly trumpeted by the Houthis as a victory. In the sphere of air defense, the Houthis have not come close to threatening U.S.-manned aircraft, but they have taken a heavy toll on the U.S. drone fleet, destroying at least nine MQ-9 Reapers between November 8, 2023, and October 1, 2024.ba

The United States and partner forces in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden have clearly reduced the damage that the Houthis could do to global shipping, as evidenced by an assessed 62 percent interception rate shown in Figure 1 of this study. In addition to interception of launched attacks, the U.S.-U.K. air campaign over Yemen has undoubtedly limited Houthi capabilities to find and fix commercial ships—for instance, a determined effort to blind the Houthi targeting system with intensified strikes on Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) in June 2024.bb

However, the reduction of U.S. naval presence in the Red Sea, particularly the withdrawal of the U.S. aircraft carrier USS Eisenhower in late June, has arguably opened up the space needed for the Houthis to redeploy their small boat flotillas and recommence more effective wolf pack tactics.127 Of note, naval assets do not appear to have been sufficient to guard the Tutor and the Sounion after they lost power and were abandoned,128 allowing the Houthis to access these stricken ships. Houthi attack patterns in June and July appeared to show greater freedom of movement for their small boat and USV flotillas and an enhanced ability to follow and repeatedly attack ships.129 In sum, in the view of the author, freedom of safe navigation has clearly not been restored by the efforts of international navies, respectable shippers have not been assured, and Houthi attacks are not deterred.

Equally concerning, one of the greatest exploitable weaknesses of the Houthis—significant reliance on a maritime line of supply to Iran, for military resupply and for financing—has not been addressed by the international naval presence in the Red Sea. Whatever military supplies cannot be made entirely locally in Yemen—notably missile guidance, engines, fuel, warheads, and C4ISR systems130—has to be squeezed through the Houthi Red Sea ports or smuggled overland through enemy territory controlled by Yemen’s internationally recognized government. Yet, the policing of the U.N. embargo on arms deliveries to the Houthis seems to have slackened during the current conflict, not tightened, in the author’s view. At least six large ships have visited the Houthi-held port of Hodeida in 2024 without stopping for inspection, as required by a U.N. Security Council resolution, at the UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM) hub at Djibouti.131 This is unusual behavior that only started in the spring of 2024 when the war was underway.bc On May 13, 2024, the U.K. representative to the United Nations, Barbara Woodward, revealed that as many as 500 truckloads of material were known to have bypassed inspections by this method.132 Alongside the risk of large ship transfers, which are legally difficult to interdict as they require flag-state permission to board,133 there have also been a trickle of large dhows and fishing boats entering the Houthi-held inlets south and north of Hodeida (which were detailed in the April 2024 article),134 with around 12 ships subsequently docking there in May-August 2024, according to the author’s local contacts.135 On June 26-27, 2024, the Houthis also managed to overcome the aerial embargo by diverting a Yemenia flight to Amman so that it instead landed in Beirut, Lebanon, and returned from there to Sanaa, Yemen.136 What all this points to is the likelihood that the Houthis have been able to sustain their operational tempo—despite increased expenditure of munitions and U.S.-U.K. strikes—because they are being resupplied at an adequate rate.

Updating the SWOT Analysis of the Houthi War Effort

The April 2024 CTC Sentinel study issued an assessment of the demonstrated strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats facing the Houthis in the first period of their war against Israel, the United States, the United Kingdom, and global shipping. As the war turns one year old, the picture is arguably even bleaker for the forces trying to contain the Houthi threat.

The strengths shown by the Houthis are abundant and have been reinforced by events: Their pain tolerance was illustrated by their apparent insensitivity to having at least a third of their oil storage facilities destroyed by Israel on July 20, which they answered immediately by firing a ballistic missile at Israel and vowing to double their efforts to strike the Israeli state. The strategic depth of Yemen—its size and mountainous terrain—had complicated the task of finding and destroying Houthi missile and drone systems.bd The weak and divided state of the anti-Houthi opposition on the Arabian Peninsula was graphically underlined when a promising Yemeni government economic warfare effort from late May 2024 began to destabilize the Houthi banking system,137 only to have the effort curtailed just days after the Houthi July 7 threat to recommence their missile and drone attacks on Saudi Arabia.138

Some weaknesses identified in April 2024 appear to have been partially addressed by the Houthis. One senior U.S. naval officer with responsibility for the Yemen theater told the author in mid-2024, “We came to see that the Houthis are not a ragtag force: they are resourced, trained, funded, stocked, supplied, and resupplied.”139 As noted, the Houthi line of supply to Iran has probably strengthened, with no apparent cost for bypassing a U.N. inspection regime.140 As outlined above, Houthi air defenses are gradually strengthening, albeit only against drones, and the technical weakness of long-range target acquisition and tracking are arguably being mitigated with new wolf pack flotilla tactics. As one U.K. naval officer with experience of the Red Sea operations told the author: “Iran has excellent marine traffic intelligence; the Houthis don’t.”141 Yet, there is some evidence to suggest that the Houthis have learned how to offset this weakness and track intended targets.142 As this author noted previously, the Houthis could not operate in proximity to strong Western naval forces in the Red Sea, but the thinning out of these forces offsets the Houthi weakness in tactical proficiency. The economic weakness of the Houthi regime was briefly exploited by the Yemeni government before being abruptly turned off by Yemen’s backers—Saudi Arabia, the United Nations, and the United States.

Major opportunities now beckon for the Houthis and the ‘Axis of Resistance,’ with the Houthis arguably having delivered the best military performance of all the axis players in the current war, in the author’s view. There is strong potential for the Houthis to build on their successes in severely constricting one of the world’s busiest global chokepoints, the Bab el-Mandab. International shippers, insurers, and governments must be careful to ensure the Houthis do not learn how to effectively monetize their ability to shut the Bab el-Mandab and Suez Canal to selected nations or shipping companies, which can be levered into a lucrative extortion racket.143 As Houthi targeting capability gets more selective, this terrorist threat finance risk may rise, unless it is actively monitored and deterred through sanctions enforcement.be The caution shown toward the Houthis by international players such as Saudi Arabiabf could make them more aggressive, and this tendency may deepen as the Houthis learn to threaten their way out of tight spots—for instance, using threats of infrastructure attacks to extort political concessions in peace talksbg or, as was tried recently, to coerce the Yemeni government to provide oil revenues to the Houthis.bh

The Houthis’ elevation to a top-tier member of the ‘Axis of Resistance’ presents other opportunities to the whole Iran-led bloc. Under the Houthis, Yemen has become a place from which the Iran threat network can undertake attacks on Israel that Iran itself does not dare to mount—already including ballistic missile and drone attacks on Tel Aviv.144 Yemen might also be used by the axis as a way to mount attacks on other targets—such as U.S. forces—in a way that may not draw retaliation on more pain-sensitive parts of the axis—for instance, Iran. At present, the Houthis have used the boogey-man reputation of hypersonic weapons as an attention-grabber, but in the future, Yemen could be an ideal site for such weapons considering its geographic placement and its proven ability to conceal launch sites in its rugged interior.

Likewise, the expansion of Houthi presence into areas like Iraq—where a senior Houthi missileer was killed by a U.S. strike on June 30, 2024—could put Houthi strike capabilities in new areas such as Saudi Arabia’s northern border,bi the Iraq-Jordanian border,bj and Syria.145 Where Iran and its local partners can sometimes be fearful of the consequences of striking foes such as Israel or the United States, the Houthis may be more willing. This is particularly the case as key Iranian partners like Hamas and increasingly Hezbollah face severe military pressure from Israel. It is intriguing that a more visible Houthi presence in Iraq146 seemed to coincide with the first use by Iraqi groups (under the IRI umbrella) of what the Houthis call the Quds-type land attack cruise missiles (LACM), known in Iran as the 351/Paveh.bk In the author’s view, it is worth investigating whether this capability entered Iraq for the first time precisely because Houthis were on-hand to help Iraqi militias open this new front using unprecedentedly advanced weapons.

The Houthi attacks in the southern Gulf of Aden—south of Socotra and toward Djibouti—hint at what expeditionary Houthi boat flotillas might accomplish one day, off the African littoral and even operating on the eastern coast of Africa in weak state environments like Sudan, al-Shabaab enclaves, and Somalia.bl The Gaza war has shown that the Houthi need to undertake very few real attacks in the Indian Ocean to send a shiver through the global shipping networks. Imagine what a more effective capability could do, in the manner of the German merchant raiders that haunted the Indian Ocean in both world wars.147 Addressing this threat more effectively will very likely be a priority issue for U.S. policymakers in the future, and one that the intelligence community will be called upon to support with analysis.

The Houthis could also view Russian military support as an opportunity. In a recent on-the-record address in Washington, D.C., the U.S. envoy to Yemen, Tim Lenderking, was explicit about the risks of Russo-Houthi partnership, noting: “Their relationship with Russia is extremely troubling … Russia is irritated by our strong policy on Ukraine, and they are seeking other outlets to retaliate, including in Yemen. They have been seeking to arm the Houthis, which would be a game-changer.”148 Lenderking was reflecting widespread press reporting of a potential Iran-brokered Russian supply of Yakhont/P-800 Onik anti-ship cruise missiles to the Houthis, which U.S. comments were probably intended to dissuade.149

Perhaps the only sharp threat facing the Houthis is the possibility that the Axis of Resistance writ large could suffer a crippling number of defeats in the current war—in Gaza, Lebanon, and elsewhere—and that Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah support to the Houthis might not be as available in the future as it has been in the past. For instance, Hassan Nasrallah’s death150 removes one of the most ardent supporters in Lebanon of the Houthi cause, potentially disrupting a key relationship and potentially focusing Hezbollah on its own internal problems. Indeed, one wonders if the abundant manpower of the Houthis could provide a source of outsider regime security forces willing to crack down on local populations where Iran-backed groups are feeling pressure—such as Lebanon, Syria, and even Iraq or Iran.bm

This underlines the unusual potential finding that Iran itself may be more vulnerable than the Houthis. As U.S. Central Command’s General Erik Kurilla told Congress on March 7, 2024, the key to suppressing Iranian partner forces like the Houthis may come in the form of pressuring Iran itself to force the axis to back down151—a kind of inside-out approach in which Iran uses its soft power, its ideological leadership role within the axis, to convince a Houthi ceasefire (probably temporary) in the shipping lanes. If this turns out to be true, this would suggest that it may be easier to try to threaten “the head of the octopus”152 (Iran) than to try to directly coerce its newest and most resilient and aggressive tentacle.

Substantive Notes

[a] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells note that the Houthis are known by a variety of names: “the ‘Houthis’ (al-Houthiyin), the ‘Houthi movement’ (al-Haraka al-Houthiya), ‘Houthist elements’ (al-‘anasir al-Houthiya), ‘Houthi supporters’ (Ansar al-Houthi), or ‘Believing Youth Elements’ (‘Anasir al-Shabab al-Mu’min).”

Citations

[1] Barak Salmoni, Bryce Loidolt, and Madeleine Wells, Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen: The Houthi Phenomenon (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2010), p. 189.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News