Key points

- As debate grows over U.S. policy towards Africa, consideration should be given to altering the continent’s status under the Department of Defense’s Unified Command Plan (UCP).

- Eliminating Africa Command (AFRICOM) under the UCP would both signify a policy shift away from a counterterrorism focus and ease the process of implementing that change within the policymaking bureaucracy.

- Establishing a three-star subcommand, nested under European Command (EUCOM), would still allow the United States to use force in Africa, when necessary, but would reduce the prominence of military power in U.S. policy toward the continent.

- AFRICOM and EUCOM essentially share much of their force structure; this unique relationship would facilitate the transition to the proposed three-star subcommand.

- Altering the U.S. military footprint in Africa should also be considered in the context of any changes to policy and command arrangements. Making specific recommendations at this time is complicated by the opaqueness of the current footprint.

Introduction

A small but growing number of analyses have questioned U.S. policy towards Africa.1 These critiques argue, first, that the United States has allowed counterterrorism to become the primary element of U.S. engagement in Africa with outcomes that have been questionable at best.2 Second, they suggest other priorities—including promoting good governance, bolstering democracy, and encouraging economic growth—as the basis for a more effective approach.3 These proposals are offered with a clear eye: there is no silver-bullet solution to Africa’s challenges. But by prioritizing areas that foster long-term stability in Africa, U.S. policy could produce better results than an immediate focus on kinetic counterterrorism.

This paper examines an understudied aspect of the current U.S. approach: the existence of a dedicated unified combatant command with responsibility for Africa. On the surface, command arrangements may seem like an esoteric concern, but in fact they play a critical role in shaping priorities for U.S. engagement and in distributing bureaucratic weight within policymaking structures.

The central argument presented herein is that a substantive shift in U.S. policy would benefit from downgrading responsibility for Africa under the Unified Command Plan (UCP) to a three-star billet, nested under European Command (EUCOM). The current arrangement—in which responsibility for Africa is assigned to a four-star combatant commander—creates a powerful bureaucratic actor, one with a vested interest in maintaining robust U.S. military engagement in Africa. It will likely be more difficult to recalibrate U.S. policy away from a hard-security focus so long as the command exists in its current form.

Arguing this point is not intended to impugn any individual who leads Africa Command (AFRICOM) or those who work at the command. It is simply to recognize the reality that bureaucratic entities, by nature, are unlikely to support a reduction in their missions. Downgrading AFRICOM’s position within the UCP thus would not only publicly symbolize a change in U.S. policy, it would also facilitate implementation of a new approach.

At the same time, retention of a three-star subcommand would still allow the United States to use military force in Africa, if needed. But such a change in command arrangements would reposition the role of military power, moving it away from the forefront of U.S. engagement.

Structure of the paper

The remainder of this paper explores these ideas in more detail. First, the history of how Africa Command came into being is examined as are past command arrangements for the continent. The history of U.S. military activity in Africa under the Unified Command Plan is discussed. Second, AFRICOM is considered through the lens of the bureaucratic politics literature to give the reader a better sense of the role played by the combatant commands in policy formation. Three case studies are then presented to explore how differing command schemes affected military advocacy for the use of force in Africa. A brief concluding section offers summary thoughts on the future of command arrangements in Africa. Finally, an appendix reviews what is publicly known about the U.S. military footprint in Africa and considers how it could be adjusted in concert with a change in Africa’s status under the UCP.

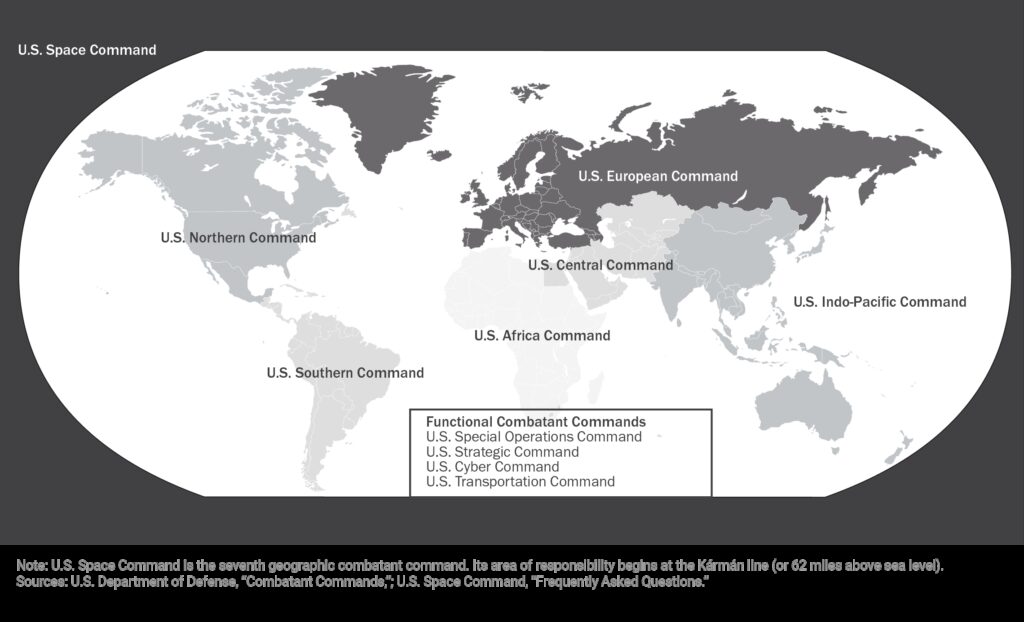

The UCP and the origins of AFRICOM

To begin this discussion, it is useful to formally introduce the Unified Command Plan. It is the internal document through which the Department of Defense delegates command responsibility for specific geographic regions and select functional tasks (e.g., command of nuclear weapons).4 These areas are assigned to a unified combatant commander who controls all of the assets in their regional theater or functional area of responsibility. Currently, there are 11 combatant commands—seven geographic commands and four with functional responsibilities.5

The UCP has been in effect, in one form or another, since it was first adopted in 1946. Unsurprisingly, its intellectual roots lie in the Second World War: the UCP was intended to institutionalize wartime unity of command, whereby a single theater commander was responsible for all forces in his area of operations, regardless of service branch.6

Traditionally, the two major geographic commands under the UCP were European Command and Pacific Command (PACOM), which were established shortly after the war’s end.7 But large areas of the world went unassigned. Surprisingly, this included the Middle East, which did not receive a dedicated command until 1983 when Central Command (CENTCOM) was activated.8

Africa itself was ignored for much of the UCP’s history or, at least, was not assigned priority on a continent-wide basis. During one period, from 1963 to 1971, sub-Saharan Africa was tangentially assigned to Strike Command (STRICOM), a Florida-based command whose primary focus was on joint training and doctrinal development.9 But STRICOM’s remit was simply to oversee broad contingency planning for Africa, as well as other unassigned regions under the UCP; it did not forward-base forces on the continent or conduct routine operations there.10

U.S. unified combatant commands

Specific areas of Africa were also placed under the purview of adjacent geographic commands at various points. For example, European Command held responsibility for select North African states bordering the Mediterranean Sea.11 When Central Command was activated in 1983, its area of responsibility (AOR) included five states in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia).12 At that time, European Command’s AOR was expanded to include not just North Africa, but also all of sub-Saharan Africa, save those states allotted to Central Command.13

To summarize, for the first half of the Unified Command Plan’s existence, much of Africa was often unassigned. Then, from 1983 onwards, responsibility for the continent was assigned primarily to two combatant commanders, each of whom had another geographic focus—either Europe or the Middle East.14 A dedicated command explicitly focused on Africa is thus a comparatively recent development, with AFRICOM not officially activated as a standalone entity until October 2008.

U.S. military operations in Africa prior to AFRICOM

What was U.S. military activity like during this long era without a focused commander for Africa under the UCP? Let’s briefly review the record from the end of the Second World War through the early 2000s, prior to AFRICOM’s activation.

In the early 1960s, the United States conducted three operations in and around the Congo as that country suffered from factional fighting in the wake of independence from Belgium. These missions primarily involved Air Force transportation assets. This was the case in Operation Safari (1960), an evacuation of U.S. citizens, and in Operation New Tape (1960–64), an ongoing mission to deliver humanitarian aid and deploy UN forces.15 The riskiest intervention was the third, Operation Dragon Rouge (1964): the Johnson administration sent a dozen C-130 transport planes from European Command to support a battalion of Belgian paratroopers in undertaking a mass hostage rescue in Leopoldville (Kinshasha).16

In 1978, the Carter administration would similarly use strategic lift to support Belgian and French paratroopers evacuating Western citizens amid renewed fighting in Zaire (Congo). Air Force transports delivered ammunition and fuel to European units and helped deploy a small Pan-African peacekeeping force.17

In 1986, the Reagan administration launched Operation El Dorado Canyon, a punitive airstrike against Libya’s Moammar Gaddafi in response to his support of terrorist operations.

After the Cold War’s end, the administration of George H.W. Bush deployed forces to Somalia in December 1992 to facilitate the delivery of humanitarian aid amidst a famine.18 Known as Operation Restore Hope, that mission’s parameters infamously grew to encompass a hard-security element in the form of action against local militias (Operation Gothic Serpent).19

In the summer of 1994, the United States also briefly sent military units to deliver humanitarian aid to refugee camps in and around Rwanda amidst that country’s civil war (Operation Support Hope).20

In August 1998, two Navy destroyers launched six cruise missiles at a suspected chemical weapons plant in Sudan, as part of the Clinton administration’s response to terrorist attacks against U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania (Operation Infinite Reach).21

Finally, from 1990 through 2003, U.S. Marines led five non-combatant evacuations in West Africa, including three missions to Liberia and one each to the Central African Republic and Sierra Leone.22

The majority of U.S. operations during this time period had a humanitarian focus (e.g., aid delivery, non-combatant evacuations) and eschewed long-term ground deployments. When force was used—e.g., Operations El Dorado Canyon and Infinite Reach—it was usually a contained strike, not an ongoing operation. Casualties were also light for the most part. Two U.S. airmen were lost in the Libyan raid, but there does not appear to have been U.S. fatalities in the other operations discussed above, with one notable exception.

The 1992–1994 Somalia deployment is an outlier in several respects. The mission lasted 16 months with large numbers of troops on the ground, and the United States incurred substantial casualties—32 killed in action and 172 wounded.23

That important case aside, the remainder of U.S. military activity in Africa during this period was both limited in scope and episodic considering the 60-year timespan.24 Some decades saw only a single U.S. military operation in Africa, if that.25 Sea-based forces and air forces based outside Africa were often the primary units involved. In fact, fixed U.S. military infrastructure in Africa during the Cold War and immediately afterwards was minimal, including some periods when the U.S. had no formal bases on the continent.26

Implications of command arrangements

It is natural to begin considering causality here. Was there less U.S. military activity in Africa during this era because there was no focused command for the continent? Or did Africa’s lack of priority in the UCP stem from the limited number of military operations conducted there? One can argue the question both ways, but in either event command arrangements emerge as a relevant factor—whether they simply reflect the level of military activity or drive it.

Either explanation raises the issue of changing Africa’s status under the UCP now if the goal is to scale back U.S. military engagement in deference to other policy approaches. Removing Africa Command could be seen either as mirroring that policy shift or as enabling change by displacing a major bureaucratic actor with an interest in strong U.S. military engagement in Africa. Before exploring that idea in more detail, it is helpful to understand why AFRICOM was created and how the command evolved.

2008: AFRICOM’s activation

By law, the Unified Command Plan is reviewed by the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff every two years, with any alterations requiring presidential approval.27 Some reviews are pro forma, while others are treated as an opportunity to signal policy changes through realignment of command arrangements. For example, in 2018, Pacific Command was rechristened “Indo-Pacific Command” (INDO-PACOM) to reflect the growing strategic relationship between the Indian and Pacific oceans.28 In January 2021, Israel was moved to Central Command’s area of responsibility after decades of being assigned to European Command out of deference to Arab sensitivities. That shift reflected the thawing of relations between Israel and the Gulf states.29 Both moves illustrate how the UCP can reflect U.S. policy priorities.

Along those lines, the UCP was employed to highlight growing U.S. strategic interest in Africa in the mid-2000s. The 2006 review of the UCP eventually led to the creation of Africa Command, which was formally activated two years later after a short interregnum during which the new command was built out from existing resources within European Command.30 AFRICOM’s new area of responsibility encompassed the entire African continent, except for Egypt, which remained with Central Command.31

In the years immediately preceding its activation, there was significant internal debate within the Department of Defense as to whether a full four-star combatant command was required for Africa.32 A plan originally developed by the Joint Staff in 2006 would have assigned responsibility for the continent to a three-star general officer heading a sub-unified command reporting to EUCOM.33 Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld subsequently elevated that recommendation to an independent four-star combatant command, soon to be AFRICOM.34

At the time, the Bush administration was preparing to issue National Security Presidential Directive 50 (NSPD 50), a holistic series of policy initiatives towards Africa. These included efforts in the diplomatic and public health spheres, as well as measures to bolster democracy and support economic growth.35 (Ironically, these are all policy areas many critics argue should be the focus of an alternate U.S. approach to Africa now, as noted earlier.) In the end, it was believed a new unified combatant command was needed to underscore the strategic importance the United States was attaching to Africa.36

The architects of Africa Command intended for it to be a unique entity. It was given an innovative command structure that eschewed the “J-code” associated with U.S. warfighting staffs and incorporated civilian officials from agencies like the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development.37 Proponents frequently spoke of Africa Command as harnessing “smart power,” a fusion of soft power elements with military hard power.38 As the new command’s flag was raised at the Pentagon, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates asserted that AFRICOM’s mission was “not to wage war, but to prevent it.”39

AFRICOM and the Libyan intervention

Good intentions aside, the hard-power aspect quickly came to the fore in Africa Command’s operations. Beginning in March 2011, AFRICOM served as the U.S. lead in an international coalition which undertook two consecutive military operations in Libya: Odyssey Dawn and Unified Protector. The first helped break the siege of rebel areas by Libyan government forces while the second expanded the intervention to actively support the rebels in overthrowing the Libyan dictator, Gaddafi.40

From an operational standpoint, Odyssey Dawn and Unified Protector are generally considered successes: they achieved their intended goals, halting regime action against rebel forces and enabling Gaddafi’s ouster.41 From a strategic perspective, the outcome is far murkier. Unity post-Gaddafi was short-lived, and a six-year civil war ensued in 2014. Humanitarian suffering was widespread.42 Amidst this instability, a number of Islamist terrorist organizations emerged in Libya, including an affiliate of ISIS.43

For Africa Command itself, Libya had two main impacts. First, it set the stage for nearly a decade of ongoing U.S. counterterrorism operations in that country. Africa Command would ultimately execute over 500 manned and unmanned airstrikes in Libya from 2012 through 2019 (i.e., after the end of the initial intervention covered by Odyssey Dawn and Unified Protector).44

Second, the Libyan intervention arguably ended the “smart command” experiment AFRICOM represented and shifted it to a track where it functioned more as a warfighter. After Odyssey Dawn, General Carter Ham, then-commander of Africa Command, observed, “Combatant commands don’t get to choose their missions.”45 Ham further stressed the need for AFRICOM to be able to undertake the full spectrum of military activity including “high-end operations.”46 Punctuating that point, AFRICOM would eventually adopt the traditional J-code military staff used by the other geographic combatant commands.47

From the perspective of U.S. policymaking, this transition introduced a strong bureaucratic actor with a focus on hard-security concerns in Africa, rather than the broader policy goals originally outlined in NSPD 50. While it was hoped AFRICOM would enable these other initiatives, military activity—specifically counterterrorism—seemed to eclipse them in prominence.

Other U.S. military actions under AFRICOM

U.S. action in Somalia reinforced Africa Command’s warfighting role. The U.S. began counterterrorism missions there in 2007, as AFRICOM was in the process of being stood up as an independent command.48 These operations would continue for the next 16 years under Africa Command’s direction, up through the present day. During this period, AFRICOM conducted over 300 airstrikes in Somalia.49 (The most recent of these occurred on July 15, 2024.)50 Africa Command also employs ground forces in Somalia and, in some cases, these have been involved in direct action against al-Shabaab militants. In 2017, a U.S. Navy SEAL was killed in action operating alongside Somali security forces.51 Training and support for the Somali National Army (SNA) has been another priority of U.S. engagement.52

Africa Command has been active elsewhere on the continent. This included an important supporting role in France’s Operation Barkhane, an eight-year counterterrorism mission in the Sahel. Although not involved directly on the ground, AFRICOM is believed to have furnished logistical aid to French forces and provided drone reconnaissance.53 The French eventually abandoned Barkhane with little to show in the way of substantive long-term success.54 Making matters worse, many of their partner states succumbed to military coups toward the operation’s end or shortly thereafter.55

Forces assigned to AFRICOM also appear to have fought an uncertain number of smaller ground engagements in various African countries where the United States has some form of basing infrastructure. U.S. forces were ambushed in Niger in 2017 and Kenya in 2020, resulting in seven American deaths combined.56 Press reports indicate there were at least 10 other attacks on U.S. forces in Niger prior to the 2017 ambush.57 Also in 2017, U.S. Marine Raiders aided Tunisian security forces in fighting Islamist insurgents near Kasserine Pass, with one Marine wounded.58 It is unclear if that was a one-off instance of U.S. forces actively engaging in combat in that North African country.59 AFRICOM also based special operations forces (SOF) on the ground in Libya amidst that country’s civil war, at least raising the possibility they saw combat as well.60

The AFRICOM-EUCOM relationship

A final aspect of AFRICOM’s status under the UCP worth emphasizing is its unique relationship with EUCOM. The two are deeply intertwined in terms of force structure and subordinate commands. Most notable is that Africa Command is actually headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany—not in Africa itself. Also, the majority of AFRICOM’s component commands are shared with EUCOM and are also headquartered in Europe.61

By way of background, component commands are the service-specific forces underneath the unified combatant commander. That is, a given geographic combatant command has a subordinate Army component, Air Force component, Navy component, etc., encompassing all five military services. There also is a sixth component command, dedicated to special operations forces. That component receives its personnel from Special Operations Command (SOCOM), which provides SOF globally to all the geographic combatant commands.62 In AFRICOM’s case, its five service components are all shared with European Command—both the forces themselves and the specific general or flag officer who serves as a given component commander.63 Only AFRICOM’s special operations component is a distinct entity.

The sharing of service components between AFRICOM and EUCOM is a singular arrangement among the geographic combatant commands; all others have separate forces and individual general officers heading their components. It also means if Africa Command were struck from the UCP tomorrow, the forces it draws on would remain in place under European Command. (The exception would be the dedicated special operations personnel assigned to Africa Command, but these would still be available via SOCOM.) Thus, while the proposal for assigning Africa to a three-star general under EUCOM never came to pass—as proposed by the Joint Staff in 2006—in many ways AFRICOM functions as if it did in terms of force structure, albeit with a leader who has the full weight of a four-star combatant commander.

How much does that distinction matter? Perhaps a great deal. Four-star billets are comparatively rare within the U.S. armed forces. As of April 2024, there were only 41 four-star generals and admirals on active duty across the five services, as compared with more than 150 three-stars, and over 600 one- and two-star general and flag officers.64 As noted, there are only 11 unified combatant commanders and just seven that are geographically focused. A four-star geographic combatant commander is a genuinely elite position—both within the U.S. military itself and the broader national security policymaking apparatus. That carries significant cache within policy debates as well as affording the combatant commander direct access to the senior-most decisionmakers.

The next section explores this idea in more detail. It draws on the bureaucratic politics literature to explain why having a dedicated combatant command for Africa matters in terms of policy formation and execution.

AFRICOM through the lens of bureaucratic politics

Graham Allison’s Governmental Politics Model (more commonly referred to as Model III) remains an essential starting point for weighing the impact of bureaucratic actors on national security decision-making. In his seminal work, 1971’s Essence of Decision (revised with Phillip Zelikow in 1999), Allison used the lens of the Cuban Missile Crisis to posit three models for how governments reach decisions.65 Model I assumed the traditional paradigm of government as a unitary actor making rational choices.66 In contrast, Models II and III treat “the government” as a collection of individual actors.67 Allison believed these two models allow for a better explanation of why governments sometimes act in ways that seem inimical to their best interest or otherwise reach suboptimal decisions.68

Model III gained particular traction in academic discussions.69 Allison’s thesis in this model is that foreign policy is the outcome of a competitive game played by multiple bureaucratic players, each with their own interests. Those interests are determined by their policy portfolios, budgetary concerns, and related organizational agendas. Indeed, Model III is sometimes short-handed with the dictum “where you stand depends on where you sit,” an aphorism also called Miles’ Law.70 Allison and Zelikow temper this dictum somewhat in their revised text by arguing it should be read as one’s outlook “is substantially affected by” bureaucratic positioning rather than “is always determined by.”71

Another central aspect of the model is the idea of “action channels,” or pathways along which decision-making is conducted. Access to the action channels is an essential component of a player’s relative weight in the game.72

Applied to AFRICOM, the command constituted a new player with a strong bureaucratic interest in military engagement and hard-security concerns in Africa. (Or at least that was the case from 2011 onwards as the command assumed a more traditional warfighting role rather than the “smart command” model initially envisioned.) Moreover, as a four-star combatant commander, the head of AFRICOM brought to the game substantial weight and immediate access to action channels at the senior-most levels.73 Africa Command, then, was not just an additional player in the policymaking game, but a particularly powerful one.

Allison’s work suggests that if the U.S. approach to Africa is to change, it is necessary to alter the players in the bureaucratic game influencing policy development. In this case, that would mean removing the dedicated combatant command for Africa in deference to other arrangements under the Unified Command Plan.

From a policy perspective, moving away from a military lead in Africa would be easier without a dedicated command for that continent—one that could serve as a strong advocate for maintaining robust U.S. military engagement there. It is unlikely Africa Command would be eager to scale back its operations and basing infrastructure, two prerequisites for a major shift away from counterterrorism as the U.S. policy lead in Africa.

To be clear, the implication is not that AFRICOM is off conducting military operations of its own accord. Africa Command implements policy as decided by the president. But the command does have an important impact on that policymaking process, which ultimately generates options for the president and other senior decisionmakers to consider. This includes questions of whether to sustain or curtail ongoing combat operations or even initiate new ones. Miles’ Law—which undergirds Allison’s model—argues AFRICOM will not view those matters in the abstract, but rather with reference to Africa Command’s ongoing relevancy and status within the broader national security bureaucracy.

As emphasized earlier, this is not to cast aspersions on anyone serving at AFRICOM itself. Miles’ Law is a neutral descriptor of bureaucratic behavior, not a moral judgment. It is simply to acknowledge bureaucratic entities seldom endorse a policy approach that decreases their own importance. In that light, it is perhaps unsurprising that the current commander of AFRICOM recently called for “doubling down” on the U.S. counterterrorism strategy in Africa.74

Related to this, military operations in Africa also would seem to hold greater priority for a dedicated command exclusive to that continent, as opposed to alternate arrangements where the geographic focus is much wider. It is helpful here to consider specific real-world examples where such a command did and did not exist under the Unified Command Plan. Three short case studies follow in which the United States weighed the deployment of ground forces in Africa at different points over the past 50 years. For contrast, one case is drawn from the period when Africa was unassigned in the UCP, a second from when Africa was assigned to adjacent geographic combatant commands, and a third under the existing command arrangement.

Case 1: Angola 1975 (No combatant command)

The ouster of Portuguese dictator Antonio de Oliveira Salazar in 1974 precipitated independence for Portugal’s remaining colonies in Africa and Asia, including Angola. But Angola faced multiple internal forces seeking control of the central government in the wake of independence. Cold War powers backed contending factions, with Cuba and the Soviet Union supporting the Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), while the United States and China supported two other factions, the Front for the National Liberation of Angola (FNLA) and the National Union for Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).75

With Africa unassigned in the UCP at that time, the Joint Staff position was the dominant voice from the uniformed military with respect to policy toward that continent. Throughout the Angolan crisis, General George S. Brown, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, opposed direct U.S. military intervention and did not view Angola as a vital issue for U.S. security.76 One contemporary observer described the Joint Staff position on Angola as “studied indifference.”77

This perspective was in opposition to that held by senior civilian officials within the Ford administration—primarily Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. He considered Angola an important test of U.S. resilience against communist adventurism post-Vietnam.78 Kissinger advocated for a more muscular intervention in the form of surged military aid and the deployment of U.S. military advisers on the ground.79

Over the course of 1975, a third path emerged as the main focus of U.S. policy: the Central Intelligence Agency was instructed to provide covert support to the FNLA and UNITA in the form of funding and weapons transfers.80 In November 1975, Brown raised concerns over the arms shipments, questioning both the technical ability of the FNLA and UNITA to operate advanced U.S. anti-tank missiles and the potential escalatory impact of other systems, such as French plans to send Mirage fighters.81 The following month, Brown further advised President Ford against deploying U.S. warships off the Angolan coast due to the risk of inadvertent escalation, explicitly citing the Gulf of Tonkin as a precedent to be avoided.82 In the end, the United States did not intervene directly with military forces and funding for covert action was suspended by Congress in 1976, ending U.S. involvement in Angola.83

Case 2: Somalia 1992 (adjacent combatant command)

By 1992, Somalia had been suffering under the absence of a functional centralized government, following the 1991 ouster of long-time dictator Mohamed Siad Barre. This abetted a humanitarian crisis in the country, with mass starvation. In an effort to mitigate the situation, the United Nations began delivering food aid but was blocked in some instances by local militias.84 As already noted, the Bush administration opted to employ the U.S. military to deliver and protect aid shipments, beginning in December 1992, in the operation initially known as “Restore Hope.”

This was the first instance since the UCP’s creation where ground forces were deployed in Africa under the direct purview of a geographic combatant command—in this case, Central Command, which held responsibility for the Horn of Africa. The commander of CENTCOM, General Joseph Hoar, approached the mission with great reluctance. He repeatedly strove to emphasize a narrow humanitarian support operation and to avoid entanglement in internal Somali security to the extent possible.85 Hoar successfully protested inclusion of a disarmament mission (i.e., seizing weapons from militias) in the original execution order issued by the Joint Staff.86 “Mission creep” remained a central concern for Hoar throughout the operation.87

Despite Hoar’s reservations, the Somalia operation eventually took on a hard-security component. The U.S. mission was expanded under the Clinton administration in the summer of 1993 to include apprehending a key political-military leader, Mohammed Farah Aidid, and other kinetic action against Somali militias.88 At the time, Hoar expressed pessimism over the specific objective of seizing Aidid—judging there was at best a 25 percent chance of success—and advised against using special operations forces to that end.89 Hoar would eventually relent and an SOF task force with over 400 personnel deployed to Somalia in August 1993, with a goal of capturing Aidid.90

In October 1993, U.S. and UN forces fought Somali militias in the two-day Battle of Mogadishu, in which 18 U.S. military personnel were killed and over 80 wounded.91 U.S. forces would withdraw from Somalia six months later in March 1994.92 Aidid was never captured.

Case 3: Somalia 2022 (dedicated combatant command)

As discussed, U.S. forces have been involved in counterterrorism operations in Somalia since at least 2007. This included a small but ongoing deployment of U.S. troops on the ground, primarily special operations forces. The objective of these operations was to train Somali forces and, in some cases, to directly target al-Shabaab, a terrorist organization affiliated with al-Qaeda.93

By 2020, U.S. forces in Somalia numbered about 700 and were withdrawn by President Trump during the final month of his administration.94 A 16-month period ensued during which there were no U.S. forces permanently based in Somalia, although security cooperation between the United States and Somalia continued, with periodic deployments of U.S. forces into the country from neighboring bases in Djibouti and Kenya. The then-commander of AFRICOM, General Stephen Townsend, referred to this as “commuting to work.”95 In May 2022, the Biden administration reversed the Trump policy, allowing for a permanent redeployment within Somalia.96

During the 16-month interregnum, unidentified senior U.S. military leaders privately argued for a change in the Somalia deployment policy to allow a return to permanent bases.97 Publicly, Townsend emerged as an advocate for reversing the Trump decision, although he was careful to never explicitly call for a permanent reintroduction of U.S. forces while the Biden administration conducted its Somalia policy review. Instead, Townsend emphasized the inefficiency of “commuting to work” and the danger that the transport into and out of Somalia posed to U.S. forces as opposed to fixed, defended bases within the country.98 In congressional testimony, he touted the growth in al-Shabaab’s strength and influence since the departure of U.S. forces.99 Townsend also expressed his personal view that al-Shabaab had the capability to target the U.S. homeland directly, thereby raising the stakes for continued U.S. engagement. Notably, he conceded that view was not widely accepted in the U.S. intelligence community.100

It is worth pointing out that the Trump administration’s decision on Somalia was discordant: it removed U.S. bases while leaving in place the policy of conducting counterterrorism operations in Somalia. As head of AFRICOM, it left Townsend in the position of trying to support that policy with limited physical infrastructure. Still, Townsend opted to lobby for a reintroduction of permanent bases—not a cessation of counterterrorism operations in Somalia, an approach that was also open to him.

Analysis of the case studies

No doubt each man at the focus of the case studies was offering his best military advice as he saw it. But how much did bureaucratic context (where you sit) influence that answer (where you stand)—whether consciously or subconsciously? How much did a dedicated command for Africa matter?

It is hard not to see a pattern: when Africa was either unassigned (Angola 1975) or the African country in question fell under a combatant commander with another geographic focus (Somalia 1992), there was little appetite among the uniformed military for intervention. In fact, in both cases the relevant military officials worked to either prevent deployment of military forces in Africa or to limit the military role so as to avoid a hard-security component. In contrast, when Africa did have a dedicated combatant commander (Somalia 2022), that commander advocated for reestablishing permanent deployments in-country after they had been removed by the previous administration. Moreover, he was successful in doing so.

Certainly, there are limits to this type of analysis. Other factors may be at work beyond command organization. Brown and Hoar both had direct experience with the Vietnam War. That conflict likely influenced their thinking not just about engagement in Africa per se, but involvement in the specific types of conflict represented by the Angolan and Somali civil wars. (Note Brown’s explicit reference to the Gulf of Tonkin, the incident that escalated U.S. military involvement in Vietnam.) In contrast, during the War on Terror, fear of inaction against terror threats often outweighed concerns over the costs of intervention. Ideas about the use of force likely affected the thinking of the military actors in the three cases in addition to command arrangements.101

Yet the impact of command arrangements cannot be entirely discounted. Among other aspects, they help shape specific lenses through which military options in Africa are viewed. In the case of Angola, Brown—as chairman of the Joint Chiefs—was concerned with the global struggle against the Soviet Union; from his perspective, events in a country in southwestern Africa were not essential to that broader competition. With respect to Somalia in 1992, one can speculate Hoar may have been more focused on other concerns within Central Command’s area of responsibility, notably ensuring security of the Persian Gulf oil supplies, arguably CENTCOM’s original raison d’être.

In contrast, Somalia in 2022 was a primary concern for AFRICOM and, indeed, had been an area of focus since the command was activated. Through Africa Command’s specific bureaucratic lens, Somalia mattered a great deal. Under another command arrangement, this might not have been the case. For example, had Africa fallen under European Command’s purview in 2022—at the time of Russia’s mass invasion of Ukraine—would reestablishing bases in Somalia have been an overriding priority for the combatant commander? A command explicitly focused on Africa is more likely to see military missions on that continent as critical, as opposed to command arrangements that afford a wider aperture on U.S. security interests.102

One can posit other interesting counterfactuals. Would the United States have been more likely to intervene in Angola if there had been an Africa Command in 1975? Would such a combatant commander have been a bureaucratic ally of civilian officials, like Kissinger, calling for military intervention? To pose one final question: which of the three command arrangements discussed in the case studies would be most conducive to a shift in U.S. policy away from a counterterrorism lead in Africa now?

Concluding thoughts

The effectiveness of U.S. policy in Africa will remain a source of debate, as will alternate approaches. Moving forward, U.S. command arrangements should increasingly be incorporated into that discussion. If the goal is to eventually reduce the U.S. military lead in African policy, maintaining a dedicated combatant command for the continent makes less sense.

Rescinding AFRICOM’s remit would not be the equivalent of waving a magic wand and singlehandedly fixing U.S. policy. Rather, downgrading Africa’s status within the Unified Command Plan is a first step—but likely a necessary one—in moving toward a more effective, balanced U.S. approach. At a broader level, such a move might also signal the exact opposite of what was intended in 2008—that the United States does not need a military lead to engage seriously with a region of importance like Africa.

To expand on that point, suggesting a dedicated combatant commander for Africa is not required should not be conflated with saying the continent is irrelevant to U.S. interests. Rather, it is to argue the United States does not need a military lead to demonstrate that relevance. It has other options in its national toolkit with which to exert influence.

Consider again the Angolan case: the United States demurred on intervention yet its position in the overall Cold War struggle ultimately was not compromised. To the contrary, Angola slowly sapped communist resources, especially Cuba’s, which deployed over 50,000 troops there to uncertain effect.103 While analogies between the Cold War and the current era are imperfect, they nonetheless suggest military engagement is not always the preferred solution.

That said, a three-star subcommand under EUCOM would still afford the United States a focused commander for planning and implementing military operations as needed. Yet it would remove an important player—an elite four-star combatant commander—in the bureaucratic game that shapes the overall U.S. policy approach in Africa, which currently hues toward a military focus.

The unique relationship between AFRICOM and EUCOM—through which most of their component commands are shared—should enable a smooth transition from the current command arrangement to the proposed three-star subcommand. This is an important point: the forces currently assigned to AFRICOM would still be available—either from EUCOM’s force structure or from SOCOM in the case of special operations personnel—to protect U.S. interests in Africa if required. Military force would still be an option—but not necessarily the leading one.

Derivations of this proposal can also be considered in which responsibility for some African countries (beyond Egypt) reverts to Central Command. Would it be useful to reincorporate the Horn of Africa into CENTCOM in order to place the entire Red Sea littoral under a single commander? Or is it more important to keep a continent-wide focus on Africa under the proposed subcommand under EUCOM?

The specific nuances of alternate command arrangements should be explored and debated, but the core recommendation remains: striking Africa Command as it currently exists from the Unified Command Plan. The United States went for six decades without a dedicated four-star commander for Africa. It should not be afraid to do so again.

Appendix

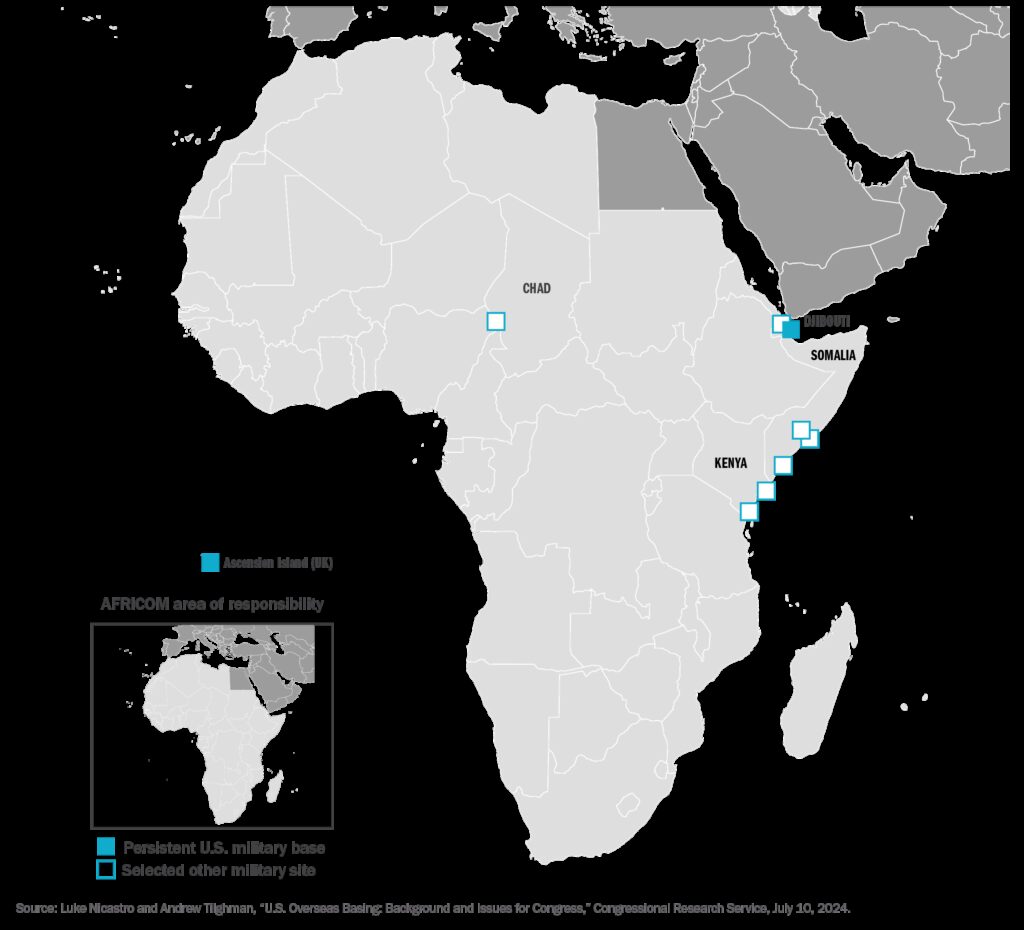

Assessing U.S. basing infrastructure in Africa

In discussing a change in Africa’s status under the Unified Command Plan, it is natural to consider the impact on U.S. basing infrastructure on that continent. As discussed in the main paper, the dual-hatted service component commands which support AFRICOM are all headquartered in Europe, as are the bulk of their forces. But the United States does position some forces directly in Africa itself. Any change in the UCP would not necessarily alter those deployments. However, there may be a desire to reduce presence in accordance with moving away from a military lead in U.S. engagement towards Africa. To that end, this appendix attempts to elucidate the current U.S. footprint in Africa as it can be gleaned through open sources.

The subject of basing in Africa also has added relevance at the moment as the United States was recently asked to leave its two facilities in Niger—one at the capital, Niamey, and a larger installation at Agadez.104 The future of the U.S. presence in Chad is also under review, with some U.S. forces having been requested to depart that country, at least temporarily.105

The language of basing

Parsing the U.S. military infrastructure in Africa is complicated by a few factors. First, there is the specific nomenclature employed by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). It has four main designations for the facilities where it deploys personnel overseas. Listed in descending order of size and infrastructure, these are main operating bases (MOB), forward operating sites (FOS), cooperative security locations (CSL), and contingency locations (CL).106 There is no hard-and-fast rule, but, generally, main operating bases and forward operating sites tend to be publicly acknowledged as bases by DoD, while cooperative security locations and contingency locations are not.

The concept of rotational forces also confuses matters when looking at force levels. These are units which deploy to a given a country on a periodic basis and are thus not considered as permanently stationed there. However, the U.S. presence might be constant even if specific units rotate in and out of a given location. Such accounting peculiarities can create discrepancies between the number of forces the United States actually has on the ground and official reporting by sources such as DoD’s Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC). For example, the 1,100 U.S. troops previously based at Niamey and Agadez were considered “rotational” and did not show up in official DMDC tallies, which listed only 17 active-duty personnel assigned to Niger as of December 2023.107

A final challenge is the lack of official statements on U.S. basing in Africa. AFRICOM delivers a posture statement to Congress annually but these are noticeably lacking in details regarding specific facilities and troop deployments in individual countries.108 In contrast to more established theaters, like Europe and the Pacific, discerning U.S. presence in Africa tends to require more “detective work.”

There have already been a number of useful efforts in this regard, including a study by two geographers at UCLA that relied on government contracting data (among other sources) to piece together a picture of the U.S. basing network in Africa.109 Other important sources include a declassified force posture document from 2019 available on AFRICOM’s website and two declassified maps from the same timeframe, published by the Intercept.110 Some of these sources are slightly dated, but taken together—along with contemporary press reporting and open sources like The Military Balance—they nonetheless provide a good sense of the U.S. military footprint in Africa.111 A recently released Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on U.S. overseas basing is another useful resource.112

Core U.S. facilities in Africa

AFRICOM’s two most important facilities are situated at the eastern and western edges of its area of responsibility—in Djibouti and on Ascension Island.

The United States stations about 4,000 troops in Djibouti, along with one squadron each of MQ-9 Reaper drones, C-130 transport aircraft, and Osprey tiltrotor helicopters.113 Most of these forces are based at Camp Lemonnier, an old French Legion garrison the U.S. has significantly expanded, but drone operations are conducted from a separate facility, Chabelley Airfield.114

AFRICOM appears to have few personnel permanently deployed on Ascension, an island in the South Atlantic, about 950 miles southwest of Liberia. But it is an important conduit for the flow of forces in and out of Africa. A British possession, Ascension is also home to a Royal Air Force base and tracking facilities used by U.S. Space Command.115

AFRICOM’s facilities at Camp Lemonnier and on Ascension Island are the only two installations in its AOR publicly acknowledged as bases.116 That said, the declassified map published by the Intercept showed Africa Command having 29 total facilities in its area of responsibility.117 Likewise, the declassified posture statement from 2019 listed installations in 15 different countries (i.e., 13 beyond Djibouti and the United Kingdom’s Ascension Island).118

All of these additional sites were labeled as either cooperative security locations or contingency locations.119 They are not recognized publicly by DoD nomenclature as bases. And, in truth, many of these facilities may not be that substantial. Some may simply represent an access agreement for periodic use of an airfield, for example. But other sites clearly constitute a significant, ongoing presence, as was the case of the cooperative security location at Agadez, which housed MQ-9 Reaper drones and most of the 1,100 U.S. troops previously deployed in Niger.120

DoD’s basing lexicon and AFRICOM’s public reticence on the subject arguably contribute to the impression the U.S. is concealing a larger military footprint than it likely has on the continent. Greater transparency by DoD and the command on the disposition of its forces might alleviate concern over U.S. presence in Africa rather than exacerbating it. The U.S. clearly has more than two bases in AFRICOM’s area of responsibility, but it also does not have 29 as is sometimes suggested.121

The aforementioned CRS report identified nine U.S. bases in Africa Command’s AOR. This includes Ascension Island, the two sites in Djibouti, three in Somalia, two in Kenya, and a base in Chad whose status is currently under review.122 The CRS assessment might be a useful middle ground for discussions of U.S. presence in Africa moving forward as it appears to capture the most substantive deployments by U.S. forces on that continent while eschewing more transitory sites like contingency locations. But as it is based on open sources, the CRS report still may not be comprehensive.

U.S. drone bases

Throughout AFRICOM’s tenure, the facilities that have drawn the most interest are those where it bases drones. During the command’s existence, the United States has operated unmanned flights from at least eight facilities across the continent.123

Garoua, Cameroon

Ndjamena, Chad

Chabelley Airfield, Djibouti

Arba Minch, Ethiopia

Niamey, Niger

Agadez, Niger

Port Victoria, The Seychelles

Bizerte, TunisiaMany of these sites appear to no longer be operational. The drone bases in Ethiopia and the Seychelles were closed by the mid-2010s.124 The use of drones from Chad seems to have been a one-off instance related to the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping in 2014, rather than an ongoing mission.125 The 2019 posture statement indicated the U.S. presence at Garoua was ending, suggesting that drone site has also ceased operations.126 As previously stated, the United States was recently evicted from the two bases in Niger; prior to that, the United States seemed to consolidate its operations at Agadez (as opposed to Niamey), following the Nigerien military coup in 2023.127

The status of the drone base in Tunisia is uncertain. The site was described as “non-enduring” in the 2019 posture statement, although there has never been an official statement it has closed.128 It is not included on the CRS report map of U.S. basing sites in Africa.129

The United States is also seeking new drone bases on Africa’s west coast to compensate for the loss of facilities in Niger. Candidate sites reportedly include Parakou in Benin, Tamale in Ghana, and three sites in Ivory Coast.130

All told, the current U.S. drone footprint appears less expansive than it once was, with only one site (Chabelley Airfield in Djibouti) that can be confirmed as currently operational—at least from public sources. This also suggests the significance of the ouster from Niger; Agadez might have been one of only two active U.S. drone sites in Africa at the time of eviction.

Uncertain force levels

In terms of the level of U.S. forces deployed in Africa, it is also difficult to be precise. By far the largest concentration is the 4,000 troops in Djibouti. When it approved a return of U.S. bases to Somalia, the Biden administration capped force levels at around 450 troops in that country, giving some sense of current U.S. presence there.131 Combined, that gives a back-of-the-envelope total of 4,450 troops based in those two countries.

But there is still the matter of the various other cooperative security and contingency locations the United States maintains in Africa. How many U.S. forces operate from those sites on a temporary basis at any one time?

That is difficult to say with reliability. The drone base at Agadez appears to have been on the larger side for a cooperative security location, with over a thousand troops. Other cooperative security locations may have only a few hundred military personnel or fewer deployed there at any one time, with far fewer at contingency locations. To take some specific examples, the drone base in Cameroon featured up to 300 personnel while in operation.132 At the time of the 2020 ambush at Manda Bay, Kenya, the United States was believed to have about 200 troops in that country.133 U.S. force levels in Tunisia were estimated at around 150 by the late 2010s.134 The U.S. deployment at Ndjamena, Chad—currently at the center of a diplomatic dispute—is thought to be fewer than 100 soldiers.135

That is just a brief snapshot of some past deployments and exact figures for current operations remain elusive. But these numbers give some general sense of scale in terms of U.S. deployments at cooperative security locations and contingency locations. If one assumes a ballpark figure of two dozen or so additional CSLs and CLs in Africa (beyond sites in Djibouti and Somalia) and 100 to 200 troops at each site, the sum of U.S. forces deployed across those sites can be broadly estimated at about 2,400 to 4,800 troops (and those numbers could very well be high). When added to the 4,450 troops believed to be based in Djibouti and Somalia, AFRICOM likely has fewer than 10,000 troops in its area of responsibility at any one time, perhaps substantially fewer. In the past, AFRICOM itself has cited 6,000 as the number of DoD personnel in its AOR, but has never given a detailed breakdown of that figure in terms of country-specific deployments or types of forces.136

On the one hand, these numbers should not diminish the potential for entanglement posed by U.S. force deployments in Africa. Recall the firefights involving U.S. troops in Kenya, Niger, Tunisia, and elsewhere, as noted in the main paper.

On the other hand, estimated force levels demonstrate scaling back U.S. military operations and presence in Africa might be far easier than in other theaters. For better or worse, the Nigerien base evictions have already gone a long way in this regard.

The future U.S. force posture in Africa

Moving forward, one can look at two levels of debate. First, how much presence does the United States require on the ground in Africa outside the two main access points—Djibouti and Ascension Island? The main focus of such a discussion would be on reducing the various cooperative security locations and contingency locations spread throughout the continent. This would include considering the future of U.S. facilities in Kenya and Somalia and assessing whether the new drone sites are needed on Africa’s west coast.

This isn’t to automatically argue such sites are not required. But it is to suggest basing should be reviewed in the context of any major shift in U.S. policy. Bases ultimately are not an end in themselves, but rather a tool for supporting U.S. interests and goals. If the U.S. policy approach toward Africa does change, the military footprint on the continent should be examined by default to see if it still aligns with the new strategy.

A second level of debate would focus on Djibouti itself. Is the large base at Camp Lemonnier and the drone facility at Chabelley required long-term if the goal is to reduce the prominence of counterterrorism in U.S. engagement with Africa? Withdrawal from Djibouti could underscore that change by returning the United States to its pre-September 11 footprint in Africa (i.e., no major bases). Alternately, retaining the U.S. position in Djibouti might make reduction of the rest of its military footprint in Africa more palatable by preserving a redoubt (along with Ascension Island) from which to expand U.S. presence if the military situation ever warranted.

Until there is a more complete public picture of the U.S. force posture in Africa, however—and until an alternate direction for policy has been officially endorsed—concrete recommendations about the U.S. footprint are difficult to make. The point to emphasize is basing infrastructure should be considered concurrently with command arrangements if a new direction in U.S. policy is to be coherent.

Endnotes

1

See, for example, Paul D. Williams, “Subduing al-Shabaab: The Somalia Model of Counterterrorism and Its Limits,” Washington Quarterly, vol. 41, no. 2 (Summer 2018) 95–111, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2018.1484227; Jason Warner with Julia Broomer, and Stephanie Lizzo, “Assessing U.S. Counterterrorism in Africa, 2001–2021: Summary Document of CTC’s Africa Regional Workshop,” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, U.S. Military Academy, February 4, 2022, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/CTC-Africa-Regional-Workshop-Summary-Document.pdf; Alex Thurston, “An Alternative Approach to U.S. Sahel Policy,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, Quincy Brief no. 32, November 7, 2022, https://quincyinst.org/report/an-alternative-approach-to-u-s-sahel-policy/; Sara Jacobs, “A New U.S. Approach in Africa: Good Governance, Not Guns,” Foreign Policy, December 12, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/12/12/us-counterterrorism-strategy-africa-security-assistance-governance-extremism/; Elizabeth Shackelford and Ethan Kesseler with Emma Sanderson, Less Is More: A New Strategy for U.S. Security Assistance to Africa (Chicago: The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 2023) https://globalaffairs.org/research/report/less-more-new-strategy-us-security-assistance-africa; C. William Walldorf, Jr., “Overreach in Africa: Rethinking U.S. Counterterrorism Strategy,” Defense Priorities, August 31, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/overreach-in-africa; John J. Chin and Haleigh Bartos, “Rethinking U.S. Africa Policy Among Changing Geopolitical Realities,” Texas National Security Review, vol. 7, no. 2 (Spring 2024) 114–132, https://doi.org/10.26153/tsw/52237.

2

Perhaps the most cogent assessment came from a small conference of counterterrorism experts convened at West Point in October 2021. The summary report from that event asserted: “U.S. counterterrorism assistance in Africa between 2001–2021 has been lackluster at best and harmful at worst. The workshop’s discussions underscored that U.S. efforts, in both the kinetic and non-kinetic realms, have tended to be most effective at bringing about short-term operational successes but generally not strategically successful in the long-term. Considering these insufficiencies, participants agreed that a rethink of broader U.S. engagement toward the continent is needed.” See Warner, “Assessing U.S. Counterterrorism in Africa, 2001–2021,” 1.

3

See, in particular, Jacobs, “A New U.S. Approach in Africa”; Shackelford and Ethan, Less Is More; and Chin and Bartos, “Rethinking U.S. Africa Policy Among Changing Geopolitical Realities.”

4

Michael J. Vassalotti, “Defense Primer: Commanding U.S. Military Operations,” Congressional Research Service (IF10542) updated January 12, 2024, 1, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10542/14. See also United States Code, Title 10, Subtitle A, Part I, Chapter Six, § 161, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/161.

5

The seven geographic combatant commands are Africa Command, Central Command, European Command, Indo-Pacific Command, Northern Command, Southern Command, and Space Command. The four functional combatant commands are Cyber Command, Special Operations Command, Strategic Command, and Transportation Command. See Vassalotti, “Commanding U.S. Military Operations,” 2.

6

Edward J. Drea, Ronald H. Cole, Walter S. Poole, James F. Schnabel, Robert J. Watson, and Willard J. Webb, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012 (Washington, DC: Joint History Office, 2013) 9, https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/History/Institutional/Command_Plan.pdf.

7

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 9–20. Note, originally, the Pacific was divided between a Far East Command (with direct responsibility for Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines) and Pacific Command; the two areas of responsibility were consolidated under PACOM in 1956 and Far East Command was abolished.

8

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 44–47.

9

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 3.

10

Prior to STRICOM, Atlantic Command also briefly held responsibility for contingency planning in sub-Saharan Africa from 1961 to 1963. See Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 3–4, 22, 38.

11

The exact composition of EUCOM’s area of responsibility in North Africa varied over time, but usually encompassed at least Morrocco, Tunisia, and Libya, and, later, Algeria. See Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 14, 24, 38, 47.

12

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 51.

13

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 51.

14

At the time of AFRICOM’s creation, PACOM also had responsibility for three African countries—the island nations of Comoros, Madagascar, and Mauritius. See Lauren Ploch, Africa Command: U.S. Strategic Interests and the Role of the U.S. Military in Africa, Congressional Research Service (RL34003) updated July 22, 2011, 4.

15

Daniel L. Haulman, “Crisis in the Congo: Operation NEW TAPE,” in Short of War: Major USAF Contingency Operations, ed., A. Timothy Warnock (Maxwell AFB: Air University Press, 2000) 23–32.

16

For a detailed account, see Fred E. Wagoner, Dragon Rouge: The Rescue of Hostages in the Congo (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 1980) https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA094969.

17

See Michael L. Sevier, Analysis of the United States Airlift to Zaire, May – June 1978 (Maxwell AFB: Air & Command Staff College, 1988) https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA194494.pdf.

18

George H.W. Bush, “Address to the Nation on the Situation in Somalia,” December 4, 1992, George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, accessed July 23, 2024, https://bush41library.tamu.edu/archives/public-papers/5100.

19

For detailed examinations of the U.S. military involvement in Somalia, see United States Forces, Somalia: After Action Report and Historical Overview: The United States Army in Somalia, 1992–1994 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2003) https://history.army.mil/html/documents/somalia/SomaliaAAR.pdf, and Walter S. Poole, The Effort to Save Somalia (Washington, DC: Joint History Office, 2012) https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/History/Monographs/Somalia.pdf.

20

The aid-delivery operation lasted 76 days. For details, see Robert J. Reese, Joint Task Force SUPPORT HOPE: Lessons for Power Projection, (Fort Leavenworth: School of Advanced Military Studies, 1995) https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA301121.pdf.

21

“Where are the Shooters? A History of the Tomahawk in Combat,” Naval History and Heritage Command, April 7, 2017, https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil/Recent/Article-View/Article/2686271/where-are-the-shooters-a-history-of-the-tomahawk-in-combat/.

22

See James G. Antal and R. John Vander Berghe, On Mamba Station: U.S. Marines in West Africa, 1990 to 2003 (Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps History and Museums Division, 2004).

23

Poole, The Effort to Save Somalia, 69.

24

For the sake of completion, the U.S. commitment to the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) should also be noted. Based in the Sinai Desert, the MFO monitors the 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty. Although usually discussed in the context of the Middle East, the force is nevertheless based on African soil. The United States has contributed forces to the MFO since it began operations in 1982 and still has roughly 465 military personnel assigned to it; these fall under Central Command’s purview (which has responsibility for Egypt), not Africa Command’s. U.S. force levels taken from “Chapter Two: North America,” The Military Balance (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2024) 50, https://doi.org/10.1080/04597222.2024.2298597.

25

For example, the United States did not undertake any major military operation in Africa during the 1950s.

26

The United States operated two main military installations in Africa during the Cold War—Wheelus Air Base outside Tripoli and an electronic listening facility in Ethiopia. The U.S. left Wheelus in 1970 shortly after the coup that brought Gaddafi to power in Libya; the listening site in Ethiopia was abandoned in 1975 in the face of rising Eritrean separatism. The U.S. Navy and Strategic Air Command also maintained a series of bases in Morocco from 1950 to 1963. Lastly, in 1980, the Carter administration concluded agreements with Kenya and Somalia for access to ports and airfields in support of U.S. power projection into the Persian Gulf. For additional background, see Walter J. Boyne, “The Years of Wheelus,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, January 1, 2008, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/0108wheelus/; Mark Nixon, “The STONEHOUSE of East Asia,” Cryptologic Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 1 (2019) 29–38; I. William Zartman, “The Moroccan-American Base Negotiations,” Middle East Journal, vol. 18, no. 1 (Winter 1964) 27–40, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4323668; Samuel M. Makinda, “From Quiet Diplomacy to Cold War Politics: Kenya’s Foreign Policy,” Third World Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 2 (April 1983) 300–319, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3991274; and Jeffrey A. Lefebvre, Arms for the Horn: U.S. Security Policy in Ethiopia and Somalia 1953–1991 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991) 197–219, https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.3252846.

27

United States Code, Title 10, Subtitle A, Part I, Chapter Six, § 161.

28

See comments by then-secretary of defense James Mattis in “Pacific Command Change Highlights Growing Importance of Indian Ocean Area,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, May 31, 2018, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1537107/pacific-command-change-highlights-growing-importance-of-indian-ocean-area/.

29

Seth J. Frantzman, “U.S. Central Command Absorbs Israel into its Area of Responsibility,” Defense News, September 7, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/global/mideast-africa/2021/09/07/us-central-command-absorbs-israel-into-its-area-of-responsibility/.

30

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 98–99.

31

Ploch, Africa Command, 1.

32

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 95–96, 99.

33

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 95–96.

34

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 99.

35

“National Security Presidential Directive/NSPD 50,” The White House, September 28, 2006, George W. Bush Presidential Library, accessed August 4, 2024, https://www.georgewbushlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/images//20140324m.pdf. Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 99.

36

Drea et al, History of the Unified Command Plan 1946–2012, 99.

37

“Exploring the U.S. Africa Command and a New Strategic Relationship with Africa,” Statement of Theresa Whelan, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for African Affairs before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Subcommittee on African Affairs, August 1, 2007, 2–3, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/WhelanTestimony070801.pdf. The “J-Structure” or “J-code” is the joint military staff model in which specific aspects of combat operations (e.g., intelligence, logistics, operations, plans) are apportioned to separate departments and designated by a “J” (for “joint”) and a single-digit numeral (e.g., J-1, J-2, J-3, etc.). For additional background, see “The General Staff System: Basic Structure,” Veritas, vol. 7, no 2 (2011) https://arsof-history.org/articles/v7n2_general_staff_system_page_1.html.

38

See, for example, comments by Congressman Christopher Shay in “AFRICOM: Rationales, Roles, and Progress on the Eve of Operations – Part 2,” U.S. House of Representatives, Subcommittee on National Security and Foreign Affairs, Transcript, July 23, 2008, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110hhrg51637/html/CHRG-110hhrg51637.htm. For background on the smart power concept, see Ernest J. Wilson, III, “Hard Power, Soft Power, Smart Power,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 616 (March 2008) 110–124, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25097997. For African perspectives on AFRICOM and smart power, see also Thomas Kwasi Tieku, “The African Union and AFRICOM,” in U.S. Strategy in Africa: AFRICOM, Terrorism and Security Challenges, ed. David J. Francis (New York: Rutledge, 2010) 136–144, and Oluwaseun Tella, “AFRICOM: Hard or Soft Power Initiative?” African Security Review, vol. 25, no. 4 (2016) 393–406, https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2016.1225588.

39

As quoted in Jim Garamone, “Africa Command Unfurls Colors During Pentagon Ceremony,” U.S. Africa Command, October 2, 2008, https://www.africom.mil/article/6321/africa-command-unfurls-colors-during-pentagon-cere.

40

See Christopher S. Chivvis, “Strategic and Political Overview of the Intervention,” in Precision and Purpose: Air Power in the Libyan Civil War, ed. Karl P. Mueller (Santa Monica: The RAND Corporation, 2015) 11–42, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR600/RR676/RAND_RR676.pdf.

41

See Karl. P. Mueller, “Examining the Air Campaign in Libya,” and Deborah C. Kidwell, “The U.S. Experience: Operational,” in Precision and Purpose, 1–10, 107–151.

42

“Civil Conflict in Libya,” Council on Foreign Relations, Global Conflict Tracker, updated July 15, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/civil-war-libya.

43

“ISIS-Libya (ISIS-L),” Counterterrorism Guide, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, accessed August 11, 2024, https://www.dni.gov/nctc/ftos/isis_libya_fto.html.

44

Chart: “Total Strikes and Fatality Estimates, September 2012 – March 15, 2020,” in “The War in Libya,” New America, America’s Counterterrorism Wars, accessed August 9, 2024, https://www.newamerica.org/future-security/reports/americas-counterterrorism-wars/the-war-in-libya/.

45

As quoted in John A. Tirpak, “Lessons from Libya,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, December 1, 2011, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/1211libya/.

46

Tirpak, “Lessons from Libya.”

47

“Directorates and Staff,” U.S. Africa Command, accessed August 14, 2024, https://www.africom.mil/about-the-command/directorates-and-staff.

48

Phil Stewart, “Exclusive – U.S. Discloses Secret Somalia Military Presence, Up to 120 troops,” Reuters, July 2, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-somalia/exclusive-u-s-discloses-secret-somalia-military-presence-up-to-120-troops-idINKBN0F800V20140703.

49

Chart: “Total Strikes and Fatality Estimates,” in “The War in Somalia,” New America, America’s Counterterrorism Wars, accessed August 9, 2024, https://www.newamerica.org/future-security/reports/americas-counterterrorism-wars/the-war-in-somalia.

50

“Federal Government of Somalia Engages Terrorists with Support from U.S. Forces,” U.S. Africa Command, July 29, 2024, https://www.africom.mil/pressrelease/35543/federal-government-of-somalia-engages-terrorists-with-support-from-us-forces.

51

Helene Cooper, “Navy SEAL Who Died in Somalia Was Alongside, Not Behind, Local Forces,” New York Times, May 9, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/09/world/africa/somalia-navy-seal-kyle-milliken.html.

52

It is worth noting that some analysts have question the SNA’s capabilities should support from the U.S. and other external donors be withdrawn. See Paul D. Williams, “The Somali National Army Versus al-Shabaab: A Net Assessment,” CTC Sentinel, vol. 17, no. 4 (April 2024), 42, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CTC-SENTINEL-042024_article-4.pdf.

53

John Hudson, “Biden Mulled Reducing Support for France’s Military Operations in Africa. Instead, He Doubled Down,” Washington Post, January 12, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/us-france-africa-counterterrorism/2022/01/11/2c6c27a2-6d65-11ec-974b-d1c6de8b26b0_story.html.

54

See Nathanial Powell, “Why France Failed,” War on the Rocks, February 21, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/02/why-france-failed-in-mali/, and Benjamin Petrini, “Security in the Sahel and the End of Operation Barkhane,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, September 5, 2022, https://www.iiss.org/en/online-analysis/online-analysis/2022/09/security-in-the-sahel-and-the-end-of-operation-barkhane/.

55

Since 2020, nine African states have experienced the overthrow of the extant leader by the armed forces, with three of these states additionally undergoing “counter coups” and one (Sudan) a triple, counter-counter coup. See “Figure 1: Geographic distribution of coups in Africa in 2020–23” in Chin and Bartos, “Rethinking U.S. Africa Policy Among Changing Geopolitical Realities,” 118. Many of the states in question were not only partners in France’s Operation Barkhane but also members of the U.S. Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership.

56

Rukmini Callimachi, Helene Cooper, Eric Schmitt, Alan Blinder, and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “‘An Endless War’: Why 4 U.S. Soldiers Died in a Remote African Desert,” New York Times, February 20, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/02/17/world/africa/niger-ambush-american-soldiers.html, and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, Eric Schmitt, Charlie Savage, and Helene Cooper, “Chaos as Militants Overran Airfield, Killing 3 Americans in Kenya,” New York Times, January 22, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/22/world/africa/shabab-kenya-terrorism.html.

57

Eric Schmitt, “A Shadowy War’s Newest Front: A Drone Base Rising from Saharan Dust,” New York Times, April 22, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/22/us/politics/drone-base-niger.html.

58

Lilia Blaise, Eric Schmitt, and Carlotta Gall, “Why the U.S. and Tunisia Keep Their Cooperation Secret,” New York Times, March 2, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/02/world/africa/us-tunisia-terrorism.html.

59

Héni Nsaibia, “America Is Quietly Expanding Its War in Tunisia,” National Interest, September 18, 2018, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/middle-east-watch/america-quietly-expanding-its-war-tunisia-31492.

60

Missy Ryan, “U.S. Establishes Libyan Outposts with Eye toward Offensive against Islamic State,” Washington Post, May 12, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/us-establishes-libyan-outposts-with-eye-toward-offensive-against-islamic-state/2016/05/12/11195d32-183c-11e6-9e16-2e5a123aac62_story.html.

61

AFRICOM’s component command are headquartered at Wiesbaden, Germany (Army); Ramstein, Germany (Air Force and Space Force); Stuttgart, Germany (Marine Corps and Special Operations Forces); and Naples, Italy (Navy).

62

Special Operations Forces: Better Data Necessary to Improve Oversight and Address Command and Control Challenges, Report to Congressional Committees, Government Accountability Office (GAO-23-105163) October 2022, 4, 39–42, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-105163.pdf.

63

“Africa’s Security in a Global Context,” Statement of General Michael E. Langley,, Commander, United States Africa Command before the United States Senate Armed Services Committee, March 16, 2023, 18, https://www.africom.mil/document/35173/africom-cleared-fy24-sasc-posture-hearing-16-mar-2023pdf.

64

Active Duty Military Personnel by Rank/Grade and Service, April 30, 2024,” Defense Manpower Data Center, Department of Defense, accessed August 7, 2024, https://dwp.dmdc.osd.mil/dwp/app/dod-data-reports/workforce-reports.

65

Graham Allison and Phillip Zelikow, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: Longman, 1999) Kindle edition. As Christopher M. Jones notes in his entry on bureaucratic politics for the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, Allison’s Model III built on previous work by other scholars including Roger Hilsman, Samuel Huntington, Charles Lindblom, Richard Neustadt, James Rosenau, Warner Schilling, and Richard Snyder, among others, who also explored the nature of bureaucratic actors and their impact on decision-making processes. See the discussion on the intellectual roots of the bureaucratic politics model in Christopher M. Jones, “Bureaucratic Politics and Organizational Process Models,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010) https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.2. For a survey of relevant precursor work on bureaucratic politics, see also Richard C. Snyder, H.W. Bruck, and Burton Sapin, Decision-Making as an Approach to the Study of International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954); Charles E. Lindblom, “The Science of ‘Muddling Through,’” Public Administrative Review, vol. 19, no. 2 (Spring, 1959) 79–88, https://doi.org/10.2307/973677; Richard E. Neustadt, Presidential Power: The Politics of Leadership, (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1960); Samuel P. Huntington, The Common Defense: Strategic Programs in National Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961); Warner R. Schilling, “The H-Bomb Decision: How to Decide without Actually Choosing,” Political Science Quarterly, vol. 76, no. 1 (March 1961) 22–46, https://doi.org/10.2307/2145969; James N. Rosenau, “Pre-Theories and Theories in Foreign Policy,” in Approaches to Comparative and International Politics, ed., R. Barry Farrel (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1966) 27–92; and Roger Hilsman, To Move a Nation: The Politics of Foreign Policy in the Administration of John F. Kennedy (Garden City: Doubleday & Company Inc., 1967).

66

Allison and Zelikow, Essence of Decision, 41–142, Kindle edition.

67

Allison and Zelikow, Essence of Decision, 246–327, 418–523, Kindle edition.

68

Allison and Zelikow, Essence of Decision, 24–31, Kindle edition.

69

Jones, “Bureaucratic Politics and Organizational Process Models,” 2.

70

Rufus E. Miles, Jr., “The Origin and Meaning of Miles’ Law,” Public Administration Review, vol. 38, no. 5 (September/October 1978) 399–403, https://www.jstor.org/stable/975497.

71

Allison and Zelikow, Essence of Decision, 493, Kindle edition.

72

Allison and Zelikow, Essence of Decision, 433–434, 484–486, Kindle edition. The authors also note Alexander George’s contributions in understanding the impact of action channels on bureaucratic outcomes. See Alexander L. George, Presidential Decision-Making in Foreign Policy: The Effective Use of Information and Advice (Boulder: Westview Press, 1980).

73

On the role of the combatant commands in U.S. foreign policy formation, see also Dana Priest, The Mission: Waging War and Keeping Peace with America’s Military (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2003).

74