Abstract: Terrorist organizations are not monolithic entities when it comes to many different aspects of their activities. Among other things, they may change goals, leaders, and tactics over time. This article focuses on one particular type of change: the decision by a terrorist group to geographically expand attack operations outside of its home base of operations. The article presents a discussion of what is meant by expansion and contends that expansion can be best understood in terms of the opportunity and willingness framework. It then turns to an application of this framework to two cases of expansion: the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) into multiple countries.

In 2009, the United States Senate held a pair of hearings over concern that the terrorist group al-Shabaab might pose a threat to the U.S. homeland, even though up until that point, al-Shabaab’s attacks occurred mostly in and around Somalia.1 After the group’s September 2013 attack against a shopping mall in Nairobi, Kenya, policymakers in the United States again expressed increasing concern that the group may turn its sights toward conducting attacks on the homeland of the United States. A few weeks after the attack, the Foreign Affairs Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives held a hearing titled, “Al-Shabaab: How Great A Threat?”2 A few years later, on February 21, 2015, the concern of al-Shabaab expanding its reach from East Africa to the United States resurfaced when the group released a propaganda video calling for attacks on American and Canadian shopping malls.3 Over the next several years, al-Shabaab carried out attacks against U.S. targets in and around Somalia, including the Camp Simba attack in Kenya in January 2020 that resulted in the deaths of three U.S. military personnel.4 The group also directed at least two individuals to obtain flight training in preparation for operations in the United States similar to the September 11 attacks, although both were arrested in countries outside of the United States before those plots could be carried out.5 Despite the concern of policymakers and the efforts of the group itself, at the time of this writing in November 2024, al-Shabaab cannot claim a successful attack on the U.S. homeland.

Even though al-Shabaab has not carried out the attack in the U.S. homeland that many feared, the underlying question that drove the public hearings and continued concern remains an important one: What are the factors that drive some groups to expand their geographic reach and others to remain more locally focused? The importance of this question is even greater in today’s environment in which a large number of terrorist groups remain committed to the use of violence against non-combatants in furtherance of political goals at the same time that many governments have decreased the resources available for counterterrorism.6 The continued conflict in the Middle East, the disruption of recent terror plots in Europe over the past two years, and ISK’s attack in Moscow in early 2024 have only served to underscore the reality of the threat.7

This article endeavors to provide a framework for analyzing the factors that lead to terrorist group expansion. The goal is not to provide a mechanism for perfect prediction—the factors impacting each terrorist group are too unique for this—but rather to offer increased structure to our understanding on this important question. It does so by first contextualizing the concept of expansion across two variables: the distance of the operation from the group’s base and the amount of control the group has over the operation. Then, in seeking to explain why groups choose to expand, it utilizes the opportunity and willingness framework from the literature on international conflict. This framework is then briefly applied in two cases: the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) expansion into India and Islamic State Khorasan’s (ISK) operational expansion into a number of theaters. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications of this for academics, policymakers, and practitioners.

What Is Expansion?

Although it may seem elementary, it is critical to first pause and consider what is meant by expansion. As it turns out, the term ‘expansion’ could be defined along several parameters. A terror group located in one state that takes advantage of the porous, hard-to-defend borders of a neighboring state to establish a safe haven may have expanded its area of operations, as was the case with al-Qa`ida and the Taliban in Pakistan in the time after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 or the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in Venezuela at various points over the history of that conflict.8 In a similar manner, the establishment of logistical supply routes or financial activities in distant countries might also be considered expansion, such as the activities of Hezbollah to raise funds or procure weapons in the United States.9 Another way to answer this question would be to focus exclusively on the interests of a specific country. For example, a U.S.-centric answer to this question might simply focus on the possibility that a terrorist group can strike the U.S. homeland, but this view does not adequately consider the various avenues through which terrorist groups can threaten both U.S. and global security interests as their ability to attack outside of their normal area of operations increases. Another answer might emphasize expansion in terms of an escalating level of attacks from soft to hard targets (or vice versa) or the targeting by the group in its home territory or a foreign country’s governmental or commercial facilities.

In sum, there is no single way to conceptualize ‘expansion.’ However, it is critical to select an approach to ‘expansion’ that captures the dynamic relevant to the analysis of interest. In the case of this article, the concern is with the ability of terrorist groups to conduct attacks across greater geographic distances. More specifically, an expansion involves a group carrying out operations beyond the theater of normal operation. Context is critical in making this determination, as a theater of operation might be a single country (or part of a country) for some groups, while for other it spans across several countries. Moreover, there is also a difference between expansion to the next state over as opposed to expansion that requires a group to cross many borders or even the ocean. The decision to focus on geography is made in part because one of the most dangerous capabilities posed by terrorist groups is their ability to intentionally carry out destructive acts of violence. Although the ability of terrorist operatives to cross borders in order to recruit, raise funds, or obtain weapons might be important conditions enabling violence, they are not the end or primary concern of interest here.

One additional conceptual issue to consider is whether a group should be considered as having ‘expanded’ because its ideology inspired someone in a distant country to carry out an attack, even though there may not have been any direct command-and-control exercised by the group over the operation itself. For example, when a 16-year old teenager in Las Vegas, Nevada, was arrested by authorities in November 2023, information was found in his possession that indicated that he supported Islamic State and referred to “Islamic State – Las Vegas Province.”10 At the time of this writing, no public evidence has emerged to suggest that the teenager communicated directly with or was personally directed by any other formal element of the group. Even if the plot had been successful, would it have been reasonable to say that Islamic State’s operations “expanded” to Las Vegas? It is not clear that the answer to this counterfactual is no, but it also seems that there is a qualitative difference between a group providing inspiration for a plot as opposed to enabling it through the provision of instructions, funding, and so forth or exercising command and control over its execution.a A conclusive answer to this question is not provided here, but it merits additional thought and research.

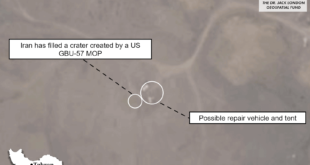

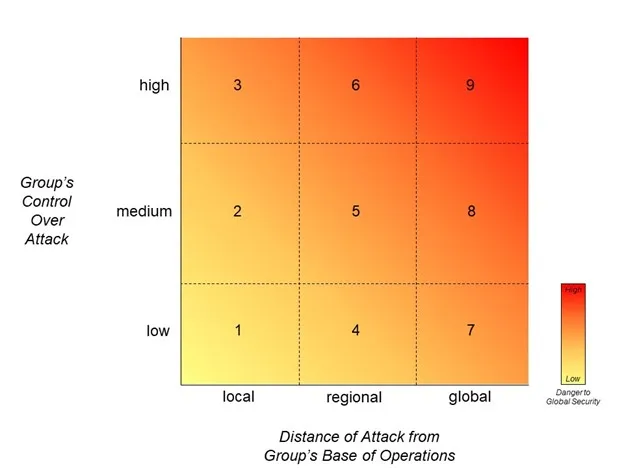

The framework proposed here focuses on attacks as the primary outcome of interest and considers expansion as occurring along two different dimensions: the control that a terrorist group exerts over attacks and the distance of the attacks from the home location of the terrorist group.b Although each of these dimensions exists along a continuum, for the ease of presentation and discussion, Figure 1 depicts each with three separate values or categories. It also contains shaded coloring that accounts for the way in which groups that expand toward the upper-right of the figure represent a greater danger to global security.

Although expansion is a dynamic phenomenon whereby a group moves from one box to another, it may be beneficial for contextual understanding to provide a few examples of the types of attacks that fall into some of the categories that appear in Figure 1.

Categories 1-3 reflect a terrorist group of varying strength and capacity that has mostly local concerns, also referred to as a domestic terrorist group. Even though this group is local, it is important to note that it might be able to inspire others to carry out violence in service of its worldview, but without much direct involvement of the group itself (Category 1). It may also be the case that the group has the capability and control to be able to plan and execute local attacks on its own (Category 3). Groups with the capability to carry out local attacks may indeed pose a serious threat to the government or area in which they operate. And there is a potential that they may, at some point, turn their gaze outward toward an expansion of attacks. However, when it comes to a global threat picture, it is the groups that are capable of both launching and inspiring regional and global attacks that generally create larger international security concerns.

Perhaps one of the most challenging type of groups are those with an attack portfolio somewhere in Categories 4-6, with the most concern for international security focused on Category 6. Some of the groups that carry out attacks in these categories have some level of capability and likely have some measure of staying power, yet they have not continued to expand their operations. Al-Shabaab, discussed in the opening to this article, is an excellent example of a group that falls into Category 6. It has demonstrated strong control over attacks both locally and regionally, and it continues to exist despite persistent international efforts to reduce its area of operations.11 It is these groups in many cases that may pose the most perplexing challenges for security professionals, as they may appear to be on the cusp of expanding.

At the highest end of the threat spectrum is a group that is able to plan and execute a global attack directly (Category 9). Such a group would likely be well-resourced and experienced in the array of tradecraft necessary to carry out such operations. This is a terrorist group that likely poses a direct threat to many nations. Perhaps one of the most well-known examples of this type of attack is al-Qa`ida’s 9/11 attacks in the United States, which demonstrated both a high level of control as well as distance from the group’s known base of operations in Afghanistan.

A group’s attack portfolio does not have to be constrained to one box alone, but may end up conducting operations across multiple categories in a given period of time. One example of this is the Islamic State in the 2015-2017 timeframe. Not only did the group exercise a high level of control over the attack in Paris (November 2015),12 but its ideology also inspired the attacks in Barcelona (August 2017),13 with little evidence emerging to suggest a more central role by the group in the planning or execution of that attack. Of course, during this period of time, the group carried out and inspired attacks in its home base of Iraq and Syria, but also in other locations around the world.14 All of these attacks place the Islamic State’s overall attack portfolio into a number of these categories depending on the specific moment at which the analysis occurs.

So, what then is meant by expansion? Based on the conceptualization presented in Figure 1, expansion can be best thought of as movement by a group horizontally or diagonally from the left to the right. In the former case, a group moving from Category 6 to 9 is expanding, while in the latter case a group moving from 6 to 7 would also be considered expanding. In more straightforward terms, when a group moves from carrying out operations locally to regionally to globally, it is expanding. That is the general type of expansion considered in this article. It is worth noting, however, one might also consider expansion have occurred if a group moves vertically (from the bottom to the top) in terms of their attack portfolio. This would not be geographic expansion, but more an expansion of operational control and capacity. However, this type of expansion is not discussed in this article.

Explaining Expansion

With a clearer understanding of what this article means when it refers to the expansion of terrorist groups, it now turns to address the important question regarding why these groups expand. To do so, it borrows from the literature on international conflict. In this literature, explanations regarding why nations go to war abound. While there are many useful explanations and frameworks for this purpose, some early research focused on the importance of opportunity and willingness to explain state decisions to go to war.15 The idea is relatively straightforward. If a nation is going to go to war against another nation, a state seeking conflict must actually have the opportunity to do so. If two states never interact, it is unlikely they will go to war. If one state has no tanks or soldiers, it is unlikely that it will go to war with another that does. Moreover, opportunity is not sufficient. War will only occur if the state also has the desire, or willingness, to begin fighting. There must be some motivation on the part of the country’s executive, legislature, military, or people to want to engage in combat.

A similar framework can be useful for thinking about the expansion of terrorist groups.c Just like the leadership in other organizations, the decision makers in terrorist groups have incentives for various courses of action but are also bound by constraints.d Decisions about where, when, and how to carry out attacks are not detached from considerations related to the opportunity to carry out such strikes and the willingness to do so given the group’s motivations and goals. Terrorist organizations must navigate and balance factors such as the availability of operatives, the ability of operatives to travel using false documents or safehouses, leadership opinions regarding both the viability and desirability of expansion, and the potential response of the intended target with their overall objectives and goals.

The use of the word “balance” above deserves added discussion. Opportunity and willingness are not to be considered in isolation when attempted to explain expansion. A group may have all the opportunity in the world, but absent a motivation to mobilize that opportunity into an expanded pattern of attacks, the group itself will likely remain locally focused. On the other hand, a group may wish to carry out a worldwide campaign of violence in an effort to advance its political goals, but may not have the opportunity or willingness to do so. A lack of either factor will lead to an outcome in which a group is unable to carry out an expansion in terms of its attack portfolio.

One additional observation has to do with the use of the opportunity and willingness framework as opposed to a seemingly similar framework: capabilities and intent. Some may argue that the difference between these two frameworks is negligible, but the author prefers the former for three reasons. First, as it applies to “opportunity” as opposed to “capabilities,” the author finds the latter term to be narrower and encourage a focus strictly on more tangible resources such as weapons and money. The reality is that the decision to expand is about more than just items. As will be discussed more below, it is also about intangible factors that may be beyond the group’s control that create the space for expansion to occur. Focusing only on “capabilities” may lead scholars and analysts to miss critical factors. Second, although “intent” is not as limiting in the author’s view as “capabilities,” it conveys a level of agency and calculation that might overemphasize leadership choice at the expense of broader environmental factors at play. Intent also seems difficult to assess, relying more on the internal processes of individual thought-making rather than other observable factors.

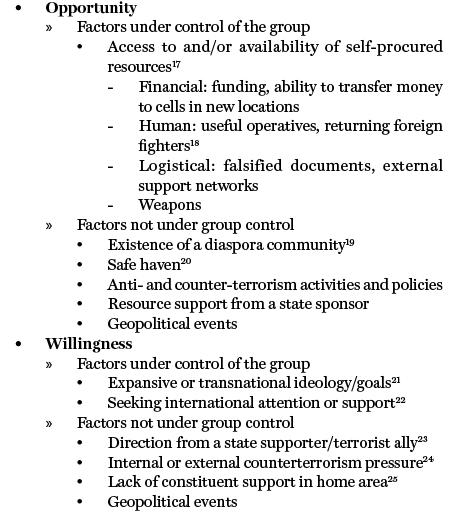

Although terrorist organizations differ from states in many respects, the overarching framework in which they make decisions at times displays similar rationales.16 Space here does not permit a full examination of the reasons identified by scholars that impact decision-making by terrorist organizations, but some of this work, together with other factors necessary for expansion, can be modified and distilled down into factors that fall under the opportunity and willingness framework described above. What appears below is a simple categorization of the factors that might fall under opportunity and willingness when considering the organizational decision to expand.

This list of factors provides some possibilities when it comes to reasons for expansion, but is not intended to be an exhaustive explanation for each case. As noted above, it is critical to state that even if a factor is listed twice (state sponsorship and geopolitical events), this does not mean that the same mechanism is at play. For example, consider the October 7 attack on Israel and the subsequent Israeli response. Some analysts have noted that it has provided a boost to terrorists when it comes to human resources. One senior U.S. intelligence official noted that October 7 “was, is and will be a generational event that terrorist organizations in the Middle East and around the world use as a recruiting opportunity.”26 But in addition to helping the opportunity side of the equation, it may also be the case that October 7 and subsequent events have also encouraged terrorist groups to increase their willingness to target Israel and those viewed as being supportive of it.27 One scholar noted that, “A U.S. military confrontation with Hezbollah could spark terrorist attacks on American targets abroad and domestically.”28 In other words, it might increase the willingness of Hezbollah to act.

Most terrorism experts are familiar with the fact that there is no individual profile when it comes to an individual’s radicalization pathway. The same logic applies here. There is no one-size-fits-all solution or explanation for the reason a group chooses to expand its area of operations. Despite this, the opportunity and willingness framework can still be useful in understanding and structuring an examination of the decision to expand. Although each individual case might deserve its own article or book length treatment, a few brief examples are useful for illustrating the framework in action.

The Expansion of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) to India

In 1983, after years of acrimony between the Sinhalese majority and Tamil minority in Sri Lanka, frustrations exploded into a full-blown civil war between the Sri Lankan government and a number of non-state militant groups. One of these was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, also known as the Tamil Tigers or LTTE. The LTTE’s violence against both government and civilian targets included a wide array of tactics, including suicide bombings.29 Eventually, the group’s nearly 40-year reign of violence ended in 2009 when the Sri Lankan government claimed victory after an intense military campaign, but not until tens of thousands were dead, wounded, or otherwise unaccounted for.30

During the LTTE’s history, there is an interesting transition that happens during the conflict. Using the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) from the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, the first attributed incident for the LTTE is in 1975 in Sri Lanka.31 The GTD reports 279 LTTE attacks up through 1990, all occurring in Sri Lanka. But then, something changes. In 1990, 1991, and 1992, the GTD contains a total of five attacks carried out by the LTTE in India. Looking at Figure 1, it seems that the LTTE changed from being a well-coordinated, locally operating group (Category 3) to a well-coordinated, regionally operating group (Category 6). How do we explain the decision by the LTTE to expand the geographic area of its operations to India in 1990? The opportunity and willingness framework provides a template for doing so.

Opportunity

In terms of opportunity, geographic proximity certainly seems to have made expansion easier in the case of the LTTE, if not likely. The two countries are, at their closest point, merely 25-35 miles away from each other, albeit separated by a body of water.e When it comes to India specifically, there was and is a fairly large population of Sri Lankan Tamils living there, to say nothing of the broader population of Tamil Nadu.32 The close geographic and ethnic ties might have provided some of the opportunity for expansion, although such factors exist in many different contexts, so it is hard to ascribe too much weight to them.

That said, the LTTE arguably had a safe haven in Sri Lanka in which they could plan to expand their portfolio of attacks. Even though they were under pressure from the very beginning of the conflict by the Sri Lankan military, those military efforts had decidedly mixed results at best.33 And even if the northeastern part of Sri Lanka had not been a safe haven, not far away LTTE fighters were trained in India to fight against the Sri Lankan government—an irony given that LTEE would eventually embark on a regional expansion of operations against India.34 In essence, LTTE had benefit of the resources and knowledge of a state sponsor (an important consideration on the opportunities side of the equation) and then later expanded its operations against that very state sponsor.35 Additionally, some analysts have argued that LTTE did not attract significant international censure early on in its operations.36 Moreover, refugees fleeing the violence in Sri Lanka have helped establish a worldwide diaspora community that enabled fundraising and political support from abroad, although this was more limited earlier on.37

The LTTE also seems to have had healthy amounts of resources in order to coordinate, finance, and staff an expansion. On the financial front, it is harder to pin down the yearly earnings of the group. Some estimates have suggested, however, that the group brought in large amounts of money every year, ranging from tens to even possibly hundreds of millions of dollars each year.38 Regardless of the actual amounts, it is clear that financial constraints to an expansion did not seem to exist. And the group had significant human capital as well, with an estimated 10,000 fighters at the pinnacle of its power.39

In sum, it seems that the LTTE had proximity, some level of safe haven, and a sufficient amount of resources working in its favor as far as the opportunity component necessary for expansion. However, as noted above, opportunity in and of itself is not a sufficient explanation. It must be considering in tandem with the willingness factor.

Willingness

Examining the ideology of the group, in this case, does not appear in and of itself provide any added impetus for expansion. The LTTE was largely a secular group oriented toward fighting for the independence of the Tamil minority living in Sri Lanka, in other words, for a geographic homeland on the island of Sri Lanka.40 Of course, the fact that the group was willing to carry out acts of violence in this effort certainly showed a strong resolve to do whatever was necessary for the cause. However, the key point is that, absent either a change in the group’s ideology or some other factor, the willingness to engage in an operational expansion remained low.

Nor does a loss of public support seem a useful explanation. As other scholars have noted, early on the conflict, the LTTE not only managed to eliminate rivals for leadership of the Tamil cause, but also seemed to enjoy some level of public support among Tamils, especially because of the group’s tactical successes and ability to provide some level of protection to population.41 Whether this “support” came by virtue of the LTTE being the only player left on the field or true belief in the group’s goals, ultimately it does not seem to be a factor in explaining the group’s expansion to India.

What more likely explains the expansion of LTTE’s terrorist attacks into India is the introduction of Indian peacekeeping forces into Sri Lanka in July 1987 under the leadership of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Ghandi. These troops, known as the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF), entered Sri Lanka as part of an effort to reduce the violence between the Tamil minority and the Sri Lankan government following the conclusion of the Indo-Sri Lankan Accord. The reasons for the IPKF’s deployment are many, but here it is sufficient to highlight the intended purpose of disarming Tamil militants and ensuring the separation of the warring sides. Soon after its arrival, however, the IPKF found itself targeted by an LTTE that had not been fully supportive of the accords and that felt the IPKF either never had or had lost its impartiality.42 Violence between the IPKF and the LTTE escalated, and eventually the IPKF withdrew in 1990.43

There is dispute over whether the LTTE ever really supported the peace agreement and introduction of the IPKF. Regardless, it is clear that the LTTE came very quickly to view the IPKF as ineffective, biased, and ultimately a roadblock to the LTTE’s objectives. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that part of the LTTE’s operational expansion included deploying a suicide bomber to assassinate former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi at a campaign event in southeastern India in May 1991.44 One scholar observed that the LTTE’s feelings for India and Ghandi were shown most comprehensively in a propaganda publication called The Satanic Force, which highlighted what the group saw as the shortcomings of the IPKF.45

In the end, it seems that the best explanation for the regional expansion of the LTTE’s attack profile is the implementation of counterterrorism/counterinsurgency efforts of the IPKF. Regardless of their legitimacy or shortcomings, the LTTE and its leadership clearly saw India generally, and Gandhi specifically, as an adversary for which a greater response was merited. The decision to expand appears to have been taken, not because the LTTE’s ideology or worldview had changed in any substantive way, but rather because India’s actions brought it into greater conflict with the LTTE. Hindsight prediction is far easier than in the moment prediction, but it does seem that there was escalating rhetoric on the part of LTTE regarding frustration and enmity toward Indian involvement in Sri Lanka that signaled a desire on the part of the LTTE to expand their operations.

Examining the case of the LTTE using the opportunity and willingness framework demonstrated that the willingness piece of the equation was critical for understanding expansion. Although more historical than current, one benefit of discussing the LTTE case is that there is a fair amount of information available in the public space given that the incidents described here occurred more nearly 30 years ago. A more relevant, but also more challenging, example in which this framework might be applied is the case of Islamic State Khorasan (ISK).

The Expansion of Islamic State Khorasan (ISK)

When the group known as the Islamic State declared itself the legitimate (at least in its own view) caliphate in June 2014, it also called for pledges of allegiance of individuals and groups from around the world.46 Within short order, individuals and small parts of other groups around the world began to align themselves with the Islamic State. This included terror threat networks in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Although the Islamic State’s central group did not immediately acknowledge an official branch of its group in the region following the initial pledges of allegiance, it did not take long for official recognition to come. In January 2015, the Islamic State’s official spokesperson released an audio recording in which he formalized the establishment of a province in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, known as Islamic State Khorasan,f or ISK.47 Since that point, ISK has carried out a large number of operations, but according to the GTD, all of its initial operations were within the group’s geographic home base of operations: Afghanistan and Pakistan.48

Pinpointing the exact moment that ISK expanded its operations is not straightforward. According to the GTD, a series of attacks connected to ISK outside of Afghanistan and Pakistan occurred in India in 2017.g Regardless of the specific timing or location, it is clear that the group began conducting operations outside of its home area on or around this time, with plots and attacks turning up in several locations over the next several years, including India, Iran, Maldives, Qatar, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Activity in these particular locations, if conducted with centralized direction from the leadership of ISK or the central Islamic State core group, would qualify as expansion from local (Category 3) to regional (Category 6).

Not too long after these regional plots started to pick up, ISK was also implicated in carrying out attacks and plots in a number of countries outside of the regional sphere, including Austria, France, Germany, Turkey, and Russia.49 In 2020, the Islamic State and possibly ISK may have been involved in the plot to bomb U.S. military bases in Germany.50 Its largest attack during this phase, on March 22, 2024, against the Crocus City Hall in Moscow, killed nearly 150 people and wounded 551.51 This attack, which demonstrated that ISK could carry out attacks far from its home base with high levels of coordination, was an example of global expansion (Category 9).

While the LTTE’s expansion from one country to the next was easier to understand, ISK’s expansion to a wide array of both regional and global targets is a bit more complicated. One approach would be to offer a nuanced analysis of each new country of expansion. While there may be similar factors in the opportunity/willingness framework that help explain the group’s decision to carry out attacks in each of these countries, there are also likely some differences. Another approach, implemented here, is to discuss more generally about how the opportunity/willingness framework might be useful in explaining the overall phenomenon of expansion as it applies to ISK.

Opportunity

On the opportunities side of the framework, the availability of human resources is always an important factor to consider. The Islamic State benefited from an international appeal that allowed it to attract individuals from a wide array of countries around the world, enabling expansion should the group so choose.52 Although ISK’s appeal is not as broad, several of the recent high-profile ISK attacks and plots have highlighted the presence of a number of individuals with Central Asian heritage, especially Tajikistan, including the attacks in Moscow and a recent investigation that resulted in the arrest of eight Tajiks in the United States.53 Their presence in ISK attacks and plots makes sense, as some reporting has suggested that as many as half of ISK’s members are from Tajikistan.54 The presence of a large number of recruits from one country does not necessarily explain the expansionary push, but it does enable it in terms of manpower.

The fact that the eight Tajik men arrested in the United States had claimed asylum at the border highlights how ISK has potentially been exploiting the global migration crisis. Political instability, economic challenges, and conflict have forced many people to flee from their homes and seek refuge abroad. A 2024 UNHCR report showed that, in 2023, the number of people worldwide who had been forcibly displaced from their homes grew to 117.3 million, up from just under 60 million in 2014.55 The number of asylum seekers grew from 1.2 million in 2014 to 6.9 million in 2023.56 To be very clear, the point is not that asylum seekers and refugees are all potential terrorists. Rather, it is that terrorist organizations can take advantage of the flow of humans as an opportunity to move operatives, should they so desire.h After the ISK attack on Moscow, at least one analyst encouraged greater concern regarding the migrant flows from Tajikistan into Russia.57 And, in addition to the eight men arrested at the U.S. border in 2024 mentioned above, an earlier plot in Germany in 2020 also highlighted the way in which the Islamic State (and possibly ISK) might have exploited human migration flows.58

Another point that is clearly an opportunity factor in the ISK case that did not exist for the LTTE in the early 1990s is the prevalence of easy to use, secure, widely available communications technologies that enable groups to coordinate much more easily with operatives in the field. A number of scholars have noted the existence of a multi-tiered structure used by a small number of groups, including ISK, to direct, guide, and inspire attacks from abroad.59 These approaches, such as the failed effort of a Toronto man to carry out an attack on behalf of ISK, involve encrypted channels, online chat groups, and other similar venues.60

A related point is that technological advances have not only facilitated a greater ability of groups to communicate, but also to raise and transfer funds necessary to carry out attacks. Now, instead of relying on traditional bank transfers or the less formal hawala system, money can be sent to operatives abroad in order to carry out attacks. ISK, among other groups, has certainly taken advantage of various financial platforms for financing purposes.61 Although there remains much uncertainty surrounding the Moscow attack, some information suggests that ISK used cryptocurrency to transfer money to the perpetrators.62

Finally, it is important to note that ISK’s expansion of attacks in the past few years has coincided with a decreased amount of counterterrorism pressure against the group.63 Not only did U.S. and other international troops withdraw from Afghanistan in August 2021, but many critical intelligence resources that accompanied them diminished as well.64 In place of resources on the ground, U.S. security and intelligence officials have articulated an ability to transition to an “over-the-horizon” counterterrorism capability.65 However, this capability has some notable challenges that have only increased in scrutiny.66 According to U.S. Central Command Commander General Michael Kurilla, “lack of sustained pressure allowed ISIS-K to regenerate and harden their networks.”67

Not only did a reduction in U.S. pressure in Afghanistan potentially increase the opportunity of ISK, but it appears that so too did a lack of counterterrorism capability (or, at the least, a perception of such) among some of the nations that were ultimately targeted by ISK. In the case of the attacks against both Iran and Russia in 2024, it was later revealed that U.S. intelligence had previously warned both countries of potential ISK attacks, but that those warnings were not effectively acted upon.68

When it comes to opportunity, the above discussion does seem to indicate that there has been sufficient opportunity for ISK to expand. And although that opportunity appears to have increased after the U.S. withdrawal in 2021, there were certainly indicators of increasing opportunity prior to that point.

Willingness

Shifting to an analysis of the willingness side of the framework, there are several contributing factors. First, the Islamic State itself has an expansionary ideology, both in terms of geography and the need to attack adversaries who oppose it. In its propaganda, the group focused on painting the nations of the world as legitimate targets, not only for attacks but also for conquering.69 As an affiliate of the parent organization, ISK has, on some level, the same worldview in its DNA.70 Of course, it is important to understand that the group is not a monolith, and the impact of these forces can differ from time to time.71 Nevertheless, there is nothing constraining external expansion of operations in the group’s ideology. Absent this feature, ISK might be more like a more nationally focused group such as the Taliban.72 But with a worldwide and expansionary ideology, theoretically the willingness of the group to strike abroad has existed from the beginning of the organization. Given that, it is hard to suggest that the increasing number of regional and global attacks can be attributed totally to ideology. Another way to think about it is that the ideology of ISK does contribute to its willingness to conduct an expansion, but it does not really help explain the timing of that expansion.

Another factor in the willingness part of the equation may be ISK’s desire for payback, either for the oppression of Muslims around the world and/or the more targeted counter-Islamic State efforts of nations around the world. On this latter front in particular, there seem to be plenty of threats levied by the Islamic State and ISK against a wide range of enemies. The Global Coalition Against Daesh has 87 members, not to mention those outside of the coalition who have fought against the Islamic State. This makes assigning the reason for ISK’s expansion on a desire for revenge against nations that have fought against the group seem a bit unfulfilling, although it would also be hard to argue that participation in activities against the Islamic State (either in the past or currently) does not raise the risk to some degree.73 Consider two examples from Moscow and Iran.

In the wake of the Moscow attack, Russia’s history of abuses against Muslims in Chechnya and its support of the Assad regime in Syria were both mentioned in news reporting as potential reasons for ISK’s focus on the country.74 But, as early as 2015, Russia had also previously fallen into the crosshairs of the Islamic State (ISK’s parent organization) because of its involvement in the Syrian civil war, with the downing of a Russian airline in the Sinai Peninsula and several small-scale inspired attacks in Russia.75 More recently, ISK has gone after Russia in its propaganda because of Russia’s support for the Taliban.76 This rationale also likely played a role in a suicide bombing attack on the Russian embassy in Kabul in September 2022.77 In the group’s Voice of Khurasan publication issued in April 2023, one article attempted to redirect violence from the Russia-Ukraine conflict toward Russian troops fighting against Muslims around the world and in Russia.78

Iran’s historical involvement in Syria led it to deploy military forces earlier in the Syrian conflict. That fact, combined with the Islamic State’s hatred of Shi`a adherents, led to Iran being a target of Islamic State propaganda, with efforts being made by the group to offer Persian translations of its material.79 It is not known exactly when the baton was passed from Islamic State core to ISK, but by late 2022, both the Islamic State and the Iranian government reported the involvement of Afghans, Azeris, Tajiks, and Uzbeks in attacks and plots, followed by the claim of an arrest of a key ISK leader in Iran in May 2024.80 Then, in January 2024, after ISK attacked a funeral in Iran for Qassem Soleimani, largely seen as the architect of Iran’s involvement in Syrian civil war, one rationale given by observers in the press was that the attack was retribution for the Soleimani’s role in that campaign.81 Given its consistent messaging and efforts, it seems clear that ISK had been increasingly targeting Iran for years in some part for that reason.

Although ISK’s expansion of operations outside its normal operating territory pre-dates the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, there does seem to be a connection between its increased expansion of operations and the presence of a new ruler in the Taliban. Several scholars suggested that the group’s willingness to expand operations may be due to ISK’s desire to maintain relevance as it weathers the Taliban’s efforts to destroy it.82 It is worth noting that these efforts to destroy ISK have proven to be unsuccessful, even if there have been some successes by the Taliban.83 Another suggestion is that ISK’s willingness to expand may also reflect an effort to embarrass the Taliban by showing that it cannot prevent transnational attacks from emanating from Afghanistan.84 In other words, regardless of whether the motivation to expand is due to one, or a combination, of these arguments, the Taliban in charge does seem to have provided some accelerant to the geographic expansion of ISK attacks.

This brief examination of some of the willingness factors has suggested that there were both longstanding and recently emerging forces at play when it comes to ISK’s expansion. On one hand, the group’s adherence to Islamic State ideology provided a broad set of potential targets and adversaries. On the other hand, the recent departure of the United States left ISK as one of the primary actors still in opposition to the Taliban, a fact which may have altered its strategic calculus. Given the recency of ISK’s expansion, it may be the case that more information will emerge that helps provide a clearer picture of its expansion efforts and helps apportion the weight that should be given to each of these factors.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to provide a simple framework while exploring the rationales that might help explain why terrorist organizations expand the geographic scope of their attacks. In doing so, it posited that expansion requires a combination of both opportunity and willingness factors. These two factors are not linear, as, for example, a group may possess the desire but be hamstrung by a lack of adequate resources. It may also be the case that a well-funded, large terrorist organization does not expand because it has no motivation or reason to do so. Expansion is not inevitable or desired by all groups, which is part of what makes this line of inquiry important.

This article also applied the opportunity and willingness framework in the context of two cases: the LTTE and ISK. Neither of these two brief case studies in this article should be considered exhaustive in terms of the evidence or authoritative in capturing the reasons for expansion. However, the point remains that the opportunities/willingness framework can be useful for categorizing the factors leading to expansion after the fact, but may also prove useful for purposes of ex-ante analysis. As policymakers and practitioners seek to understand the threat environment, studying the factors that groups have in both the opportunity and willingness categories may potentially provide indicators and warnings, tripwires, and other useful information in understanding the expansion process.

Admittedly, this article has been a short treatment of a complicated subject, about which additional research can and should be conducted. Such research might profitably add more substance to the opportunity and willingness framework outlined above, teasing out the factors that matter as opposed to those that do not seem to matter. Another avenue for investigation would be to conduct additional case studies and even large-n quantitative work to explore the dynamics of expansion to a greater number of groups and scenarios. Finally, the timing of expansion remains a key area for investigation, and probably one of the most difficult to pin down. Even if the opportunity and willingness factors matter, when they reach a critical boiling point is a key issue for policymakers and practitioners alike. Answering this question with specificity will likely require in-depth examination of primary sources that provide greater light on the internal decision-making processes of these groups.

Finally, this framework also has implications for the counterterrorism efforts that countries may seek to conduct. While reducing some of the contributing factors that lead to opportunity or willingness is not necessarily an incorrect approach, even the brief case studies above highlighted how multiple opportunity and willingness factors interacted and, in some cases, overlapped to create conditions that were fully ripe for expansion. Counterterrorism efforts should take note of this and be careful about designing a successful policy based on one factor alone. Although additional research is needed to assess how the opportunity and willingness approach fares when it comes to counterterrorism, there is reason to suggest that a more holistic policy will be more effective than a limited one.

Substantive Notes

[a] There is seldom a cut-and-dry line between inspired and directed attacks. Islamic State’s virtual planning model is a good example of this grey area, as some plots under this model approach a centrally directed attack while others appear to be slightly more than an inspired operation. Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Madeleine Blackman, “ISIL’s Virtual Planners: A Critical Terrorist Innovation,” War on the Rocks, January 4, 2017. [b] Note that, in this framework, expansion is very much a geographic phenomenon. A terrorist group choosing to attack a foreign embassy located within the group’s already existing area of operation is not considered here, although, as mentioned above, it could certainly be considered expansion and is a dynamic worth examining in the future. Some scholars have already carried out work along these lines in the form of large-n studies focused on the targeting of Americans by foreign groups. Eric Neumayer and Thomas Plümper, “Foreign terror on Americans,” Journal of Peace Research 48:1 (2011): pp. 3-17; Daniel J. Milton, “Dangerous work: Terrorism against U.S. diplomats,” Contemporary Security Policy 38:3 (2017): pp. 345-370; Daniel Meierrieks and Thomas Gries, “‘Pay for It Heavily’: Does U.S. Support for Israel Lead to Anti-American Terrorism?” Defence and Peace Economics 31:2 (2020): pp. 160-174; Victor Asal, Christopher Linebarger, Amira Jadoon, and J. Michael Greig, “Why Some Rebel Organizations Attack Americans” in Khusrav Gaibulloev and Todd Sandler eds., On Terrorist Groups: Formation, Interactions, Survivability and Attacks (London: Routledge, 2023), pp. 72-89; Eugen Dimant, Tim Krieger, and Daniel Meierrieks, “Paying Them to Hate US: The Effect of US Military Aid on Anti-American Terrorism, 1968–2018,” Economic Journal 134:663 (2024): pp. 2,772-2,802. [c] Although the author employs the “opportunity” and “willingness” framework here and prefers that terminology, other scholars have utilized a “push” and “pull” model imported from the study of organized criminal groups. Tin Kapetanovic, Mark Dechesne, and Joanne P. Van der Leun, “Transplantation theory in terrorism: an exploratory analysis of organised crime and terrorist group expansion,” Global Crime 25:1 (2024): pp. 1-25. [d] The opportunity and willingness framework could also be applied to individual decision-making processes regarding radicalization and carrying out attacks, but that level of analysis is not what is being examined here. This is focusing on the strategic decision of the group to expand and is an organizational-level analysis. [e] Given the close distance, it may be argued that the LTTE attacking in India does not even represent an expansion. However, such a change in the attack portfolio, even over a short distance, is likely a deliberate choice, given that not a single attack had occurred outside of Sri Lanka’s borders prior to 1990. [f] The term Khorasan means “rising sun” and refers to a historical region generally, though not exactly, in the same area as where ISK operates. Adrija Roychowdhury, “Why Islamic State in Afghanistan harks on the concept of Khorasan and what it means for India,” Indian Express, September 25, 2021. [g] Attribution for these individual events is challenging to say the least. Some of the attacks attributed to ISK appear to be attributed not because of a formal claim of responsibility, but at times on the word of “security sources.” Other times, the attribution is based on the activity of an Indian cell with the name of “Khorasan,” even though there is no indication that the actual ISK group had any involvement. “ISIS linked militant killed in Lucknow,” LeadPakistan, March 9, 2017.The GTD does include an earlier attack/plot attributed to ISK on October 1, 2016. However, that same attack/plot was also attributed to Maoists operating in the country. Ultimately, the author’s own research led to a conclusion that the nature of the incident was more consistent with other Maoist operations.

[h] This is not a new phenomenon. Regular human flows have aided the movement of operatives previously. The September 11 hijackers used a combination of business, tourist, and even one student visa to enter the United States. Thomas R. Eldridge, Susan Ginsburg, Walter T. Hempel II, Janice L. Kephart, and Kelly Moore, 9/11 and Terrorist Travel (Washington, D.C:. Staff Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, 2004).Citations

[1] “Eight Years After 9/11: Confronting the Terrorist Threat to the Homeland,” U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, September 30, 2009; “Violent Islamic Extremism: Al-Shabaab Recruitment in America,” U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, March 11, 2009.

Ubaydi, “Pledging Baya: A Benefit or Burden to the Islamic State?” CTC Sentinel 8:3 (2015): pp. 1-7.

[47] Catrina Doxsee, Jared Thompson, and Grace Hwang, “Examining Extremism: Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP),” Center for Strategic & International Studies, September 8, 2021; Amira Jadoon, Abdul Sayed, and Andrew Mines, “The Islamic State Threat in Taliban Afghanistan: Tracing the Resurgence of Islamic State Khorasan,” CTC Sentinel 15:1 (2022): pp. 33-45.

[48] See https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd

[49] Aaron Zelin, “ISKP Goes Global: External Operations from Afghanistan,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, September 11, 2023; Amira Jadoon, Abdul Sayed, Lucas Webber, and Riccardo Valle, “From Tajikistan to Moscow and Iran: Mapping the Local and Transnational Threat of Islamic State Khorasan,” CTC Sentinel 17:5 (2024): pp. 1-12.

[50] Nodirbek Soliev, “The April 2020 Islamic State Terror Plot Against U.S. and NATO Military Bases in Germany: The Tajik Connection,” CTC Sentinel 14:1 (2021): pp. 30-40.

[51] Andrew Roth and Pjotr Sauer, “Four suspects in Moscow concert hall terror attack appear in court,” Guardian, March 24, 2024; “Number of those injured in Moscow terrorist attack revised upward to 551,” TASS, March 30, 2024; “Russia says Islamic State behind deadly Moscow concert hall attack,” France 24, May 24, 2024.

[52] The geographic and human diversity of this appeal was highlighted in primary source documents leaked about the inflow of foreign fighters to the group. Brian Dodwell, Daniel Milton, and Don Rassler, The Caliphate’s Global Workforce: An Inside Look at the Islamic State’s Foreign Fighter Paper Trail (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2016).

[53] Adam Goldman, Eric Schmitt, and Hamed Aleaziz, “The Southern Border, Terrorism Fears and the Arrests of 8 Tajik Men,” New York Times, June 25, 2024.

[54] Neil MacFarquhar and Eric Schmitt, “An ISIS Terror Group Draws Half Its Recruits From Tiny Tajikistan,” Ne]w York Times, April 18, 2024.

[55] UNHCR, Global Trends: Force Displacement in 2023 (New York: United Nations, 2024).

[56] Ibid. UNHCR, UNHCR Mid-Year Trends 2014 (New York: United Nations, 2014).

[57] Marlene Laruelle, “A New Recruiting Ground for ISIS: Why Jihadism Is Thriving in Tajikistan,” Foreign Affairs, May 14, 2024.

[58] Soliev.

[59] Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Madeleine Blackman, “ISIL’s Virtual Planners: A Critical Terrorist Innovation,” War on the Rocks, January 4, 2017.

[60] Allan Woods, “The return of ISIS: How a Toronto case fits into the global resurgence of a terror group we thought had been defeated,” Toronto Star, September 15, 2024.

[61] Animesh Roul, “The Rise of Monero: ISKP’s Preferred Cryptocurrency for Terror Financing,” GNET Insights, October 4, 2024.

[62] Jessica Davis, “The Financial Future of the Islamic State,” CTC Sentinel 17:7 (2024): pp. 32-37; Roul. Stronger allegations of this connection have been made by Russian officials, but the veracity of these stronger claims is unclear.

[63] Jadoon, Sayed, Webber, and Valle.

[64] Tore Hamming and Colin P. Clarke, “Over-the-Horizon Is Far Below Standard,” Foreign Policy, January 2, 2022; Meghann Myers, “Post-withdrawal, no ‘over-the-horizon’ strikes in Afghanistan,” Military Times, May 12, 2023.

[65] David Vergun, “U.S. to Maintain Robust Over-the-Horizon Capability for Afghanistan if Needed,” DOD News, July 6, 2021.

[66] Asfandyar Mir, “Commentary: No Good Choices: The Counterterrorism Dilemmas in Afghanistan and Pakistan,” CTC Sentinel 16:10 (2023): pp. 40-55; R. Kim Cragin, “The Elusive Promise of ‘Over-the-Horizon’ Counterterrorism,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism (online), 2024.

[67] “Commander of U.S. Central Command General Michael Kurilla, Testimony before the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee,” March 7, 2024; Katherine Brucker, “On the Terrorist Attack at the Crocus City Hall in Moscow,” U.S. Mission to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, April 11, 2024.

[68] Natasha Bertrand, “US secretly warned Iran before ISIS terror attack,” CNN, January 25, 2024; Aamer Madhani, “US warned Iran that ISIS-K was preparing attack ahead of deadly Kerman blasts, a US official says,” Associated Press, January 25, 2024; Shane Harris, “U.S. told Russia that Crocus City Hall was possible target of attack,” Washington Post, April 2, 2024.

[69] Muhammad al-`Ubaydi, Nelly Lahoud, Daniel Milton, and Bryan Price, The Group That Calls Itself a State: Understanding the Evolution and Challenges of the Islamic State (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2014); Haroro J. Ingram, “An analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq magazine,” Australian Journal of Political Science 51:3 (2016): pp. 458-477.

[70] Amira Jadoon, Nakissa Jahanbani, and Charmaine Willis, “Challenging the ISK Brand in Afghanistan-Pakistan: Rivalries and Divided Loyalties,” CTC Sentinel 11:4 (2018): 23-29.

[71] Amira Jadoon, Allied & Lethal: Islamic State Khorasan’s Network and Organizational Capacity in Afghanistan and Pakistan (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2018).

[72] Ayesha Sikandar, “Assessing ISKP’s Expansion in Pakistan,” South Asian Voices, September 25, 2023.

[73] See https://theglobalcoalition.org/en/

[74] Kevin Doyle, “Moscow concert hall attack: Why is ISIL targeting Russia?” Al Jazeera, March 23, 2024.

[75] Brian Glyn Williams and Robert Souza, “The Consequences of Russia’s ‘Counterterrorism’ Campaign in Syria,” CTC Sentinel 9:11 (2016): pp. 23-30.

[76] Lucas Webber, “The Islamic State’s Anti-Russia Propaganda Campaign and Criticism of Taliban-Russian Relations,” Terrorism Monitor 20:1 (2022): pp. 7-10.

[77] Christina Goldbaum, “Suicide Attack Hits Russian Embassy in Afghanistan, Killing 2 Employees,” New York Times, September 5, 2022.

[78] Lucas Webber, Riccardo Valle, and Colin P. Clarke, “The Islamic State Has a New Target: Russia,” Foreign Policy, May 9, 2023.

[79] Golnaz Esfandiari, “IS Propaganda Increasingly Targeting Iran And Its Sunnis,” Radio Free Europe, June 6, 2017.

[80] These events were all referenced in Aaron Zelin’s Islamic State activity tracker between 2022 and 2023. Aaron Y Zelin, The Islamic State Activity Interactive Map, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, accessed October 10, 2024. See “Attack on Shia Shrine in Shiraz, Iran,” “Ten Arrested for Attack on Shah Cheragh Shrine in Shiraz, Iran,” “Two Islamic State Cells Arrested in Iran,” and “Leader of Khurasan ‘Province’ Operational and Media Network Arrested in Fars, Iran.”

[81] Leila Fadel and Peter Kenyon, “An Afghan branch of ISIS claims responsibility for a deadly attack in Iran,” NPR, January 5, 2024.

[82] Abdul Sayed and Tore Refslund Hamming, “The Growing Threat of the Islamic State in Afghanistan and South Asia,” Special Report: United States Institute of Peace 520 (2023): pp. 1-28; Haroro J. Ingram and Andrew Mines, “From Expeditionary to Inspired: Situating External Operations within the Islamic State’s Insurgency Method,” ICCT Analysis, November 23, 2023.

[83] Jadoon, Sayed, Webber, and Valle.

[84] Sayed and Hamming.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News