As exiled activists, we were stunned to see the former human rights lawyer cosying up to Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Keir Starmer’s recent visit to Saudi Arabia laid bare the moral bankruptcy of Britain’s foreign policy – a policy that eagerly courts despots while slamming its doors on those fleeing their repression.

Starmer’s trip, sold as a bid to bolster trade and security partnerships, conspicuously sidestepped any mention of Mohammed bin Salman’s grotesque human rights abuses.

Instead, it signalled the UK’s quiet complicity, prioritising arms sales and economic ties over accountability.

Against the backdrop of rising anti-immigration rhetoric, especially from Nigel Farage’s Reform party, Labour’s apparent willingness to echo these sentiments only deepens the sense of abandonment faced by Saudi exiles.

With Western governments increasingly appeasing authoritarian regimes, even the right to political refuge is no longer guaranteed – and Britain, it seems, is more than willing to play its part in this descent.

For years it gave unwavering support to Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen and turned a “blind eye” to the persecution of exiles within Britain.

In September, revelations emerged about political donations to Labour MPs like David Lammy from Saudi-linked figures, illustrating how deeply intertwined British politics is with Saudi interests.

Starmer’s silence mirrors a larger pattern – one that exiles know all too well. Last May, we were among Saudi dissidents at The Quest for Democracy in Saudi Arabia conference in Washington D.C., a gathering brimming with both hope and despair.

Forced from their homeland, these activists demanded more than the illusion of reform sold under Vision 2030 – they envisioned a Saudi Arabia truly chosen by its people.

It was an extraordinary meeting of minds – activists, feminists, and thinkers united not by geography but by the shared trauma of repression and exile.

The central question hanging over the event was both tantalising and elusive: Could Saudi Arabia ever embrace a government truly chosen by its people?

The excitement was palpable, yet bitterness lingered too. Nearly everyone present had fled Saudi Arabia in 2017, the year of Mohammed bin Salman’s rise to power.

Stories of repression, loved ones imprisoned or silenced, and the lingering question – when was the last time any of us felt safe enough to return? – cast a shadow over every conversation.

Deliberate distraction

Since MBS became crown prince and de facto ruler, his reign has been defined by aggressive suppression of political dissent, targeting human rights advocates, government critics, and anyone who dares to challenge the status quo.

Yet Western media often focus on the dazzling promises of Vision 2030 – polished by high-profile consultants like McKinsey.

This glossy veneer has seen MBS win international praise for what appears to be gradual social liberalisation.

Cinemas have reopened, international concerts and festivals now welcome women, and the kingdom’s first opera house has made headlines.

To many in the West, these developments suggest the dawn of a new era – one of openness, prosperity, and vast opportunities for investment and tourism.

Beneath this lies a far more troubling reality.

These cultural shifts do not signal genuine reform but rather deliberate distraction aimed at the kingdom’s youth population – 63% of whom are under 30 – from ongoing and deepening human rights violations.

As Madawi Al-Rasheed has pointed out, the crown prince’s focus on entertainment and spectacle serves to project a false image of progress and freedom, all the while maintaining tight control over political discourse.

This carefully constructed mirage is designed not just to placate a restless younger generation, but also to rehabilitate the regime’s international reputation.

The crucial question remains: How long can this veneer of openness hold, without real, substantial reforms beneath the surface?

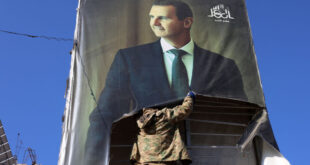

Image versus reality

Behind Saudi Arabia’s meticulously crafted global image, the regime’s tightening grip on dissent has led to a quiet but noticeable exodus of Saudis seeking refuge abroad.

The regime’s intolerance for opposition has only deepened, with the horrific murder of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 serving as a grim reminder of just how far the crown prince is willing to go to silence critics, even those beyond Saudi borders.

Any form of opposition – whether it’s questioning the ambitious scale of Vision 2030 or advocating for basic freedoms and equal rights – is met with swift and brutal repression.

Women’s rights advocates who challenged the male guardianship system or fought for equal rights have been detained, imprisoned, or silenced.

Many Saudis from different walks of life have found themselves locked up simply for crossing the regime’s invisible ‘red lines’ – whether by criticizing the monarchy, questioning the crown prince’s favoured projects like Vision 2030, or expressing dissent on newly introduced social policies.

Even well-respected figures, like economist Isam al-Zamil, have not been spared. His quiet criticism of the regime’s privatisation plans resulted in his detention – a stark reminder of the state’s refusal to tolerate any challenge to its tightly controlled narrative.

Most worryingly, executions have surged under Mohammed bin Salman. Between 2010 and 2021, over 1,200 people were executed, with 147 more – including 31 women – meeting the same fate in 2022 alone.

Last year the number of executions doubled to 345 people, equating to almost one a day.

Time to go

As long as Saudi Arabia remains a place where political dissent is ruthlessly crushed, its people will continue to flee in ever-growing numbers.

Feminists, students, secularists, and Islamists alike have fled the kingdom in search of safety across Europe, the US, Canada and Australia.

According to UNHCR data, the number of Saudis seeking asylum abroad has risen sharply over the past decade.

In 2013, there were 575 Saudi refugees and 192 asylum seekers; by 2023, those numbers had swelled to 2,100 refugees and 1,748 asylum seekers.

The number of Saudi exiles could soon reach 50,000, a reflection of a country not at war, but suffocated by authoritarianism and a profound erosion of individual freedoms.

A recent report by human rights group ALQST sheds light on the many reasons why Saudis have fled the kingdom – during a period supposedly marked by liberalisation.

Among the most commonly cited are a lack of political and religious freedom, threats to personal safety due to activism, and vulnerabilities tied to sexual orientation.

Alarmingly, 25% of respondents pointed to domestic violence, a stark reminder of the regime’s failure to protect its citizens.

Even in exile, many reported facing cyber-surveillance and online harassment from Saudi authorities.

For these individuals, the fear of returning home is palpable, with the majority stating they would not feel safe, even with official assurances.

Their fears are well-founded. In 2022, Salma al-Shehab – a Saudi student pursuing her studies in Britain – was arrested upon returning home to visit her family.

Her sentence? Thirty four years in prison simply for posting tweets in support of human rights.

Real reform

As Saudi exiles continue to escape repression at home, they have found new ways to resist beyond the reach of the regime’s iron grip.

While social media remains an important tool for some, their activism extends far beyond digital campaigns.

These exiles are forging alliances with international human rights organisations, engaging with global legal frameworks, and using public diplomacy to expose Saudi Arabia’s violations on the world stage.

Their efforts aim to reshape global perceptions and push foreign governments to reconsider their alliances with the Saudi regime by advocating for policy changes that hold the regime accountable in diplomatic and legal arenas.

They are not just speaking out against Riyadh but exposing the complicity of Western allies who prop up its brutality, Starmer included – despite his past career as a human rights lawyer.

Simultaneously, many exiles are organising collective efforts through institutions that advocate for deep, lasting reform.

Organisations like ALQST have become key players in documenting human rights abuses, leveraging global platforms to inform international debates.

These institutions are more than opposition – they offer blueprints for legal and civic reforms that could guide Saudi Arabia’s future.

Other groups, like the National Assembly Party (NAAS), unite a diverse coalition of voices, representing liberals, progressives, and feminists, to envision a democratic and inclusive future.

Their work counters the regime’s narrative and showcases the governance and civic life Saudi citizens deserve.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News