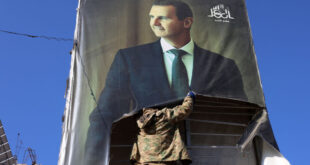

With only a few days left of Joe Biden’s administration in the White House, and as Donald Trump once again prepares to take over the American presidency, the Middle East will greet the new government as a region both in turmoil and rapid transition. While a political and military ceasefire between Israel and Hamas continues to be chased, the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s three-decade-long rule in Syria, and the rise of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham’s (HTS) Ahmed al-Sharaa (also known by his nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Jolani) has thrown a spanner into the region’s proverbial cogwheel of diplomacy and realpolitik.

Al-Sharaa is what some are calling a lapsed jihadist. He has blamed the naivete of youth for his dalliances with Islamist groups. Having previously been involved with both the so-called Islamic State (also known as ISIS or Daesh in Arabic) and al-Qaeda alike, the former rebel chief has exchanged his Islamist credentials and camo fatigues for mainstream politics and diplomacy as he works to concretise his control over Damascus.

A stream of diplomats from across the region and the West, including the United States (US), have met al-Sharaa, who appears in public in Western-style clothing, with a cabinet-like transitional government structure by his side. This includes his former commanders in core positions. General Murhaf Abu Qasra (nom de guerre under the HTS Abu Hassan al-Hamawi), who designed military grand strategies for the HTS, is now the defence minister. Assad Hassan al-Shaibani, a founder of the HTS-led Salvation Government which controlled territories such as Idlib, is the foreign minister.

The above represents the core team for al-Sharaa’s outreach to the world, which no doubt has been steadfast. This is not the first time that the international community has had to deal with a jihadist ideologue, whose movement is in control of a state. The Taliban-led interim government systems in Afghanistan continue to hold power in the country, four years after the collapse of the Republic at the time led by Ashraf Ghani. However, al-Sharaa’s Syria has been mainstreamed much faster. As per scholar Aaron Zelin’s database, the HTS-led government has had formalised engagements with nearly 30 countries. Comparatively, in the same time frame, the Taliban had managed engagements with only seven states.

The reasons for the pace of this ‘new’ Syria’s return are rooted in geopolitics, ranging from regional dynamics between Iran and the Gulf states to Russia’s engagements in the country suffering a critical setback, resulting in Moscow’s diminishing presence in the region. Even during the last leg of Assad’s reign, the Syrian leader had started to increase his political bets within the Arab fold, after being shunned during Arab Spring protests in the country.

There was a sense of hedging away from the idea of being a client state to Iran and finding solace and acceptance within the Arab brethren for long-term stability. Over the last few months, the erstwhile president did not react militarily to Israeli transgressions within his country’s territories that targeted Iranian militias and infrastructure allegedly belonging to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). As per some reports, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) even discouraged Assad from reacting after Israel bombed an Iranian diplomatic mission in the Syrian capital, which led to an extended military exchange between Israel and Iran.

The regional discourse around arresting the slide of Syria’s political future is much more intricate than just a Shia-Sunni rivalry or an Israel-Iran contestation. Additionally, it is also much more consequential than a US-Russia or US-China competition. The outcome of Syria’s political direction is hinged as much on regional geopolitics as it is on al-Sharaa’s political acumen in navigating the country’s internal fissures and external geopolitics.

Some actors are going to be more critical to manage than others. To begin with, while Iran is putting a brave face on the outcomes in Syria, the fact remains that it has, for now, lost considerable strategic depth in the region as a result. A new presidency in Lebanon aided by the US and Saudi Arabia aimed at undercutting any resurgence by Hezbollah has further added to its woes. Tehran will look to regain some, if not all, of its influence in a protracted manner over the months to come. Similarly, Türkiye, which both holds on to parts of northern Syrian territory, supports the Syrian National Army (SNA) rebel group and looks upon the US-supported Kurdish groups as a national security threat, will also face an understated but prominent ideological contestation with Saudi Arabia. Both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have spent a better part of the past decade bringing down the influence of groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, their affiliates, and political Islam in itself as a concept. They have also benefited from the dissolution of Hamas, Hezbollah, and Islamic State, amongst others, via the gamut of conflicts shaping the landscape.

Pivoting from geopolitical challenges, al-Sharaa’s ideological challenges are yet to be played out in the open. The ease with which al-Sharaa seems to have used Islamist ideologies in the past, and with him now moving towards managing a state and talking about elections, constitutions, and democratic norms, puts him in a direct clash with his peers and, perhaps, many within the HTS as well. The scholar Cole Bunzel has highlighted in his works many Salafist ideologues across the region and beyond who have already targeted al-Sharaa’s stance on constitutional democracy instead of building an Islamic state. In 2019, HTS’s chief of religious authority wrote that “Democracy, from a creedal standpoint, is opposed to Islam, as Islam is premised on giving rule to God, while democracy is premised on giving rule to what is apart from God, whatever that may be.” The HTS further added in the same year that the “Sovereignty of the sharia is the aim of jihad”. Currently, al-Sharaa seems to stand against his own institution’s diktats.

Some cracks within al-Sharaa’s ‘new’ Syria are also already visible. A new group from Syria, under the tutelage of Egyptian jihadist Ahmed al-Mansour for new propaganda output, has already started to challenge the political leadership of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Cairo. Mansour has called for Egyptians to mobilise on 25 January, the anniversary of the Arab Spring and the toppling of erstwhile President Hosni Mubarak’s three-decade-long rule. Pro-Sisi media in Egypt has begun to counter Mansour’s narrative. While this is the first instance of a Syrian jihadist aiming for a foreign state’s political rule, it may not be a one-off event. Other similar groups may take shape in the country, as those who have fought with or alongside al-Sharaa may well have different political aims and might just completely disagree with his choice.

Finally, the fact remains that much of the positive euphoria around al-Sharaa is yet to be contextualised. There remain more points of infraction than celebration. For regional states, it is a battle for influence and ideological one-upmanship. For Europe, it is about mitigating and managing any potential influx of refugees as the continent continues to reel from the political fallout, such as the rise of the far-right, as a consequence of previous such mass movements beginning in 2013. The US intends to continue its counter-terror operations against Daesh, aiding Israeli interests, and maintaining a level of power projection across the region. Meanwhile, Russia, Iran, and China will intend to renew and reaffirm their influence in the coming future, as a part of big-power contests where the Middle East is one of the three critical theatres, joining Ukraine and the Indo-Pacific.

Amidst all this, al-Sharaa must survive, thrive, and gain the world’s confidence. He is already off to a better start than what the Taliban had managed. However, his longevity will depend as much on his political pedigree, as it would on the management of his ideological realities.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News