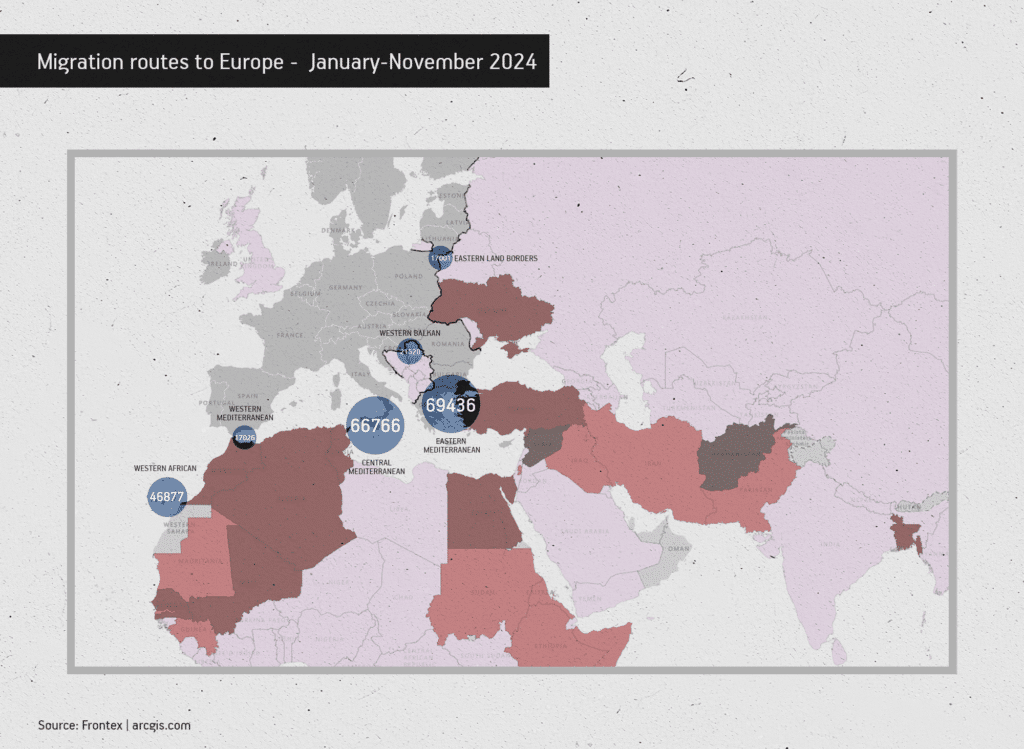

Just over 220,000 migrants were detected trying to cross into Europe illegally in the first 11 months of 2024, according to Frontex data. That represents a decrease of about 40 per cent from 2023, and is several orders of size smaller than the numbers seen in 2015, when around 1 million Syrians made their way to Europe to escape the civil war back home. However, the perilous Western African route saw a record 46,843 people reach the Canary Islands illegally in 2024, up 19 per cent from 2023.

The breakdown per migratory route in January-November 2023 was as follows:

Eastern Land Borders route: 16,530 arrivals

Western Balkan: 20,526

Eastern Mediterranean: 63,935

Central Mediterranean: 62,034

Western Mediterranean: 15,412

Western African: 41,756

- Overview

Even though the total number of migrants detected trying to cross into Europe illegally fell further in 2024, the number of asylum applications remains high and on course to top 1 million again. Since 2020, EU+ countries (EU states plus Norway and Switzerland) have been receiving increased numbers of asylum applications. In 2023, 1.1 million applications were lodged in the EU+, marking an 18 per cent increase from the previous year, and the most for seven years. During the first half of 2024, 513,000 applications were lodged in the EU+, which is more or less comparable to the first half of 2023, when the highest January-June level was recorded since the refugee crisis of 2015. The EU Agency for Asylum (EUAA) notes that more applications are usually lodged in the second half of the year. German news agency DPA and newspaper Welt am Sonntag reported in January that the EUAA’s full-year 2024 figure for asylum applications in the EU+ came in at just over 1 million, down 12 per cent from 1.14 million in 2023.

Given the surge in support for right-wing populist parties across the continent in the June 2024 elections for the European Parliament, European politicians have been scrambling to look tough on migration.

In September, Germany, one of the main recipients of migrants to the EU, announced the introduction of spot controls on all of its borders, following a fatal knife attack by a Syrian asylum seeker who was about to be deported in the Western town of Solingen. At the time, German Interior Minister Nancy Fraser told a press conference the checks would not only limit migration but also “protect against the acute dangers posed by Islamist terrorism and serious crime”.

Such border controls had already been in place with four of Germany’s neighbours – Austria, Poland, Czechia and Switzerland – and were prolonged that month. Additionally, entirely new controls were introduced on Germany’s borders with France, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark.

Importantly, the checks were introduced against the backdrop of regional elections, in which the far-right AfD made exceptional gains, winning in the eastern state Thuringia and coming second in Saxony. Migration, of course, was a central topic during the election campaign.

Italy, headed by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni whose Brothers of Italy party has far-right roots, has been another major recipient of migrants and experimented in 2024 with opening hotspots to process asylum applications outside its territory in Albania. Legal challenges have undermined the project. Similar scenarios have been explored by the UK and Germany.

In Central and Eastern Europe too, politicians have either maintained their tough stances on migration (if on the right of the political spectrum) or hardened them (if liberals).

The Hungarian government of Viktor Orban has taken a strict line on immigration since 2015. This year, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) imposed a 200-million-euro fine on Hungary (plus 1 million euros for each day of delays in not implementing the ruling), for its restrictive migration policies, which were determined to make it virtually impossible to apply for asylum while also allowing for pushbacks at the border.

Despite the tough stance on Hungary from the European Commission and the European Court of Justice, the European mainstream has actually been shifting significantly in Orban’s direction over the last few years. So much so that the Hungarian leader felt vindicated enough to proclaim that his old predictions about the non-viability of the EU’s passport-free zone and migration policies were coming true.

“Since 2015, I have been called either an idiot or an evil person for my stance on migration. But, at the end of the day, everyone will agree with me,” Orban told reporters at his international press conference in October in Strasbourg.

Slovakia had already toughened its position on immigration at the end of 2023 when Robert Fico returned to power, governing together with two other parties, one of them the extreme-right Slovak National Party. Soon after Fico came to power, the country stopped being a regional hub of sorts for migrants trying to make their way from the Balkan route or even Belarus into Western Europe.

And in Czechia, the populist ANO party of former premier Andrej Babis looks poised to retake power in the 2025 general election, possibly in league with the far-right SPD, with Babis exploiting the migration issue already for months.

To me and many other professionals working on migration and refugee issues, it’s just a political document and a very populist one at that, full of fear and playing on the fears of people.”

– Marianna Wartecka, Board Member of the Ocalenie Foundation

Perhaps most surprising of all has been that Poland’s new liberal government, led by Donald Tusk, chose to not only continue the anti-migration policies of the previous nationalist-populist Law and Justice (PiS) government, but to actually take them one step further. In fact, Poland under Tusk could become the most hardline country on migration in the whole of Europe in 2025.

In mid-October, Tusk, seen as a centrist politician, announced the suspension of asylum rights due to pressure on its border with Belarus, which is being caused by the regime of President Aleksandr Lukashenko bussing tens of thousands of migrants to its borders with the EU and herding them across to foment a crisis. In mid-December, the government published proposed legislative changes that would allow the executive to suspend asylum rights by decree for a period of 60 days on a specific segment of the border.

If the Polish parliament approves the legislative changes, which is likely, Poland will become the first country in the EU to actually write in law the suspension of the right to asylum, so far considered a fundamental human right. Importantly, pretty much at the same time when the Polish government presented the proposed legislative changes to the public, the European Commission appeared to give its green light for such legal changes. In mid-October, the EU Commission issued a communication in which it indicated that member states can, in such special circumstances as a hybrid war with Russia and Belarus, introduce measures that “may entail serious interferences with fundamental rights such as the right to asylum.”

A further indication of how widespread the anti-migration mood was in 2024 is the call made in October by 17 EU countries demanding a “paradigm shift” in the bloc’s migration policy, a strengthening of the external borders, and a radical toughening of the return procedures for asylum seekers who have had their applications turned down. This is despite EU countries adopting, after years of negotiations, a major overhaul of migration rules dubbed the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum. Migrant and human rights NGOs have condemned the pact already introducing a more restrictive approach to helping migrants and refugees.

The Migration Pact speeds up asylum procedures for some categories of migrants, quickening the deportation of those rejected. It envisages emergency procedures for crisis periods which allow for the prolonged detention of migrants. It also introduces a controversial burden-sharing mechanism, under which migrants can be relocated from countries of arrival to less exposed ones, or the latter can help support the costs of processing applicants.

For some EU governments the new Migration Pact does not go far enough. The pact was rejected by Hungary and Poland – although this does not prevent it from entering into force – while others in Central Europe abstained on it. Babis described the Migration Pact as a “huge betrayal” that would lead to the “insidious disease” of mass illegal migration, “a cancer that is destroying European society”. The October call by the 17 EU countries indicates many others want to go even further in closing the EU’s borders to migrants than the Migration Pact already does.

“We’re already hearing that, during the Danish Presidency, which comes after the Polish one in the first half of 2025, they plan to present even bigger changes to the migration and asylum law in the European Union than the Migration Pact has,” Marianna Wartecka, a board member at Fundacja Ocalenie, one of the main NGOs dealing with migration in Poland, told BIRN in an interview.

“The plan is to give [EU border agency] Frontex more power, including the power to operate officially in third countries as well as to assist in deportations from third countries to other third countries,” Wartecka continued. “Mass deportations will be made easier than they are now, and the externalisation of migration approach will be expanded.”

In the meantime, CEE countries are having to deal with the reality of immigration and how it will transform their societies.

In Poland, migrants from non-European countries entering via the Belarusian border are a small minority of the total migrant population in the country. There were about 30,000 attempted entries and around 2,000 asylum applications accepted on the Belarusian border in 2024, versus 1 million Ukrainian refugees residing in the country.

In October, when Tusk announced the suspension of the right to asylum on the Polish-Belarus border, he also spoke about his government’s efforts to adopt, for the first time, a migration policy for the country – indicating the government is ready to take ownership of the fact that Poland has turned into a destination country for migrants.

Since then, the government has published a 35-page document that sets out the basic principles of a migration strategy. Major organisations working on migration in Poland got to express their views on the document post-factum, during a public hearing on November 25. Most of them lambasted the document for depicting migration primarily as a threat and being scant on details otherwise.

“The language of the document depicts migration as a negative process overall, as a social problem which requires control,” Mikolaj Pawlak, a sociologist specialising in migration from the University of Warsaw, told BIRN. “But I try to take heart in the fact that the document is open and so, starting from the premises outlined in it, everything is possible.”

Pawlak pointed to the person in charge of the policy being Michal Duszczyk, deputy interior minister, who is one of the country’s foremost experts on the issue of migration and, Pawlak believes, “very conscious that migration is not something you can fully control”, despite public claims to the contrary by Tusk and his colleagues.

“My hope is that behind the tough talk that Tusk engages in for electoral reasons, the experts in charge and the various ministries will be implementing measures that are really needed to help with the integration of migrants,” Pawlak said, adding that there were positive signs out there already if one took a closer look at measures adopted by the various government branches.

“You anyway cannot address the problems migrants face in Poland today just via a migration policy,” Pawlak said. “Complex actions across sectors are needed.”

Wartecka from Ocalenie has a different opinion: “Integration is a two-way street,” she argued. “If you make Polish society afraid of migrants, integration won’t work even if you provide institutional instruments for integration like integration centres for foreigners for example.”

“This kind of rhetoric that is the main tone of the strategy, that we should be afraid, actually compromises many efforts towards integration,” Wartecka said.

- Signals to watch in 2025

Implementation of the EU Migration Pact: The new Pact on Migration and Asylum entered into force in June 2024 and should start being implemented after two years, in June 2026. However, as of mid-December 2024, half of the EU countries had failed to submit their National Implementation Plans before the deadline set by the EU Commission, which points to likely delays – if not more serious derailments – in the implementation of the plan. The Polish government has said it has no intention of submitting its National Implementation Plan soon after the deadline and the pact as it stands today is incomplete.

Poland’s legislation on asylum and migration policy: Poland’s parliament will vote in 2025 on the government’s proposal to introduce “temporary and territorial” suspension of the right to asylum into national legislation. If that passes, that will be the furthest a European country has gone so far in moving away from safeguarding refugee rights, by including the possibility of suspending the right to asylum directly in national legislation. Other countries may be emboldened to act in a similar manner.

Changes to Geneva Convention in the works? The Times reported on February 3 that it has seen a diplomatic paper, drafted by Poland and discussed by EU interior ministers at the end of January, which looks to overhaul the 1951 Refugee Convention that prevents countries from rejecting asylum seekers at their borders, enshrined in the fundamental principle of non-refoulement, in what the paper said may be one of the biggest shifts in migration policy in decades. “It should be noted that these principles were developed after the end of the Second World War, and were characterised by a very different geopolitical situation to that of today,” reads the diplomatic paper, The Times reported.

Czech election: Parliamentary elections to take place in Czechia in October 2025 are likely to bring the populist billionaire Andrej Babis back to power, possibly in coalition with some far-right political force. Babis, who is already speaking aggressively against immigration, is likely to toughen the country’s already none-too-soft line on this matter. That will make the entire region determined to maintain a hardline on immigration.

War in Ukraine: While the inauguration of Donald Trump might bring speedy peace negotiations in Ukraine, perhaps to the detriment of Kyiv, it is entirely possible that the war will also continue for another year or more. With Russia systematically attacking civilian infrastructure, especially the energy infrastructure, the civilian population – increasingly weary – might be pushed towards a new wave of emigration if more significant and violent developments ensue. As before, countries in CEE would be the first ports of call for the new refugees.

The language of the document depicts migration as a negative process overall, as a social problem which requires control.”

– Mikolaj Pawlak of the University of Warsaw

Situation in the Middle East: Following the downfall of the Assad regime, Europe is busy counting its Syrian refugees to see how many it can send back and how fast. But ever since Israel’s war in Gaza in retaliation for the Hamas terrorist attack in October 2023, followed by its attack on Hezbollah and southern Lebanon and heightened tensions with Iran, the situation in the Middle East remains fraught. While European countries are doing their best to seal themselves off from new arrivals, the rich continent remains the top destination for those seeking to escape countries in the region if conflict expands.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News