Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the US has provided 43 per cent of countries’ direct military commitments to Kyiv, according to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. After the US, the only other double-digit contributor is Germany at 12 per cent. The third largest contributor is the UK at 9 per cent.

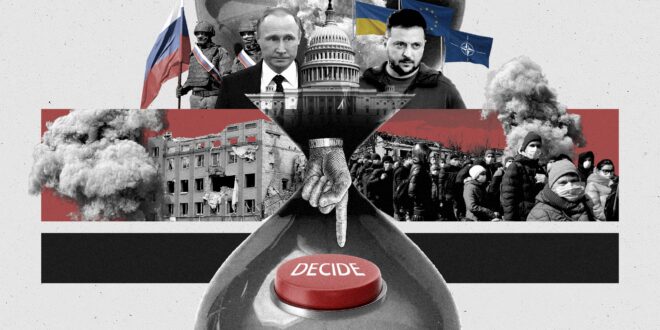

This puts into stark relief what is at stake for Ukraine as the administration of Donald Trump comes in. Without continued US military and financial support, an already-stretched Europe and others will have to take up the slack.

For 2025, the G7 agreed on a scheme in October 2024 to use profits from frozen Russian state assets to fund about 50 billion dollars of aid to Ukraine, in part because such financing using domestic resources was proving increasingly hard to secure. If all goes to plan, the G7 would begin disbursing the funds by the end of the 2024, which a Western official told CNN means that, “essentially, Ukraine is financially secure all 2025.”

- Overview

As Russia’s three-day “special military operation” in Ukraine enters its fourth year, the situation on the battlefield is seeing Russian armed forces continue to make territorial gains but at a shocking rate of casualties.

Data from the Washington-based Institute for the Study of War (ISW) showed that in November 2024, Russian forces took an area equivalent to the size of New York City – the worst monthly figure for Ukrainian defenders since September 2022 – bringing the total so far in 2024 to about 2,656 square kilometres. In all of 2023, Ukraine lost 2,233 square kilometres of territory. Russian control of Ukrainian territory has increased to 17.9 per cent as of 30 November 2024 from 17.4 per cent a year earlier.

The gains are coming at a rising cost. According to figures released by the UK’s Defence Ministry, the rate of casualties among Russian troops reached an all-time high in November 2024 at an estimated 45,690, with an average of 1,523 deaths each day and more then 2,000 reached in a single day for the first time on November 28. The ministry said it was the fifth consecutive month the overall figure had increased.

Using official reports, online obituaries on social media and images of tombstones, independent outlets estimate Russian deaths at 113,000 to 160,000, and casualties at 462,000 to 728,000. In a rare admission, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said in December 2024 that 43,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed since Russia’s full-scale invasion began.

Experts say the war has thus moved from 2023’s stalemate to one where Russia is sapping the strength and probing the defences of the outnumbered Ukrainians in order to gain as much territory before Trump was inaugurated on January 20, 2025 and force Ukraine to enter any ceasefire negotiations on the backfoot.

Most now assess that the war in its current form will probably end in 2025. Zelensky is already on the record as saying that the war will “end sooner” than it otherwise would have once Trump becomes US president. Good Judgment, a firm of “superforecasters”, puts the likelihood that Russia and Ukraine will announce a ceasefire with an intended duration of at least 28 days before October 1, 2025 at 34 per cent.

Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, in October 2024 laid out four scenarios for the end of the war in Ukraine:

‘Long war’ – An attritional conflict giving each side the possibility to exhaust the other. Ukraine would continue to fight and try to rebuild at the same time, while incurring ever greater human losses on the battlefield and to migration.

‘Frozen conflict’ – An armistice that would stabilise the front line where it is.

‘Victory for Ukraine’ – A Western policy shift on support that allows Ukraine to force Russia back to at least the demarcation line of February 2022.

‘Defeat for Ukraine’ – Ukraine’s acceptance of Russian terms of surrender (change of government, demilitarisation, neutrality, abolition of Ukrainian sovereignty) and territorial losses.

Dmytro Kuleba, Ukraine’s former foreign minister, adds a fifth scenario: the war in Ukraine could actually intensify under Trump due to the powder-keg of Putin, Zelensky and Trump being in a “cannot-lose standoff.”

Certainly, which of those four or five scenarios plays out will largely depend on the five major influencers on the war – Russia, Ukraine, the new US administration, the EU and China.

Russia may not be in the strongest position, but it could certainly end the war tomorrow if it so chooses. That is unlikely for as long as Putin remains holding the levers of power in Russia. “First off, there’s no problem getting Kyiv to a negotiating table, it’s getting Moscow. The problem with Putin is that his demands are to take over Ukraine, so nothing short of that is going to satisfy him. You can’t start talking about ceasefires, demilitarised zones, autonomous regions, and all that stuff and satisfy Putin because he’ll never be satisfied. Somebody like that just has to be stopped,” Kurt Volker, former US ambassador to NATO and Trump’s former special representative for Ukraine negotiations, told Meduza.

I think almost everybody else among the elites in Russia knows that this war was a huge mistake and really costly to Russia.”

– Kurt Volker, former US ambassador to NATO

Beyond Putin, there is Russia itself, where polls consistently show support for the war in Ukraine at somewhere around 70 per cent. As the Russian historian Sergei Medvedev observes in his book A War Made in Russia, Russia finally found its ultimate national idea after a search lasting three decades since the collapse of the USSR: war. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was not merely an obsession of Putin, Medvedev argues, but rather the result of two decades of “authoritarian degradation and post-imperial ressentiment”, which Russia, by and large, embraced with enthusiasm, seeking to relive its own military glory and colonial past.

However, as Volker notes in his interview, “I think almost everybody else among the elites in Russia knows that this war was a huge mistake and really costly to Russia.” That means Trump, who Zelensky has been busy expressing his “deep gratitude” to for showing “strong resolve” towards ending the war, has leeway to push Putin to the negotiating table and force a deal on both sides that involves Ukraine giving up land for peace.

In that case, Ukraine would certainly push for security guarantees, such as joining NATO or some other arrangement involving European forces on Ukrainian soil. At the Foreign Affairs Council meeting in Brussels on December 16, 2024, the matter of boots on the ground in Ukraine was discussed. “Some force on the ground is likely at some point. Unlikely it’ll be Americans. That leaves us with Europeans,” one diplomat told Politico, adding that talks were “on the conceptual level” at this stage.

- Signals to watch in 2025

Trump’s picks: The new US president has assembled a team that contains both Russia hawks and others viewed as too sympathetic to Russia. At one extreme is Tulsi Gabbard, the nominee to lead the intelligence services, who has endorsed Russian justification for invading Ukraine over labs creating bioweapons and indulged in other conspiracy theories, and Vice President JD Vance, who has refused to call Moscow an enemy and said negotiating with Putin is necessary to end the war. Yet they may not play the major role in Trump’s ‘Ukraine team’. That might fall to Secretary of State Marco Rubio, a noted Russia hawk; Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth, who has flip-flopped on the issue; and Lieutenant General Keith Kellogg, Trump’s pick to oversee negotiations between Russia and Ukraine, who has helped draft a plan that would make aid to Ukraine contingent on its participation in peace negotiations, while Putin would be warned the US would boost support for Ukraine if the Kremlin refuses talks.

War fatigue: Czechia and Poland have been among Ukraine’s staunchest supporters since the earliest days of the war. Yet after almost three years of a conflict that shows little sign of ending, the mood has soured. One of the latest surveys found that about 65 per cent of Czechs were in favour of an early end to the war even at the expense of territorial losses to Russia. The STEM poll also found that a majority of the population opposes negotiations on Ukraine’s accession to the EU (64 per cent) and is against continued military support to Kyiv (54 per cent). In Poland, results of annual research into attitudes towards Ukrainian migrants coordinated by Robert Staniszewski from Warsaw University were published in June. According to the findings, 95 per cent of Poles believe that financial benefits for Ukrainian refugees should be reduced; 60 per cent also said they would like to see the refugees returning to their own country once the war is over. Additionally, only 31 per cent of those interviewed were sure Poland should continue to support Ukraine, as compared to 62 per cent in January 2023. And 72 per cent of interviewees said that, regardless of the fact that the war is still ongoing, Poland should primarily watch out for its own interests.

Russia gains new V4 friends: The pro-Russia camp within the Visegrad Group of countries used to be confined to an isolated Hungary, whose leader Viktor Orban seems not to care about the stance of his European allies or indeed Russia’s spying on his own government. This changed when, at the end of 2023, Robert Fico’s three-party coalition took over from a succession of pro-Ukrainian/pro-EU governments in Slovakia. Fico has given interviews to Russian media and intends to attend World War II commemorations in Moscow in May at the invitation of Putin. All eyes are on the Czech parliamentary election expected by October 2025, which polls suggest should see the pro-Ukrainian but highly unpopular coalition of Prime Minister Petr Fiala ousted at the expense of the ANO movement of the billionaire former premier Andrej Babis. Babis has taken an equivocal stance over the war in Ukraine.

The economics of war: If the US were to stop all funding to Ukraine, then the onus would fall on Europe to make up the shortfall. But the continent is facing a crisis of low growth, which will only be exacerbated by a Trump administration that promises to impose tariffs of up to 20 per cent on European imports to the US and insists on NATO members spending more on defence. Yet money is already tight, with most EU states facing big deficits and piles of debt. The European Commission said in September that the total amount of aid provided by the EU and its member states to Ukraine had reached 118 billion euros since the start of Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine. To pay for future aid, the EU intends to use more profits from frozen Russian assets as well as perhaps later on seized Russia assets themselves, such as Russian central bank reserves held in European bank accounts. The EU Commission has proposed a macro-financial assistance loan of up to 35 billion euros for Ukraine, the EU’s contribution to an overall financial assistance package of up to 50 billion euros between the EU and the G7. Yet EU populations are growing weary of stagnant growth and spending cuts while paying Ukraine to wage war, as populist parties topping recent elections and polls show.

Russia faces its own difficult economic choices: The Russian rouble fell to 110 against the US dollar on November 27, its lowest level since the start of the war in Ukraine. Falling energy prices and tighter sanctions have caused a drop in Russia’s export revenues, while the weaker rouble will increase the price of imports Russia needs to wage its war. Analysts expect the central bank’s current interest rate of 21 per cent to rise in order to stabilise the rouble and curb inflation. However, raising rates will slow the economy in 2025. “Defence spending is eating up the budget. And if Moscow’s energy revenues – the lifeblood of the Russian economy – and its imports of Western-made dual-use goods slow significantly, it may face an economic and military crisis,” Theodore Bunzel, managing director and head of Lazard Geopolitical Advisory, and Elina Ribakova, non-resident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, wrote in Foreign Affairs.

Sanctions keep up pressure: The focus of the EU’s 15th sanctions package against Russia, adopted in December, is to continue the crackdown on Russia’s shadow fleet, as well as combating sanctions’ circumvention. The lack of official data makes it difficult to quantify, but the cost of creating sanctions-busting networks, higher costs on shipping and commodity trading, higher currency and financial transaction costs, and payments of premiums or discounts on resources and goods are estimated to cost the Kremlin billions of dollars annually. “Many observers have accepted the lazy narrative that the sanctions imposed on Moscow at the start of the war didn’t work, and that its economy is humming along. In fact, sanctions inflicted significant damage and reduced the Kremlin’s room for policy manoeuvre, and now Russia’s economy is dangerously distorted as the costs of the conflict pile up,” wrote Bunzel and Ribakova in Foreign Affairs.

The way Russia could play it would be a small incursion, and NATO would be forced to respond, and you would probably have a split among NATO members…”

– Jonathan Terra, political scientist and former US diplomat and NATO analyst

Externalities in Syria and Belarus: The sudden collapse of the Syrian regime and flight of Bashar al-Assad to Russia was a huge blow to Russia’s international credibility. Russian personnel remain in the country’s military bases in Tartus and Hmeimim, though there remains confusion about the status of these under a post-Assad government. Of further concern for the Kremlin was the presidential election in Belarus on January 26, 2025, with President Aleksandr Lukashenko looking to secure a seventh straight term. A loss of Belarus to democratic forces would be another huge blow to Putin personally; to paraphrase Oscar Wilde: To lose one dictator pal may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness. Reaction to what was another painfully obvious rigged election by Lukashenko has so far been muted, with no resumption of the mass street protests that greeted his previous ‘triumph’. Russia has already failed in its effort to prevent Moldova’s further slide towards the EU when the pro-European incumbent Maia Sandu defeated rival Alexandr Stoianoglo in a run-off presidential election in November, despite spending tens of millions to prevent such an outcome.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News