BRUSSELS – Despite domestic political turmoil, Ankara’s timing to pitch closer ties with the EU and win access to the bloc’s defence funds couldn’t be better.

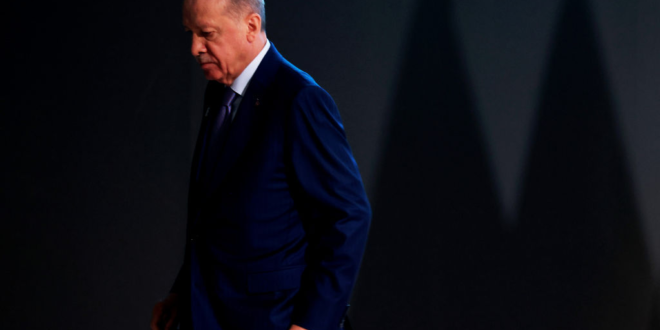

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has chosen his moment well.

Faced with mass protests over the jailing of popular opposition leader Ekrem İmamoğlu, he is doing what authoritarians do best: seizing the geopolitical shift to quench the democratic opposition at home and try to score geopolitical brownie points abroad.

For years, Ankara’s relationship with the EU has been a strained one – particularly due to tensions with Greece and Cyprus, but also due to concerns over Erdoğan’s authoritarian turn, which had frozen the country’s prospect of closer ties with the bloc.

But as the European Commission decided to open the door for some third countries— including Turkey, the UK, and Norway—to collaborate more closely with the EU on its brand-new €150 billion defence programme, Security Action for Europe (SAFE), Ankara has spotted an opening.

Due to arch-foes Greece and Cyprus, Turkey’s recent drive to win access to the EU defence funding is facing two familiar hurdles. Thanks to them, after all, it has never been included in any of the bloc’s initiatives requiring unanimity.

But the return of US President Donald Trump and geopolitical shifts have changed the perspective on closer ties with Ankara, several EU diplomats said.

Over the past few weeks, Turkey has been increasingly involved in European security summits and senior officials have made clear they are interested.

A recurring narrative in Brussels power corridors is now, again, that Turkey remains a like-minded partner and an ally, and long-term security interests should trump the short-term interests of a few.

Turkey’s leverage

Ankara understands well it is needed for Europe’s defence plans.

Just like in the past, Erdoğan knows he has all the pressure points and might be willing to use them, as he did in the past with the EU-Turkey refugee deal, and most recently by striking a bilateral refugee pact with Italy.

This time around, the deal could entail closer defence and economic cooperation with the EU in return for regional security.

After all, Turkey does have NATO’s second-largest standing army after the United States. NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte has reportedly lobbied the EU to seek closer cooperation with Erdoğan.

Ankara has in the past faced closed doors to a project that would improve military mobility of troops and equipment across Europe and North America, which would require unanimity.

Turkey’s strategic geographic location makes it key to controlling the Bosporus Strait, a significant shipping and trading route ensuring access from the Black to the Mediterranean Sea, which it did not hesitate to close to Russian warships early on in the first days of the war.

If, in the future, there would be a need for European warships to access the Black Sea, Ankara holds the key. A permanent Russian Crimean Peninsula, whose native Crimean Tatars had a string of historical ties to the Ottoman Empire, might not be in its interest.

Turkey’s army manpower could also come in handy should any future Ukraine peace deal include European peacekeepers securing a ceasefire.

Ankara already said it would be ready to send peacekeeping forces to Ukraine after already having played a significant role in playing a successful mediator role in the Black Sea grain deal.

According to EU diplomats, Turkish military equipment is among the cheaper options that can be acquired outside the bloc and has been tested on the ground in war zones, including in Ukraine and Azerbaijan.

Among the more significant products is the Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drone system, which is one of the most widely purchased from Ankara across the region. With Turkey’s first domestic fifth-generation warplane project, KAAN, Ankara also looks to replace its ageing US-manufactured F-16 fighter jet fleet.

Turkish defence products are already being procured on a significant scale by some Southern European countries Spain and Portugal, as well as Eastern European countries such as Poland, Romania and Estonia.

Devil in the details

As for access to EU defence funding, an increasing number of EU diplomats believe it is only a matter of time before Europe will have to look reality into its eyes and expand its base of partners to replace US reliance.

One EU diplomat said that the EU “at some point, needs to arrive at a pragmatic assessment of the situation that we need those countries and their industries if we’re serious about rearming fast.” Such views are increasingly echoed around Brussels.

Despite France’s ‘Buy-European approach’ on defence, “on the contrary, we’re moving closer on defence to all those countries,” an EU official told Euractiv.

The sentiment is increasingly shared by a number of EU member states that argue there could be ways to contain long-standing grievances by Greece and Cyprus.

Participation of third countries in SAFE hinges on whether they can secure a security and defence agreement with the EU – which neither the UK nor Turkey have.

A defence industry trade deal, meanwhile, would only need a qualified majority of member states to pass, meaning Greece and Cyprus, who have traditionally opposed Ankara joining any European defence and security-related schemes, could be sidelined.

The latter would be signed directly between the third country and the European Commission, according to the draft text tabled earlier this week, which now can be amended by member states to further tighten – or loosen – the requirements.

If the tides on Turkey turn, the Polish EU presidency could abandon the search for a unanimous consensus in favour of a swifter agreement, some EU diplomats say.

That Turkey has walked a tightrope between aligning with the West over Russia, seems of secondary concern.

Ankara has not joined Western sanctions against Moscow in response to its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, keeping its strong economic and energy ties very much alive.

Turning a blind eye

Erdoğan’s authoritarian turn, which has accelerated before the next Turkish presidential elections, could be a key obstacle to closer ties.

But Brussels might also not be able to afford to put Turkey off.

The recent arrest of opposition Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, days before he was due to be selected as a presidential candidate to challenge Turkey’s incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has raised eyebrows with EU leaders.

But despite German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s sharp criticism, German officials were quick to stress that Berlin would not stand in the way of closer defence cooperation. French Élysée officials abstained from public comments.

Senior EU officials called on Turkish authorities to abide by democratic standards, with “respect for fundamental rights and the rule of law” being “essential for the EU accession process.”

But the majority of EU leaders have remained muted in their criticism.

Soon, Brussels might face a balancing act on what exactly they should do with the hot potato once again. Some EU diplomats believe it could turn a blind eye to the issue in favour of strategic necessity.

It looks different with the political gridlock over closer EU-Turkey ties in other fields.

Modernisation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union and visa liberalisation, two key asks of Ankara for years, are highly unlikely to move over lack of reform, people familiar with the talks say.

It would be hard to justify compared to other EU accession countries that have made bigger efforts.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News