As Lebanon and Syria grapple with profound political transformations and the long shadows of conflict, the notion of federalism—a once-taboo idea—is steadily reentering public discourse. But in a region where divisions often take the form of sectarian identity, the question remains: could federalism, or a deepening of cantonal structures, offer a sustainable solution for fragile, post-conflict states like Syria and Lebanon? Or might it simply institutionalize fragmentation and pave the way for a future of inter-cantonal strife?

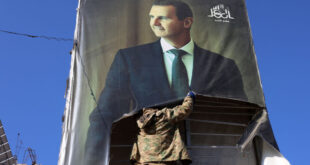

This debate has grown increasingly urgent in the aftermath of recent events—particularly the March 7 massacre of Alawite civilians on Syria’s coast. Such moments have reignited fears of sectarian retribution and underscored the limits of centralized governance in containing violence and fostering reconciliation.

Federalism as a De Facto Reality in Syria

In Syria, federalism appears less a theoretical proposition and more a lived, if chaotic, reality. Years of civil war, demographic displacement, ethnic cleansing, and military fragmentation have divided the country into de facto zones of influence. The geographic distribution of ethnic and linguistic communities, coupled with the enduring scars of violence, has fostered an implicit federal structure—even as the idea remains politically contentious.

While some voices resist the logic of partition, there is a growing, if reluctant, recognition that decentralized or federal arrangements may offer the only path toward a durable peace. However, the risks are evident: if federalism hardens sectarian lines rather than transcends them, it could entrench existing hostilities under new banners.

Lebanon: On the Brink, Yet Not Over

Unlike Syria, Lebanon has not experienced a full-scale civil war since the Taif Agreement of 1989. Despite recurring political crises, assassinations, and sectarian tensions—especially heightened in the wake of the Gaza war and Israel–Hezbollah escalations—the country has largely remained intact. And yet, Lebanon today teeters on the brink of political dissolution, with its sectarian foundations exposed and its institutions paralyzed.

Here, federalism evokes visceral reactions. For many Lebanese, the term is synonymous with partition—a flashback to the civil war and the country’s long history of confessional conflict. The widespread misunderstanding of federalism often leads to its dismissal as merely a euphemism for sectarian division. But the real challenge lies deeper: can any form of decentralization function in a state where corruption is systemic, and political elites operate across sectarian lines to entrench their power?

As critics rightly ask: Would federalism simply empower the same entrenched actors—shifting their influence from the national parliament to regional strongholds—allowing them to control resources and populations more intimately, while further insulating themselves from accountability?

Who Rules the Canton?

The federalism question in Lebanon is not merely about structures of governance but about the identity and motives of those who would wield power under such a structure. If the same political elites remain in control—figures deeply rooted in Lebanon’s sectarian and clientelist order—then federalism may simply become a new façade for old corruption.

Before debating federalism as a technical solution, Lebanon must confront a more foundational question: can a functioning state be built outside the confines of sectarianism? Given the current dominance of Hezbollah, and the historical failure to build a genuinely civic polity, some factions—particularly on the Christian right—have turned to federalism as a defensive fallback, rather than a democratic ideal.

Meanwhile, Lebanon’s secular minority—sometimes called the “nineteenth sect”—remains the most marginalized. Their vision of a pluralistic, citizen-based state continues to be stifled by both the political class and the logic of identity politics.

Federalism or Fortress?

A successful federal model requires trust, institutions, and a baseline of shared national identity. Lebanon has none of these in stable supply. Instead, it has deeply entrenched fears—of Hezbollah’s weapons, of external wars, of the collapse of state services, and of demographic imbalance. Against this backdrop, federalism risks becoming a cover for self-isolation, not a tool for cooperative governance.

Three main concerns arise in the current debate:

Sectarian Entrenchment: A federalism framed by sectarian affiliation risks institutionalizing division, not bridging it. Without mechanisms for cross-sectarian dialogue and shared governance, the system may exacerbate fragmentation.

Miniature Autocracies: There is a legitimate fear that federalism could empower local strongmen, replicating the failures of the central state at a smaller, more authoritarian scale—particularly in a system already manipulated by mafioso networks.

Copying Syria’s Model: Lebanon cannot blindly mimic the Syrian context, where federalism emerged from armed conflict, vast territorial divisions, and ethnic disparities. Lebanon’s geography is small, its cities diverse, and its cultural intermingling far deeper than its politicians admit.Another danger lies in sidelining Beirut—Lebanon’s historically cosmopolitan heart. Dismantling the symbolic and practical role of the capital in favour of rigid sectarian cantons risks undoing one of the country’s few unifying civic spaces.

Decentralization: A More Viable Path?

Alongside the federalism debate, a more pragmatic conversation is emerging around decentralization. Unlike federalism, which implies formal redistribution of sovereign powers, decentralization focuses on administrative efficiency and local governance. With more than a thousand municipalities already functioning—many with strong community ties and operational capabilities—decentralization offers a more natural evolution of Lebanon’s governance model.

Indeed, municipalities have proven essential in service delivery, particularly in times of crisis, and are now central to discussions around reconstruction and development. But even decentralization is not immune to political sabotage. In regions like Jabal Amel, where Hezbollah’s influence is strong, municipalities often operate under tight security constraints. Real authority, especially over policing and public safety, remains in the hands of the party—not the local councils.

Security Before Structure

The core obstacle to both federalism and decentralization in Lebanon is not technical—it is security. No governance reform can succeed in a country where military power is fragmented, where militias operate outside state control, and where the rule of law is selective.

Until Lebanon resolves the fundamental question of who controls its arms, its land, and its borders, all constitutional models—federal, decentralized, or otherwise—remain vulnerable to subversion.

A Path Forward?

Lebanon and Syria stand at parallel yet diverging crossroads. In Syria, federalism may be a fact before it becomes a choice. In Lebanon, it is a choice haunted by history and loaded with unresolved fears. What both countries share, however, is a desperate need to move beyond sectarianism, to rebuild trust in public institutions, and to reimagine what shared citizenship might truly look like.

Whether through federalism, decentralization, or other hybrid models, no structural solution can substitute for the deeper transformation that is required: a transformation of political culture, public accountability, and social imagination.

Only then might the Levant—fractured, battered, and resilient—find a path out of perpetual crisis and toward something resembling peace.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News