The French, deeply attached to republicanism, have divided their modern history into five distinct republics, each marked by a significant historical turning point. In our view, this tradition reflects their desire to compensate for their brief and unsuccessful attempt to restore the monarchy between 1870 and 1883—an era commonly associated with the so-called French Third Republic.

As with many French political customs, this model has been adopted across the world, including the Arab world, where historians—particularly since the Arab Spring uprisings—have grown increasingly inclined to segment their countries’ histories in similar ways.

The expression “Third Republic” has thus taken on political meaning across the region. In Egypt, it has been used to describe the era following Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s rise to power. In Tunisia, it serves as shorthand for the period after Kais Saied’s constitutional coup. Notably, a political party named “The Third Republic” was even established in Tunisia, whose slogan—“If you want to change the system, you must enter it”—reflects this new political lexicon. In Tunisian dialect: Bāsh nbadlou el-system, lāzem ndkhlou fih.

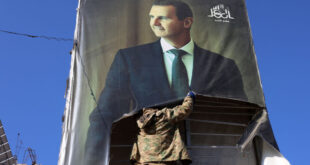

In Syria, the term “Third Republic” has been invoked to describe the country’s future after the fall of Bashar al-Assad. Yet, in our view, this usage reveals a certain eccentricity long characteristic of the opposition to the now-defunct authoritarian regime. Its oddity lies in the fact that it describes something that has not yet occurred. For this term to be useful and meaningful, it must be transformed from a mere descriptor into a tangible political project—one with vision, structure, and ambition. In short, it must acquire a political meaning grounded in a forward-looking framework: a Third Syrian Republic Project.

The Assad regime fell on 8 December of last year. Yet to this day, no serious political vision has emerged to bury its legacy—neither from the new authorities nor from their opposition. There appears to be little real will to embrace a project for a Third Syrian Republic.

We believe a political project is only valid if it is also a social and economic one. It must be close to the people it claims to represent, responsive to their needs, and articulated in accessible language—not simplistic, but free of unnecessary complexity. Clarity does not preclude depth of theory.

Opposition politicians in Syria should not fear outlining their vision for how they would govern, should they come to power. This is not utopian thinking. On the contrary, the essence of politics—and of political parties—is the aspiration to govern. In today’s Syria, presenting a comprehensive solution under the banner of “The Third Republic Project” would, at the very least, allow Syrians to engage with an alternative vision—one that departs from the dominant paradigms that have driven them to despair and apathy.

We propose that this project rest on the following key pillars:

The unity and sovereignty of Syria: The Syrian state must be built on its internationally recognized borders. Without clear borders and sovereign control, the concept of a state becomes meaningless. And without a meaningful state, no political project, slogan, or vision can be sustained.

Separation of powers and non-discrimination: The fundamental constitutional question is not the religion of the state or its president, but the establishment of a framework that guarantees checks and balances. We should avoid falling into endless, unproductive debates about secularism versus Islam. While secularism is our principle and ideal, it should not become a sacred symbol that obstructs dialogue. Core symbols of statehood—its name, language(s), religion, and flag—should be decided by a post-transition parliament. Until then, we must hold firm to our principles in preparation for potential negotiations. This is not a concession, but a strategic posture.

Recognition of Syria’s diverse ethnic fabric: A people, by definition, share common cultural customs and ethnic identity—not necessarily a religious or sectarian one. Non-Arab Syrians must be recognized and granted full cultural rights, particularly the right to speak and learn their native languages openly. While this recognition may raise concerns about self-determination, the current realities suggest that no Syrian faction can achieve full secession. At most, local autonomy may be pursued—an arrangement that does not undermine national unity, provided individual rights remain protected and citizens can seek justice in national courts if wronged.

Constitutional foundations: The above principles should be enshrined in a set of clear, foundational constitutional norms—especially during the transitional period. These principles should serve as the basis for a shadow government or shadow parliament. They must be few in number, clearly stated, widely understood, and amendable only by a two-thirds majority. We reject the notion of “supreme constitutional principles,” which contradicts constitutional jurisprudence and have no precedent elsewhere. Egypt’s failed attempt to implement such a framework after the 2011 revolution stands as a cautionary tale.

Addressing the sectarian question: Sectarianism must be tackled calmly and practically. The language of hatred must be confronted wherever it arises. Equal citizenship must become the foundation of national identity. In a democratic process, “majority” and “minority” are political—not religious—categories. Candidacy for public office must not be based on sectarian affiliations. We must therefore reject both consociational democracy and the replacement of democracy with shura. The reintroduction of a Senate could provide a reasonable mechanism for sectarian representation within the framework of transitional justice.

The social justice state: A viable socio-economic model for the future must embrace both social justice and liberalism—properly understood. Liberalism does not mean a withdrawal of the state, as neoliberal ideologues claim. At its core, liberalism requires a strong, capable state—one that can provide health insurance, guarantee quality education, prevent monopolies, implement a fair labour law, set minimum wages, and combat tax evasion. There is no contradiction between liberalism and social justice. Housing, education, and healthcare must be constitutional rights for all Syrians.

Foreign and regional relations: Syria’s foreign policy should be based on rationality and mutual interest—including, controversially, with Israel. We believe in a “zero-problem” approach to regional relations. However, in the case of Israel, normalization cannot proceed until outstanding issues—including crimes and occupied territories—are addressed and resolved.These are some of the elements of a political project for a Third Syrian Republic. With open discussion and constructive engagement, we believe this can evolve into a coherent, actionable political vision.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News