- Introduction

For decades, the international system was characterised by the hegemonic position of the US, consolidated after World War II and strengthened after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991. However, China’s re-emergence as a key player in the world’s economic, political and military dynamics has started to challenge US primacy, something that began to become evident in Donald Trump’s first Administration in 2017 and has intensified since his return to the White House.

In the few months that have elapsed since his return to power, there has been a radical change compared with previous Administrations, both in terms of rhetoric and in terms of economic and foreign policy. His protectionist policies, his withdrawal from global commitments and the imposition of tariffs on allies and rivals have caused acute uncertainty, while his foreign policy decisions have become increasingly reminiscent of the gunboat diplomacy of the 19th century.

The ‘America First’ rhetoric and his conviction that the liberal order’s rules and institutions –the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank– have militated against US interests are creating a disruptive dynamic inimical to the old international order. It is an order that has perished –as the US Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, asserted at his Senate confirmation hearing– despite the fact that its replacement has not yet fully emerged. But it can be discerned. It is uncomfortably reminiscent of the historical concept of the ‘Thucydides Trap’: a dominant power in decline fears the rise of an emerging power and instigates a strategy of decisions and actions leading to considerable tensions within the system, the final outcome of which is by no means clear. The only certainty is that there will be winners and losers in the process, and that all the participants will be obliged to scrutinise their strategies. It is always possible to fall victim to the ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’, whereby a series of actions and reactions leads to a state of affairs in which everyone loses.

- The contemporary ‘great game’: more than two players

The central question posed by this analysis is: how are countries –especially those that have been historically allied to the US or taken a neutral stance– going to respond to an international order in transformation and undergoing growing economic and geopolitical instability?

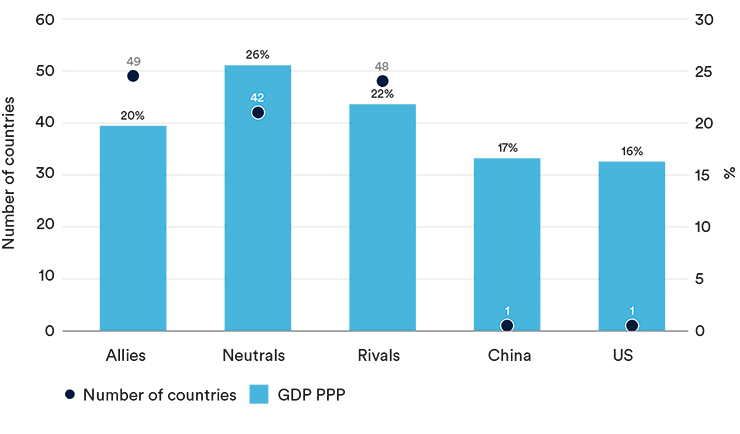

To address this question, a model drawn from game theory will be employed involving the following players: the two hegemonic powers (the US and China), the bloc of countries allied to the US, China’s allies –referred to as the ‘rivals’– and the non-aligned or neutral countries. In order to assign countries to each bloc, countries are defined as ‘allies/rivals’ depending upon whether they have systematically voted for or against US stances at the United Nations, and as ‘non-aligned or neutral countries’ if around half the time they have voted with the US and the other half against it.

Figure 1. Countries and blocs: number and share of global GDP (US$ at PPP)

For each bloc of players an extensive economic, financial, military and soft power database has been built which will help to quantify the impacts of the alternative strategies available to the participants in the game.[1]

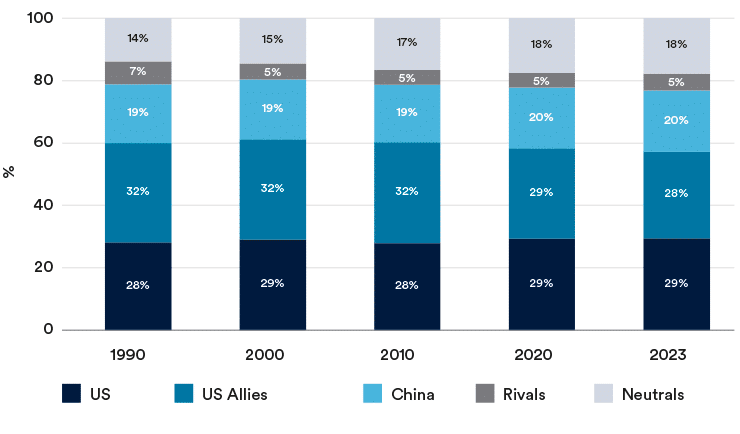

For now, to gauge each bloc’s foreign influence at the outset, Figure 2 shows each bloc’s score in the Elcano Global Presence Index.[2] In order to aid understanding, the figure of 100 is used for the most recent score available in the global index, so the data are interpreted as the share of foreign presence that each country has in the index. It is important to emphasise that the index measures neither size nor power but something else: how each country projects itself abroad in economic, military and soft-power terms.

Figure 2. The Elcano Global Presence Index: relative shares

Some pertinent conclusions may be drawn from Figure 2. The first is that there is still a significant gap separating the hegemonic powers: the US not only leads the ‘global order’ by almost 10 percentage points –scoring 29% to China’s 20%–, it also occupies the leading position in the three components of the index. In the economic and military indexes it has a twofold lead over China, while in soft power it has a lead of eight percentage points. The second is that the preponderance of the US’s allies is virtually identical to that of the hegemonic power: 28% compared with 29% for the US. The numbers underlying this ‘tie’ are revealing: it is based on a very pronounced US hegemony in the military and soft-power components. In the economic component, the allies have a greater presence than the US. The third observation is that China’s allies –the rivals– occupy a very low position in the Elcano Global Presence Index: barely one fifth of China’s. In other words, they are allies with a ‘weak’ external presence in absolute terms and even more so in comparison to the US’s allies. Lastly, the neutrals are far from being strategically negligible: they almost equal China in weight and account for more than half of the US’s share. If they were added to the US’s allies, they would form a bloc with the same weight as the two hegemonic powers combined. The likelihood of this arising is highly remote of course, because it would require a governance structure capable of corralling a coalition of more than a hundred countries.

- The clusters of geopolitics

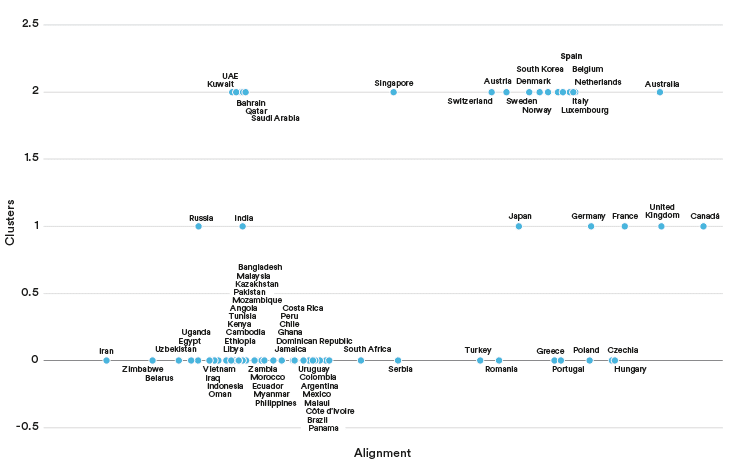

In order to validate the membership of the various blocs that emerge from analysing UN voting patterns, an econometric model was used to estimate the elasticities of each country’s Elcano Index score relative to the variables chosen in order to assess its economic prowess, its openness to the outside and its military and soft power. The groupings that emerge from the analysis of UN voting patterns have been validated using clustering techniques, given that the correlation between the two hierarchies is virtually 100%. The three clusters that have been detected are shown in Figure 3. The horizontal axis represents the degree of alignment with the US vote at the UN using an indicator that integrates the coincidence and the persistence of such positioning, while the vertical axis shows membership of one of the three identified clusters.

Figure 3. Clustering the Elcano Global Presence Index: Elcano and the military and economic dimensions

Occupying the upper part of Figure 3 (cluster I) are countries that combine significant economic capability with considerable military prowess or, in some cases, a notable profile of geopolitical influence. They include, clearly differentiated in the upper left-hand section, the Persian Gulf countries (Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait and Bahrain) with considerable economic resources and a growing military and security presence. Also notable are highly developed European nations such as Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, Sweden and Spain, together with robust economies such as Singapore and Australia. To a large extent this cluster comprises solid economies underpinning active defence policies or countries wielding significant influence in international affairs.

The second cluster, occupying the central section of the Figure, includes the traditional powers: the UK, Germany, France and Japan. These nations are characterised by their combination of substantial economic prowess with consolidated defence institutions and a history of leadership in multilateral organisations. Russia and India are also included in this second cluster occupying intermediate positions, reflecting the fact that, although they wield considerable military strength and significant economic weight, their situation on the left of the Figure shows their non-alignment with the US. In the original classification, India was categorised as a neutral, non-aligned country, and Russia as one of the cornerstones of the rivals.

Appearing in the lower section are the emerging countries with medium-sized or growing economies, and with military and defence structures of regional significance. This comprises a varied group ranging from Latin American countries such as Mexico, Colombia and Chile to African countries such as Egypt, South Africa, Ethiopia and Nigeria, and including such Asian countries as Pakistan, the Philippines and Indonesia. Although it is a heterogenous cluster its members share the fact that they are in the process of diversifying their economies and enhancing their international importance, whether at the economic or geopolitical level. Those located furthest to the left constitute what are being referred to as the rivals, with the more neutral countries appearing in the more central section of the Figure. The right-hand section includes such allies as Poland, Portugal and the Czech Republic.

- Game theory and hegemonic powers

The current geopolitical rivalry between the US and China is perfectly suited to analysis by game theory. The ‘game’ in this case is a non-cooperative one, which unfolds sequentially and where at every turn each of the protagonists seeks to maximise its rewards and minimise its losses. It involves assuming the rationality of all the participants. Each player has a finite number of strategies and, as the game unfolds, the players reveal their strategies simultaneously or sequentially. Given the evident fit between this analytical framework and the current geopolitical situation, a model has been devised featuring an iterative, zero-sum game in which the strategies of the US and China change over the course of their interactions in response to the opponent’s conduct.

‘Victory’ is defined as an equilibrium in which China secures a ratio of approximately 1:1 relative to the US in the Elcano Global Presence Index compared with its current 0.6:1 ratio. The goal of the US is to avoid this and to maintain its leadership. In this context, it is assumed that the hegemonic powers can adopt three strategies:

Cooperate, the strategy that prevailed in the world up to the first Trump Administration.

What shall be referred to as MAGA, which consists of turning inwards and harnessing all resources to redirect them towards the strengthening of domestic capabilities.

Confrontation between hegemonic powers, which is the level following the MAGA strategies. Confrontation entails the two powers closing themselves off to each other and cancelling their economic transactions.

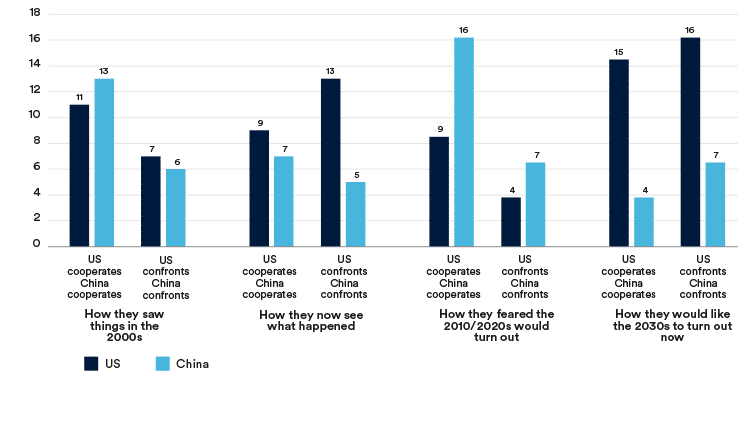

With the help of the estimated elasticities in the econometric model, an ‘imaginary’ matrix of the playbook that appears to underlie the MAGA movement is constructed. Figure 4 summarises the results obtained and offers a solid –and rational– explanation of why the US has chosen to blow up the old world-order from the inside.

Figure 4 shows the matrix of transactions between China and the US at two moments of time. The dark blue columns show the ‘tolls’ exacted by the US in the various alternative strategies and the light blue columns the tolls exacted by China. The numbers show both countries’ respective growth in the Elcano Index relative to the preceding period.

Figure 4. The US and China: reality and perceptions of yesterday and tomorrow; the US before and after MAGA

‘How they saw things in the 2000s’ shows the matrix of transactions the US then thought stemmed from its decision to support China in its integration into the global economy by offering cooperation and its admission to the WTO. The conclusion to be drawn from the figures here is this: the US accepted that by cooperating with China, the latter would improve its position in the Elcano Global Presence Index by 13%, an increase that exceeded what they themselves would achieve: 11%. Even so, it accepted this shortfall not only as a matter of principle but because, if it confronted China, the benefits it would obtain (7%) would be lower than those arising from a cooperation scenario. For the impact on the US’s own index score, the trade-off between cooperation and confrontation was high. Cooperating secured an improvement of 57% and the ‘toll’ it paid for facilitating rapid growth in China’s index score was low: the China/US ratio of growth in the cooperation scenario was 1.18 while in the confrontation scenario it was 0.85, a difference of 0.3 points, for which it received an improvement in its index score of four points (the difference between 7% and 11%).

‘How they now see what happened’ reinterprets that era from the MAGA standpoint. First, the benefits of cooperating, both for the US and for China, are dramatically reduced, which is consistent with the MAGA movement’s distrust of the advantages of trade. Rather than growing by 11%, the US now grows by only 9% and instead of growing by 13% China secures only a 7% increase. How this matrix of retrospective and ‘revised’ tolls fits with reality as measured by statistics is a mystery, but not the most important point: what matters is the message contained in the next two columns, which reveal that if the US had engaged in confrontation it would have done better (going from 11% to 13%) and China much worse (13% to 5%), confirming what MAGA has always thought, that confrontation is better than cooperation.

‘How they feared the 2020s would turn out’ is covered by the next four columns. Maintaining cooperation would have led to greater asymmetry in the distribution of benefits from this ‘do-gooder’ strategy: the US would have increased by 9% compared with China’s 16%. The reason suggested by the model is that China was ‘cheating’ them because instead of being a partner loyal to the system it was ‘piggybacking’ on its rules: it exploited them in its favour but did not submit to their obligations. The asymmetry between the benefits it was deriving and the costs it was bearing was enabling it to close the gap in its global presence compared with the US at such a speed that in two or three decades it would end up becoming the undeniable hegemonic power.

The interesting thing about the next two columns is that, with the rules of the old order, confrontation was even worse: both the US and China would lose 56% with the US falling from 9% to 4% and China from 16% to 7%. The implication is clear: confrontation alone is not enough, there was also a need to change the rules of the game.

This is what the last two columns represent: ‘How they see the future’. With the new international order being devised in Washington, the US will once again be a strong leader –growing by 15%– and China a rival that will increase by only 4%. This is in a cooperation scenario, because if what finally prevails is a confrontation scenario – as seems likely – the US hastens its progress and, paradoxically, China, which will have to turn to its allies, the neutrals and perhaps the US’s ex-allies, will succeed in advancing more rapidly because it is the latter it will ‘cheat’ or from whom it will derive ‘rent’ in the classical sense of that term.

There is another reason to explain why the US decided to switch to MAGA. This is what in game theory is known as the ‘shadow of the future’: the expectation that the strategic game unfolds over various rounds and thought has to be put into how the incentives and costs of each strategy work out for or against you. When the game is viewed as a slow and predictable process, the discount factor of the future is low: everything can be rectified without ‘errors’ proving fatal. But when the future arrives more quickly, the discount rate rises exponentially and the actions taken now are worth more. In this scenario –similar to the one described by Thucydides in the 5th century BC– prevention is better than cure: if your hegemony is at risk because China can steal an advantage with an economic, technological or military initiative to which you are unable to respond, the rational option is to act first and to ponder later.

The implications of this simulation are disturbing to those of us who believe in positive-sum games. If undisputed hegemony is the goal of the US, MAGA is more rational than is usually supposed: China loses more than the US. Moreover, the new equilibrium to which it leads is more stable than many of us would want. The reason is simple: the absolute value of China’s losses are less than the relative benefits to the US, meaning that the system as a whole could be –although it is by no means certain– better than in the pre-MAGA world. Although in the event of this difference between benefits and costs being narrow and uncertain, whichever side initiates the game expects that the change of rules and uncertainty will affect its rival hegemonic power and the rest of the world even more than itself. Once this point is reached, the whole world will start to suffer shocks and will have to review its strategies. The game becomes global.

- The other pieces of the chessboard

The question to be put to MAGA advocates is whether their plans envisage that allies and rivals, despite the costs they are going to have to bear, will go on acting in exactly the same way as they have in the past. The answer, from the viewpoint of the countries that constitute the other chess pieces, is unequivocal: it would be an error of judgement if they voluntarily put this forward as their strategic response.

To test this, for the purposes of the model it has been assumed that, while the secondary players are initially dependent on the policies that the US and China impose on the blocs –whether they cooperate with them, isolate themselves from them or confront them– in later phases they theoretically have three alternatives:

Loyalty: this consists of strengthening the ties with the historical hegemonic power, although the latter now requires a greater show of loyalty or may even impose explicit costs on its allies such as tariffs or tributes of servitude.

Untethering: this is basically the European de-risking strategy. The realisation that the hegemonic power is raising the price of belonging to its bloc and that desertion does not entail unacceptably punitive costs leads to a distancing from its sphere of influence. This may be conceived as a version of Strategic Autonomy.

Change: the third would be an extreme option; convinced that the hegemonic power is going to be defeated, exasperated with its demands for tribute and being subjected to arbitrary and discriminatory measures, the only option is to change sides and switch hegemonic power.

While the second option may be thought feasible in the short to medium term, it is unlikely to constitute a stable solution. The reason is simple: the elasticity of exports (0.4) is so high that, without the US and Chinese markets, maintaining the same levels of global presence and prosperity is highly improbable.

‘Fortress Europe’ has not been considered as an option. In order to continue being Europe –with its values– the bloc needs to be in the world and there is only one path to this without the hegemonic powers: strengthening alliances with the neutrals. Calling this scenario a ‘third hegemonic power’, in other words Europe’s transformation into the third giant of the league in terms of global presence, is a wild exaggeration born of wishful thinking. But it makes sense to think about it within the context of the model as a long-term option, if only to make it clear that it is a superior strategy to switching hegemonic power and choosing China.

5.1. The allies’ strategy

The shocks have been gauged in terms of the volatility of the variables that are going to be used as the channel of transmission of the disturbances to which the model is going to be subjected. These variables –in other words, the rate of variation of these variables, given that the model is based on logarithms– are GDP, defence spending, exports and soft power. The variable that changes as a consequence of these shocks is the Elcano Index for each of the blocs or hegemonic powers. All these impacts are estimated with the help of the previously calculated elasticities.

If they face a low or medium-strength shock the allies –specifically the Europeans– envisage the loyalty strategy having unequivocally negative effects on GDP and the foreign sector. That said, it is possible for all or some of these costs to be lower relative to those generated by alternative strategies by standing by the traditional hegemonic power. The condition needed to enable this outcome is for the hegemonic power to decide to be benevolent and help to offset part of the costs. A possible route involves ensuring access to its technologies, but the most decisive involves renewing its defence and security pact. As the estimated elasticities suggest, this factor is the one that has the largest negative impact on the allies’ position in the Elcano Index: every 1% increase in military spending causes a 0.5% fall in the Global Presence Index. Therefore, if it is not necessary to invest in defence because you are ‘piggybacking’ on your protector’s spending, remaining loyal can be a rational strategy, although it can induce an emotional and reputational fallout; even more so if these savings enable you to maintain or increase social spending, reduce taxes and improve the medium-term sustainability of the deficit and internal debt. Domestic cohesion can be easier to maintain.

This type of loss-minimisation also brings two other advantages: ensuring that there will be no calamities and above all avoiding the need to incur the costs of adapting to a new model. The cost is also obvious: increasing your dependency on a hegemonic power that is liable to modify the rules in an unexpected, arbitrary and non-negotiated way. The net impact of the postulated shocks on GDP, exports, defence spending and soft power is a fall in the allies’ Elcano Index position of 1.4%, exceeding the falls registered by the two hegemonic powers: 0.7% for the US and 1% in the case of China.

Although the model predicts that the global shocksproliferate in the case of the allies, this does not apply to either the neutrals or the rivals: the neutrals because they can continue relying on their exports and the rivals because they can transform the global shock into impetus for their global presence, thanks to their ability to leverage the growth of the hegemonic power with which they are aligned.

If the allies opt for their strategic autonomy and gradually untether themselves from what had formerly been their protector, the scenario has both economic and security implications. The economic consequences arise in two spheres: reduced access to the hegemonic power’s market means a negative shock for its exports which, in turn, translates into a larger fall in GDP, which has been exogenously inserted into the model.

Moreover, for the untethering –the de-risking– to be credible, there is a need to invest in adapting to the new scenario and this will not necessarily reap immediate dividends. The net effect of all this is that GDP shrinks 1% relative to the base scenario and exports twice as much as in the loyalty scenario. But the most important impact is on defence spending and, to a lesser extent, on soft power. The allies now have to start to pay for their defence, which incurs significant costs: a 0.7% fall in the index. In combination with reduced access to the hegemonic power’s technology, the net effect of all the shocks is a fall of -2.6% in the Elcano Index. This value does not mean that seeking autonomy is a worse strategy than remaining loyal, by any means. What it really means is that there are sunk costs in the strategic turnaround because they do not have an immediate alternative for replacing the US market with another market.

Indeed, the lesson that can be drawn is that a ‘Fortress Europe’ is costly in both economic and defence terms. The Single Market is of insufficient size to sustain the EU’s levels of welfare and income. To ensure this objective, it is necessary to secure new trading and financial partnerships, and to continue the process of internationalisation.

Hence the third option: approaching the neutrals and trying to formalise a closer alliance with them, one that in the long term may end up emerging as a new hegemonic power –a sort of third way–. This is a distant prospect because there is no governance structure capable of managing a federation of more than 50 highly heterogenous countries. But the incentive of gradually moving towards such increased cooperation is considerable: the potential effect on exports is very positive, while reducing the negative impact on GDP by half. These two effects would enable the comprehensive investment in security and defence to be financed. The net effect of this alternative strategy, although not feasible in the short term, makes it the only positive scenario of all those envisaged by the model: a 0.6% increase in the Elcano Index.

The worst option is changing the hegemonic power: replacing Washington with Beijing. The reason is that the positive effect of exports and soft power –through accessing the new hegemonic power’s technologies– would not be sufficient to offset the significant costs incurred by adapting to the hegemonic power, which are estimated at -1.6% of GDP and -1.7% in defence spending. The net fall in presence –2.8% percentage points– is the highest generated by the model.

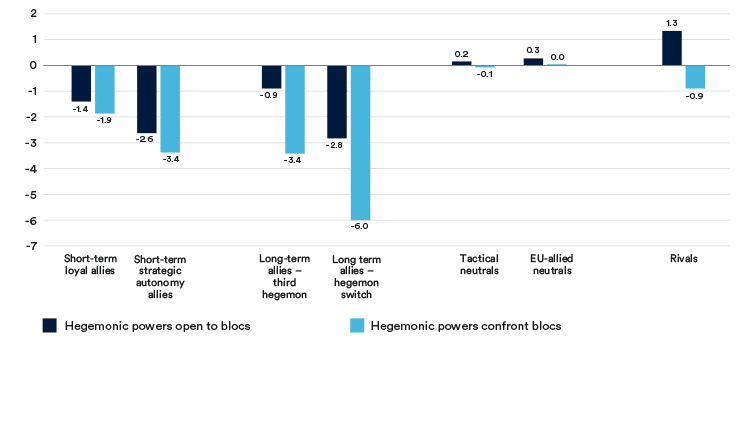

Figure 5 sets out all the scenarios of the simulation that has been carried out. The dark blue columns show the scenario in which the hegemonic powers are disposed to cooperate with the rest of the players. The light blue columns show the scenario in which the level of tension between them rises to the point where both decide to focus on themselves and they ignore or shut out the other players, including their allies. The latter is the scenario of everyone against everyone.

Figure 5. A negative-sum game for the blocs

5.2. The neutrals’ strategy

The neutrals have two options: remaining equidistant between the hegemonic powers and behaving tactically by approaching those players that offer the greatest advantages, or foreseeing that bipolar worlds will always be to their disadvantage and that it is preferable to start building a stronger relationship with the former allies of the US.

In a world of moderate shocks to GDP, defence spending, exports and soft power –in other words, with volatility of less than 1.5 standard deviations in these variables– both options yield similar results, so unless strong incentives emerge for cooperation with the ‘political orphans’ it is unlikely that they will move in this direction. The past persists and the Europeans are the recipients of too much recrimination –both historical and recent– for the equilibrium to shift towards open cooperation, unless considerable political leadership and bravery is shown on both sides. The Europeans’ negotiating carrot would need to involve offering neutral countries preferential access to the European Single Market so they can be sure of making headway on GDP and external markets.

In all the scenarios studied, the rivals take advantage of maintaining cooperation with their hegemonic power, China, and live in an apparently placid and stable world: their global score rises by 1.3%. If the hegemonic powers turn their backs on cooperation with the blocs, the outcome is catastrophic for allies and rivals. Their losses would spiral because the compensating effects both of opening up and of soft power would evaporate and they would have to bear the costs of defence spending and a shrinking GDP alone. As previously mentioned, this is the scenario represented by the dark blue columns in the Figure. In a world of severe or drastic shocks, the dominant strategy is highly likely to be that of confrontation between hegemonic powers and between the latter and the rest of the world: a scenario pitting everyone against everyone. It is preferable not to analyse it and trust that we never see ourselves facing it. It would be a world that we did not recognise and in which many would probably not like to live.

- The optimism of goodwill

The simulation exercise that has been conducted does not presume to prophecy what, at such a convulsive and uncertain time as the present, may take place. It seeks only, in a simplified way, to outline scenarios and to analyse the consequences that may stem from the strategies that are currently deemed to be possible. No more than this.

The analysis confirms the instability of the global order and the difficulty of returning to the previous (post-Cold War) situation. The protectionist rhetoric and the trade war instigated by the US have been a blow to multilateralism, but such a withdrawal also incurs risks for US hegemony itself: it opens the way for China to occupy vacated spaces and attract trading partners anxious for an alternative market.

In the present author’s opinion everything stems from a partial and grotesquely simplified reading of reality, fatefully leading to the conclusion that the rules of the system, devised by the hegemonic power itself, are being used against it, not only by the rival power in the ascent –China, a country perceived to have always cheated and has de facto piggybacked on the system– but also by its own allies. Once this conclusion has been reached, the only solution is to blow up the system from within.

The non-cooperative game scenarios can lead to sub-optimal outcomes for all parties. Even so, the uncertainty works in favour of the US to the extent that it can force its allies to follow it, for fear of the costs of deserting. For China’s part, if it fails to manage its vulnerabilities properly it could see itself harmed by reprisals, financial restrictions and setbacks to the free trade that has underpinned its growth.

Europe has launched strategic debates about defence spending and technological autonomy, given that dependency on the US in both areas reduces its room for manoeuvre. The realist option of total independence is fraught with difficulty, but there is scope for improving the negotiating position by increasing cooperation with neutral countries and seeking an intelligent diversification of markets.

The existence of limitations in the methodology used is not fatal to the goal that has been pursued from the outset: that of trying to marshal the debate and the accounts that will inevitably dog us over the coming months, if not years, with the aid of rigorous analysis and data.[3]

The only things of which we can be certain is that we are witnessing a profound change in the international order and that this change is complex, incurs risks and has consequences not only for our per capita income and rate of inflation, but also –above all– for democracy, freedoms, the internal stability of political systems and, in short, for the values of all the world’s societies.

The game theory model and the data that have been derived from it here confirm that the risks and potential changes are manifold and have costs that will not be distributed symmetrically: there will be winners and losers, not only among countries but also within countries. If they had to be summarised it would be worth highlighting four points:

The US’s structural advantage. Its self-sufficiency in energy and the centrality of its financial system give it a superior ‘power of negotiation’ to impose tariffs or obstacles to accessing its market.

The Chinese dependency on supplies and energy. Despite its extensive manufacturing base, China has up to now depended on importing considerable quantities of raw materials and technology, which forces it to nurture relations with its allies and above all with allies of the US and neutral countries.

The role of neutral countries such as India and emerging Latin American powers. They could pivot between one bloc and another as it suits them, thereby generating ‘support-buying’ incentives on the part of the hegemonic powers or forming their own alliances with regional powers.

The discernible costs for Europe. The EU, as the main bloc of allies, faces an uncomfortable dilemma: continuing under the security umbrella of the US with little scope for negotiation or embarking upon a course of strategic autonomy with the consequent considerable implementation costs.

Game theory offers an analytical framework conducive to the analysis of these behaviours because it focuses on studying non-cooperative scenarios in which the participants lack full information about what the other players are going to do. The models can also take account of successive iterations that enable the participants to change their strategies. This is exactly what should be expected to occur: we are only at the start of the contest and in the months ahead we are going to see how the cards are dealt and how fresh hands are played. Everything is accompanied by a good deal of uncertainty, fear and risk.

But it will pass, and the future will show that Europe has the resources, the know-how and the historical legitimacy to take part in the construction of a more balanced and sustainable international order. The question that we Europeans have to ask ourselves is not whether we should embark upon this transformation but when we should start and how we can implement it in the most effective way possible.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News