In December 2021, United States intelligence claimed China was helping Saudi Arabia develop ballistic missiles. Washington feared the Saudis were abandoning them in pursuit of a closer partnership with China. For some US policymakers, this pointed to the growing threat of China displacing the United States as the principal external power in the Middle East.

Such fears were — and still are — overblown. Saudi Arabia and other Arab Gulf states account for a larger proportion of China’s economic relations in the Middle East than Iran. In 2020, China’s trade with Saudi Arabia was worth US$65.2 billion — compared to its trade with Iran of US$14.36 billion — and that gap is growing. But this has not led to any change in Chinese efforts to displace the United States as the dominant global power in the region.

Yet even if China wishes to remain aloof from tensions in the Middle East, it has found it difficult to do so. Non-alignment will only get harder if the underlying rivalries are exacerbated to the point where a regionwide conflict takes place. China has pursued commercial relationships with states across the region, while also recognising the tensions between them, which it has acknowledged mainly through the use of rhetoric.

China notably used the Global Security Initiative to encourage Middle Eastern countries to create their own regional security architecture — making it clear that it favoured any security initiative to come from inside the region without the involvement of outside forces. This was a tacit rejection of the United States’ presence, but there is little indication that China wants to take on a more active role as a conflict mediator between Saudi Arabia and Iran, or use the position of one against the other.

Though there is a disparity between China’s influence in Saudi Arabia and Iran, China’s involvement in the Saudi missile program does not represent a substantial shift that could destabilise the Middle East. A longer-term perspective is needed when it comes to evaluating China’s relations with the Gulf.

The missile trade between China and Saudi Arabia is not new, having started as early as the 1980s. When the United States refused, China sold Saudi Arabia 25 medium-range ballistic missiles in the wake of the Iranian revolution and the Iran–Iraq war. As Saudi Arabia has not used the missiles, the purpose of the current Saudi missile program may be for deterrence rather than offensive use.

Whether Saudi Arabia chooses to use the missiles is arguably separate from China’s involvement. Beijing has historically been an arms supplier, albeit a secondary one, for countries in the Middle East, including Iran. China’s more recent assistance to Iran has included missiles and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles — some of which have been deployed against Saudi Arabia by the Houthis in Yemen.

Chinese assistance has not adversely affected developments on the ground, and China also appears to be priced in by both the Saudis and Iranians. Chinese sales of weapons to Iran and Arab Gulf states may have been factored in by the opposing sides as the price of doing business with Beijing. While China’s current support for the Saudi missile program might dissatisfy some in Iran, Saudi Arabia is also not satisfied with the signing of the 25-year cooperation agreement between China and Iran in March 2021.

While both Saudi Arabia and Iran broadly accept China’s engagement with the other side, there may be limits. Both sides seem to accept that China will cooperate militarily with their rivals, so long as that engagement does not extend to anything more formal, like a defensive entente.

Yet Saudi Arabia has an advantage that Iran does not. If threatened, Riyadh can reboot its fading alliance with the United States. Iran’s situation is more precarious. Tehran lacks a similarly powerful global patron and so is more exposed to US threats and pressure. Iran’s leaders have looked to both Russia and China for diplomatic and military support in recent years but it cannot rely on them to the same extent the Saudis can rely on the United States.

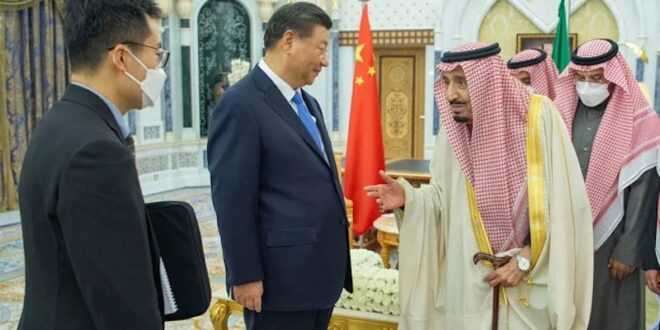

China has so far refused to adopt a more involved posture as a regional security provider or guarantor that could replace the United States. It is unlikely to do so at the anticipated China-Arab summit scheduled to take place when China’s President Xi Jinping visits Saudi Arabia next week. There, the focus will largely be on boosting trade ties and reaching agreements on energy and investments. Meanwhile, Moscow’s military status and prestige have been undermined by its war of attrition in Ukraine. Iran and Russia are also competitors in Syria, where they seek to maximise influence with the Syrian regime and as producers in the global energy market.

China has sought to maintain diplomatic balance in its relationships in the Middle East, especially in the Gulf between Saudi Arabia and Iran. This position has been understood and accepted by all sides in the region.

If regional or wider global dynamics change the relative positions of Saudi Arabia and Iran, there may be consequences for their rivalry. Should that happen, it would be despite Chinese activities in the region — not because of them. Beijing would then need to recalibrate its position accordingly. This could lead to shifts in China’s relationships with either side but for now, that seems more a question of if rather than when.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News