The recent emergence of OpenAI’s ChatGPT (part of the Generative Pre-trained Transformer family of language models) has attracted a lot of attention throughout the world. It is a chatbot released in November 2022, and, according to OpenAI’s website, its “dialogue format makes it possible for ChatGPT to answer followup questions, admit its mistakes, challenge incorrect premises, and reject inappropriate requests.” The model also involves a number of serious limitations, however, which are also mentioned on OpenAI’s homepage.

Though language models like ChatGPT are still in the infancy stage of development, their emergence has nevertheless generated a range of advanced discussions and debates among researchers involved in the field of language acquisition. On one side of the debate, for example, are world-renowned linguist Noam Chomsky, linguistics professor Ian Roberts, and AI researcher Jeffrey Watumull, who, in an essay published in The New York Times in March 2023, argue against the notion that artificial intelligence programs like ChatGPT would be capable of replicating human thinking and reasoning, in major part because “these programs cannot explain the rules of English syntax,” which renders their predictions always “superficial and dubious.”

And on the other side of the debate are those, like neuropsychologist Steven T. Piantadosi and linguistics professor Daniel Everett, who have not only suggested that language models can acquire the necessary structures of language, but also used the release of ChatGPT as a platform from which to launch a direct attack on Chomsky’s “universal grammar” theory, despite the fact that it has been supported, time and again, by studies in the field of language acquisition.

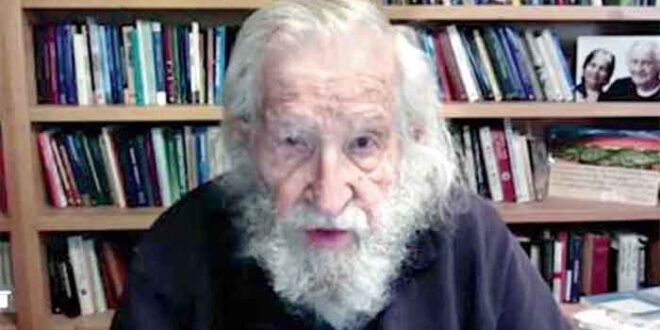

Put differently, the Chomskyan notion that humans are genetically encoded with a universal grammar, a sort of structural framework in the brain that makes possible the human capacity for language, is still considered by many in the field of linguistics as the most plausible explanation for language acquisition. So, let us discuss these issues, and more, in the interview that follows, with a scientist who is recognized in scientific circles around the world as the founder of modern linguistics, Professor Noam Chomsky. The interview was conducted via email. —Ramin MirfakhraieNoam, thank you for accepting my invitation for this interview. As you are well aware, the recent emergence of chatbots like OpenAI’s ChatGPT has created a global uproar, about which you, Ian Roberts, and Jeffery Watumull recently wrote an essay that was published in The New York Times titled “The False Promise of ChatGPT.”

Shortly after the publication of this essay, however, a number of your critics used the opportunity to challenge your theory of language acquisition, which was originally formulated in your pioneering book called Syntactic Structures (1957). Did this reaction surprise you in any way?

Noam Chomsky: I’ve seen a few pieces claiming that LLMs challenge the rich and extensive work of recent years on language acquisition, described falsely as “Chomsky’s theory,” I suppose out of unfamiliarity with the field. I haven’t seen anything that poses even a remote challenge from LLMs to my work, or any of the important work on language acquisition that I know of.

Unfamiliarity with the field might explain the flawed nature of non-expert criticisms of your extensive work on language acquisition, but what about expert criticisms of your research and theory, such as those put forward by neuropsychologist Steven Piantadosi and linguist Daniel Everett?

In a piece titled “Modern language models refute Chomsky’s approach to language,” for example, Piantadosi claims that “Modern machine learning has subverted and bypassed the entire theoretical framework of Chomsky’s approach, including its core claims to particular insights, principles, structures, and processes.” He further states that “the development of large language models like GPT-3 has challenged some of Chomsky’s main claims about linguistics and the nature of language” on three grounds:

First, the fact that language models can be trained on large amounts of text data and can generate human-like language without any explicit instruction on grammar or syntax suggests that language may not be as biologically determined as Chomsky has claimed. Instead, it suggests that language may be learned and developed through exposure to language and interactions with others. Second, the success of large language models in performing various language tasks such as translation, summarization, and question answering, has challenged Chomsky’s idea that language is based on a set of innate rules. Instead, it suggests that language is a learned and adaptive system that can be modeled and improved through machine learning algorithms. Finally, the ability of language models to generate coherent and coherent [sic] language on a wide range of topics, despite never having seen these topics before, suggests that language may not be as rule-based as Chomsky has claimed. Instead, it may be more probabilistic and context-dependent, relying on patterns and associations learned from the text data it was trained on. —Steven PiantadosiAnd in a similar vein, in an interview headlined “Exclusive: Linguist says ChatGPT has invalidated Chomsky’s ‘innate principles of language’,” Everett claims that ChatGPT “has falsified in the starkest terms Chomsky’s claim that innate principles of language are necessary to learn a language. ChatGPT has shown that, without any hard-wired principles of grammar or language, this program, coupled with massive data (Large Language Models), can learn a language.”

Are these claims valid in your view?

NC: Neither of them indicates any familiarity with the field of language acquisition. Even the most superficial familiarity reveals that very young children already have rich command of basic principles of their language, far beyond what they exhibit in performance. The work of Lila Gleitman, Stephen Crain, Kenneth Wexler, and many others makes that very clear. Many details have been discovered about the specific ways in which acquisition proceeds in later years as well. Charles Yang’s careful statistical studies of the material available to young children show that evidence is very sparse, particularly once the effects of Zipf’s law on rank-frequency distribution is considered.

It is absurd beyond discussion to believe that any light can be shed on these processes by LLMs, which scan astronomical amounts of data to find statistical regularities that allow fair prediction of the next likely word in a sequence based on the enormous corpus they analyze.

The absurdity is in fact a minor problem. More fundamentally, it is obvious that these systems, whatever their interest, are incapable in principle of shedding light on language acquisition by humans. The reason is that they do just as well with impossible languages that humans cannot acquire in the manner of children (if at all).

It is as if a physicist were to propose a “theory” saying “here are a lot of things that happen and a lot that can’t happen and I can make no distinction among them.”

Piantadosi is familiar with LLMs, but like many others, shows no awareness of these fundamental problems. Everett simply makes unsubstantiated claims that merit no attention.

The very fact that they attribute the theories to me reveals lack of familiarity with the rich and well-developed field of language acquisition.

Perhaps these critics’ lack of familiarity with the field of language acquisition stems from a more fundamental problem; namely, a potentially distorted view of your theory of language acquisition, which has had a lot of influence, to say the least, on much of what has taken place in the field in terms of theorizing.

Then again, this might be related to an issue that Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker raised in 2016. In an interview with John Horgan, published by Scientific American Blogs under the headline “Is Chomsky’s Theory of Language Wrong? Pinker Weighs in on Debate,” he talks about the unclear nature of “Chomsky’s theory of language” and how your concept of “Universal Grammar” is ambiguous in terms of what it consists of.

It thus would be tremendously helpful, I believe, if you could at this point briefly discuss your theory of language acquisition, especially, since it has gone through multiple revisions since its original formulation.

NC: It’s easy to discover what “Chomsky’s theory of language” refers to: there is publication after publication providing details. There seems to be a strange conception that there should be a fixed and unchanging theory of the nature of language. There isn’t, any more than in the sciences generally.

On language acquisition—or any process of growth and development—three factors are involved: (1) innate structure, (2) external stimuli, (3) laws of nature.

Any sensible approach to language acquisition will seek to determine how they interact to yield the transition from the initial state (1) to the relatively stable state attained. There has been considerable progress in all three areas. The Principles and Parameters framework provided the first real hope for a feasible account of the transition that would account for the diversity of possible human languages. That inspired a great deal of work aimed at determining how an infant can feasibly search through the parameter space to yield a particular language (or languages). Among major contributions, Ian Roberts’s recent work shows how very simple cognitive processes can achieve highly significant results, tested with thousands of typologically different languages. Experimental work has shown that very young children have mastered fundamentals of language, far beyond what they exhibit in performance, and careful statistical studies reveal that the data available to them is sparse and in crucial cases non-existent.

My own work has concentrated on (1) and (3), with principles of computational efficiency taken to be laws of nature—natural for a computational system like language. I can’t review the course of this work here: there is ample material in print, to the present.

To clarify a terminological point, often misunderstood, the technical term UG (“universal grammar”) refers to the theory of (1), the theory of the human faculty of language, apparently shared through the species, and with basic properties not found in other organisms, hence a true species property.

Going back to LLMs, with the approach that you have described above in mind, can we say that such models will someday be able to replace linguistics for understanding the human faculty of language?

NC: Their basic design ensures that this is impossible, for the two reasons I mentioned: the minor flaw, which renders the proposal absurd; the major flaw, which renders it impossible in principle.

Finally, do you think there should be any sort of government regulation of language models like ChatGPT, in terms of, say, privacy matters or data security, similar to what recently happened in Italy?

NC: As you know, there’s a petition circulating calling for a moratorium on development of these systems, signed by a wide variety of prominent practitioners. And there have been calls for government regulation. The threats are real enough. I frankly doubt that there’s any practical way to contain them. The most effective means that I can think of is the only way to counter the spread of malicious doctrines and ideology: education in critical thinking, organization to encourage deliberation and modes of intellectual self-defense.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News