Elections aren’t until Oct. 20, but disinformation campaigns are in full swing.

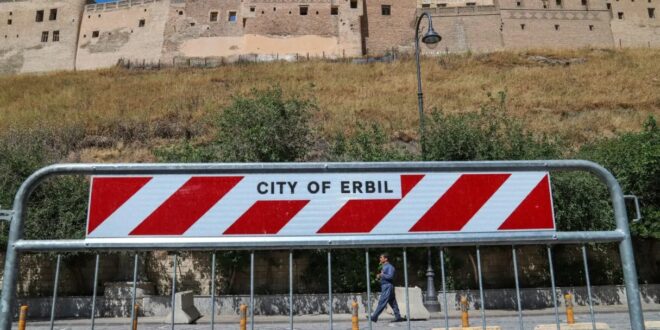

Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdistan Region will hold elections on Oct. 20. Although the formal campaign has not yet begun, the so-called “shadow media” is already in full swing spreading disinformation, promoting political spin, and attacking rivals.

One post claims the US and Iran are conspiring to remove Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) Prime Minister Masrour Barzani from power. Another post insists that an opposition figure asked a military commander to have soldiers shoot up his house in a contrived bid for sympathy.

One post from a supportive page hailed KRG Deputy Prime Minister Qubad Talabani as a “symphony of tranquility in the noisy forum of politics.” In contrast, an attack page claimed he was scheming to “humiliate” a faction within his own party and blame them in the event of an election loss.

The shadow media refers to networks of social media pages that are affiliated with political parties and powerful individuals. They mimic the appearance of legitimate — if low-quality — Kurdish news outlets by mixing in authentic news coverage and posting graphics in a similar style. Nevertheless, experts say their primary purpose is to manipulate public opinion in service of their patron.

“The influence of shadow media on the Kurdistan Region’s information landscape is profound,” explained Dr. Harem Karem at Pasewan Organization for Public Policy. “These outlets sow discord within society, erode the already fragile trust in public institutions, and severely damage the credibility of the journalism profession.”

Stoking Anger and Discord

The most popular pages, including most of those cited above, have more than 100,000 followers on Facebook, the most active social network in the Kurdistan Region. Even small operations pass through the feeds of tens of thousands of people every day.

Disinformation and malignant social media campaigns are not unique to the Kurdistan Region; they are a worldwide phenomenon. Yet, it has a profound and outsized effect on the Kurdistan Region’s relatively small political community, which has fewer than three million eligible voters.

The rise of the shadow media was not an organic process. It was designed, directed, and funded by some of the most powerful politicians, businesspeople, and security forces in the Kurdistan Region, who frequently hide their involvement through proxies and shell companies in order to maintain a façade of independence.

All parties across the political spectrum are involved, including the two ruling parties and the steadily expanding galaxy of opposition groups.

For the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which have controlled the Kurdistan Region for the last three decades, the pages are a way to frame their most prominent families as paternal protectors and statesmen. They are also a way to launch defamatory attacks on rivals, journalists, and critics.

For opposition parties, shadow operations are a relatively cheap way to bypass mainstream outlets, stoke public anger, and introduce doubts about the ruling parties and competitors within the opposition.

“Criticize the Authorities”

According to one employee, who works for a page associated with an opposition party and spoke on condition of anonymity to protect their job, shadow media operations are staffed by small teams. They receive direction from an editor and must write and edit numerous posts each day to keep a steady stream of content flowing.

The employee said they were paid 900,000 Iraqi dinars (around $600 at current market rates) per month for their work, which makes for an above average paycheck in difficult economic conditions.

“We are opposition media and our direction at work is to criticize the authorities,” they said. “We have tried not to become a party media despite being financially supported by an opposition force, but sometimes we need to convey our articles to viewers and readers according to the policy of [that party].”

While some patrons try to keep as much distance from the shadow media pages that they fund, others prefer a more hands-on approach.

Hevar Jalal used to work for the New Generation Movement, an opposition party led by businessman Shaswar Abdulwahid, as the head of its official media shop. During the course of his work, Jalal became increasingly aware of the party’s concealed media operations, which had “dozens of large shadow pages to be used against the president’s rivals.”

In an interview, Jalal claimed that Abdulwahid closely monitored social media to see what was being said online and would tweak the language of posts before sponsoring them on Facebook.

“He changed his opinion about parties and personalities every day, sometimes sending messages that everyone should write against someone or support someone else,” Jalal said, adding that he eventually resigned from his position with the party after becoming disillusioned.

No Clear Distinction

These cases show that the line between legitimate journalism and political activism, on the one hand, and disinformation and clandestine political attacks, on the other, is not at all clear in the Kurdistan Region’s highly politicized information space.

“The distinction between the mainstream and shadow media has become increasingly difficult to discern, as they often overlap or influence one another,” Karem noted. “The current state of the information ecosystem is chaotic, with no immediate efforts underway to restore order.”

“Unrealistic and Dishonest”

Beyond sowing confusion and disinformation, the shadow media frequently attacks prominent women, government critics, journalists, and minority communities.

Rezan Sheikh Dler, a lawyer and women’s rights activist who served two terms as PUK MP in the Iraqi parliament, said that “it cannot be imagined how many big attacks have been done by these shadow media pages on me. They are so unrealistic and dishonest.”

Dler said that pages would sometimes publish fake statements in her name in order to provoke public outrage. She added that it is normal for public figures to be talked about, but that the shadow media’s extreme actions resulted in real harm.

When women working in the political field face such instances, she said, they become frightened, “and that fear is worse than hopelessness.” She added that women often face threats of fake photos or videos that show them in compromising situations. “This makes women politicians unable to speak the truth and to withdraw from politics.”

It is clear that the region’s shadow media, a pervasive presence in the information landscape, in has a malignant impact both in broad societal terms and for specific individuals and communities. Yet, it is difficult to address these harms and reduce the sector’s impact.

“I would often decide to go and file a legal complaint,” Dler said. “But then I thought that with all these shadow media pages, how can you file a complaint against so many people and parties?”

She believes that since the parties “created the shadow media, they can remove them as well.”

“Difficult to See the Truth”

For his part, Karem believes in a more comprehensive approach, including improving media literacy and ensuring that major social media companies conduct better oversight of the content on their platforms. He also urged the Kurdistan Parliament to pass legislation to update media regulations, ensure transparency in media funding, and improve access to information.

However, these solutions cannot be implemented in time for the parliamentary elections, now less than two months away. As the campaign heats up, the pace and intensity of shadow media’s activities will only grow.

“Only the creator of the storm can understand what is going on,” Jalal said. “The shadow media has confused the Kurdish media in such a way that it is difficult to see the truth.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News