The spotlight and many analyses are on the future of Syria and its ruling system after the change of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Many questions are raised about the country’s political and social future, the future shape of Syria and its ruling system, and how politics can be recycled away from internal competition for power and external interventions. Despite the regional and international consensus on the need to establish stability in Syria, the risks associated with the transitional path may result in several repercussions, especially with regard to the tactical agreements between the Syrian armed and political forces.

Syria is entering a transitional phase amidst uncertainty, after the armed opposition took control of the capital Damascus on December 8, 2024, and changed the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, in an accelerating scene since the “Syrian armed opposition factions” began an operation called “Deterrence of Aggression” on November 27, led by the “Al-Fath Al-Mubin” operations room based in Idlib, during which they took control of Syria’s main cities one after the other and along the M5 international highway. “Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham” announced a transitional period led by a caretaker government headed by the former regime’s Prime Minister, Muhammad Ghazi al-Jalali, to run Syrian administrations and institutions, to close the country after six decades of Baath Party control, a quarter century of Bashar al-Assad’s rule, and more than ten years of the crisis that has been raging in the country since 2011.

In fact, these developments raise several questions about the country’s political and social future, and about the future form of Syria and its system of government, in light of the multiplicity of local Syrian actors and the wide differences between their orientations and backgrounds, the demands of Syrian citizens at home and abroad, and how politics can be recycled away from internal competition for power and foreign interventions.

Future requirements in the coming Syria

The spotlight and many analyses are on the future of Syria and its ruling system after the change of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, in a relatively peaceful transition of power, compared to the intensity of internal fighting and the multiplicity of actors in the Syrian crisis scene since 2011. On the one hand, the country has maintained the continuity of its institutions, and on the other hand, the events have excluded two of the most important players in the country, namely Russia and Iran, and behind them a group of armed factions and militias, most notably the Lebanese Hezbollah. The news of the change of regime came to theoretically meet the aspirations of the Syrian people, who were ruled by a regime classified as “extremely authoritarian”, accused of marginalizing the majority of the people, and looking with hostility towards Islamic and liberal ideologies and not taking into account the rights of non-Arab minorities, such as banning the Kurdish language from circulation and printing in 2019, consolidating a previous decision to ban its use in state departments in 1986.

However, the future of Syria is not limited to local political affairs only, and cannot be confined to the scenes following the fall of the regime and the initial agreement between the societal components to achieve that goal, as much as the success of the day after Bashar is linked to a set of requirements and considerations that must be taken into account in light of the transitional phase and what it establishes later, and the most important of those considerations are:

First: International Consensus

All countries in the region and the world sought to convey the idea that the “deterrence of aggression” operation came to represent a local and internal affair, and that many countries, with the exception of Turkey and the United States, were content to watch the transformations in the country. However, after the scene became clear and “Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham” took control of Damascus, countries increased their direct and indirect involvement in the Syrian affair, and began formulating their demands and requirements from the country’s interim administration, and assessing the future of their relations with it, as is evident in the UN and European diplomatic visits to Damascus, and the security meetings in the Jordanian city of Aqaba, which all agreed to support a comprehensive political process. Therefore, the future of Syria cannot be separated without looking at international considerations, specifically in three main approaches as follows: 1) The foreign military presence on Syrian soil, 2) The need for international consensus for reconstruction, 3) The need to get rid of international sanctions on the former regime and the transitional government.

In terms of military presence, Turkish and American forces are deployed heavily in vital and strategic areas of the country, where American forces and Kurdish protection forces control about a third of the country’s area in the northeast, and are deployed in the area extending from the northeast of the country at the Euphrates River to the southeast at the Tanf border crossing, where the American military base is located, guaranteeing the security of the border triangle between Syria, Jordan and Iraq. This area includes most of the oil, agricultural and water resources, while the Turkish army is deployed in the provinces of Idlib, Aleppo, Raqqa and Hasakah, and provided logistical and armament support to the “Military Operations Management” and “Dawn of Freedom” rooms in the fight against the regime in the past, and against the Syrian Democratic Forces currently. Meanwhile, Russia maintains two naval bases on the Syrian coast, namely (Tartus and Hmeimim). Thus; The deployment of foreign forces on Syrian soil keeps their countries active in the political scene, especially since the three countries (the United States, Turkey and Russia) support three components of Syrian society, as American forces provide support to the Kurds, while Turkish forces support Sunni Islamists, and Russian forces are present in an environment of the Alawite majority. It is likely that these three forces will compete, contrary to the representation of their supporters in the upcoming political and military authority, or the threat and demand for self-administration similar to the Kurds of Iraq for Washington, or Haftar’s forces in Libya for Russia.

As for the need for the international community in reconstruction management operations, the cost of which is estimated at $200-300 billion, distributed across various cities and governorates in Syria, for example, the number of destroyed buildings in Aleppo is estimated at 36,000, in Eastern Ghouta at 35,000, in Homs at 13,000, in Raqqa at 12,000, and in Hama at 64,000. In reality, it is unlikely that Syria will be able to carry out reconstruction operations alone and without extensive international and Arab assistance, which places the future of the political process in the midst of a wide range of international Arab, European, or American requirements for participation in financing reconstruction, which strengthens some files at the expense of others according to the requirements of the donor party, which exposes the entire process to the risks of intersecting or clashing interests. For example, countries such as Germany, France, and Sweden focus on supporting minorities, primarily the Kurds, while countries such as Turkey and Russia oppose granting the Kurds more political or geographical advantages. The influence of these countries extends to files other than reconstruction, specifically in the sanctions imposed on the former regime or on Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and its leader Ahmed al-Sharaa (Abu Muhammad al-Julani), including the Caesar Act to Protect Syrian Civilians in the United States in 2019, the first and second Captagon Acts in 2022, as well as the US State Department’s classification of the leader of the “Military Operations Department” Ahmed al-Sharaa as a terrorist since May 2013, and the allocation of a $10 million reward for anyone who provides information that helps in arresting him since 2017. The decision to remove al-Sharaa and the organization from the terrorist lists remains an effective weapon in Washington’s hands to put its requirements on the agenda of the “Military Operations Department” in the future.

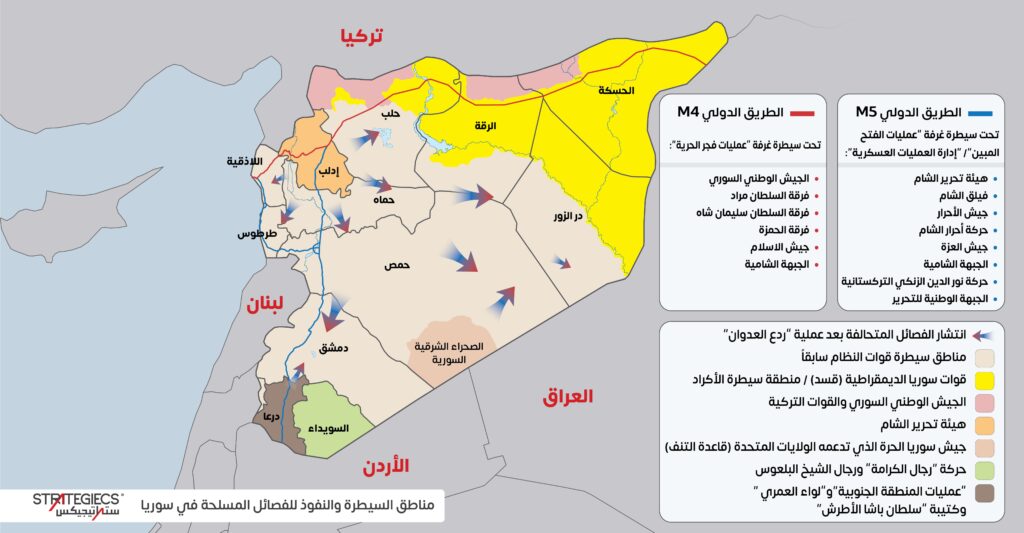

Second: Restricting weapons to the state

The most prominent requirements of the transitional phase and the most important features of its success are represented in restricting weapons to the hands of the legitimate and regular authorities, as manifestations of armament are widespread in the country, and the manifestations of this spread vary according to the party carrying it, the areas of deployment, and the purposes of its use. On the one hand: the “Al-Fath Al-Mubin Operations Room” or what has become known as the “Military Operations Department” after the change of the regime, controls most of the main Syrian cities, along the international highway M5, while the “Fajr Al-Hurriya” Operations Room is deployed along the international highway M4 in parallel with the deployment of the Kurdish Protection Units and the intersection of its areas with the “Fajr Al-Hurriya” Room. However, both rooms (the Military Operations Department and Fajr Al-Hurriya) include a wide range of armed factions and battalions. In the first, “Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham”, formerly Jabhat Al-Nusra, is the largest of these factions in partnership with “Faylaq Al-Sham”, “Jaysh Al-Ahrar”, “Harat Ahrar Al-Sham”, “Jaysh Al-Izza”, “Al-Jabha Al-Shamiya”, the Turkestan Nour Al-Din Al-Zenki Movement, and the factions of the “National Liberation Front”. As for the second; It represents an alliance of a group of factions that were united by Turkey in 2017, and includes the “Syrian National Army”, which is made up of a group of factions that previously formed the Free Syrian Army, the “Sultan Murad Division”, the “Sultan Suleiman Shah Division”, the “Hamza Division”, the “Army of Islam” and the factions of the “Al-Sham Front”.

On the other hand, the country faces a vertical spread of weapons between ethnic minorities on the one hand, and ideological factions on the other. For example, the Kurds have the Kurdish Protection Forces, while the areas where the Druze community is spread in Sweida have witnessed the establishment of several factions, including the “Men of Dignity” movement and the “Men of Sheikh Wahid al-Balaous,” whose mission is to protect members of the community from the regime forces and defend demonstrators. On the third hand , Weapons are spread horizontally across the geography of Syria. While most of the opposition factions are spread across the country, they are divided according to their origins and areas of influence geographically. In the north, there is Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, the Syrian National Army, and factions such as Jaysh al-Islam and others, a large portion of whom are from the region (including Aleppo, Hama, and Idlib). In the south, there is the “Southern Region Operations” faction, the “Al-Omari Brigade,” and the “Sultan Pasha al-Atrash” battalion, all of which were formed by officers who defected from the regular Syrian army. In the west, there is the Free Syrian Army, which is supported by the United States and is active in the Syrian desert on the Iraqi-Syrian border, and in the east, there are the Kurdish Protection Forces.

Therefore, the requirement to limit the presence of weapons to the state only is considered a basic priority for the next stage in light of the multiplicity of Syrian armed organizations and factions and the state of chaos and political vacuum that followed the collapse of the regime. This basically requires handing over weapons to the army institution or to a military council after its formation, with the integration of some fighters from the factions and organizations into the national army after their rehabilitation, as one of the factors for maintaining the stability process in the preparation process is to maintain the structural structure of the army even if its leadership is changed, while strengthening the capacity of the state’s security services to ensure security. In fact, this is considered one of the most complex requirements, especially with the diversity and multiplicity of armed factions and the difference in their goals and objectives, in a way that threatens the possibility of their separation or fighting in search of broader gains. These factions have previously clashed in armed conflicts, including Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham against other factions affiliated with the Free Army in 2017.

Third: Centralization of power

Before the “Deterrence of Aggression” operation, Syria was divided between three authorities: the regime and the government in Damascus, the “Salvation Government” in the areas controlled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham in Idlib, and the autonomous administration led by the Syrian Democratic Council in the northeast of the country. After the collapse of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, the head of the “Salvation Government”, Mohammed al-Bashir, became the head of a transitional government until early March, which means that the country now includes two authorities. The first – the interim government – controls most of the Syrian geography, while the second maintains its areas of administration in Hasakah, Raqqa and the surroundings of Deir ez-Zor, after it withdrew from Aleppo following the “Dawn of Freedom” operation launched by the opposition Syrian National Army. On the other hand, the centralization of political power is not official or structural throughout the country, as many minority areas are subject to local authorities led by sheikhs and tribal leaders. One of the most prominent examples of this is the Druze situation in the Sweida Governorate, which remained a scene of demonstrations against the former regime, driven by the notables and leaders of the Druze community. This situation may be a future model for the Syrian coastal areas that include a large Alawite presence. Although the “Deterrence of Aggression” factions entered the Syrian coastal areas, and the sect’s sheikhs disavowed Assad, signs of instability are still evident, including that most of the leaders of the military establishment and militias headed to the coast after the regime change, and there are latent fears among the Alawites about their presence, especially due to the former regime’s association with them. Thus, these issues make the future of Syria dependent on the extent of the transitional authority’s ability to unify the country under one central leadership, which requires monitoring the diversity of the forces regulating the transitional phase, and how to involve all national components and different segments of society at home and abroad in the political process. Otherwise, the more Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham seeks to monopolize decision-making and representation for a sect, ideology, or region, the higher the risk of conflicts and the transition to a federal state, division, or chaos scenario.

Fourth: Transitional Administration

Syria today faces a complex scene in many aspects. On the political side, the country suffers from a political vacuum with the absence of central authority and leadership, which is a central challenge after the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, linked to fears of the country entering a state of chaos if the post-regime phase is not managed in an organized and consensual manner and according to a comprehensive and inclusive transitional mechanism, and a unified national vision that guarantees the preservation of state institutions and the continuation of their operation and the implementation of their service tasks without collapsing, especially in light of the structural dependence of these institutions on the previously ruling Baath Party. With the fall of the regime and the repercussions of the absence of political stability, fears arise about the possibility of conflicts over power and rule between the opposition political and military forces, especially with the existence of previous experiences in which the collapse of government led to internal conflicts after the collapse of state governmental institutions, and the disintegration of key institutions such as the army and security services, which resulted in chaos and the absence of law, most notably the Iraqi scene after 2003, and the Libyan situation after the events of the Arab Spring.

Therefore, the next stage requires a national Syrian consensus within a unified vision to manage the stage in a consensual manner until new changes are made, in a way that enables the state to establish a government or council and transitional institutions capable of maintaining security and stability, in order to prepare the country for a democratic political transition; as failure to manage the transitional stage may lead to long-term chaos, especially if the roots of the Syrian crisis are not addressed and justice for all is not achieved, which requires the factions and organizations to be able to reach political consensus around a unified vision to manage the transitional stage with stability, especially with the differences in their ideological orientations and regional interests.

On the other hand, the transitional phase of the political system needs internal and external support (international and regional), so that the active entities in the scene are able to form a transitional council that includes representatives of all its parties, taking into account diversity and without the dominance of an ethnic or religious component to achieve national and representative consensus. However, this requires them to realize their need to build a central authority without the interference of the supporting parties in internal affairs to serve their strategic interests that are inconsistent with respecting Syrian sovereignty over the country. This requires the formation of representative bodies for them, which include various entities with their political and social diversity and enjoy international and popular support, while ensuring the independence of these bodies from external interference or attempts at partisan control so that they are responsible for leading the stage to achieve stability, drafting a new constitution, and preparing for elections in a free and democratic manner.

The transitional bodies are also essential organizational tools for the transitional phase, including the formation of a transitional government with clear powers and fair representation that brings together the various Syrian components, and in a way that prevents the phase from slipping into new local conflicts, then drafting a new constitution based on national consensus on its foundations, and that meets the aspirations of the Syrian people and is consistent with the changes the phase requires in the form of the political system in a way that reflects the democracy it requires, taking into account that the weakness of the structure of the transitional bodies and institutions hinders their path and limits their ability to manage state institutions and supervise their services, leading to impeding progress in achieving a successful political transition process, as happened in the Libyan experience, in which the absence of these bodies and their roles led to the production of a state of chaos, while Tunisia, for example, was able to establish bodies that were able to manage the presidential elections.

Fifth: Achieving social integration

The next stage requires achieving social integration that enhances national unity and restores the social fabric that was disintegrated during the years of the Syrian crisis, to ensure the stability of the country, especially in light of the diversity of cultures and identities resulting from internal displacement and asylum in various countries, which created a state of cultural and social disparity among Syrians; as millions of them were exposed to different living and cultural conditions, whether inside the country or abroad, and the geographical distribution of Syrians in host countries with diverse cultures and social systems led to the creation of differences in customs, traditions, political, social and economic visions.

On the one hand , the crisis in 2011 created a new social dimension, represented by the heterogeneous cultural pluralism of the Syrian people, which is a cross-border pluralism and not a popular cultural diversity. The residents of northeastern Syria, including the displaced, dealt with a culture closer to Turkish. The Turkish lira was the currency in circulation in the market, and Turkish relief agencies supervised the distribution of humanitarian aid. The Turkish education and language systems also overlapped with the residents and inhabitants of those areas. On the other hand, many refugees live in difficult conditions in refugee camps inside and outside the country, and a new generation of Syrians has grown up who do not have civilized experiences or knowledge of living in cities, and have limited resources and skills that could qualify them in the future for the labor market or contribute to reconstruction. On the other hand, A group of Syrians have acquired qualitative skills and a liberal Western culture, especially refugees in advanced industrial countries (Europe, the United States, Canada, Japan, etc.). These people will certainly have qualitative contributions to the future of Syria and reconstruction, but their return is conditional on a cultural and financial level parallel to their current locations, especially since some of them hold positions in international organizations and institutions or work with Western governments, and some have a network of international economic relations that can be used in the future reconstruction of Syria. Consequently, these people may have the ability to present reconstruction plans, build institutions (institutional reform), and manage the state through international institutions if they obtain local popular and political support.

On the other hand , the return of refugees to their homeland is a basic condition for the comprehensive and sustainable reconstruction of Syria, but this requires a stable and safe environment; as the return of refugees is linked to all the aforementioned requirements, and the return of about ten million refugees must be a basic priority in the next stage, which requires reconstruction and the provision of appropriate living, security, economic and service conditions, while providing them with security and legal guarantees; based on the importance of the participation of refugees and expatriates in establishing the social and economic future of the state and rebuilding its social fabric, as they represent an important economic and human force for reconstruction, improving living conditions, developing investments and achieving development. There are refugees in the Arab country with low incomes whose return requires employment programs, rebuilding infrastructure in destroyed areas, and providing economic assistance, which requires international consensus to support them through civil society organizations, revitalizing the economic situation and encouraging investment through reconstruction programs to enhance opportunities for unity and solidarity among different segments of society.

Scenarios of the ruling system in Syria

The future in Syria seems open to several scenarios, all of which are linked to a set of challenges, actors, and requirements, the interaction of which forms the result of the model and form of the future political system in the country, which can be summarized as follows:

Scenario 1 : Taliban rule model in Afghanistan

This scenario assumes that Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, which was founded on the “Salafi-Jihadist” approach when it was called “Jabhat al-Nusra”, will follow the path of governance followed in Afghanistan, where the contexts of control and the features of thought are similar in both cases. On the one hand, the Taliban movement made sudden and rapid advances in 2021 throughout the country and was able to reach Kabul and seize power within a month, then declare an Islamic state led by the movement. This path came with reconciliation and agreement with the United States, which withdrew its forces at the same time as the movement’s fighters arrived in the capital. As for Syria; The US-Turkish understandings with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham seem clear, as Washington preferred to hold the former regime responsible for the “deterrence of aggression” operation, and warned Iraq and Iran against interfering in Syrian affairs, while Turkish support for the organization and its leadership is clear, as Ankara prefers to work with an Islamic government that is a partner in its neighborhood, and follows its positions, especially on issues of its national security such as the Kurdish issue. It was noteworthy that Qatar entered the line of developments after the visit of the head of the Qatari State Security Service, Khalfan al-Kaabi, to Damascus on December 15, coinciding with the presence of the head of the Turkish Intelligence Service, Ibrahim Kalin, there, and hours after a visit by US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken to Ankara and Doha during his tour of the region that included Jordan. The two parties held meetings with the leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, Ahmed al-Sharaa, and the interim Prime Minister, Mohammed al-Bashir, to discuss the future of the country in the next stage. Thus, the visits from Turkey and Qatar become the first official international visits to Syria after the change of regime.

This scenario is reinforced as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham moves to shape the country’s future in a single and centralized manner, leading Sharia to become the country’s next president, and for Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham’s members to become the nucleus of the Syrian army in the future, establishing a ruling system based on Sharia as a legal reference and the control of forces with Islamic orientations, with the drafting of a constitution with Islamic values, focusing on implementing the values of justice and equality from an Islamic perspective. This requires Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham to impose its control over minority areas, especially Alawite areas and areas controlled by the Kurds.

Scenario Two : The Model of the Governance System in Iraq

This model assumes the formation of two governments in Syria, one the central government in Damascus, and the other the Kurdish self-administration government in the northeast, with the former responsible for defense, foreign policy and finance, and the latter responsible for administering the Kurdish-controlled areas of Syria, which, as in the case of Iraq, would include most of the country’s oil and gas resources. In light of this scenario, it is likely that the Kurds will retain their armed forces, similar to the Peshmerga, and that they will be integrated into the future Syrian army, as demanded by the commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces, Mazloum Abdi. This is reinforced by the American insistence on preventing the expansion of the “Dawn of Freedom” operations towards the areas controlled by the Kurds in Raqqa and Hasakah, where American forces are present. On December 11, 2024, the US Secretary of Defense announced working with the Kurdish forces to confront the factions supported by Turkey, but he faces a challenge in the opposition of Turkey, the main supporter of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and the fighting factions in the “Dawn of Freedom” operations room. It is likely that countries such as Iran and Iraq will view the risks of establishing Kurdish self-administration, but it has the approval of the United States, Israel, and perhaps Russia.

In this scenario, the future model of governance in Syria will be federal, achieving a balance between the Damascus government and the Kurdish region, and including local and federal elections. This form allows the division of the state into regions that enjoy a degree of self-rule through powers to manage their affairs, but while maintaining the authority of the central government to be responsible for sovereign issues. This ensures the participation of minorities in managing their geographical areas in a way that undermines internal conflicts between them, takes into account ethnic specificities, and at the same time preserves Syria’s geographical unity.

Scenario Three : The Security Confederation Model

This scenario assumes that the country’s governance model will move towards dividing it on geographic, security, sectarian and ethnic grounds, as there is still a state of uncertainty among minorities, including Alawites, Druze and Kurds, regarding the direction drawn by the Islamist forces controlling the scene, especially since each of these minorities has its own armed factions. In addition, Alawite officers and leaders in the former regime have launched a broad rebellion against the transitional authority, with the aim of obstructing its progress or increasing the security and political challenges facing it. For example, an ambush set up by gunmen loyal to the former regime led to the killing of 15 members of the Islamic “Faylaq al-Sham” faction in Latakia Governorate, the stronghold of the Alawites. This is considered the first counterattack by elements of the former regime since its collapse, and at the same time indicates intentions and plans to launch similar attacks in the future, which means that Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham faces serious challenges in implementing central rule throughout Syria, which, if it happens, will remain vulnerable to stressful and costly security shocks and incidents. What reinforces this scenario is that the geographical distribution of minorities is supported by external powers. While Turkey supports the transitional government led by Islamists, the United States supports the Kurdish self-administration in the northeast of the country, while Russia supports the Alawites and the remnants of the former regime, along with Iran, Hezbollah and Iraq. As for Israel, it seeks to open channels of communication with the Druze community in Syria. Israeli media outlets have reported on the demands of the notables of the Syrian town of Hadar from Israel, including the occupied Golan. According to Israeli army spokesman Avichay Adraee, the head of the Israeli Intelligence Agency, Shlomi Bender, met on December 11 with the leader of the Druze community, Sheikh Muwaffaq Tarif, at a time when the Israeli army was launching an air and naval campaign to destroy the heavy weapons that the Syrian army had, and amid an Israeli military incursion into the occupied Golan, during which it took control of Mount Hermon.

Scenario Four : The Model of the Democratic Civil State

This scenario assumes the success of the transitional authority in establishing a democratic civil governance model, through a comprehensive national army, strong institutions, and a representative electoral system, taking into account the negatives of the sectarian distribution of powers, such as in Iraq and Lebanon. Some statements issued by the leaders of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and the transitional government indicate a future vision for a civil form of the state and its system of government, based on the Syrian national identity away from the existing sectarian identities, and building the relationship between the state and the people on the basis of citizenship only, without discrimination on the basis of race, religion, sect, or denomination, where the political identity of the state is citizenship, and the source of legislation is positive laws, in the presence of a central administrative structure, with the separation of powers achieved, and the effectiveness of state institutions and their integration with civil society institutions that rely on efficiency to achieve development, social justice, and peaceful coexistence for all. On this basis, many countries have changed their positions towards the transitional authority despite the classification of its leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, on the US terrorism lists, as Washington has not ruled out removing this classification, and US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken has announced direct contacts with the body, while other European countries such as Germany and France are awaiting the transitional authority’s position on the rights and representation of minorities. In fact, the US pressure tools through the military presence in Syria and the economic sanctions on it, and then Syria’s need after the regime change for the flow of European and Arab investments and funds to rebuild and invest in the country, impose on the transitional authority to take into account the requirements of all of these countries when establishing a future governance model, especially since the return of refugees or not may remain another pressure card on the authority, in terms of preventing competencies from returning, or pushing them to return to increase the population and economic burdens on the new authority.

Finally , these scenarios present the future of the upcoming Syrian political system and its possible forms. However, these scenarios require a sustainable state of stability, the preservation of which is a complex issue and a major challenge for the transitional authority, as managing the upcoming scene is characterized by many sensitivities that may at any time lead the country to enter a state of chaos, a power vacuum, and geographical, ethnic, and sectarian division.

Despite the regional and international consensus on the need to establish stability in Syria, the risks associated with the transitional path may result in several repercussions and warnings, especially with regard to the tactical agreements between the Syrian armed and political forces, which have not yet risen to the level of strategic integration in vision, goal and entity. Thus, as stated in an article by the Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Strategies Institute, Hasan Ismaik, in 2018, any negotiated peace agreement would constitute a bandage, at least temporarily, on an unstable truce, and this is likely to remain so until the scars and perceived grievances begin to diminish. Therefore, the main obstacle to peace is knowing how to rebuild collective civil discourse.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News