Introduction

With the February 10 executive order renewing and enhancing US tariffs on steel and aluminum,1 President Donald Trump has given shape to his vision of the United States in the global economy. It is a vision of economic security based on walling off the United States from free flows of international trade and no longer providing economic largesse to others for the sake of systemic stability. He is not alone in his views; indeed, his return to the White House signaled that much of the US public is tired of the obligations of international leadership, both political and economic. Trump won the 2024 Presidential election largely because of fears about the US economy, and tariffs were a prominent part of his campaign. Although his voters may not have fully understood the implications of such measures, the Trump administration is now demonstrating that tariffs—or at least the threat of them—are central to the US approach to the global economy. This shift will have economic and political ramifications around the globe.

For Europe, and especially for the unique institution that is the European Union (EU), this marks the beginning of a new phase in the US-European relationship, one based on different assumptions than those that have guided the transatlantic partnership over the last eighty years. Europe can no longer assume the existence of a strategic partnership in which the United States serves as the protector. Nor can Europe be passive in this new world and simply wait for the old pre-Trump consensus on US trade and foreign policy to reemerge. European leaders have long given priority to ensuring that it supports Washington’s choices and vice versa. Even the structure of Europe today—with its two premier institutions, NATO and the EU—came out of a European design built with strong US support. But today, Europe faces its own challenges: a faltering economy, an aggressive neighbor and unsettled region, a “systemic rival” in China, and a range of internal political challenges, led by far-right extremism. For Europe to deal effectively with the new US reality, it must have its own consensus, reflecting its own interests and environment.

One thing is clear: the new US-EU relationship will be far more transactional. The second Trump administration will not judge European countries as loyal allies, but rather according to their strengths and weaknesses as rival negotiators and what they bring materially to the relationship with the United States. In response, the EU and its member states should not depend on the idea of a strategic partnership but rather seek to conclude a series of deals. While the EU may also seek to maintain and support the international legal order—including the World Trade Organization-based trading system—it should not look to the United States to participate in this endeavor. If anything, the US approach is likely to challenge European efforts to strengthen the international legal regime and multilateral governance. Nor should European leaders imagine that the second Trump administration is an aberration; Trump’s victory has emboldened the isolationist and nationalist tendencies in the United States, and they will be a key—if not dominant—force for some years to come. The EU should plan accordingly.

Trump and the European Union

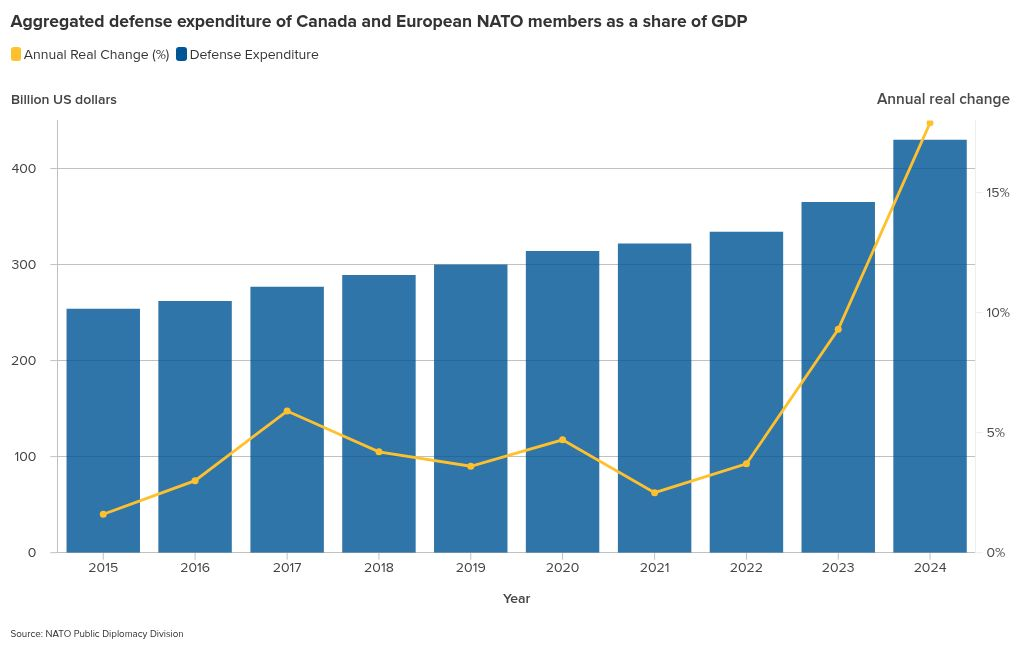

The possibility of a Trump presidency has caused much consternation in Europe, and deservedly so. The first Trump administration proved itself hostile to both NATO and the EU, and Trump himself has repeatedly criticized those institutions as well as many individual European governments, especially Germany. His second term may see less criticism of NATO since military spending by European governments has increased. Trump seems convinced that his earlier criticisms drove that increase and European leaders will not disagree, although an argument can certainly be made that Russian President Vladimir Putin was even more influential. But Trump may also calculate that even more pressure—including demanding military outlays at three, four, or even five percent of gross domestic product—could benefit his efforts to further reduce European reliance on the United States.

But whichever path he takes toward NATO, Trump is likely to continue his rants against the EU. Trump has long believed that the EU was set up to “take advantage” of the United States, especially through trade.2 He has focused on trade in goods, where the EU has a significant trade surplus with the United States, second only to the surplus held by China. But the EU’s $202 billion imbalance in goods trade in 2023 is significantly offset by the US surplus in trade in services, bringing the total to $125 billion.3 Throughout the campaign, Trump made his position very clear, saying he would impose a 10 percent tariff on goods from Europe: “The European Union sounds so nice, so lovely. All the nice European little countries that get together, right? They don’t take our cars. They don’t take our farm products. They sell millions and millions of cars in the United States. No, no, no, they are going to have to pay a big price.”4

But Trump’s concerns about the EU are about far more than trade. His antagonism is rooted in the view that the EU itself was created so that a group of smaller countries could take advantage of the United States. In this view, the EU has become a trading and regulatory power that is protectionist at its core, while refusing to take on the security and defense responsibilities that such a status should require. In his first term, Trump was an active supporter of Brexit, and he and other officials repeatedly asked other EU member states when they would be leaving the Union. He also floated the idea of a bilateral US-Germany trade deal before then-Chancellor Angela Merkel told him several times that this was impossible; that only the EU could negotiate on trade.5

Every indication is that these long-standing views will remain constant throughout the second Trump administration. Thus, European leaders should not only expect criticism about their defense and trade policies, but also an intentional effort to divide EU member states from each other and weaken the institution. Given Trump’s transactional approach to foreign policy—it is all about the deal—negotiating with a divided group of small countries would be preferable to dealing with one of the most powerful economic blocs in the world. Moreover, Trump does differentiate between European countries and leaders. He has praised Hungarian President Victor Orban as “a great man,”6 and Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni of Italy as a “fantastic woman,”7 but has been openly critical of Germany and its current Chancellor Olaf Scholz and his predecessor, Angela Merkel.

The EU response: A new transatlantic deal?

Thus, as the second Trump administration swings into action, Europe—and specifically the European Union—finds itself in a challenging situation. With war on its doorstep and its economy slumping, Europe must now also renegotiate its most important international partnership. Moreover, it must do so with a partner whose leader is unpredictable and clearly not committed to long-standing assumptions about the desirability of a strong transatlantic partnership. In fact, the first challenge for the EU will be to convince the Trump administration that engagement with the EU can be worthwhile.

For that reason, in the short term the EU must respond to a transactional US president and his threat to renew steel and aluminum tariffs with a good deal—but one that also incorporates Europe’s interests. While some observers argue that the EU should respond to tariffs with retaliation, tariffs would raise costs in Europe at a time of already high prices. But tariffs do provide leverage; indeed, Trump often characterizes potential US tariffs as bargaining tools and clearly used them to elicit some concessions from both Canada and Mexico before suspending those tariffs for a month. And the EU must soon decide whether and how it will use its own leverage. It is now finalizing a retaliation list in response to tariffs the United States levied on black olives in the first Trump administration. And it must decide by March 31 whether to continue the suspension of retaliatory tariffs established in response to initial US tariffs on steel and aluminum.

The Trump administration, in announcing renewed steel and aluminum tariffs, cancelled the Biden administration’s arrangement with the EU to admit those goods under a tariff-rate-quota (TRQ). But it has also held off imposing those tariffs until March 12, leaving a window for negotiation. The EU should take full advantage of that window, resisting the temptation to retaliate immediately and instead focusing on developing a deal that could stave off US tariffs while also serving EU interests. It may be that the threat of retaliation will be required to get the United States to negotiate, as during Canada’s and Mexico’s recent experiences with the Trump administration. Even then, the question is whether EU threats of retaliatory tariffs will bring Trump to the negotiating table or reinforce his antagonism toward the EU. The answer is likely to depend on what else he believes could be gained by negotiating. Thus, any retaliatory tariffs—to be useful—should be part of a larger deal.

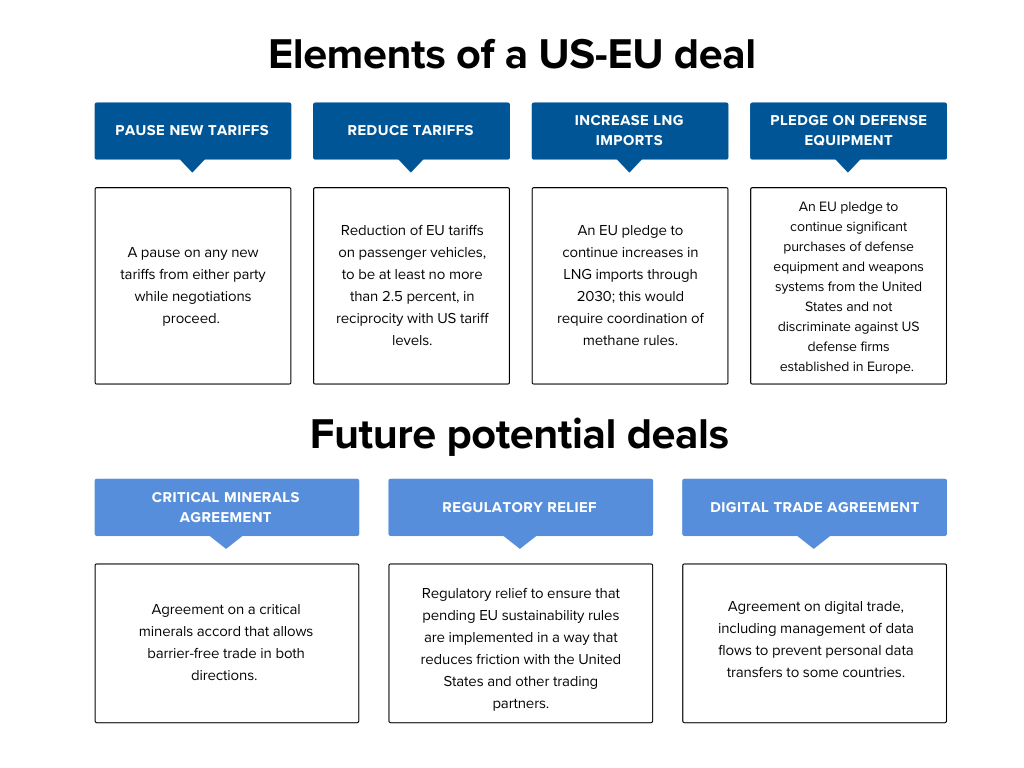

Leaders would do well to review the June 2018 deal between then EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and President Trump.8 In that statement, they agreed “to work together toward zero tariffs.” They also pledged not to “go against the spirit of this agreement,” which was widely interpreted as a “no new tariffs” pledge while negotiations were proceeding. Any new deal must begin with an understanding that new tariffs will not be imposed by either party in the wake of the deal, including the steel and aluminum tariffs announced on February 10. Ideally, one result would be to launch renewed negotiations to address the global steel and aluminum overcapacity issue—an issue of importance to both the United States and the EU—and remove those existing TRQs and threats of tariffs.

With tariffs put on the backburner, the deal must address the US trade deficit with the EU, and especially that of trade in goods. As mentioned above, in 2023 the US trade in goods deficit with the EU was significant, and it is on track to be even greater in 2024.9 But efforts to rebalance the number and type of goods traded across the Atlantic may be complicated by the high level of integration between the two economies. Much of transatlantic trade—perhaps as much as 65 percent by some estimates—is driven by strong mutual investment in which US and European companies have established major manufacturing facilities on both sides of the Atlantic.10 Thus, the direction and level of goods trade reflects supply chains in which auto parts, for example, move across the Atlantic several times during production of a finished product. Among the leading US imports from Europe are pharma products, chemicals, autos and components, and machinery. Similarly, the same industries are among the top US exports to the EU. Raising tariffs on EU imports in these industries could disrupt complex supply lines and may even complicate efforts to reduce the US deficit. Taxing components shipped by BMW in Germany to its US manufacturing facility not only raises the cost of a US-made car, but over the longer term threatens the cost-effectiveness of that facility and its jobs. Because BMW is the largest exporter of automobiles from the United States ($10 billion in 2021),11 the health of that factory is important to the reduction of the trade deficit.

Instead, a US-EU deal should seek to reduce barriers to trade in the sectors where trade is heavily integrated, while looking for additional US exports in key commodities. For example, one longtime point of contention between Washington and Brussels has been the EU tariffs of 10 percent on passenger vehicles. These apply to all EU vehicle imports—not just to US vehicle exports—except where trade agreements have been negotiated. The recently updated EU-Mexico trade agreement included a removal of the 10 percent tariff on autos that met a 60 percent threshold of EU or Mexican content.12 Despite the lack of a US-EU trade deal, this might be an opportune time to provide US exports with a waiver or suspension, especially given President Trump’s attention to this issue. The EU might take a page from Trump’s comments on reciprocity and reduce the tariff to the US level of 2.5 percent. Such a tariff reduction is unlikely to lead to a massive increase in cars entering from the United States as larger US vehicles have not proven popular in Europe. In 2023, the EU imported motor vehicles valued at approximately €10 billion from the United States (including US-manufactured German brands), while the EU exported automobiles totaling about €40 billion to the United States.13 A reduction in auto-related tariffs could be an important symbolic gesture, while not threatening the already struggling European car industry. Moreover, such a tariff reduction might lay the groundwork for a broader US-EU bilateral trade deal on auto parts and supplies.

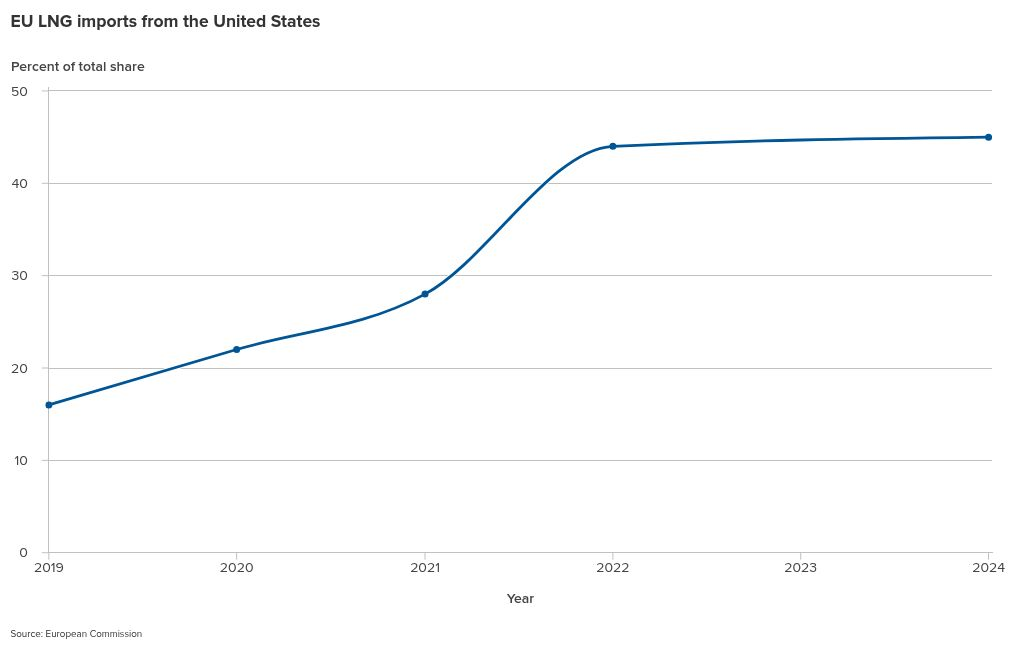

The key element in any US-EU deal would be for the EU to provide assurances of continued significant growth in energy-related imports from the United States, especially liquified natural gas (LNG). This was a major part of the 2018 deal between then-Presidents Jean-Claude Juncker and Donald Trump. In fact, US LNG exports to Europe have tripled since 2021, from 18.9 billion cubic meters (bcm) to approximately 56.3 bcm in 2023.14 Even as Europe reduces its overall gas consumption due to energy efficiency gains and a shift toward renewables, there remains significant potential for expansion of US exports, which now make up about 50 percent of EU LNG imports. Thus, any deal should include steps to reduce barriers to LNG trade so that trade can grow as much as the market allows. On the US side, the cancellation of the Biden administration’s suspension in licensing new LNG projects—accomplished on Trump’s first day in office—should reduce EU concerns about the long-term availability of US LNG.

On the EU side, a pledge that new regulatory measures will not hinder LNG trade should be considered. For example, efforts to foster carbon capture utilization and storage—which are expected to be launched under the new European Commission—should not create requirements that US-based exporters cannot meet. Similarly, the scope of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) should not be expanded to include LNG until after 2030. These are pledges that also preserve much-needed flexibility in European energy systems until renewables are sufficient.

Perhaps most immediately, consultations should be pursued to ensure that the EU’s new methane regulation does not inhibit the potential import of US LNG. Beginning in May 2025, that regulation establishes reporting requirements for importers, and in 2027 will mandate that EU importers ensure that imported LNG has been subject to methane reduction measures equivalent to those required in the EU.15 US methane regulations introduced by the Biden administration were a step in the direction of satisfying this requirement, but Trump is widely expected to rescind those rules. It may be that removing the financial penalties in the US rules but retaining other elements could provide a basis for a US-EU agreement that will allow US exports to continue unimpeded. A deal could include a pledge to begin consultations to resolve this challenging issue.

Finally, the EU could usefully add to the deal a pledge regarding defense procurement. European defense expenditures have grown significantly over the past three years and are likely to grow even more in the next decade. By some estimates, 80 percent of EU defense funds are spent on procurement from outside the EU, much of it from the United States.16 To date, the EU and its member states have provided more than €52 billion in military assistance to Ukraine.17 Making clear to the Trump administration how much the EU and its members plan to spend on US defense equipment over the next two to four years could be a significant element in a transatlantic deal. The EU could also pledge that there would be no discrimination against US defense companies established in Europe as it develops its EU defense industrial base.

Some may argue that such a deal will result in the EU giving more than it gets. That may be true, but these items also reflect Europe’s interests and likely behavior in any event: Importing LNG and buying weapons from the United States is going to happen. It is in the EU’s interest as much as that of the United States that methane requirements do not hinder the European supply of energy. And if removing a 10 percent tariff on US auto imports leads to an understanding that the United States will not impose more punitive tariffs on steel and aluminum, that would be a win for European industry.

Building a series of deals

Even if such a deal is reached, however, it will not fully resolve the trade tensions between the EU and the Trump administration. As a perpetual dealmaker, President Trump will soon start looking for the next deal that will reduce the trade deficit with the EU. The EU, in turn, will have to decide whether to engage. Depending on the situation, and the ambitions outlined by the United States, entering another negotiation may or may not support EU interests. However, there are some key areas where further deals might benefit both parties.

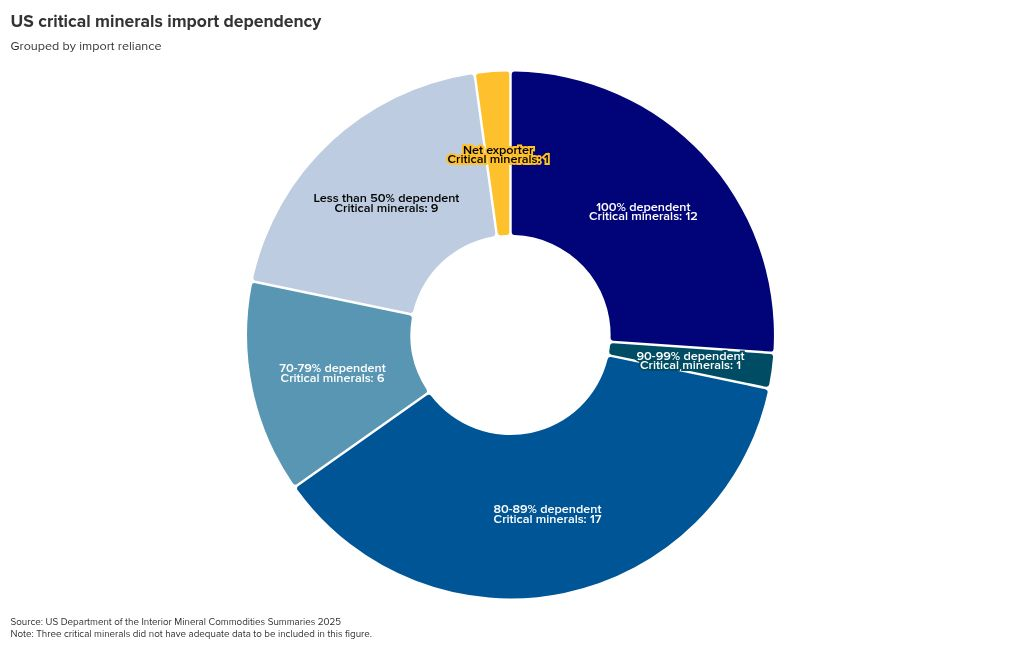

An area of increasing priority for both the United States and the EU is that of trade in critical minerals. Neither is a major producer of these commodities but rather must rely on imports to fulfill most of their needs. Extraction and processing of these minerals tends to be limited to a small group of countries, with China playing a large role. In 2022 the United States designated fifty minerals as critical to its economy, and China supplies more than half of US imports for nineteen of these minerals.18 The EU is in a similar situation, although it has set targets in its recent Critical Raw Materials Act to extract 10 percent of its annual consumption and process 40 percent of that consumption by 2030. It also envisions a major role for recycling of these commodities from used batteries, computers, etc.19 With the United States and the EU in similar straits, it makes sense to recognize any production from each other as suitable for barrier-free import into the other through an accord on critical minerals. The new administration is also unlikely to insist on the labor and environmental protections sought by the Biden administration in its version of a critical minerals agreement.

Aside from addressing the deficit in trade in goods, future US-EU deals could also include some key regulatory relief from European requirements for US companies. Too often, it is the regulatory differences that stifle US exports to Europe and increase the trade deficit. Europe has the right to regulate its own market and the products it allows into that market, as does any other jurisdiction. But while it is unlikely that any regulatory compromise could be achieved on such politically sensitive issues as GMOs or hormones in food, there are some pending rules in Europe that will cause serious transatlantic disruptions when they are enforced. Two key examples are the Deforestation Regulation (implementation was recently delayed until the end of 2025) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D), which is scheduled to be applied in mid-2027. The European Commission has launched an effort to “simplify” both regulations, but it is not yet clear what that potential reform will include.

In its current form, the deforestation rules require companies to certify that products they place on the EU market do not come from recently deforested land, including land outside the EU. The stringency of these rules varies depending on whether the country of production is at a high or low risk for deforestation. To date, the European Commission has not started rating countries according to risk, and there are questions about whether the United States will qualify for low-risk status. But because these doubts are mostly focused on the lack of forest preservation regulations—rather than actual data about the growth or decline of forest cover—the EU should consider providing flexibility in order to find a way to provide the United States with an early identification as a low-risk country.

CS3D requires companies in scope and operating in Europe to identify and address any adverse human rights or environmental impacts resulting from their business. Moreover, they are to ensure that their subsidiaries and business partners also adhere to these rules. For those companies with global supply chains—including US companies—this could have an enormous impact. An offer to open early negotiations between the United States and the EU about how to enforce this rule could help identify ways to ease its implementation. It should be noted that both the deforestation regulation and CS3D have received a significant amount of criticism from within the EU—including from the major center-right political group, the European People’s Party (EPP)—as well as support from companies who have already taken major steps to comply. Even if the EU moderates some of the provisions of these rules in response to domestic criticism, an early beginning to transatlantic discussions on implementation would be worthwhile.

Finally, another area of potential agreement between the EU and the Trump administration is that of digital trade. At its most basic level, this is about agreeing on requirements for digital invoices and other necessities for buying and selling goods online. Negotiations over such an agreement had been underway at the World Trade Organization (WTO) for some time. The Biden administration pulled out of those talks last year, saying that the essential security exemption was inadequate to allow restrictions on data flows to some countries. With the United States moving away from its long-time stance in support of free data flows, there is more opportunity for a bilateral agreement with the EU. While European data authorities have not shown much concern until recently about transferring data to countries such as China and Russia—compared to their focus on US data transfers—that also is beginning to shift. As a result, the prospects for a digital trade agreement between the United States and the EU have improved.20

This is hardly an exhaustive list of topics for a US-EU deal. While it is unlikely that a comprehensive free trade agreement is achievable, Germany’s designated chancellor Friedrich Merz has suggested this would be desirable.21 But even without such an umbrella agreement, there are opportunities for negotiating on specific topics. Key to identifying the most valuable areas for negotiation should be whether they improve the business climate across the Atlantic, and for the United States, whether barriers to US exports are reduced. A joint deal to resist Chinese overcapacity in steel and aluminum or to reduce the dangers posed by data transfers to China, whether in connected cars or through other modes, or an agreement on critical minerals that might boost US exports to Europe—these are just some of the specific arrangements that could be discussed. Initially a transatlantic deal might simply launch negotiations on such topics, giving both sides a further opportunity for hailing another agreement later. Even small deals can be instrumental in building some transatlantic good feeling, as demonstrated by the 2019 beef agreement, which was greeted with much enthusiasm by then-President Trump.22

Organizing such a deal will not happen overnight. It will involve weeks, if not months, of building a case for cooperation and then careful negotiation. The EU has made clear that it is willing to move down this path, as Trade Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič stated soon after Trump’s inauguration.23 President Trump began by announcing his America First Trade Policy but refrained from imposing trade penalties immediately. He then announced steel and aluminum tariffs but delayed their implementation until March 12—clearly opening a window for negotiations.

Beyond the deal

Even if the Trump administration and the EU succeed in concluding a deal, this will not resurrect the strategic partnership that has been central to transatlantic relations for the last seventy years. This will be a transactional US administration, and no single deal will lead to a long-term partnership. As with China, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Mexico, and others, Europe can expect the Trump administration to alternate threats with statements about the benefits of deals.

This method of operation is in part derived from the commercial real estate environment that is part of the president’s background. But it is also in keeping with the mood of the United States, as reflected in the 2024 election. Americans are largely focused on the domestic agenda, especially the economy and immigration, and they expect these to be the top priorities of the new administration. Whether it is justified by the data or not, many Americans believe that the economy is in poor shape and that trading partners have taken advantage of the United States.24 Thus, they are willing to give President Trump an opportunity to try his strategy of reducing access to the US market and seeking investments that will boost US industry. While polls show that many Americans are supportive of NATO,25 and believe the US should continue to support Ukraine,26 the election demonstrated that economic concerns far outweigh foreign policy—and even long-standing partnerships—as priorities for the American people.

As a result, Europe must prepare itself for a new US foreign economic policy, one based on transactionalism and nationalism. The EU as an institution will face some particular challenges. The Trump administration is likely to differentiate between European countries based on their trade surplus or deficit with the United States and the level of their defense spending. Individual member states may be offered opportunities for special deals with the United States, even though it is the European Commission that holds legal competence to negotiate such accords. The Trump administration’s closeness to key tech industry leaders will lead to challenges to EU digital regulation as well as to its competence in competition policy.

Thus, beyond being willing to negotiate a deal, the EU needs to demonstrate that it is a strong negotiating partner. Europe should be able to provide real benefits if a deal is reached, but also to exact costs if warranted. The EU’s trade defense measures are little understood in Washington and not viewed as a serious retaliatory capability, if viewed at all. Moreover, the EU’s recent trade deals with Mercosur (the South American trade bloc) and Mexico have not stimulated any concerns in Washington that Brussels might be gaining an advantage in international trade, despite the European Commission’s messaging on this point.27 Perhaps most importantly, sluggish European growth coupled with political weakness in two major member states (i.e., France and Germany) raise doubts about the value of Europe as an economic partner, despite the steady and significant increases in US-EU trade and investment. This skeptical attitude is only reinforced by the failure of Europe to grow global tech companies that would demonstrate prowess in the twenty-first century economy.

To be viewed by Trump’s Washington as an important economic and international actor, the EU must meet three challenges:

It must jump-start its economy. The current debate over competitiveness, grounded in the Draghi28 and Letta29 reports of 2024, is a good first step, but there must be real action and measurable change. Reversing a slow-growth economy will not happen overnight, but a significant reform of capital markets coupled with a genuine simplification of some regulatory requirements and a focus on expanding the already vibrant European start-up environment would be good indicators that change is underway. The new European Commission led by President Ursula von der Leyen must meet this challenge or the EU will become increasingly irrelevant in the eyes of US policymakers.

The EU, working with its member states, must clearly define its own interests. As the Trump administration is intently focused on the US domestic economy, the EU also must clarify its objectives and examine its priorities. It will not always be possible to pursue its own policy objectives while also aligning with the United States. Europe, for example, remains committed to decarbonization and the Paris accord, while the Trump administration seeks to ramp up fossil fuel production and restrict renewables. President Trump has a track record of relishing negotiations with those who act on their own interests first, such as China or Saudi Arabia. The EU should define what it wants from the United States and clearly understand its own position before entering negotiations with the Trump administration.

European rhetoric must also change. In fact, it has already started to do so, as President von der Leyen’s speech at Davos demonstrated, laying out a willingness to cooperate with the United States while also clarifying how EU interests and priorities may differ from those of the United States. With Trump in the White House, disagreement with the United States may become more normal for the EU, but European rhetoric should focus on issues that can be negotiated or that directly affect EU interests. In the past, European criticisms of the death penalty or lack of gun control in America only exacerbated tensions. Also, many Europeans tend to be intensely critical of their own governments, including the EU institutions. Politicians, think tank analysts, and leaders frequently complain in public and private about disunity within Europe and the EU’s slow political process. Whether one agrees with these criticisms or not (and for many US analysts, our own government seems even more divided and dysfunctional), voicing them will not convince the Trump administration that the EU will be a credible interlocutor.Mechanisms for a transactional relationship

European leaders and policymakers must be both realistic and imaginative about the mechanisms used to further US–EU discussions. Any deal is likely to create a need to launch consultations on specific issues, and there will be some who will use this to argue for a more comprehensive framework like the US-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC). However, it should be remembered that the Biden administration accepted the EU proposal for the TTC in part simply to affirm the importance of the relationship with the EU. The Trump administration has no such ambition and is unlikely to duplicate a mechanism that took considerable time from several cabinet-level officials. However, the first Trump administration did convene two US-EU dialogues—the Energy Dialogue and the China Dialogue—and was willing to engage in consultations when they could see a clear US interest. Despite differences over tariffs and other matters, there are numerous issues that could be discussed productively between the United States and the EU.30

During the second Trump administration, there are likely to be three distinct types of US-EU consultation mechanisms:

A very specific, working-level consultation that addresses a particular issue, including issues identified during high-level meetings. These may at times veer toward real negotiations. But they will be limited in addressing only the specific topic, and they are unlikely to evolve into a more institutionalized task force or ongoing discussions after the specific matter has been resolved.

A continuation of established but rather technical dialogues, such as the Joint US-EU Financial Regulatory Forum, which was established in 2016 as an enhanced version of the EU-US Financial Markets Regulatory Dialogue. The forum addresses money laundering, market stability, and banking oversight, as well as other financial market matters. But while the Financial Regulatory forum tackles issues of clear value to both the United States and the EU, the separate Joint Technology Competition Policy Dialogue probably faces a more uncertain future. Not only was it established during the Biden administration, but it reflects a desire on the part of both parties to use competition policy to restrain market-leading tech companies. While the Trump administration includes a range of views on tech and competition, it is unlikely to engage in a transatlantic discussion of competition policy while the president is criticizing Europe for fining US tech companies. Overall, these technical dialogues are likely to suffer, although some will survive. But without high-level encouragement, these are likely to be more restrained in terms of their scope and may become less frequent if leaders discourage staff from engaging.

A series of disconnected but parallel political dialogues, including the Energy, China, and Cybersecurity Dialogues. These are generally high-level dialogues, with a cabinet/commissioner-level leadership meeting annually and working-level continuing discussions throughout the year. In the past, they have been forums for discussion and debate, rather than negotiation, and have served to demystify decisions and build understanding, if not consensus. Such dialogues will either proliferate or disappear according to the interests of both the Trump administration and the EU. The Energy and China Dialogues are likely to persist, given the high priority both parties give to these issues. The Cyber Dialogue is also likely to continue and might be used to raise other technology-related issues where there is not enough harmony to convene a separate dialogue. Another potential dialogue could focus on Ukraine, including its reconstruction. In the absence of a comprehensive TTC-like forum, the question is whether these political dialogues could also address more technical issues. Could the Energy Dialogue, for example, work to address the potential conflicts in methane rules and other issues that could stymie future US LNG exports? Could the China Dialogue work to harmonize US and EU export controls on key technologies?Given the Trump administration’s hostility to the EU as an institution, this disaggregated set of mechanisms is probably more achievable and effective than something like the TTC. The trick will be to identify issues on which there is some congruence on US and European priorities. Where there is not—with US and EU views far apart on issues such as climate change, for example, and potentially AI—such dialogues would be less productive unless there is a concrete pledge to seek to ameliorate differences.

During the next four years—and perhaps longer—we can expect the transatlantic partnership, and especially the US-EU relationship, to undergo a sea change. Long established assumptions about strategic alliances and jointly protecting the world order will have to change. The Trump administration will expect the EU to act in keeping with Europe’s interests, and especially for the short-term benefit of the European economy. This is, after all, the Trump plan for the United States. Thus, when dealing with the United States, European leaders should worry less about having the United States understand and support their position and instead be clear in promoting Europe’s interests. They should also understand that while deals and agreements are possible, under the Trump administration they will not lead to a rejuvenated US-EU strategic partnership. The calculation of Europe’s value to the United States will begin again the next day. In the end, the best strategy for the European Union will be to grow its economy and strengthen the unity of its members. When the EU can present itself as a strong and coherent actor, with an economy that is recognized as key to the success of US companies, it will find more opportunities to engage with Trump’s America—and to do so on its own terms.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News