Iran’s strategic setbacks have enabled Türkiye to expand its influence in the Middle East, aggravating tensions between Ankara and Tehran.

Their rivalry has escalated even though they agree on major regional issues, such as the Gaza conflict and the broader Palestinian-Israeli dispute.

Türkiye’s leaders have warned their Iranian counterparts to refrain from backing Syrian groups at odds with the Sunni Islamist-led new regime, including some in the Alawite community and the Kurds.

Iranian leaders are concerned Türkiye will try to weaken Iranian influence in the Caucasus region further.

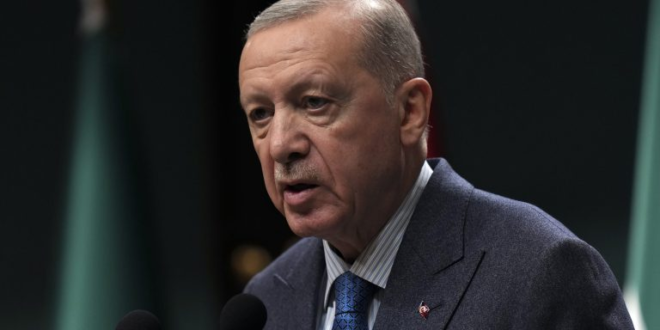

The recent military and political setbacks to Iran and its Axis of Resistance have upended the geopolitics of the Middle East, facilitating the rise of Turkish influence to fill the strategic vacuum left by Tehran. The dramatic power shift has aggravated longstanding tensions between Ankara and Tehran, as Türkiye seeks to protect its gains, primarily in post-Assad Syria, and to deny Iran the opportunity to revive its regional fortunes. The heightened tensions between Iran and Türkiye center on their competing drives to acquire preponderant regional influence and strategic depth – not on ideology. The Islamic Republic in Tehran and the moderate Islamist regime of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Ankara both identify vast U.S. military and financial support for Israel as a source of regional instability. Both oppose Israel’s tactics that have destroyed the Gaza Strip and strongly support the Palestinian struggle for an independent state.

Iran has actuated its opposition to Israel by materially supporting armed factions, including Hamas and Lebanese Hezbollah, as a “ring of fire” on Israel’s borders, attempting to render Israel insecure and non-viable. Türkiye, which is not only a member of NATO but fields the alliance’s largest standing army inside Europe, has generally confined its pro-Palestinian policy to issuing rhetorical threats against Israel and undertaking diplomatic efforts to discredit Israel. Even though the U.S. and its other European partners differ from Erdogan on the Middle East and many other issues, Western leaders largely welcome Türkiye’s expanded Middle East influence insofar as that advance comes at the expense of Iran. All Western leaders consider Iran as an adversary to be contained and marginalized. Still, U.S. and European officials, joined by partners among the Arab Gulf monarchies and other Arab leaders, remain wary of what they see as Erdogan’s neo-Ottoman ambitions.

The fall of the regime of President Bashar al-Assad has turned Syria, now led by Turkish-backed Sunni Islamists of the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) organization, into the key flashpoint between Ankara and Tehran, bringing their long-simmering competition for regional influence out into the open. Iranian civilian and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) leaders have openly acknowledged to the Iranian population that Assad’s collapse constituted a major strategic blow to the Islamic Republic. Aligned with their U.S. and European counterparts, strategists in Ankara are concerned the IRGC will try to employ Tehran’s standard “playbook” – creating, arming, funding, and advising non-state armed actors – to try to rebuild its influence in Syria and undermine the Turkish-backed government in Damascus. Türkiye assesses Iran seeks to potentially restore to power a pro-Iranian regime in Syria or, at the very least, to rebuild secure routes in Syria through which to rearm its main regional ally, Lebanese Hezbollah.

Distrusting Iran’s intentions in Syria, Ankara has reacted sharply to seemingly unconnected clashes in Syria, involving fighting between Damascus’ forces and members of Assad’s Alawite community and battles between Kurds and Ankara-backed Arab factions. In a February 26 interview on Al-Jazeera, Türkiye’s Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan warned Tehran against any meddling in Syria, saying such action would “not be the right” approach, adding, “If you try to create instability in another country by supporting a certain group, then another country may do the same to you in return.”

Tehran reacted angrily to the implicit threat. At his weekly press briefing on March 3, Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmail Baqaei called Fidan’s “unconstructive” comments, saying: “The results of recent developments in the regions become clearer by the day…Our Turkish friends need to reflect on the consequences and impacts of their policies.” On March 4, the Ministry met with Türkiye’s Ambassador to Tehran, Hijabi Kirlangych, after which deputy Foreign Minister Mahmoud Heidari stated: “The common interests of both countries and sensitive regional conditions require avoiding inappropriate statements and unrealistic analyses that could lead to disputes and tensions in bilateral relations…” Heidari added, appealing to their shared views: ”It is expected that the major Islamic countries will focus all their efforts on stopping the crimes and aggression of the Zionist regime against the oppressed people of Palestine and other countries in the region, including Syria.”

Fidan’s warning reflected Ankara’s fears that Kurdish forces in Syria might seek Iranian assistance in their battle against an Ankara-backed militia, the Syrian National Army (SNA). Since the fall of Assad, the SNA has been militarily pressuring the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) – the U.S. partner combatting Islamic State (ISIS) fighters in northeastern Syria – as part of an effort by Ankara to expand a buffer zone along the border with Syria. Türkiye intends the zone to prevent Syrian Kurds from actively supporting their ethnic brethren inside Türkiye. Yet, there is no hard evidence, to date, that Iran has sought to provide military support to the SDF or any other Kurdish factions. Still, some Tehran-based experts assessed that such a move by Iran, if implemented, could serve the dual purpose of counterbalancing Turkish influence and gaining leverage over Damascus’s new rulers.

Fidan’s comments also sought to deter Iran from supporting members of the Alawite community concentrated in Latakia and Tartus provinces, along Syria’s Mediterranean coast, which formed the backbone of Assad’s regime. The Alawites have an affinity for Iran because of Tehran’s long alliance with Assad and the Alawite adherence to a version of Shia Islam. Last week, a Damascus “security operation” involving HTS fighters and other Syrian military personnel moved to crush Alawite dissent, triggering several days of clashes that killed more than 600 on both sides. There is no direct evidence that Iran has stoked violent Alawite dissent, but Turkish and Western experts note that the Alawites would be useful to efforts by Tehran to restore rule by Assad or another pro-Iranian Syrian leader. During the fighting, some Alawite civilians sought refuge at the Hmeimim military base still used by Russian forces, even though much of the Russian force left the base after Assad’s collapse. Another minority community, the Druze, concentrated in southern Syria, has formed armed militias to challenge Damascus’ authority, but the Druze appear to be looking toward Israel, not Iran, for protection from HTS.

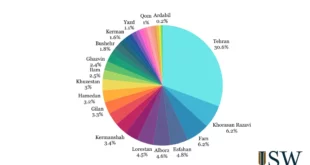

For its part, Tehran is concerned Ankara might seek to extend its influence into Iranian territory itself as part of an effort to strategically marginalize Iran. A paper closer to Iran’s dominant hardline faction, Jahan News, said on March 1 that Foreign Minister Fidan’s “delusion has led to his arrogance” and challenged Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi to “remind Fidan of Türkiye’s place and Iran’s power.” A more moderate Iranian daily, Hammihan, argued in a March 2 article that Erdogan is “under the impression that Iran is weak after suffering setbacks in recent months.” The paper urged Iranian authorities to give a “clear response” to Türkiye and “permanently neutralize” Erdogan’s “game.” Another moderate outlet, Shargh daily, charged that “state-linked” Turkish social media accounts were fanning separatist sentiments among ethnic Azeris in Iran, who constitute as much as 20 percent of Iran’s population, and stoking anti-regime sentiment among Iranian Kurds in a bid to “sow division” within Iran. Other Iranian outlets noted that the recent declaration by the anti-Ankara Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) to cease the armed struggle against the Turkish state constituted a defeat for Tehran and another illustration that Türkiye has gained the upper hand in the region.

Iran also fears potential Turkish aggression in other areas of the region in which Iran is vulnerable. Iran and Türkiye have long been competing for influence in the South Caucasus, which Iran considers part of its historic sphere of influence. Azerbaijan’s recapture of the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh enclave in its 2020 war with Armenia shifted the balance of power in the region toward Türkiye-backed Baku. In a renewed flareup of that conflict in 2023, Baku emerged victorious with Turkish support, in the process securing access to the territory for a proposed Zangezur Corridor — a transport route that would link Azerbaijan to its non-contiguous enclave of Nakhchivan as well as to Türkiye. Tehran staunchly opposes establishing that Corridor, viewing it as an Ankara-backed ploy by Baku to sever Iran’s direct land connection to Armenia — a historical ally of Iran and adversary of Azerbaijan and Türkiye. The establishment of the Zanzegur Corridor would also reduce Armenia’s reliance on Iran for energy and transport, further diminishing Tehran’s influence as well as constituting a blow to Iran’s standing and prestige.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News