Iranian leaders fear that Türkiye, emboldened by the ousting of the Assad regime in Syria, will further advance its influence in the South Caucasus at the expense of Iran.

Iran’s foreign minister visited Tehran’s key South Caucasus ally, Armenia, last week to coordinate efforts to thwart the establishment of a Turkish-backed transit corridor that would block Iran’s land access to Armenia.

Recognizing its declining relationship with Russia and Tehran’s recent setbacks, Armenia has moved closer to the United States and Europe and tacitly shown signs of improving relations with Türkiye.

Iranian leaders fear that further signs of weakness could invite the U.S. and/or Israel to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities.

Iran’s geostrategic setbacks in the Levant since September, highlighted by the ousting of the Assad regime in Syria by Islamist rebels aligned with Türkiye, have set Iran’s diplomats working intensively to stanch further hemorrhaging. Iranian leaders sense particular vulnerability in the South Caucasus, where Türkiye has been ascendant since well before the fall of Assad. Two offensives by Ankara’s close ally, Azerbaijan, in 2020 and 2023, both of which were propelled by extensive military help from Ankara, allowed it to gain full control of the disputed territory, Nagorno-Karabakh. The territory had been largely inhabited by ethnic Armenians but was internationally recognized as a part of Azerbaijani territory, although being de-facto governed by a separatist Armenian-backed government. As a result of Azerbaijan’s 2023 military take-over, more than 100,000 Armenians fled the enclave, an exodus widely characterized by Armenia as ethnic cleansing. Azerbaijan had earlier lost control of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia in 1993, in warfare that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet Union.

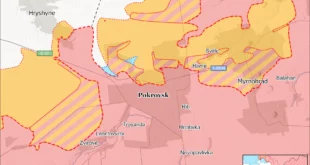

Lacking a clear pathway to challenge Turkish hegemony in post-Assad Syria or to quickly rebuild its other regional allies, particularly Lebanese Hezbollah, Iranian leaders are trying to resist further expansion of Turkish influence in the South Caucasus. In particular, Iranian officials fear that Türkiye’s success in Syria will embolden Ankara to help Baku push forward on a long-planned initiative – the Zangezur Corridor – to establish a land transportation route linking the Azerbaijan mainland to the non-contiguous Azeri exclave of Nakhchivan. The Zangezur Corridor, should it proceed, would traverse southern Armenia, close to the Iranian border, and would in essence cut Iran’s land route to Armenia.

Iran assesses that the Zangezur Corridor initiative, if it proceeds, would constitute a threat to Iran’s influence in the South Caucasus, and affirm Iran’s diminished regional leverage relative to Türkiye. Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi arrived in Armenia last Monday, ostensibly to shore up bilateral ties, but in practice to coordinate Iranian and Armenian efforts to thwart the Zangezur project. More broadly, Araghchi also sought to reassure his Armenian counterpart, Ararat Mirzoyan, that Tehran’s recent setbacks will not affect its ability to support Armenia, and that Iran will not willingly accede to Turkish hegemony in the South Caucasus or the broader region. Araghchi’s message of reassurance acknowledged that Armenia’s leaders were severely shaken by the lack of effective support from either Russia or Iran in the recent conflicts with Azerbaijan. During the October 2023 combat, Moscow’s 2,000 Russian peacekeeping forces in Nagorno-Karabakh – there under agreements that settled the 2020 round of fighting – offered almost no resistance to Baku’s offensive. In fact, many experts believe that Russia was aware of, and gave tacit approval to, Azerbaijan’s 2023 takeover. The Russian contingent also withdrew from the enclave entirely in April 2024, one year ahead of schedule.

Nor did the Islamic Republic intervene to help beleaguered Armenian forces, even though Iran’s alliance with Christian Armenia has been a core component of Tehran’s regional policy. Although most of the inhabitants of both Iran and Azerbaijan are Shia Muslims, the two governments have been at odds since Iran’s 1979 revolution. They differ over the role of Islam in politics, and Iran has periodically accused Baku of stoking ethnic Azeri separatism within Iran. Iran has also criticized Azerbaijan for hosting Israeli special operations and intelligence personnel that have helped Israel identify Iranian targets and conduct repeated successful covert operations inside Iran. Nonetheless, Iran and Azerbaijan have moved to improve relations in the past year, as have Iran and Türkiye. Azerbaijan reopened the embassy in Tehran last July, and the two countries held joint military drills in November.

Araghchi’s visit to Yerevan also perhaps sought to slow or halt Armenia’s search for alternative alliances and relationships as its confidence in Moscow and Tehran wanes. Iranian leaders are particularly concerned that Armenia, unsatisfied with its ties to Russia and Iran, is turning toward the United States as a potential partner. In January, one week prior to Donald Trump’s second inauguration, Armenia officially joined the US-led Global Coalition to Defeat the Islamic State (ISIS) and signed a Strategic Partnership Framework with the United States. The agreement outlines enhanced cooperation between the two nations, focusing on economic and security collaboration, the promotion of democracy, justice, and inclusivity, and fostering cultural and educational exchanges.

Armenia also has been moving closer to the European Union. The EU and Armenia held a joint meeting in Brussels in April 2024 aimed at improving ties. Yet, Armenia’s turn toward the West also depends on permanently settling its conflict with Azerbaijan and, ultimately, improving relations with Türkiye. Turkish officials have stated their willingness to open the border with Armenia — provided they receive approval from Baku. Direct trade with Türkiye would significantly boost Armenia’s economy and more closely integrate Armenia’s economy with that of Europe. Bowing to those needs, in mid-March, Armenia and Azerbaijan agreed to general terms of a treaty that would end the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh and other border territories, including Syunik (where the Zangezur corridor would be built). The treaty, outlined but not yet signed, appears to represent an admission by Armenia that it “lost” the conflict with Azerbaijan. That recognition is certain to further embolden Türkiye, whose weapons were key to Azerbaijan’s success. In negotiations to finalize the text, Baku is demanding Armenia amend its constitution to remove a reference to the country’s Declaration of Independence — a document that includes a call for unification with Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijani officials reject their Armenian counterparts’ arguments that modifying the constitution requires a nationwide referendum far from guaranteed to obtain a vote of approval.

A major question is whether Iran, fearing further Turkish encroachment on its vital interests, would try to interfere – or is capable of interfering – with Armenia’s turn toward the West or its improvement of relations with Türkiye. To date, Iran has not signaled it would try to derail any of Armenia’s initiatives, but Iran could try to limit any benefits to Turkish geostrategy from Armenia’s shifts. Iranian leaders recognize that Armenians are desperate to avoid another war against Azerbaijan. The repeated fighting in recent years, as well as the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh, has left Armenians fearful of a new, even larger conflict that could threaten not just their homes but the existence of the Armenian state. This fear is not unsubstantiated, as Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev has repeatedly made irredentist and inflammatory remarks about Armenia, labeling the Syunik region as “Western Azerbaijan,” and consistently reporting cross-border fire on Azerbaijani military positions during negotiations — many of which have been unverified or contested.

On the other hand, having lost its ally, Assad, in recent months, Tehran does not want another partner, Armenia, to fall further under the sway of its adversaries in Ankara and Washington. Armenia’s firm alignment with the West would further the regional perception that the Islamic Republic’s strategic position is in a steady decline, and that additional pressure can be put on Tehran with impunity. Although the many strategic setbacks Iran has suffered in the past year poorly position Tehran to determine the direction of Yerevan’s diplomacy, both Iranians and Armenians recognize the growing unpopularity of Armenia’s current administration. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan is widely seen as weak and susceptible to foreign influence, and the proposed peace deal with Azerbaijan is deeply unpopular among the Armenian public — a dynamic that could benefit Iran’s regional strategy. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan has shown signs of undermining the agreement, hesitating to sign even a deal that heavily favors its interests. A collapse of the peace process — which remains a real possibility — could strain Yerevan’s emerging ties with Ankara and Washington.

Perhaps above all, Iranian leaders fear that a perception of weakness could further tempt Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and/or President Trump to strike at Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, invite other aggression, or embolden the domestic opposition. Iranian leaders are looking for opportunities to demonstrate they have the leverage to deter actions and policy decisions by their adversaries – whether in Türkiye, Azerbaijan, Israel, or the United States – that threaten Iran’s national interests. If Iran were to succeed in thwarting the Zangezur transit corridor, that outcome might represent a step forward for Iran in reversing its strategic downturn. But, emblematic of the diplomatic, economic, and military weight that Iran’s adversaries can bring to bear, Türkiye’s Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan met with U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio in Washington, D.C., just as Foreign Minister Araghchi was meeting with Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan in Yerevan. Although the Rubio-Fidan meeting did not specifically focus on Iran or the South Caucasus, Iranian leaders are well aware that, despite Turkish-U.S. differences on many issues, Türkiye is a member of the NATO alliance – a partnership that Ankara perceives entitles it to preponderant influence in the region.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News