More than 122 million people have been forcibly displaced, according to the UN Refugee Agency as of June 2024 — an increase of 5.3 million, compared to the end of 2023. Those fleeing are being pushed out by persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, and breakdowns in public order. The numbers are expected to soar tragically higher now, given continuing crises globally, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gaza, and Sudan, among other places.

Displacement is one of the most pressing humanitarian concerns today. People may be displaced within or across international borders. Individuals move for multiple and complex reasons, but armed conflicts are triggering a massive displacement of people searching for safety, shelter, and support. Internal displacement due to conflict and violence alone had already displaced 72.1 million people by mid-2024.

Beyond the immense loss of lives and suffering from injuries, armed conflict devastates individuals and communities in many other ways. The physical and mental hardship that those caught in armed conflict experience is compounded when they are displaced, especially if they are displaced repeatedly or for a prolonged period. They lose their homes, possessions, livelihoods, and sense of safety. They may not have access to basic services and supplies essential for survival, such as water, food, power, and healthcare. For displaced children and youth, interrupted education and lost learning have far-reaching repercussions. Displacement also fractures families and the social fabric, with intergenerational effects.

Forced displacement is generally understood as the involuntary movement of people from their normal residences, fleeing conflict, violence, persecution, or other adverse conditions and events. It is more than just a descriptive term; it also carries legal meaning. Forced displacement is generally prohibited under international law and may even constitute an international crime, although international law also foresees some limited circumstances where forced displacement may be tolerated and not unlawful. However, these provisions can be abused or misused.

Understanding when and how forced displacement may be unlawful and therefore punishable equips reporters with important legal context and language, ensuring that critical issues are analyzed. This is important not only for judicial accountability for potential violations and crimes; it also contributes to critical documentation and more accurate reporting.

This chapter distills some essential elements of reporting on forced displacement, aiming to simplify complex legal concepts. There is no one definition of forced displacement in law or otherwise. Within the law, forced (or forcible) displacement is often treated as a general term to refer to certain acts prohibited (and, under certain conditions, criminalized) by international law. Definitions of the specific acts are a patchwork of partially overlapping and sometimes inconsistent meanings. For simplicity, in this chapter, forced displacement and forcible displacement are both treated as substantively similar, referring to involuntary displacement.

Legal Protections Against Forced Displacement

Protections against forced displacement can be traced as far back as 1863, in the first attempts to codify laws of war in the Lieber Code, during the American Civil War. The Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg), established in the aftermath of the Second World War, listed deportation as war crimes and crimes against humanity.

As elaborated in other parts of the GIJN Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes, international humanitarian law (IHL) is the part of international law that regulates armed conflicts — both international and non-international. These rules can be found in treaty law (mainly in the 1949 Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocols of 1977, and the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907) as well as in customary rules of IHL that are general practice accepted as law.

IHL seeks to balance the preservation of humanity with military necessity, by imposing limits on permissible conduct in armed conflicts to prevent unnecessary suffering.

“Forced displacement,” as such, is not specifically defined in IHL. But it is used as an umbrella term to cover certain acts relating to the involuntary movement of people prohibited in armed conflicts.

Put simply, IHL prohibits forced displacement of the civilian population (in whole or in part) by parties to an armed conflict unless either the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons so demand. This captures the essence of the rule protecting civilians from forced displacement, which exists within both international and non-international armed conflicts, and reflects customary law (binding regardless of their ratification of the relevant treaty).

The classification of the conflict as either an international or non-international armed conflict determines the applicable rules.

Under the law governing international armed conflicts, deportations or forcible transfers of “protected persons” from occupied territory are prohibited, as contained in Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Strictly speaking, this rule applies specifically to an occupying power (a party in effective control of foreign territory and with the capacity to forcibly displace), regulating forced displacement occurring in situations of occupation (but not necessarily applicable to other international armed conflicts). “Protected persons” are civilians who find themselves in the hands of a party to an international armed conflict of which they are not nationals, and are protected under the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Forced displacement can take two forms: externally, across national or territorial borders, or internally, within such territory. Deportations refer to forced displacement across borders, and forcible transfers refer to forced displacement within borders. The terms “refugees” and “internally displaced persons” are also often used to refer respectively to those who have been displaced across or within national borders. (Refugee status determination has other protective functions.)

Violation of the prohibition on deportations and forcible transfers is a grave breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention and the First Additional Protocol. Grave breaches are particularly serious violations of IHL, and a type of war crimes. (A grave breach engages a legal duty for all States to extradite and prosecute perpetrators.)

Under the law applicable during non-international armed conflicts, it is prohibited to order the displacement of the civilian population, as enshrined in Article 17 of the Second Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions. While the Additional Protocols have not been universally ratified, the prohibition of forced displacement reflects customary IHL and, as such, is binding on all parties to the conflict (States as well as non-State armed groups).

Violation of the prohibition of forced displacement may also constitute international crimes, notably, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The understanding of these offenses have been developed in jurisprudence, particularly in the case law of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The tribunal prosecuted various displacement crimes: for example in Prosecutor v. Krstić, Prosecutor v. Krnojelac, and Prosecutor v. Naletilić & Martinović.

In the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, there are several provisions under which acts of forced displacement are explicitly listed as potential crimes. Various acts of forced displacement are listed as war crimes in both international armed conflicts (article 8(2)(b)(viii)) and non-international armed conflicts (article 8(2)(e)(viii)). Acts of forced displacement, if committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack, could also constitute crimes against humanity. The deportation or forcible transfer of population is explicitly enumerated as one of the acts of crimes against humanity (article 7(1)(d)). Historically, acts of forced displacement have also been tried as a basis for persecution and other inhumane acts (such as in the cases of Prosecutor v. Kupreškić et al. and Prosecutor v. Krnojelac).

What Qualifies as ‘Forced’?

The essential element of violation of the prohibition of forced displacement is the involuntary nature of displacement. As such, understanding what constitutes “forced” is critical.

The key question is whether the act of displacement was the result of real choice or induced by force or coercion. In examining force in this context, it is not limited to the actual use of physical force and should not be interpreted restrictively. It includes threats of force or coercion, such as that caused by fear of violence, duress, detention, psychological oppression or abuse of power, or by taking advantage of a coercive environment (Trial Judgment of the Krnojelac case, paragraph 475). Coercive circumstances would make true consent and real choice impossible (Trial Judgment of the Naletilić case, paragraph 519). In such cases, any alleged consent is hollowed of meaning.

In practical terms, this could include direct action taken to physically remove civilians from an area against their will or, occur indirectly, by making staying impossible. The ICTY has determined that a lack of genuine choice can be inferred from threatening and intimidating acts calculated to deprive the civilian population from exercising its free will, such as shelling or burning of civilian objects, and (threatening to commit) other crimes calculated to terrify the population forcing them to flee (Trial Judgment of the Simić case, paragraph 126).

When Might Forced Displacement Be Lawful?

Lawful evacuation is the only exception to the prohibition of forced displacement. There are only two lawful grounds that may necessitate evacuations:

The security of the population: when circumstances pose such grave danger to civilians they have to be evacuated for their safety, such as when an area is liable to be subjected to intense bombing. Such danger to civilians cannot be the result of unlawful acts by the parties themselves. For example, a party to a conflict cannot possibly justify forcible displacement by carrying out indiscriminate attacks.

Imperative military reasons: when overriding military considerations justify displacement, a qualifier that reduces such cases to a minimum. Such overriding military considerations still have to be lawful objectives. Misusing evacuations as a pretext to justify forcible displacement in pursuance of unlawful objectives, such as ethnic cleansing, would be unlawful.Where displacement is of a forcible nature and not justified under one of these exceptions, it is unlawful. Evacuations also must be temporary (only for as long as the reason justifying them lasts), otherwise they are unlawful.

There are circumstances where evacuations may genuinely be required to protect civilians. For example, civilians may be removed as a precautionary measure against the effects of attacks in compliance with the rules regulating the conduct of hostilities. In these situations, where advance warnings are given to the civilian population prior to an imminent attack, these warnings have to be effective and enable safe evacuation. The strict conditions for lawful evacuations must still be met for the genuine protection of civilians, to avoid the misappropriation of humanitarian principles for mass displacement.

It must be emphasized that IHL only tolerates forced displacement under very narrow and specific circumstances. These should be treated as exceptional and temporary measures. It would also be fundamentally contrary to the humanitarian object and purpose of IHL to exploit such a provision.

The fact that the displacement of civilians is labelled as an evacuation (by the parties to the conflict or other actors) does not automatically legitimize it. The forced relocation of civilians would qualify as a lawful evacuation only if it is undertaken for one of these lawful grounds and meets the cumulative legal conditions:

Displacement has to be limited internally, within the bounds of the territory. In occupied territory, the displacement of protected persons must be kept within that territory unless it is physically impossible. In non-international armed conflicts, displacement must be within national territory.

Displacement must be temporary and evacuees may (voluntarily) return to their homes once hostilities in the area have ended and the reason for evacuation has ceased. This presumes that it would indeed be possible to return, and the area(s) would not be uninhabitable, despite the effects of the armed conflict. This is consistent with respect for the rules regulating the conduct of hostilities that protect civilian objects and specifically objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population.

To the greatest practicable extent, there must be satisfactory conditions (shelter, hygiene, health, safety and nutrition), and families must not be separated.The range of protection in relation to forced displacement covers prevention of acts of displacement, geographical and temporal restrictions on displacement, the treatment of those displaced, as well as the return of displaced persons. If any of these cumulative conditions safeguarding the affected population are not met, the forced displacement would be unlawful.

Tips and Tools

When reporting about situations where there is potential concern of forced displacement, a number of guiding considerations are suggested.

Understand the substance of the relevant legal protections. It might be difficult for journalists to conduct a high-level legal analysis of the classification of the conflict, and determine certain conduct as a specific violation. It would be useful to seek reliable expert legal analysis in this regard, but it would be practical to establish a baseline understanding of the main elements of the legal protections.

What are the relevant rules that apply to the parties in conflict?

What are the rules designed to do?

Who does it protect?

What are the components of protection?

What are the sources of these rules and how are they interpreted?Collect relevant data on forced displacement. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) consolidates the statistics of forcibly displaced people across the world, with spotlights on key displacement situations. Beware, UNHCR data on forcibly displaced persons does not establish the displacement as a possible crime; it is factual rather than legal.

Gather facts and document patterns. Use a variety of sources to gather and corroborate facts.

Collect testimonies of the displaced, which may be available through organizations operating in the context providing services and other forms of assistance. Ensure that where interviews are conducted, these are trauma-informed and survivor-centered. Verify facts and details about known events and locations with available documentation, which may include audiovisual material captured by those displaced.

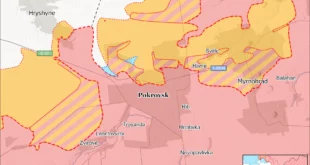

Open source information may be a helpful and critical complement for investigations, especially in locations where access is denied or otherwise unavailable. If you’re investigating a specific conflict, look for open source material online. Photos and videos available from agencies as well as those posted by people who are in or displaced from/to the areas of concern can help establish a picture of facts on the ground. Other types of open source information can also provide a different visual perspective to the investigation. For example, satellite imagery was used extensively in this 2024 Human Rights Watch report to analyze damage and destruction and track displacement patterns inside Gaza. Guidance on using open source research for investigations can be found in this chapter of the guide.

Official statements and other material from the parties to the conflict are an important source of information for investigative analysis. This includes press statements, interviews published in local languages, directives and other communications directed at the civilian population caught up in the conflict, social media posts by official bodies, and foot soldiers sharing recordings of their military action. These can help to provide a more holistic picture of the interests and behaviour of those involved in the conflict – their operational approaches, purported positions and policies, practices and apparent conduct, and attitudes toward IHL norms. This could also help identify who may be responsible for forced displacement.Analyze the circumstances of displacement. Observations about displacement can be informed by these questions:

What is the context to the displacement?

What are the potential reasons for the displacement? Are there indications that the displacement may have been ordered, forced, or coerced by one of the parties to the conflict?

What alternative possibilities exist for civilians to seek safety? What are conditions like in alternative places of safety?

Were there safe routes for people to move? Were they given sufficient time?

Where were people displaced to?

For how long were people displaced? Did people return?

What are the displacement trends, patterns, and scale?Identify useful indicators. Pay attention to both actions and omissions. Both can offer useful indications regarding the legality of the displacement.

What signs point to force or the threat of force driving the displacement, if any? What are possible factors contributing to a coercive environment? Can intent to forcibly displace be deduced or inferred?

What relevant facts can be used to evaluate possible lawful justifications for the displacement?

What do the circumstances of the displacement indicate about respect for the geographical and temporal restrictions on evacuations and the material conditions required? Does the duration of displacement indicate temporariness? What are possibilities for return? Were people displaced across borders? If so, what were the reasons? How can the adequacy and quality of shelter, hygiene, health, safety, and nutrition be evaluated?

What is the general attitude and adherence of the parties with IHL? How do their policies and practices confirm this? What information is available about the initial assessment of their compliance with IHL?Refer to human rights and humanitarian organizations. There is a diverse range of human rights and humanitarian organizations with specific contextual and thematic expertise, from local organizations to UN agencies, and international fact-finding and investigative mechanisms. Their expert analysis, including legal analysis, can help journalists investigating forced displacement. This includes reports from UN Human Rights Council-mandated investigative bodies, digital investigative teams in human rights organizations, information and commentary from organizations and experts with legal expertise.

Case Studies

Humanitarian Violence in Gaza, Forensic Architecture.

This study documented the mass displacement of Palestinian citizens by the Israeli military in the Gaza Strip and analyzed the systematic violence and destruction. The investigation selected pertinent information outlining the circumstances of each phase of displacement identified and the ensuing harm inflicted on civilians, to support the conclusion that the displacements did not meet the legal criteria qualifying as “evacuations”. The findings challenged Israel’s argument (in January 2024) that it was evacuating civilians from areas of hostilities and undertaking humanitarian measures to mitigate harm, in the ongoing legal proceedings of South Africa v. Israel before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). There was reportedly no response from Israel to a request for comment on the Forensic Architecture investigation. The Court has confirmed “forcible displacement of the vast majority of the population” and its concerns about the immense risks to the Palestinian population, ordering provisional measures following requests by South Africa (and this investigation was used as a source of supporting evidence).

Uprooted, The Kyiv Independent.

This story investigated the deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia, identifying the names of some individual officials responsible and locating the whereabouts of some of the children. This investigation is highlighted for its focus on the forced displacement of children and its emphasis on the responsibility and liability for the crimes. In 2023, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Russian President Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin and Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Alekseyevna Lvova-Belova for their roles in the unlawful deportation and unlawful transfer of Ukrainian children. While Russia has denied any wrongdoing and dismissed the arrest warrants, these individuals risk arrest by other States when they travel (since States parties to the ICC are obliged to cooperate).

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News