Case Study: The migration wave and the Schengen agreement

Most of the observers of the Middle East have become used to the talk about a new Middle East. They did so after the Camp David accords, the Oslo Agreements and most recently the Arab Spring. In the end, it resulted in the same old Middle East, plagued by war and chaos.

Current situation assessment

The recent developments show, as in the past, a changing diplomatic, strategic and military landscape of the Middle East, marked by the consequences of the vacuum left by an indecisive, often confused American and Western policy in the region. We are assisting – unsurprisingly – to a process in which this vacuum tends to be filled by new (and old) power actors, led by Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

The current phase of the Middle East conflict – marked by the Syrian war but also by the persistence of the older conflicts – is already called “World War IV”, since some analysts consider the many wars under the umbrella of the Cold War to have been World War III. The catastrophic civil war in Syria triggered two international crises: the exodus of Syrian refugees arriving in Europe; and the expansion of the terrorist group Daesh which controls a significant territory of Syria, where it enforced a new kind of state structure, and threatens to change the existing borders designed after World War I.

Russia’s recent escalation of its military intervention in the Middle East by firing long-range SS-N-30A Kalibr cruise missiles against targets in Syria from surface ships in the Caspian Sea is only the Kremlin’s most recent “message” about its real geopolitical intentions.

Analysts at the Royal United Services Institute point out that, while cruise missiles are not suitable for strikes against the mobile or fleeting targets that are to be found in Syria, they are, however, excellent demonstration weapons to show that Russia can deliver significant firepower over very long ranges.

Cruise missiles capable of striking in Syria from the Caspian Sea could also potentially strike most targets in the Middle East, including many of the bases used by the US-led coalition to conduct operations over Iraq and Syria. By being able to pose a credible threat to coalition air assets over large parts of Syria, Russia forces the US and its allies to consult with it on mission planning and deconfliction efforts.

All of this is aimed at forcing the US and its allies to accept Russia as a central geopolitical actor in the Middle East, which must be consulted and included in any efforts to alter the current situation by new means.

Another significant aspect is that the SS-N-30A used in the recent strikes is thought to be the basis for the new SSC-X-8 cruise missile, which is part of Russia’s Strategic Nuclear Forces and is considered by the U.S. as violating the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty signed by the U.S. and the Soviet Union in 1987.

Given the tense state of NATO-Russian relations over Syria, Crimea and Ukraine, a large-scale, live-fire demonstration of the SS-N-30A – that ranges within the scope of the INF treaty – could be seen as a covert Russian confirmation that their SSC-X-8 can also fly well beyond 500 km, and thus, a reminder that Putin continues to disregard the greatest arms control success of the Cold War.

Gradually, Kremlin’s offensive prompted a “softening” of the West’s attitude. State Secretary Kerry, while maintaining the U.S. position that Assad has no place in Syria’s future, indicated that keeping him around for a period of time was negotiable. The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, was more generous towards Assad saying “we have to speak with many actors, this includes Assad…”

Russia’s military build-up in the region has triggered moves by all the major players. In recent months and weeks leaders and representatives of Iran, the Arab Gulf states, Egypt, Israel and Turkey went to Moscow to discuss the future of a region on the verge of a meltdown.

Following a recent meeting with Putin, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan also appeared to have fallen into Putin’s circle of thought, saying Assad could take part in the transition process. Erdoğan also referred to a “triple initiative” among the United States, Turkey and Russia plus Syria, which could also include Saudi Arabia and Iran.

The fact that Turkey is well aware of Russia’s geopolitical superiority and its own economic interest in the bilateral relationship was revealed by Prime Minister Ahmed Davutoğlu’s recent statement – following the violations of Turkish airspace by Russian fighter jets – that “Russia is our neighbor and friend, and our interests do not conflict.”

The same idea was later to be mentioned after a meeting between Vladimir Putin and French President François Hollande, when it was suggested that Russia also cooperate with “the so-called Free Syrian Army”. During a subsequent meeting with Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu, Putin said that “without their participation, without the participation of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, US, Iraq, Iran and neighboring countries, it will be hard to organize such work in a proper way.”

A most significant move for the manner in which Russia imposes its new role in the Syrian conflict is the recent setting up by the Russian, Syrian and Iranian military of a Russian-Syria-Iranian “military coordination cell” in Baghdad that, according to Western intelligence sources, includes participation of low-level Russian generals and Iraqi government representatives. The “cell” is designed as a counterpart of the US-led “war room” established north of Amman for joint US-Saudi-Qatari-Israeli-Jordanian and UAE operations against the Assad regime.

When US Defense Secretary Ash Carter instructed his staff to establish a communication channel with the Kremlin to ensure the safety of US and Russian military operations and “avoid conflict in the air”, the Russian defense ministry shot back with a provocative stipulation that coordination with the US must go through Baghdad, an attempt to force Washington to accept that the two war rooms would henceforth communicate on equal terms.

Baghdad has also recently offered Moscow the Al Taqaddum Air Base at Habbaniyah, 74 km west of Baghdad, both as a way station for the Russian air corridor to Syria and as a launching-pad for bombing missions against Daesh forces and infrastructure in northern Iraq and northern Syria. The Habbaniyah air base also serves US forces operating in Iraq, an estimated 5,000.

China’s presence

The Chinese dimension makes even more complex the strategic situation surrounding the Syrian conflict, adding a new global dimension to Moscow and Tehran’s military support for Assad. This also has a detrimental effect on Israel’s strategic and military position, and strengthens Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in his determination to turn the nuclear deal concluded in July into a tool for isolating the U.S. politically, militarily and economically in the Middle East.

On September 25, the Chinese aircraft carrier Liaoning-CV-16 docked at the Syrian port of Tartus, accompanied by a guided missile cruiser. The Chinese aircraft carrier passed through the Suez Canal on September 22, one day after the summit in Moscow between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu.

The Chinese forces intent to stay in Syria for a longer period; the carrier came to Tartus without its aircraft contingent. The warplanes and helicopters should be in place on its decks by mid-November – flying in directly from China via Iran or transported by giant Russian transports from China through Iranian and Iraqi airspace. According to military intelligence sources, the Chinese will be sending out to Syria a squadron of J-15 Flying Shark fighters, some for takeoff positions on the carrier’s decks, the rest to be stationed at the Russian airbase near Latakia. The Chinese will also deploy Z-18F anti-submarine helicopters and Z-18J airborne early warning helicopters. In addition, Beijing will consign at least 1,000 marines to fight alongside their counterparts from Russia and Iran against terrorist groups.

On 2 October, China sent word to Moscow that the J-15 fighter bombers would shortly join the Russian air campaign, a development which brings to five the number or players in Russia’s military intervention in Syria: China, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Hezbollah.

Worrying similarities with the 1930s Spanish Civil War

The current situation in Syria – and especially the foreign powers’ involvement – made observers and analysts to draw parallels with the 1930s Spanish civil war. The Syrian government has the backing of Iran, Russia and China. General Franco’s Nationalists supporters were Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The Syrian rebels get help from Turkey, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. In the Spanish Civil War the Republican side had only the Communist Soviet Union as support. The anti-fascist forces were divided into Stalinist, Trotskyite and Anarchist factions, which battled each other as well as the fascists.

Frequent atrocities have marked both civil wars. The bombing of the small Basque town of Guernica in 1937 by Nazi Germany’s Luftwaffe was a particular shock because it demonstrated a new and terrifying aspect of war. Historians believe that the mass executions that took place behind Nationalist lines were organized and approved by the Nationalists’ rebel authorities, while the executions behind the Republican lines were the result of the breakdown of government and the consequent anarchy.

Another similarity is the fear that idealistic, naïve young volunteers are easily indoctrinated with dangerous ideas. In Syria the concern is that Western combatants are being trained as “jihadists” and then encouraged to return to launch attacks on home soil. There were equally plausible worries voiced during the Spanish Civil War. Young people from the West fighting the fascists joined the International Brigades, a fighting force entirely under the control of Stalin’s Soviet Union.

The most worrying aspect though, is that the Spanish Civil War turned out to have been a rehearsal for the Second World War, which was to begin just a few months later. From 1939 onwards, the great powers, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union, fought each other directly – and the German air force quickly made use of what it had learned in Spain.

During the Spanish civil war, the Republicans were helped by Russia with airplanes and tanks, while Mexico provided arms and ammunition. The Nationalists were provided by Germany with the new Messerschmitt BF109, along with German pilots with the latest tanks and bombers. Italy provided aircraft, tanks and munitions. Spain became the battleground to test the latest equipment and Germany perfected the blitzkrieg tactics so successfully used in World War II.

As in Spain, the mutation of the Syrian civil war into a “proxy war” between outside powers made the war longer, bloodier, more dangerous to the rest of the world and harder to end. Analysts assess that the proxy war in Syria seems to be in the escalation phase, as outside powers increase their efforts on the battlefield, hoping for victory for “their” side or to increase their leverage in eventual peace talks. Iran, Russia and Hezbollah have intervened on behalf of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. The US, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Turkey, France and the UK have supported opposition forces. Meanwhile, foreign jihadis continue to travel to Syria to fight as part of Daesh.

The most obvious risk is that a war fought initially through proxies leads eventually to a direct conflict. The countries that were backing opposite sides in Spain in the 1930s were fighting each other directly by the 1940s. The risk of the Syrian conflict leading to a direct clash between the Iranians and the Saudis, or even the Russians and the Americans, cannot be discounted — particularly when rival air forces are operating in proximity.

***

Most analysts agree that, even with Russia and Iran’s consistent help, the Assad regime will not be able to regain control over all the Syrian territory and will try to consolidate control over Damascus and its immediate environs, with a corridor adjacent to the Lebanese borders linking the capital with Homs and the coastal region, the ancestral land of the Alawite community.

Earlier massacres of Sunni civilians in villages inside or bordering this region were designed to cleanse a potential Alawite state entity. The current campaign by the regime and Hezbollah militia against the Sunni enclave of Zabadani close to the Lebanese border is another indication that the regime is continuing its sectarian cleansing war.

Such a de facto state could be defended by Russian and Iranian muscle for the foreseeable future, and the enclave would continue to provide Russia a port on the Mediterranean, and maintain Iran’s land access to Hezbollah in Lebanon. But, the long term survival of such an enclave, if it is not an autonomous part of a unitary federated Syrian state is very doubtful.

In these circumstances, to which one must add at least the disintegrating process in Iraq and the efforts for a Kurdish state, observers are frequently discussing the possibility of redrawn borders and new state entities in the Middle East. One century into the Sykes-Picot agreement, which drew the modern borders of the post-Ottoman Middle East, the geography and future of the British-French map is dissolving, as a sectarian inferno takes over Iraq and a war of attrition and proxy sees no end in Syria.

The geographers’ history

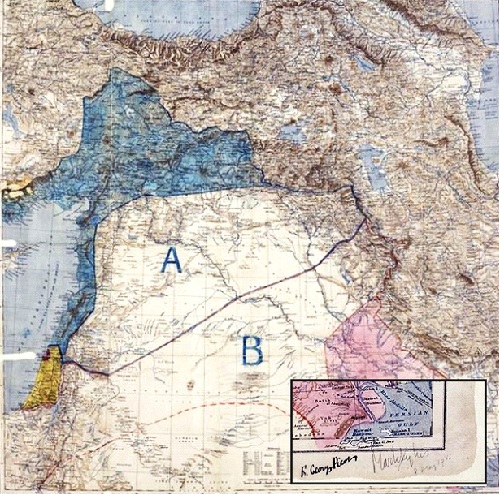

The map signed by Sykes and Picot

Source: BBC

The map of the Middle East as we know it now is largely the creation of France and Britain, the early 20th century’s colonial powers, as a result of the negotiations led by diplomats Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges Picot. Maps of the region prior to World War I have none of the countries that are at the heart of today’s war-torn Middle East. Today’s Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Yemen were created by the colonial powers after they carved up the Ottoman Empire.

While the “Sykes-Picot map” was the one that became reality at the end of World War I, it was not the first attempt of the Western powers to carve up the Turkish/Ottoman Empire.

(a) In a book published shortly before World War I and the Sykes-Picot agreement, Romanian diplomat Trandafir Djuvara counted no less than 100 projects – between 1281 and 1913 – aiming to split the Ottoman Empire and carve new borders in the Middle East, a process that became the still not solved “Middle East Question”. Starting with the Crusades and the attempts to conquer the Holy Land and followed by the projects to dismantle the Ottoman Empire and Turkey, such projects were generated, according to the Romanian diplomat, by the fact that the empire was founded on conquest and did not seek to integrate or assimilate its different populations.

Another aspect mentioned in the book was the observation of the 17th century French philosopher Montesquieu that the Turkish Empire was to resist because the European commercial powers would know their interests and will defend it.

(b) Also a century ago, the American President Woodrow Wilson sent a commission to the Middle East to explore what new nations should rise from the wreckage of the Ottoman Empire.

Under Ottoman rule, neither Syria nor Iraq existed as separate entities. Three Ottoman provinces (Baghdad, Basra and Mosul) roughly corresponded to today’s Iraq. Four others (Damascus, Beirut, Aleppo and Deir ez-Zor) included today’s Syria, Lebanon and much of Jordan and Palestine, as well as a large strip of southern Turkey. All were populated by a lot of different communities: Sunni and Shiite Arabs, Kurds, Turkomans and Christians in Iraq. In Syria, there were the same groups with also the Alawites and the Druze.

President Wilson’s commissioners, Henry King and Charles Crane, reported back their findings in August 1919. In Europe at the time, the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires was leading to the birth of new ethnic-based nation-states. But the U.S. officials advised Wilson to ignore the Middle East’s ethnic and religious differences. What is now Iraq, they suggested, should stay united because “the wisdom of a united country needs no argument in the case of Mesopotamia.” They also argued for a “greater Syria”, an area that would have included today’s Lebanon, Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian territories.

The end of Ottoman rule, King and Crane argued, “gives a great opportunity – not likely to return – to build… a Near East State on the modern basis of full religious liberty, deliberately including various religious faiths, and especially guarding the rights of minorities.” The locals, they added, “ought to do far better under a state on modern lines” than under Ottoman rule.

This was not to be the case. In Syria, the French colonial authorities, faced with a hostile Sunni majority, courted favor with the Alawites, a minority offshoot of Shiite Islam that had suffered discrimination under Ottoman rule. The French even briefly created a separate Alawite state on what is now Syria’s Mediterranean coast and heavily recruited Alawites into the new armed forces.

In Iraq, where Shiites make up the majority, the British administrators (faced with a Shiite revolt soon after their occupation began) played a similar game. The new administration disproportionately relied on the Sunni Arab minority, which had prospered under the Ottomans and now rallied around the new Sunni king of Iraq, whom Britain had imported from newly independent Hijaz, a former Ottoman province conquered by Saudi Arabia.

Colonial powers within the states created colonial administrations that educated, recruited and empowered minorities. When they left, they left the power in the hands of those minorities that became represented by dictatorships. The Assad family has ruled Syria since 1970; Saddam Hussein became president of Iraq in 1979. Notwithstanding their lofty rhetoric about a single Arab nation, both regimes turned their countries into places where the minority ruling communities (Alawites in Syria, Sunni Arabs in Iraq) were “more equal than others.” Attempts by the Sunni majority in Syria or the Shiite majority in Iraq to challenge these authoritarian orders were put down without mercy. In 1982, the Syrian regime bulldozed the largely Sunni city of Hama after an Islamist revolt, and Saddam crushed a Shiite uprising in southern Iraq after the Gulf War in 1991.

Map drawn by T. E. Lawrence

Source: BBC

c) A map developed by British archaeologist, officer, and diplomat T.E. Lawrence (well-known as “Lawrence of Arabia”) – rediscovered and presented in the early 2000s – shows that he opposed the agreement which eventually determined the borders of Iraq. He took into account local Arab sensibilities rather than the European colonial considerations that were dominant at the time.

T.E. Lawrence considered that separate governments should operate in the predominantly Kurdish and Arab areas in what is now Iraq. He presented his proposals to the Eastern Committee of the War Cabinet in November 1918, and also had the idea of separate governments for the Mesopotamian Arabs and Armenians in Syria.

Lawrence’s proposed borders – which would have replaced those drawn up in the 1916 allied agreement, which was negotiated between Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot on behalf of Britain and France – were drawn based on his talks during the Arab Revolt of 1916-18 with men from across the Middle East who were serving in the army of Britain’s Arab allies against Turkey, as well as with other British experts on the region.

The Lawrence map is considered an exercise in “what ifs”: he included a separate state for the Kurds, similar to that demanded by Iraq’s Kurds today. Lawrence groups together the people in present-day Syria, Jordan and parts of Saudi Arabia into another state based on tribal patterns and commercial routes. The map also envisions a separate state called Palestine – Lawrence knew the British were considering the creation of a homeland for the Jews. And he saw no reason to separate Iraq’s Sunnis and the Shiites – an issue that continues to divide that country today.

However, Lawrence’s suggestions came across opposition by the British administration in Mesopotamia. Although seen as they would have provided the region with a far better starting point than the crude imperial carve-up agreed by Mark Sykes and François Georges Picot, the map shows that the opinions of those who knew the region well were often ignored, as the colonial powers in London and Paris had their own agendas and did not appear to care about the facts on the ground or the people of those areas.

(d) The short-lived Treaty of Sèvres, no less than the much discussed Sykes-Picot agreement, also had consequences that can still be seen today. Sèvres internationalized Istanbul and the Bosphorus, while giving pieces of Anatolian territory to the Greeks, Kurds, Armenians, French, British, and Italians.

Within a year of signing the Treaty of Sèvres, determined to resist foreign occupation, Ottoman officers like Mustafa Kemal Atatürk reorganized the remnants of the Ottoman army and, after several years of fighting, drove out the foreign armies seeking to enforce the treaty’s terms. The result was Turkey as we recognize it today, whose borders were officially established in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.

Sèvres has been largely forgotten in the West, but it has a potent legacy in Turkey, which relates to Turkey’s sensitivity over Kurdish separatism, as well as the belief that the Armenian genocide was always an anti-Turkish conspiracy rather than a matter of historical truth. Moreover, Turkey’s foundational struggle with colonial occupation left its mark in a persistent form of anti-imperial nationalism, directed first against Britain, during the Cold War against Russia, and now, quite frequently, against the United States.

While Kurdish nationalists might claim that Turkey’s borders actually are wrong and Kurdish statelessness is due to a fatal flaw in the region’s post-Ottoman borders, they overlook the fact that when the Europeans tried to create a Kurdish state at Sèvres, many Kurds fought alongside Atatürk to upend the treaty.

The Kurdish state envisioned in the Sèvres Treaty would have been under British control. While this appealed to some Kurdish nationalists, others found this form of British-dominated “independence” problematic. So they joined up to fight with the Turkish national movement. Particularly among religious Kurds, continued Turkish or Ottoman rule seemed preferable to Christian colonization. Other Kurds, for more practical reasons, worried that once in charge the British would inevitably support recently dispossessed Armenians seeking to return to the region.

Many Turkish nationalists remain frightened by the way their state was destroyed by Sèvres, while many Kurdish nationalists still imagine the state they might have achieved.

In the case of the Sykes-Picot agreement – the one that materialized into the current Middle East borders – most historians and analysts agree that it resulted in three problems that came to influence the regional geo-political situation.

First, not only it was secret without any Arabic knowledge, but it also negated the main promise that Britain had made to the Arabs in the 1910s – that if they rebelled against the Ottomans, the fall of that empire would bring them independence. When that independence did not materialize after World War I, and as these colonial powers, in the 1920s, 30s and 40s, continued to exert influence over the Arab world, the thrust of Arab politics shifted from building liberal constitutional governance systems to assertive nationalism whose main objective was getting rid of the colonialists and the ruling systems that worked with them. This was a key factor behind the rise of the militarist regimes that had come to dominate many Arab countries from the 1950s until the 2011 Arab uprisings.

The second problem lays in the tendency to draw straight lines and divide the Levant on a sectarian basis: Lebanon was envisioned as a haven for Christians (especially Maronites) and Druze; Palestine with a sizable Jewish community; the Bekaa valley, on the border between the two countries, effectively left to Shiite Muslims; Syria with the region’s largest sectarian demographic, Sunni Muslims. However, the thinking behind Sykes-Picot did not translate into practice and the newly created borders did not correspond to the actual sectarian, tribal, or ethnic distinctions on the ground.

These differences were buried, first under the Arabs’ struggle to eject the European powers, and later by the sweeping wave of Arab nationalism. However, the tensions and aspirations persisted. When cracks started to appear in these countries – first by the gradual disappearance of these strong men, later by several Arab republics gradually becoming hereditary fiefdoms controlled by small groups of economic interests, and most recently after the 2011 uprisings – the old frictions, frustrations, and hopes that had been concealed for decades, came to the fore.

The third problem was that the state system that was created after the World War One has exacerbated the Arabs’ failure to address a crucial dilemma – the identity struggle between, on one hand nationalism and secularism, and on the other, Islamism (and in some cases Christianism). Also, for the past four decades, the Arab world has lacked any national project or serious attempt at confronting the contradictions in its social fabric.

That state structure was poised for explosion, and the changing demographics proved to be the trigger. Over the past four decades, the Arab world has doubled its population, to over 330 million people and two-thirds of them are under 35 years old. At core, the wave of Arab uprisings that started in 2011 is this generation’s attempt at changing the consequences of the state order that began in the aftermath of World War One. This currently unfolding transformation entails the promise of a new generation searching for a better future, and the peril of a wave of chaos that could engulf the region for several years.

The post Sykes-Picot order: new maps for old problems

The breakup of the Syrian and the Iraqi states, as well as the ascension of Daesh are seen as symptoms of a soon-to-come post-Sykes-Picot configuration. While the international community still emphasizes publicly the unity of Iraq and Syria, in reality everyone is quickly adjusting to the new order. Arming of Kurdish groups, investing in Shiite, Sunni and Druze militias, is happening faster than any political solution. From Washington and the Western point of view, the nation states in Baghdad and Damascus are breaking up and it is too costly to save them.

The Middle East has been in a state of chaos for years and many analysts point out that Western foreign policy has directly caused or exacerbated much of this chaos and has contributed to a growing trend of instability. Some even question if this instability is a result of a calculated strategy by the West to create chaos, balkanize nations and increase sectarian tensions in the region.

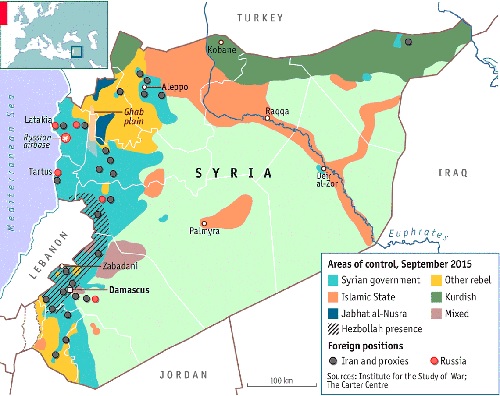

Dividing Syria

Syria situation map, September 2015

Source: The Economist

While the idea of dividing Syria was launched since the Syrian uprising in 2011, the concept is not easy and governments still oppose it given the repercussions for the countries in the region. However, there are many indications that a partition of Syria is the most likely future scenario. Iran and Hezbollah have withdrawn their forces from large parts of the north and south since the beginning of the year. They want to focus on defending the core region controlled by Assad, which they can hold, the densely populated strip from Damascus to Latakia.

If Assad escapes Damascus to Latakia or to Qardaha and decides to build his republic there, it will not guarantee international recognition. Moreover, it would trigger a civil war, which will follow Assad wherever he goes in Syria. Assad will be the target of all angry Syrians and he will not be capable of providing permanent international protection for his new state. The Alawites themselves will consider Assad a burden and will blame him for their disaster (most of the Alawite elites left the country to Europe and Gulf countries).

The gradual dissolution of Syria makes it difficult to find a solution for the entire country. Two other parties have already taken control of large portions of the country. In the north, troops with the Kurdish YPG (People’s Protection Units, the main armed service of the Kurdish Supreme Committee, the government of Syrian Kurdistan), the Syrian branch of the PKK, control the three traditionally Kurdish areas along the Turkish border. And even they consistently deny wanting to establish a Kurdish state, this is precisely what Western intelligence officials believe they intend to do. This is why the Turkish government is doing everything in its power to prevent the YPG from capturing more territory. Hezbollah, in turn, has captured a broad strip of land along the Lebanese border in a move that could disrupt the country’s delicate confessional balance.

A partition of Syria would probably be the biggest favor for Daesh. A Russian-Iranian protectorate in the west would stand in the way of any unification of the entire country, and it would mean abandoning the rest of the country to the “Caliph” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who knows that the Syrian rebels alone cannot defeat Daesh.

Iraq: towards three states

The objective of dividing Iraq into three different state entities has been discussed as far back as 1982, when Israeli journalist Oded Yinon, wrote an article which was published in a journal of the World Zionist Organization, titled: “A Strategy for Israel in the Nineteen Eighties”. Yinon discusses the plan for a Greater Israel and pinpoints Iraq in particular as the major obstacle in the Middle East which threatens Israel’s expansion.

In the case of Iraq, fragmenting it into three separate regions has been talked about in the U.S. since the 2003 invasion of the country, although NATO member Turkey has vocally opposed the creation of a Kurdish state in the North. Also in 2003, the President Emeritus of the CFR, Leslie Gelb, argued in a 2003 article for the ‘New York Times’ that the most feasible outcome in Iraq would be a “three-state solution: Kurds in the north, Sunnis in the center and Shiites in the south.”

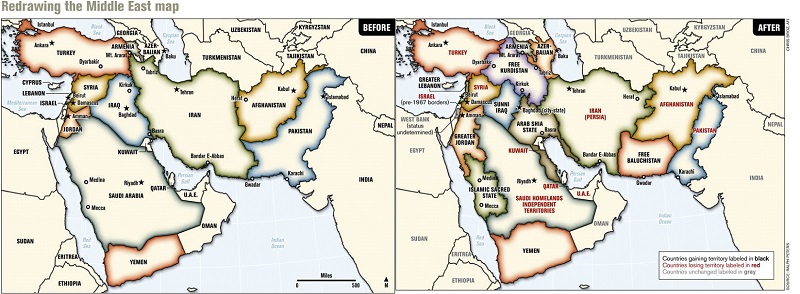

In 2006, a potential map of a future Middle East was released by Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Peters which depicted Iraq divided into three regions: a Sunni Iraq to the West, an Arab Shiite State in the East and a Free Kurdistan in the North.

Maps drawn by Ralph Peters and published in the American Armed Forces Journal in June 2006

Jeffrey Goldberg map

The Atlantic, January 2008

A somehow different “new Middle East” was imagined in 2007 by U.S. analyst Jeffrey Goldberg, who “predicted” the break-up of Sudan into two countries (calling what is today known as South Sudan “New Sudan”). It also included a “Hezbollahstan” in part of Lebanon, which nowadays exists de facto. North of Hezbollahstan is “The Alawite Republic,” along what is now Syria’s Mediterranean coast. Syria also loses territory to a “Druzistan” that touches the northern border of “Greater Jordan.” Iraq is divided into three states, and the Kurdish state even takes in parts of Turkish-ruled Kurdish territory. One addition to the map – the Bedouin Autonomous Zone – is what could have developed in the Sinai Peninsula before the Egyptian military coup and the Egyptian military’s re-energized plan to seize Sinai back from jihadist tribesmen.

“Balkanization” strategies

Several articles and publications revealed that at least some Western strategists contemplate the idea of balkanizing the region into feuding rump states, micro-states and mini-states, which will be so weak and busy fighting each other that they will be unable to unify against foreign powers and multinational corporations. They assume that after a prolonged period of destruction and chaos in the region, the people of the Middle East may be so weary that they will accept a Western imposed order as a means of ending the fighting, even though the very same Western forces have been responsible for creating much of the intolerable chaos.

An example of such a strategy was published by British-American historian Bernard Lewis in the autumn 1992 issue of ‘Foreign Affairs’, under the title Rethinking the Middle East. It envisaged the potential of the region’s so-called “Lebanon-ization”, since most of the states of the Middle East are of recent and artificial construction and are vulnerable to such a process. If the central power is sufficiently weakened, there is no real civil society to hold the polity together, no real sense of common national identity or overriding allegiance to the nation state. “The state then disintegrates – as happened in Lebanon – into a chaos of squabbling, feuding, fighting sects, tribes, regions and parties. If things go badly and central governments falter and collapse, the same could happen, not only in the countries of the existing Middle East, but also in the newly independent Soviet republics, where the artificial frontiers drawn by the former imperial masters left each republic with a mosaic of minorities and claims of one sort or another on or by its neighbors.”

Former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger also mentioned in 2013, speaking at the Ford School, his desire to see Syria balkanized into “more or less autonomous regions”, in addition to comparing the region to the Thirty Years War in Europe: “There are three possible outcomes. An Assad victory. A Sunni victory. Or an outcome in which the various nationalities agree to co-exist together but in more or less autonomous regions, so that they can’t oppress each other. That’s the outcome I would prefer to see. But that’s not the popular view…. I also think Assad ought to go, but I don’t think it’s the key. The key is; it’s like Europe after the Thirty Years War, when the various Christian groups had been killing each other until they finally decided that they had to live together but in separate units.”

Such an unit was mentioned in a 2012 Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) report, formerly classified and recently released, which reveals that the powers supporting the Syrian opposition – “Western countries, the Gulf states and Turkey” – wanted to create a Salafist principality in Eastern Syria in order to isolate the Syrian regime which is considered the strategic depth of the Shiite expansion (Iraq and Iran). The report also mentioned the possibility that what was then the “The Islamic State of Iraq” (Daesh) could “declare an Islamic State in Iraq and Syria”.

The pattern of balkanization is also to be seen in Libya. Following the NATO’s 2011 war, the country has essentially been split into three parts, with Cyrenaica comprising the East of the country, and the West split into Tripolitania in the Northwest and Fezzan in the Southwest. Libya is now a failed state, lacking a central government and stricken by tribal warfare.

An “EU-model”

Some Western strategists are also proposing a centralized, sovereignty-usurping union, in a classic deployment of the “order out of chaos” doctrine. As ‘The New American’ recently reported, Mohamed Ed Husain, an Adjunct Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies at the Council for Foreign Relations (CFR), compared today’s Middle East to Europe before the EU was created, and he asserted that the only solution to the ongoing violence is the creation of a “Middle Eastern Union”, which would put populations ranging from Turkey and Jordan to Libya and Egypt under a single authority. The idea was exposed in an article published in the ‘Financial Times’ and on the CFR website: “Just as a warring [European] continent found peace through unity by creating what became the EU, Arabs, Turks, Kurds and other groups in the region could find relative peace in ever closer union,” he claimed. “After all, most of its problems – terrorism, poverty, unemployment, sectarianism, refugee crises, water shortages – require regional answers. No country can solve its problems on its own.”

The idea of an EU-style governing body over the Middle East is not a new concept. In 2008, in an address to the US think tank the “Institute of Peace”, the Iraqi government called for an EU-style trading bloc in the Middle East that would encompass Saudi Arabia, Iran, Kuwait, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Turkey and later perhaps the Gulf states. In 2011, the then president of Turkey, Abdullah Gül, also called for an EU-style regime to rule the Middle East. Speaking in the United Kingdom, Gül claimed “an efficient regional economic cooperation and integration mechanism” was needed for the region. “We all saw the role played by the European Union in facilitating the democratic transition in central and Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall,” he claimed. Various Middle Eastern leaders also have echoed the calls for a regional regime: the kings of Saudi Arabia and Jordan, for example.

Other groups working toward such a union are to be found across the region, such as the “Middle East Union Congress” which seeks a “Middle East that is empowered, free, and governs for all it’s (sic) peoples at the highest level of being in a new world where the Middle East Union is an important integral part of a greater global community that pledges its allegiance to the earth and every human on it,” as it declares on its website. By 2050, the new Congress aims to bring some 800 million people from Pakistan in Asia to Morocco in Northwest Africa under a single regime with a single euro-style currency. It also wants to create a new capital city for the union named after Nelson Mandela, whom it described as “the 20th century’s greatest global citizen.”

Such a project would also advance the longtime establishment goal of setting up regional regimes on the path to a more formal system of “global governance.” In the Middle East, numerous similar efforts such as the Gulf Cooperation Council and the Arab League have been making progress, too. A true “union” to rule over the broader Middle East and North Africa, would represent a major step forward in the ongoing regionalization of power around the world.

After redrawing

The different variations of the re-drawn Middle East borders all include a Kurdish state. The Kurds, who live scattered across Iraq, Turkey, Syria and Iran, have already enjoyed decades of virtual independence under an autonomous government in northern Iraq (the mountainous part of what was once the Ottoman province of Mosul) and they have established three autonomous “cantons” in northern Syria. Beyond Kurdistan, however, the case for separate new nations becomes much less clear, despite the ethnic and sectarian horrors that torment the region today.

While artificially created, the post-Ottoman states have proven resilient. Lebanon, a country of some 18 religious communities, survived a bloody, multi-sided civil war from 1975 to 1990 and has repeatedly defied predictions of its imminent demise. It remains an island of relative stability amid the current regional upheaval, even as it is being overwhelmed by more than a million Syrian refugees. Also, despite the ethnic cleansing of recent years, Sunnis and Shiites still live together in many parts of Iraq, including Baghdad, and a great many Syrian Sunnis would still rather live in cities controlled by the Assad regime than in war-ravaged areas under rebel sway.

The only recent partition of an Arab country – the split of Sudan into the Arab north and the new, largely non-Arab Republic of South Sudan in 2011 – doesn’t provide an encouraging precedent for would-be makers of new borders. South Sudan quickly slid into a civil war of its own that has killed tens of thousands and uprooted two million people.

There’s also the case of Somalia, which has been through a bitter experience ever since the regime collapsed following the death of President Siad Barre. Somalia has been in chaos for more than 20 years now, and it’s divided into at least three statelets, including Somaliland, which declared its independence two decades ago and it has its own government, police and currency; however, no one recognizes it.

According to researchers of the Middle East question, drawing new borders might not be as efficient as forging a new bottom-up social compact within the region’s existing borders. The real problem in the Middle East is a collapse not of the borders but of what was happening inside the borders: governments that did not have a lot of legitimacy to start with and did not earn legitimacy with their people.

Always between the global superpowers

According to many observers, the Obama Administration’s overall aimlessness in the Middle East, its lack of resolve in dealing with Syria’s wars – that are threatening the whole Eastern Mediterranean region – and its unwillingness to challenge Iran’s destabilizing activities in Syria and Iraq, as well as its inability to pursue a comprehensive regional strategy against Daesh, gave Putin a historic opportunity to re-assert Russia’s influence in the region.

A closer analysis reveals that, if Russia is poised to return to the Middle East, from which it was ejected with the collapse of the USSR, the United States seems to be telling Russia to go ahead, because it is unwilling to engage – though it is not yet ready to fully retreat.

According to many observers, rather than a bid to end the war to the Syrian leader’s advantage, Russia’s move may be aimed at preventing his regime’s collapse. At the same time, say diplomats and analysts, Mr. Putin wants to repair ties with the West, and to build leverage over vexed issues such as Ukraine, by posing as a potential partner in the fight against Daesh.

The cold war “battle” for Syria

It’s not the first time that Syria was the object of a confrontation between the two superpowers. In the 1950s, regional and international powers were trying to move Damascus in one direction or another in the midst of two overlapping cold wars, the one between Arab states, and the one between global superpowers. Through bribery, propaganda, political pressure, and covert (and sometimes overt) military action, these external players attempted to manipulate a fractured Syrian polity for the sake of strategic self-interest. The culmination of this struggle for Syria occurred during and immediately after the 1957 American-Syrian crisis. In August of that year, Syrian intelligence uncovered a covert U.S. plot to overthrow a government in Damascus that the Eisenhower administration believed was perilously close to becoming a Soviet client-state in the heart of the Middle East.

This episode brought together (and out in the open) the matrix of domestic, regional, and international forces at work in Syria in that period: domestic political rivalries; the growth of Arab nationalism led by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser; the struggle for Syria between Iraq, Egypt, and the Saudis; the intensifying U.S.-Soviet Cold War; and an increasingly nervous Israel. The crisis improved the positioning in Syria of Washington’s adversaries in the Middle East, Egypt and the Soviet Union.

During this crisis, both Egypt and the Soviet Union claimed they were trying to “save” Syria from the pernicious activities of the West. But as events unfolded, it became clear that their objectives diverged. Egypt’s Nasser had worked long and hard to keep Syria from joining pro-West defense schemes in the region (such as the Baghdad Pact), thus preventing his country’s isolation at the hands of his regional rival at the time, Iraq. He wasn’t about to lose the assets he had cultivated in Syria to another country – even the Soviet Union, with which he had had a strategic but uneasy partnership. In the end, Egypt “won” Syria by taking direct action: Nasser’s hold on Syria was so strong that Damascus came under his leadership to form a united country: the United Arab Republic (UAR). Certainly Moscow had improved its position in Syria, but Nasser’s Egypt had many more entry points into the country that gave it a distinct advantage over a relatively distant superpower.

However, Nasser was soon to learn the hard way that an ownership stake in Syria can be a disaster. After he “saved” Syria, Nasser shackled his country to the Syrian matrix, which compelled him to reluctantly agree to the UAR – a union that quickly failed, taking the luster off Nasser’s glow and deepening divisions in the Arab world. In hindsight, it may have been the beginning of the end of Nasserism, the immensely popular pan-Arabist movement that gained center stage following Egypt’s survival against the British-French-Israeli tripartite invasion in the 1956 Suez Crisis, which also transformed Nasser into a regional hero. The problems Egypt experienced in Syria before and after the breakup of the UAR ultimately led to the disastrous 1967 Six-Day War.

After the 1957 debacle in Syria, the United States could do little but watch and accept the realities of the situation and the limits of U.S. power. Indeed, following the Iraqi revolution in July 1958 that swept aside the pro-Western monarchy, the three most important Arab countries (Egypt, Syria, and Iraq) appeared to be aligned with Moscow. But in Washington, while facing criticism for appearing to allow Soviet influence in the Middle East to expand, Eisenhower administration officials seemed happy to let the Soviets try to dig out of the hole they had created for themselves.

Russia’s comeback

By boosting its military presence in Syria, Russia has created irreversible facts on the ground and demonstrated that it reserves the right to be involved in resolving any conflict or crisis, wherever in the world it may occur. The Kremlin sees this indispensability – together with its sphere of influence, which is at the root of the Ukraine crisis – as a key ingredient that defines Russia as a global power.

The forces Mr. Putin has just deployed to Syria are impressive, veteran special operators backed by a wing of fighters and ground attack jets, backed by air defense units, which indicate that the Kremlin’s true intent in Syria has little to do with the stated aim of fighting terrorism and is really about propping up Russia’s longtime client in Damascus.

In spite of the current propaganda, Russia seems to coordinate its military efforts in Syria with Israel and the U.S. According to military intelligence sources, there is an informal agreement with the Israelis and Americans not to target regions near the Golan Heights and the Druze communities, which will be subject of later negotiations. The same sources mention that the Russian operations are in agreement with the American Presidency, although there is no consensus in Washington on the Syrian question.

Some Russian officials also acknowledge privately that Assad’s days as ruler of anything resembling a united Syria are likely numbered. But Putin wants to avoid the sort of uncontrolled chaos that followed the fall of Saddam Hussein in Iraq and Muammar al-Qaddafi in Libya. Instead, he wants to ensure that a post-Assad government respects Russian equities, notably, maintenance of the Russian naval base at Tartus, which is critical to Moscow’s efforts to project power into the Mediterranean as the United States pulls back from the region.

A more consistent presence in the MENA region would compensate for Moscow the economic difficulties generated by the West’s sanctions following the Ukraine crisis, but more than that, it would help to compensate the Russian failure to bring the conflict to the planned solution – the “finlandization” of Ukraine into a federation that would follow the Kremlin orders in the national security matters. The Syrian conflict and Russia’s involvement may help Moscow not only to distract the West’s attention from Ukraine, but also to use Syria as a “bargaining chip” to negotiate a solution in Ukraine. Thus, Russia might accept to retreat from the Donbas region in exchange for constitutional changes in Ukraine and oblige the US to acknowledge the Russian security interests in Europe.

It is also significant to remember that Putin’s main inspiration on Middle East affairs comes from the late Yevgeny Primakov, former Russian prime minister and a long-time pillar of KGB policies in the region. Primakov, who died earlier this year, played an important role in securing tight links between the Russian and Syrian intelligence services. In his book Russia and the Arabs, he theorized about how Russia’s role in the region might reflect its global status and its capacity to counter America’s influence. Primakov also set the Russian tone of denouncing the 2011 Arab spring as a western plot aimed at regime change that must be opposed.

The West’s shifting

Frustration with Syria and alarm in Europe at the surge in refugees pounding at its gates, have produced an increased willingness among Western diplomats to soften their hostility to Mr. Assad’s regime. Even John Kerry, America’s secretary of state, said recently that, in a negotiated solution, the Syrian leader’s departure need not necessarily take place “on day one or month one or whatever”.

Russia’s embrace of the Syrian leader has accelerated this shift. Senior European diplomats, including Germany’s foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, welcome Russian intervention. Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu paid a visit to Moscow, accompanied by his defense chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Gadi Eizenkot, and the head of military intelligence, Maj. Gen. Herzl Halevi, to seal protocols to ensure that there will be no unintended clashes between Israeli and Russian forces. Even Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, flew to Moscow on September 23rd for the inauguration of a new mosque, claimed as the largest in Europe.

The shifting position is also to be seen among the European Union leaders, with European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker recently declaring that “Russia must be treated decently” and that Europe cannot let its “relationship with Russia be dictated by Washington.”

The pro-Moscow tilt has also triggered a shift to more pragmatic politics among rebel groups on the ground. After months of complex negotiations involving Iran and one rebel coalition, agreement has been reached for a ceasefire and population swap in two besieged zones. Some 29 rebel factions also signed an agreement in Istanbul in September endorsing a UN plan to set up four parallel working groups to seek practical solutions to Syria’s myriad woes.

Analysts also explain the recent developments in the Middle East as being favored by the vacuum created by Barack Obama’s attempt to stand back from the wars of the Muslim world. America’s president told the UN General Assembly that his country had learned it “cannot by itself impose stability on a foreign land”; others, Iran and Russia included, should help in Syria. Mr. Obama is not entirely wrong. But his proposition hides many dangers: that America throws up its hands; that regional powers, sensing American disengagement, will be sucked into a free-for-all; and that Russia’s intervention will make a bloody war bloodier still. While American intervention can indeed make a bad situation worse, America’s absence can make things even worse and, at some point, extremism will force the superpower to intervene anyway.

The risk of a Damascus – Baghdad – Tehran axis

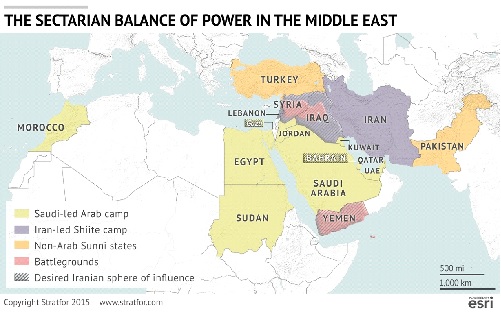

The region’s sectarian balance as assessed by Stratfor

While the two superpowers are, in reality, less antagonistic about the Middle East than it looks in the official propaganda – with the Pentagon announcing talks with Russia’s military on pilot safety as the US and the Kremlin seek to avoid accidental clashes as they carry out separate bombing campaigns – any kind of settlement will require the contribution of the regional actors.

For Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, Moscow has worrying intentions, including supporting Damascus and potentially selling the S-300 weapon system to Iran, not to mention its free-riding behavior in global oil markets. Russia’s deployment of forces reminds Saudi Arabia and the Gulf nations that Moscow is an important international power that cannot be ignored, but also the dangers that result from Kremlin’s alliance with Iran.

Russia’s military intervention in support of President Bashar al-Assad has dismayed Gulf Arab enemies of the Syrian leader who say it will prolong the war and keep Syria firmly in the orbit of their regional rival Iran. Publicly at least, the Gulf Arabs are sticking to their line that Assad cannot survive despite Russia’s military support. While Riyadh prefers a political solution, its foreign minister al-Jubeir said, “the military choice is still available, as the Syrian opposition is still fighting the regime with more efficiency with the passing of time”.

Other Gulf Arab officials say the Russian intervention was made possible only by what they see as a lack of U.S. engagement on Syria. There is also the recognition of Putin’s consistent loyalty to his ally, a quality Gulf Arabs say their U.S. friend lacks.

Sami Al-Faraj, a Kuwaiti security adviser to the Gulf Cooperation Council, recently told Reuters that the Russian intervention meant Syria would be partitioned between a coastal strip held by Assad – who is from the Alawite minority, an offshoot of Shiite Islam – and a Sunni Muslim majority hinterland, with Iran a major beneficiary. “The GCC understands that a new Syrian entity carved out under Assad means preserving Iranian interests, which is to have a front in the Mediterranean,” he said. “The Iranians have chosen the right great power to be with – the Russians.”

Another worrying development for the Saudi-led group is the extent to which the Iranian regime, its Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Hezbollah benefit from the so-called “Shiafication” of the Iraqi military and security forces. Iran’s growing influence in Iraq makes more and more possible a “Shiite axis” Damascus – Baghdad – Tehran, directly challenging Saudi Arabia’s strategic interests.

The recent joining by Iraq of the “military cooperation cell” with Russia, Iran and Syria, as well as the declarations of Hakim al-Zamili, the head of Iraqi parliament’s defense and security committee, that Iraq may request Russian air strikes against Daesh on its soil are the most recent events to confirm the development of such an axis.

In the case of Israel, while it has never had an interest in the complete collapse of the Assad regime, the civil war surprised Israeli intelligence and policy makers, particularly the extent of the Hezbollah and Iranian involvement, that might materialize into two essential dangers: the transfer of dangerous weapons from the Syrian army to the hands of Hezbollah; and a Hezbollah-Iranian military and terrorist presence in the Syrian side of the Golan Heights.

Israel problem is that in keeping Assad in office, Putin is becoming an ever more important ally of Iran and Hezbollah, who have been fighting for Assad for three years now. Israel fears the Kremlin’s buildup could further escalate the Syrian civil war and embolden Iran and Hezbollah, its two greatest foes in the Middle East, both of which have joined Moscow in supporting Damascus.

Israel’s actual policy, never pronounced, is similar to its position during most of the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s: it secretly wishes success for both sides in killing its enemy. No possible outcome in the Syrian crisis is good for Israel: an Assad victory means a triumph for Iran and Hezbollah, while a victory for either Daesh or the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front will leave Damascus in the hands of a radical and extremely hostile regime. The best scenario for Netanyahu would be an ongoing war of attrition, which keeps Israel’s enemies busy fighting each other instead of uniting against it.

The refugee crisis: “collateral effect” in the Middle East, considerable damage for the Schengen Agreement

Since the conflict in Syria began in 2011, it has produced more than four million refugees, and approximately eight million internally displaced people. More than 200,000 people have died. More than half of the 22 million people who were living in Syria in 2011 are either dead or displaced.

The contemporary Middle East humanitarian disaster resembles, in its degree of suffering and international indifference, the one that occurred during and following the First World War. When British power in Palestine collapsed, 750,000 Arab Palestinian refugees were created. Their existence today and that of their descendants remains a humanitarian scandal.

In this context, historians also evoked the refugee wave triggered by the Armenian Genocide in Turkey, during which more than 1.5 million Armenians were killed. The genocide was preceded by the Hamidian massacres of 1894-95, which were ordered by Sultan Abdülhamid II and which caused between 80,000 and 300,000 victims, and continued on a huge scale with the massacres perpetrated between 1915 and 1923, by the «Special Organization» of the Union and Progress Committee (UPC), until the election of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as President of the Republic (1923), which caused between 1,200,000 and 1,500,000 deaths. By the end of 1922, about three millions Christians had been killed in the decade-long religious cleansing that operated essentially under two Turkish governments.

Armenians who escaped or survived the massacres were scattered across the Middle East and Russia. Many of the surviving refugees eventually migrated to Western Europe or North America. The large Armenian diasporas, from the United States to Uruguay, from France to Syria, are a direct consequence of 1915. Today, there are four times as many Armenians living outside the country as in it.

After the war, U.S. and other Christian nations decided that survivors of the 1915 Armenian genocide should go back to what had been their homes in “Western Armenia” (Ottoman Anatolia). And many hundreds of thousands of Armenians lingered on the edge of Turkey in the hope that the victors of the First World War would return them to lands no longer controlled by their Ottoman Turkish killers.

The killing of Armenians in 1915 was the first attempt to wipe out an indigenous Christian population in its ancestral homeland, and similar attempts are being made across the entire Middle East.

Now, in the break-up of the present-day Middle East, Christian refugees from Iraq and Syria and Egypt – like those Armenians who headed for America and Europe in the 1920s – have generally been received by Christian countries. But most of the refugees today are Muslims fleeing Muslims and they are not receiving the same generosity.

Turkey’s role in the refugee crisis

According to many sources, there is a direct relationship between the flow of refugees and the policies, both overt and covert, of the countries participating either directly or indirectly in these wars. Among others, accusations were directed against the facilitation of refugee travel by the Turkish government despite the reports of Daesh, the al-Qaeda groups, and other criminal organizations engaging in human trafficking in Syria and Libya specifically.

With respect to Syria, Turkish intelligence is accused of being involved with jihadis of al-Nusra and Daesh in smuggling both fighters and weapons into Syria in the ongoing attempt to implement regime change against the Syrian government.

The Turkish daily Cumhuriyet recently mentioned that a group of jihadis were brought to the Turkish border town of Reyhanli on January 9, 2014 from Atme refugee camp in Syria in a clandestine operation. From there, they were smuggled into Tal Abyad, a border town used by Daesh as a gateway from Turkey, on two buses rented by the MIT (Turkish intelligence), which it said were stopped by police a day after the operation following a tip-off that they were smuggling drugs into Syria. It was revealed that the buses had been used to smuggle jihadis after investigators found bullets, weapons and ammunition abandoned in the buses. The drivers of the buses, who were briefly arrested, said in their testimony they were told that they were carrying Syrian refugees and the vehicles were rented by the MIT. As the bus drivers’ testimony indicated, they were told by Turkish authorities that they were carrying Syrian refugees. It seems then that Turkish intelligence openly facilitates the transit of refugees throughout Turkey, and has a direct chain of custody over their movements.

Some analysts estimate that the Russian-coordinated operations in Syria, which aim primarily to reinstate the Assad regime, would target the al-Nusra Front (supported mainly by Qatar and Turkey) in the Idlib region, which may be taken under control in about three weeks after the operation starts. Consequently, members of al-Nusra and other terrorist groups will have no choice but to flee to Turkey, which increases the risk of infiltrating the refugee groups coming to Europe.

An ambiguous position in Europe

For historian Bat Ye’Or, the current Muslim migration wave in Europe is also a result of the complex process that was started in the mid ‘970s with the French and German initiatives to create a European Coordination Committee of the Friendship Associations with the Arab world that took the name of “Eurabia”.

The Eurabia committee was the instrument for implementing a strategy developed in the ‘960s by France and Germany to create a Mediterranean economic, cultural and political community. It resulted in the creation of European Union institutions that cooperated with the Arab League and the Islamic Cooperation Organization. In exchange, the Arab League asked for support for the Palestine cause and an anti-Israel policy. According to Eurabia intellectuals, which were active in Western Europe for almost 50 years, with the “Mediterranean civilization”, Europe would benefit from the oil resources, would find its old roots in the Islamic civilization and would transform the Mediterranean in an Euro-Arab lake, from which the US and Israel would have been driven out.

The current migratory wave is to be linked to this strategy of the European Council and Commission, which explains, for Bat Ye’Or, the favorable reaction of the European governments (with the exception of the new EU members). It is seen as accelerating the process of “Palestinization” (de-Christianization) and islamization (demographic, cultural and political) of the European societies.

A price to pay to Turkey

Turkey, which is the main source of Syrians trying to move to Germany, was recognized as the lynchpin of any strategy for containing the crisis and it emerged that Ankara was demanding a high price for its cooperation. Ahmet Davutoğlu, the Turkish prime minister, wrote to the EU leaders demanding bold concessions from the Europeans as the price for Turkey’s possible cooperation. He proposed that EU and the U.S. support a buffer and no-fly zone in northern Syria by the Turkish border, measuring 80 km by 40 km. This, in fact, would affect the Kurdish militias fighting Daesh in northern Syria and would also enable Ankara to start repatriating some of the estimated 2 million Syrian refugees it is hosting. The militias are allied with the Kurdistan workers’ party (PKK) guerrillas, which are at war with the Turkish state for most of the past 30 years.

The EU offered new incentives to Turkey – including financial aid (up to 1 billion Euros) and easing of visa restrictions – for help to solve the migrant crisis. In exchange, Turkey would undertake various measures including implementing asylum procedures and giving priority to “the opening of the six refugee reception centers built with the EU co-funding”. However, Brussels’ offer did not address some the demands made by President Recep Tayyp Erdoğan during his meetings in Brussels in October, especially for the creation of a safe haven and no-fly zone around Syria’s northern border and for Turkey’s EU membership process to move ahead more quickly.

The Schengen Agreement: an uncertain future

Migration wave to Europe

Source: BBC

The last October 2015 emergency Brussels summit on the refugee crisis failed to come up with common policies amid signs they were unable to contain and manage the migration. It decided only to throw money at aid agencies and transit countries hosting millions of Syrian refugees and to step up the identification and finger-printing of refugees in Italy and Greece by November. Calls for European forces to take control of Greece’s borders – the main entry point to the European Union from the Middle East – fell on closed ears. The summit’s chairman delivered coded criticism of the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, and of the European commission while warning that the refugee crisis would get much worse before it might get better.

The combination of a rising number of asylum seekers, stronger nationalist parties and fragile economic recovery are leading governments and political groups across Europe to request the redesign, and in some cases the abolishment, of the Schengen Agreement.

The Schengen Agreement, signed by France, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg in 1985, envisioned a system in which people and goods could move from one country to another without barriers, and since its implementation in 1995, it eliminated border controls between its signatories and created a common visa policy for 26 countries.

The treaty was a key step in the creation of a federal Europe. By eliminating border controls, member states gave up a basic element of national sovereignty. The agreement also required a significant degree of trust among its signatories, because once people have entered a Schengen country, they can move freely across most of Europe without facing any additional controls.

On the one hand, countries in northern Europe criticize countries on the Mediterranean for their lack of effective border controls and for their failure to fingerprint many of the asylum seekers that reach EU shores. On the other hand, countries in southern Europe criticize their northern peers for their lack of solidarity. Italy and Greece have repeatedly demanded more resources to patrol the Mediterranean and rescue immigrants, more funds to shelter asylum seekers and the introduction of immigration quotas in the European Union. Central and Eastern European countries, which think asylum seekers should be distributed on a voluntary basis, rejected the idea of quotas.

The migration crisis has also led to greater friction between Schengen members and their non-Schengen neighbors. The recent dispute between France and the United Kingdom (which is not a member of the Schengen zone) over immigrants trying to cross the English Channel at Calais was perhaps the most visible example of the growing tension, but the situation also led Hungary to build a fence at its border with Serbia and issue threats to militarize the border.

In the current form, the Schengen Agreement makes it possible for illegal immigrants to move freely among member states and several member states have expressed concern that some of migrants arriving in Europe could be terrorists.

The rise of nationalist parties is also a threat to the Schengen Agreement. In Finland, a nationalist party is already a member of the government coalition, and Euroskeptic and anti-immigration parties are influential in countries such as Denmark, Sweden and Hungary. In France, most opinion polls show that the Euroskeptic National Front will make it to the second round of the presidential election in 2017. All of these parties believe that national immigration laws should be toughened and the Schengen Agreement should be revised, if not abolished.

This is not the first time that the Schengen agreement has appeared to be in danger of fraying. In 2011, fearing an influx of North African refugees, Italy and France pushed for a review of the agreement. Earlier this year the Dutch prime minister threatened Greece with expulsion if it allowed migrants free passage to the rest of Europe. Neither eventuality came to pass.

The future of Schengen

The European Union also needs to come up with a new immigration policy and until the end of 2015 EU members will try to reform the bloc’s immigration rules. The Schengen Agreement will probably be reformed before the end of the decade to make it easier for countries to reintroduce border controls.

The first step in this direction happened in 2013, when signatory members agreed that border controls could be temporarily reintroduced under extraordinary circumstances (such as a serious threat to national security).

Germany that only a few months ago was reluctant to change the Dublin regulations (according to which asylum requests should be processed in the country of a migrant’s first entry) is now leading the push for a change. Berlin’s proposals include the creation of a common list of countries considered safe, which means their nationals, in principle, should not be allowed to request asylum in the European Union. This list would largely include countries in the Western Balkans, such as Albania and Macedonia, which are not experiencing a civil war or any particularly serious humanitarian crisis that would justify a request for asylum. Germany’s second proposal is the allocation of more funds and staff to centers in Greece and Italy to identify immigrants and process their applications. Finally, Berlin will also push for a proportional distribution of migrants across the European Union.

However, each of these points is highly contentious. Asylum requests are a case-by-case issue, and it often takes a long time for authorities to determine who is truly seeking asylum and who is an economic migrant. Deportation will also remain problematic, since most countries in Mediterranean Europe lack the financial and human resources to expel illegal immigrants. In addition, Mediterranean countries are unlikely to simply accept the construction of larger immigration centers within their territory without a clear system to redistribute immigrants across the Continent. Several Central and Eastern European nations opposed a recent plan by the European Commission to introduce mandatory quotas of immigrants, and that opposition is not likely to end.

In the coming years, member states will push to be given more power and discretion when it comes to reintroducing border controls. EU countries in northern Europe will also push for the suspension or even the expulsion of countries along the European Union’s external borders that are seen as failing to effectively control them. New EU member states will have a hard time entering the Schengen zone, and the resistance from some countries to accept nations like Romania and Bulgaria (which have been in the European Union for almost a decade but are still waiting to join the Schengen area) will become the new normal.

However, suspending Schengen is no solution for Europe’s refugee crisis, which could persist for many years; migrants arriving in Europe will search for weak points at frontiers and burst through them. The crisis demands interventions at every stage, from working for a ceasefire in Syria to helping Turkey and Lebanon deal with their vastly larger numbers of refugees.

Analysts agree that the European Union will not abandon the Schengen Agreement anytime soon. It will probably be reformed before the end of the decade to make it easier for countries to reintroduce border controls.

Even without a proper reform of the Schengen Agreement, member states will continue to enhance police controls at train and bus stations and at airports. Several countries already employ sporadic police controls on trains and buses, a practice that is likely to grow. Under pressure from conservative forces, many EU countries (mostly in northern Europe) will also toughen their migration laws to make it harder for immigrants to access welfare benefits.

The likely reforms to the Schengen Agreement will hurt the basic principle of the free movement of people. The main threat to the European Union is that the weakening of the free movement of people could precede the weakening of the free movement of goods, which would end the European Union in its current form.

According to Javier Solana, former NATO Secretary-General and European High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy, “the refugee crisis confronted the European Union with two stark realities. First, its member states are not all meeting their obligations, both to one another and according to international law. Second, its position regarding Syria’s civil war is unsustainable.”

Conclusion

In July 2014, Richard Hass, former director of policy planning for the US Department of State and President of the Council on Foreign Relations, compared the Middle East of today to 17th century’s Europe, in an article appropriately titled “The New Thirty Years War”. He said that the Middle East will likely be as turbulent in the future unless a new local order emerges: “For now and for the foreseeable future – until a new local order emerges or exhaustion sets in – the Middle East will be less a problem to be solved than a condition to be managed.”

The “Sykes-Picot” map of the Middle East has existed for a century due to a tenuous balance of power among states run mainly by autocrats. The “30 years war” theorists think that the Middle East’s 30 Years War began when this balance of power was blown apart by the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, which means we are at the midpoint of the remaking of the Middle East.

Just as the European 30 years war led to the formation of the modern nation-state and World Wars I and II led to the transformation of the modern nation-state and the modern European Union, the Middle East will have to travel along a path similar to Europe’s to reach a more sustainable and stable state. The new map of the region may have new borders, countries and even governments. But until then, there is a stronger and stronger feeling that the War of the Middle East will likely go on for much longer than 30 years.

One year into the formation of the coalition against Daesh, as the political stalemate continues, it is likely to expect this war to stretch for over a decade. If it has taken 15 years to defeat al-Qaeda with ground troops and full-fledged war, expecting a shorter timeframe against the Daesh “Caliphate” is likely a fantasy.

Analysts in Washington expose “Obama’s plan” to leave Syria and Iraq to the Russians and the Iranians. Both countries are a mess and there is no political will in the United States to get more involved. What could the long-term implications be of allowing the Russians and the Iranians to continue their strategies of extending their influence by fueling fractures within the neighbors and then stepping in and gaining influence over chunks of those neighbors, thereby also weakening their opponents? It is an approach that has given Russia bits of Georgia and Ukraine and has explained muscle-flexing in Belarus and the Baltics. It is the approach that has expanded Iranian influence from Lebanon to Yemen (not to mention Syria and Iraq).

For the Russian-Iranian team, the main objective is to gain leverage in any political settlement that is to come in Syria and, consequently, continued influence in Damascus. Because the United States, Europe, the Sunnis, and even the Israelis would be happy with that in exchange for putting a lid on Daesh and stemming refugee flows, it seems likely that the Russian-Iranian gambit will work. They will get what they want, and the world will declare it a victory.

Check Also

Iran’s new wave of attacks escalates threat to the world’s largest oil and gas hubs

Saudi Arabia and Qatar, the world’s top oil and LNG exporters, find their critical energy …

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News