The White House announced today that Qasim al-Rimi (or al-Raymi), the emir of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), has been “successfully eliminated” in a “counterterrorism operation in Yemen.”

Jihadists on social media speculated late last month that Rimi had been killed in an American airstrike. The New York Times first reported that “an informer” provided the CIA with information on Rimi’s location last year, thereby allowing the U.S. to track him with surveillance drones in the weeks leading up to this death.

The U.S. State Department has had a standing reward of up to $10 million for information on Rimi’s whereabouts since Oct. 2018. There is no public word if someone is collecting that bounty in the aftermath of his reported death.

The role of an informer will only further fuel AQAP’s security fears. The group has sustained a series of decapitation strikes, including the deaths of four senior figures in 2015. Rimi’s predecessor, Nasir al-Wuhayshi, was killed in a drone strike in June of that year.

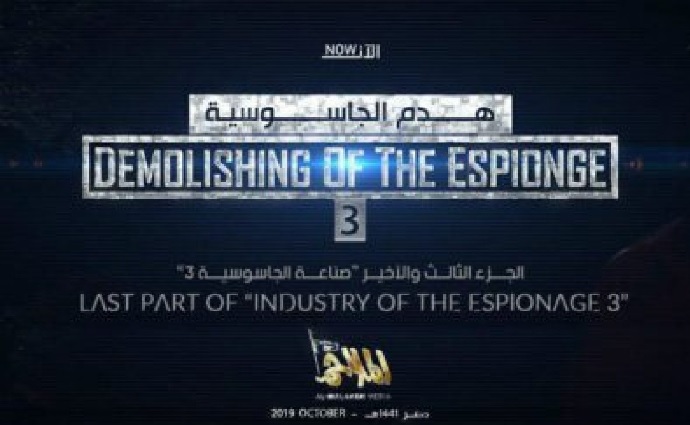

AQAP began producing a video series titled, “Demolishing of the Espionage,” in 2018. The videos demonstrate the group’s grave concern over informers and spies, some of whom have allegedly helped Saudi Arabia, the U.S. and others track the group’s middle managers and senior leaders. In addition to “confessions” from various spies, the productions included tips for evading counterterrorism efforts. Given Rimi’s reported death, their advice hasn’t totally worked.

A “deputy” to Ayman al-Zawahiri

The White House’s statement describes Rimi as both a “founder” of AQAP and its “leader,” and also as a “deputy” to al-Qaeda’s global leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri.

This description may mean that Rimi was part of al-Qaeda’s senior management team.

Indeed, Nasir al-Wuhayshi, the first emir of AQAP, was in the line of succession to replace Zawahiri should the elderly Egyptian be killed or otherwise incapacitated. Wuhayshi, who served as the aide-de-camp to Osama bin Laden in pre-9/11 Afghanistan, was one of several senior figures named in letters spelling out al-Qaeda’s succession plan. Wuhayshi also served as al-Qaeda’s global general manager, and then reportedly as Zawahiri’s top deputy, meaning he climbed up the succession line prior to his demise. FDD’s Long War Journal identified another AQAP leader, Nasser bin Ali al-Ansi, as one of Wuhayshi’s deputy general managers in al-Qaeda’s global pecking order. Al-Ansi was killed in an Apr. 2015 drone strike.

These details mean that a common distinction between al-Qaeda’s so-called “core” in South Asia and “affiliates” elsewhere is both inaccurate and misleading. Senior personnel in al-Qaeda’s global management team can be located far outside of Afghanistan and Pakistan. FDD’s Long War Journal assesses it is likely that other members of AQAP’s hierarchy also serve dual roles.

A young al-Qaeda veteran

Although he was just in his early 40s, Rimi was an al-Qaeda veteran.

His terrorist career began in Afghanistan prior to 9/11, when Osama bin Laden’s lieutenants identified him as a promising young recruit with leadership potential. While in his early 20s, al-Qaeda appointed him to serve as a trainer at the infamous al-Farouq camp, where some of the 9/11 hijackers were trained. He fled Afghanistan after 9/11, making his way to his native Yemen.

Rimi was convicted on terrorism-related charges in Yemen for plotting to assassinate U.S. Ambassador Edmund Hull and attacking foreign embassies. He was sentenced to prison.

In 2006, however, Rimi escaped from jail alongside more than 20 of his comrades. Some of these men helped rebuild AQAP. After 9/11, Osama bin Laden ordered his men to launch an insurgency inside the Saudi Kingdom. This was a disastrous move for the jihadists, as the Saudis crushed the first iteration of AQAP, forcing many of its surviving members to flee south on the Arabian Peninsula, to Yemen.

Rimi was part of a small cohort responsible for relaunching AQAP. In January 2009, he appeared in a video announcing AQAP’s rebirth. In that same video, two of his comrades explained that they were fighting to build a new Islamic caliphate.

U.S. officials have implicated Rimi in a string of plots against American interests and the U.S., including the Sept. 2008 attack on the U.S. Embassy in Sana’a and the failed Christmas Day bombing in 2009. The latter attack was carried out by a young Nigerian recruit wearing an underwear bomb, which fizzled.

In 2010, AQAP began to mass market the concept of lone or individual jihad attacks in the West. But the Islamic State, al-Qaeda’s jihadist rival, has been more successful in inspiring and directing such typically small-scale operations since 2014.

In 2017, Rimi attempted to generate new lone operations on AQAP’s behalf, releasing a video in which he called on the group’s followers to commit “simple” attacks in the West. Rimi claimed that such operations make Muslims smile. He pointed to his own smirk as evidence (see the image above). AQAP has orchestrated other, professional plots, such as the Jan. 2015 massacre at Charlie Hebdo’s offices in Paris, France. AQAP first conceived of that attack and then facilitated it.*

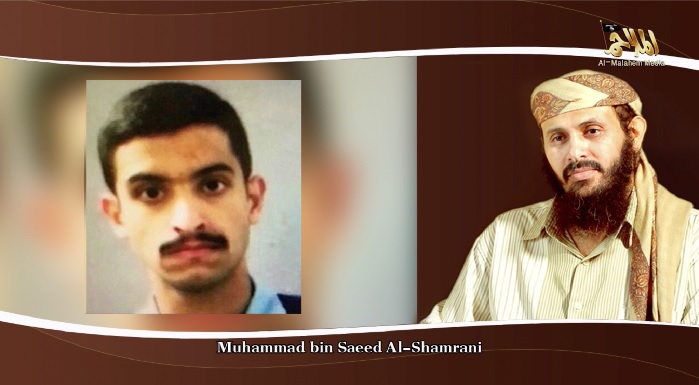

On Feb. 2 — days after Rimi was reportedly killed in a drone strike — AQAP released a video claiming “full responsibility” for the Dec. 6 terrorist shooting at Naval Air Station Pensacola. Rimi issued the claim, portraying the gunman, Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani (Al-Shamrani), as a sleeper agent who was biding his time. However, AQAP did not provide evidence showing that Al-Shamrani, a 2nd Lt. in the Royal Saudi Air Force, was known to the group beforehand.

Possible successors

AQAP does not publish an organizational chart, so we cannot be certain who is next in line to replace Rimi. Several high-profile al-Qaeda veterans could be named as his replacement — though it could also be someone else. Rimi’s possible successors include the following four jihadists.

Khalid Saeed al-Batarfi is an ideologue who is widely respected across al-Qaeda’s global network. Footage of Batarfi has been included in videos produced by other al-Qaeda branches, as well as the Taliban. The U.S. already has a standing reward of up to $5 million for information on Batarfi’s whereabouts.

Ibrahim al-Banna, an Egyptian, was sent to Yemen in the early 1990s to help build ties to Yemeni tribes and other local parties. He is also an al-Qaeda veteran who has been targeted by the U.S. in the past. The U.S. designated him as a terrorist. Al-Banna is a founding member of AQAP and has served as one of the group’s leading security and intelligence officials. He was featured in AQAP’s “Demolishing the Espionage” series.

Ibrahim al-Qosi, a Sudanese al-Qaeda veteran, was held at Guantanamo for years. Qosi personally served Osama bin Laden in a variety of roles throughout the 1990s. He was captured after fleeing the Tora Bora Mountains in late 2001 and transferred to U.S. custody. He was transferred from Guantanamo to Sudan in 2012, but then absconded for Yemen, where he became a senior AQAP leader. Qosi has been featured in al-Qaeda’s propaganda and AQAP’s security warnings, including one video in which he advised the mujahideen against spilling secrets. The U.S. has offered a reward of up to $4 million for information on Qosi’s whereabouts, noting that he was “part of the leadership team” that advises AQAP’s emir and has called for lone jihad attacks against the U.S.

Sa’ad bin Atef al-Awlaki, a Yemeni, has served as AQAP’s emir in Shabwah province. The U.S. has offered a reward of up to $6 million for information concerning his whereabouts. Should AQAP decide that a native Yemeni would be best for its top spot, then al-Awlaki is one possibility. The U.S. State Department reported that he has “publicly called for attacks against the United States and our allies.”

Again, AQAP doesn’t offer the public any visibility on its internal hierarchy or leadership deliberations. It is possible that someone else is chosen to serve as AQAP’s emir now that Rimi is dead. But these four individuals are part of a deep bench of al-Qaeda loyalists who serve within the group’s upper management.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News