Conservatives won big in Iran’s February legislative election. Disqualification of rivals, low turnout and coordination among factions may portend their victory in the 2021 presidential contest as well. Should an opportunity arise to reduce U.S.-Iranian tensions between now and then, it should be seized.

Iran inaugurated a conservative-dominated parliament (Majles) on 27 May, following an election that saw a historically low participation rate. Against the backdrop of recurrent domestic unrest, economic hardship, the COVID-19 pandemic and elevated tensions with the U.S., what happens in the new legislature could prove a bellwether for the 2021 presidential election and the direction of Iran’s domestic and foreign policy.

Shaping the 11th Majles

Three consecutive national elections – the presidential race that brought Hassan Rouhani into office in 2013, the 2016 parliamentary vote and Rouhani’s re-election in 2017 – yielded successive victories for the alliance of political camps that in Iran’s fluid factional landscape are labelled the reformist and pragmatist blocs. In the run-up to the latest parliamentary polls, on 21 February 2020, the end of that winning streak loomed, with the rival conservative bloc poised to take advantage. First the interior ministry and then an oversight body called the Guardian Council winnowed a pool of more than 16,000 aspirants. After the Council announced the disqualification of nearly two thirds of the contenders, including scores of incumbents vying for re-election, President Rouhani protested the narrow spectrum of approved candidates: “This is not an election. It is like having a shop with 2,000 of a single item”. He then urged: “Allow all parties and groups to run. This country cannot be run by a single faction”. The Supreme Policy Council of Reformists, the reformist bloc’s top body, asserted that “more than 90 per cent of the reformist parties’ candidates have been disqualified”, leaving the majority of seats either uncompetitive or contested only by conservative candidates.

” Candidates from more conservative factions worked hard to close ranks heading into the elections. “

The mass disqualifications compelled the reformists to change tack. They would not boycott the elections, they said. But rather than releasing a coordinated list of endorsed candidates, as per previous practice, they announced that they would not support candidates in 22 of Iran’s 31 provinces, including Tehran. By contrast, candidates from more conservative (“principlist”) factions, who had fared well in the vetting process, worked hard to close ranks heading into the elections. The Coalition Council (Showra-ye E’telaf) – an amalgam of traditional social conservatives and a “neo-principlist” group led by Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, a former Tehran mayor – came together with the other main camp, the hardline Endurance Front (Jebhe-ye Peydari). A prominent principlist explained: “The conservative camp was not worried about the reformists, but they coalesced to avoid repeating the bitter internal conflicts of the past”. These concerted efforts resulted in a consolidated conservative front.

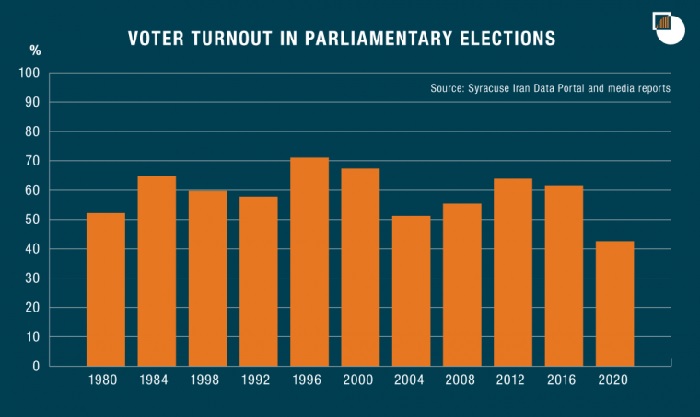

It was thus inevitable that the vote would produce a clear victory for the principlists, who took more than 220 of the 290 seats in the new Majles, while the reformists’ share of seats collapsed from approximately 120 to a fraction of that, with estimates ranging from twelve to twenty, depending on how one counts. This electoral rout was based not only on the exclusion of so many reformists but also on the smallest turnout in any Iranian parliamentary election since the 1979 revolution: a mere 42.57 per cent of voters cast their ballots, making 2020’s parliamentary contest the first in which fewer than half of eligible Iranians participated; turnout was nearly 20 percentage points down from 2016. In the capital, where the principlist list swept all 30 seats, the top candidate, Qalibaf, won with a vote total that would not have cracked the top five in 2016; the runner-up remarkably secured fewer ballots than the candidate who finished thirtieth the last time around. The weak turnout came despite Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s exhortations that Iranians view voting as “not only a revolutionary and national responsibility, but … also a religious duty”. After the vote, Khamenei decried “negative propaganda” by foreign media, adding that, “in the last two days, the pretext of an illness and virus was used, and their [Western] media did not miss the slightest opportunity to discourage people from voting”. The virus to which Khamenei referred was, of course, COVID-19, the first Iranian case of which was confirmed on 19 February, and which in the months since has developed into an acute and still untamed public health challenge compounding the significant internal and foreign pressures on the political system.

Systemic Pressures

The new legislature takes office at a time when parliament’s influence has ebbed. Lawmakers in the outgoing Majles had long expressed their discontent at being excluded from key policy decisions and at oversight bodies ignoring the legislation they had crafted. The latter held up bills passed with the Rouhani administration’s support, for example, that would have moved Iran toward joining UN conventions on transnational crime and terrorism financing, in line with reforms to which it had agreed with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). When the government in November 2019 abruptly raised gas prices, triggering widespread protests, reformist as well as principlist lawmakers criticised Rouhani for having kept them out of the loop. “It has been some time since parliament has lost its authority”, declared one legislator after the price hikes. “We had this semi-functional pillar of democracy, and now its last rites have been delivered”. Khamenei reportedly blocked parliamentary moves to impeach the interior minister – one of the legislature’s prerogatives – over the protests. And while parliament has as one of its key tasks approval of the government budget, that process was short-circuited this year, ostensibly due to the COVID-19 crisis, when parliament’s budget committee sent the draft bill directly to the Guardian Council, leapfrogging a debate in the full house.

” The November 2019 protests underscored potent and combustible public discontent over political stagnation and economic stagflation. “

Parliament’s influence waned as stresses accumulated on Iran’s political system in the months and weeks preceding the February 2020 election. The November 2019 protests, which the government forcibly subdued, underscored potent and combustible public discontent over political stagnation and economic stagflation. The COVID-19 pandemic, of which Iran had reported 180,156 cases and 8,564 deaths as of 11 June, further darkens the clouds that corruption, mismanagement and the impact of U.S. sanctions have cast over Iran’s finances. And Iran’s rivalry with the U.S., fraught since Washington’s 2018 exit from the nuclear deal, neared breaking point in January 2020 after the U.S. killed Qassem Soleimani, head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Qods Force, in Iraq, and Tehran retaliated with missile strikes on Iraqi bases hosting U.S. forces. The whirlwind ended with the tragic shootdown of a Ukrainian passenger jet that the IRGC mistook for a U.S. cruise missile.

These stresses led the country’s leadership to circle the wagons. A veteran lawmaker with national security experience explained to Crisis Group that the November protests had “intensified the government’s securitised approach. There were concerns that a competitive electoral atmosphere could get out of control. … The military threat from the U.S. and possibility of a confrontation also played a part”. The leadership, he said, therefore “wanted a management system suitable for a [military and economic] war footing and crises. This meant that the legislature should coordinate with the executive branch and other pillars of the state”. A principlist lawmaker echoed this view, offering the following rationalisation to Crisis Group: “This parliament understands that, under the current circumstances, it’s not necessarily a bad thing if civil society and elected institutions lose power. To the contrary, in a sensitive situation and facing external threats, a consolidation of power [across the political system] is not only helpful, but actually necessary”.

None of this suggests that Iran’s political system will find a better way to govern, however. In remarks at the new parliament’s inauguration, President Rouhani asserted that “favouring national over partisan and factional interests will be the basis for cooperation between the government and parliament”. Yet partisan and factional interests are likely to surface both within the Majles and between the two branches ahead of next year’s presidential election. Not all principlists supported the pre-election manoeuvring that led the conservative coalition to form, and their factionalism could resurface despite calls for what has been dubbed “pious competition”, ie, keeping debates internal rather than letting them spill out on parliament’s floors. While Qalibaf, a former IRGC commander and three-time presidential aspirant, was swiftly and by a sweeping margin elevated to the speakership, the veteran lawmaker with national security experience explained that, “to the Endurance Front, Qalibaf is not a real, original principlist. He’s an opportunistic power seeker who will make deals with whoever benefits him, even the reformists”. A principlist lawmaker acknowledged the possibility that fault lines could quickly emerge, adding: “The main challenge could be [former President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad’s shadow, because his team” – that is to say, dozens of veterans from his administration now in parliament – “want to use the Majles as a platform for his candidacy in the 2021 [presidential] election”.

” A senior reformist figure acknowledged that the bloc’s prospects in the presidential election are poor. “

Indeed, all eyes are already on the 2021 race to succeed Rouhani, who, having served two consecutive terms, cannot stand for a third. For reformists, the February parliamentary contest underscored several challenges that bode ill for their prospects in the presidential election: internal divisions, close association with the Rouhani administration and its meagre domestic achievements, and near-total exclusion from the electoral process. A senior reformist figure acknowledged that the bloc’s prospects in the presidential election are poor, while speculating that an accumulation of challenges could prompt collaboration between reformists and moderate principlists even in the event of a conservative takeover. “The next administration cannot remain monolithic if it wants to address the major issues the country is facing”, he remarked. “Until then, it is better for the reformists to remain spectators rather than actors. Considering the [country’s] lack of resources and capabilities, it won’t be easy for the [principlists], and hopefully the system will come to the conclusion that it should open up the political environment”. A senior official in the Rouhani administration likewise tried to strike an optimistic note, stating that, “times of crisis create new opportunities for activism”. Still, he acknowledged, “reformist elites are not optimistic that they will still be able to participate in power, because they won’t be let in”.

For the principlists, on the other hand, securing the presidency after eight years would consolidate conservative control over Iran’s most powerful elected and unelected institutions, ranging from the judiciary (helmed by Ebrahim Raisi, whom Rouhani defeated in 2017) to the legislature (whose new speaker Rouhani also bested in the 2013 race) to the IRGC and various oversight bodies like the Guardian Council. That is an alignment that could prove crucial down the road in deliberations over Supreme Leader Khamenei’s succession, which one principlist analyst described as now “doubly complicated and sensitive” because of the unprecedented domestic and international challenges facing the Islamic Republic.

In the meantime, the Majles may prove a testing ground for 2021 – certainly in terms of ideas and arguments over matters of governance, and perhaps also in terms of presidential candidates. The Rouhani administration will likely find itself at loggerheads with a conservative majority on both domestic policy, including the ailing economy, which Khamenei has identified as a key concern, and foreign relations. Indeed, though the legislature holds little sway over the conduct of foreign policy, it can still play a part on the margins. As a procedural matter, Speaker Qalibaf now has a seat on the Supreme National Security Council, which coordinates major decisions across senior political and military bodies. And, as a matter of policymaking, a conservative Majles can do more to limit the Rouhani administration’s room for manoeuvre than the previous parliament could do to expand it, whether by publicly grilling cabinet members or by denouncing the government’s performance from the legislative stage. A senior Iranian diplomat hazarded that the new parliament “is likely to adopt a much more hardline approach and might even compel the Supreme Leader to take a much harder line. He is not inclined to escalate, but he goes with the flow”. “Principlists believe that the compromises Rouhani made [ie, the nuclear deal] bore no fruit and even put the country in a worse situation compared to the [previous] time”, said the lawmaker with national security experience. “So, to them, the country should showcase its power as a way to exit the current deadlock. The new parliament is aligned with those who advocate for Iran’s withdrawal from the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, call for a firmer response to U.S. aggression, have little confidence in the Europeans and seek closer ties with the East”. Underscoring the point, Qalibaf, in response to President Donald Trump’s 5 June tweet urging Iran to “make the big deal” with his administration, reached for a Quranic verse exhorting: “Do not back down and call for peace while you have the upper hand”.

” The Rouhani administration will likely find itself at loggerheads with a conservative majority on both domestic policy and foreign relations. “

Rouhani’s pragmatist camp, for which the nuclear deal was a signature achievement, has a particular interest in salvaging the agreement during his final year in office, and securing relief from U.S. sanctions. The parliamentary election results make that more challenging but not impossible: the legislature has a modest role, compared to the presidency, the military and the Supreme Leader, within the consensus-driven process that characterises Iran’s strategic decision-making. What those results clearly signal, however, is the ever-growing probability that conservatives will capture the presidency next year, and with it, the last pragmatist-held power centre. In that sense, the 2020 election means that should a diplomatic window open between Tehran and Washington, either in the coming months or after the next U.S. administration takes office in January 2021, it ought to be seized, lest the Iranian political system’s resolve against compromise harden.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News