Romanian and Bulgarian interests have diverged on many occasions throughout history, but their outlooks have recently become more aligned. For one thing, both countries have fostered a competitive dynamic to exploit their advantageous position near the Black Sea, or to join the EU and the Schengen Area. Their narratives regarding China are also similar. Today, both countries are part of the 17+1 mechanism, an annual forum between China and initially 16 Central and Eastern European countries (CEE), to which Greece was added in 2019.

Diplomatic ties to China date back to 1949, when Romania and Bulgaria fought for the distinction of becoming the second country, after the USSR, to recognize the People’s Republic of China (PRC). One former high-ranking Romanian diplomat recalled that Bucharest developed the initiative in early 1949, before the official proclamation of the PRC, but Moscow intervened against it. Bulgaria thus won the race, becoming the second country in the world to establish ties with Chairman Mao Zedong’s new government on October 4, just one day ahead of Romania.

More recently, competition for China gained momentum in 2013 with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the 17+1 mechanism. Leveraging their geographic position and socio-economic advantages, the honor of being the “Chinese Gateway in Europe” was a goal for both Romania and Bulgaria. On one hand, Romania placed all its strength in the first phase (2013 to 2015) but lost interest along the way. On the other, Bulgaria followed a more linear path and has lately succeeded in generating small yet successful Chinese stories.

Romania ardently reignited its China story in 2013 when the then-Prime Minister Victor Ponta announced his aim to raise bilateral relations to the level of a strategic partnership. During the 16+1 summit of 2013 in Bucharest, the Romanian government developed more than half a dozen project proposals, for which Memoranda of Understanding with Chinese companies were signed. Yet, by 2020, all of them had been abandoned because of difficult negotiations, lack of interest on both sides and external pressures. The Cernavodă Nuclear Power Plant saga was the longest Chinese negotiation story in the region. Negotiations lasted six years, only to be called off in early 2020 due to a number of factors, including financial disagreements between the two sides. Alongside Cernavodă, Romania signed agreements for three other energy projects worth a combined $2.6 billion in 2013. The modernization of a thermal power plant was dropped within a year of an agreement being signed, with officials citing strange reasons such as lacking some necessary approvals, while the other two projects were tacitly shelved because of political instability.

Romania’s priorities changed during this period. Since 2013, Romania has witnessed six governments and began hosting a US ballistic missile shield. Meanwhile, Russia invaded Crimea and China and the US became engulfed in a trade war. While Bulgaria maintains strong relations with Russia, Romania is fearful. Because of the ‘Russian factor’ – the influence that fear of a possible Russian invasion has over the foreign policy of most CEE countries – Romania chose to stand with the US. It did so by hosting two NATO military bases, including the Deveselu missile shield. On the other side of the Danube, Bulgaria doesn’t fear Russia very much at all.

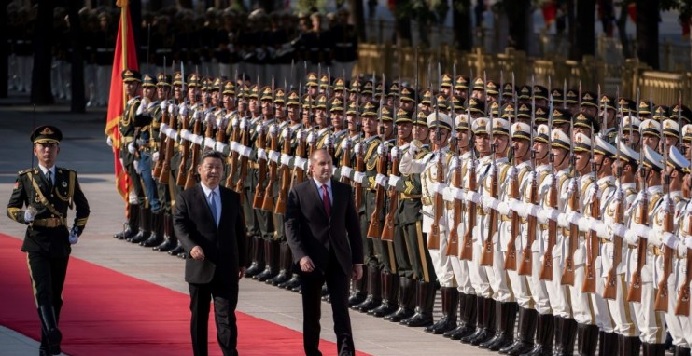

Both Romania and Bulgaria have shifted their approaches towards China. While Romania seems to look west and distance itself from Beijing, Bulgaria has lately become more interested in Chinese relations. At the beginning of the 17+1 mechanism, Bulgaria was rather reticent, with then-Prime Minister Boyko Borisov skipping the 2014 Belgrade summit. During the same period, Romania seemed very close with China, hosting the 2013 summit, sending its prime ministers to other then-16+1 summits, and signing several project agreements. But recently, Romania’s enthusiasm for China has transferred to Bulgaria – a country which not only hosted the then-16+1 summit in 2018 but succeeded where Romania failed by upgrading relations with China to a strategic partnership. This shift was clearly demonstrated in 2019, when both countries celebrated 70 years of bilateral relations with China. While not even a Romanian minister visited China last year, Bulgaria sent President Ruman Radev to meet his Chinese counterpart President Xi Jinping in Beijing. This shift isn’t just evident on political and strategic levels, but also on an economic level.

After welcoming Chinese investment in the Port of Varna and Port of Burgas, Bulgaria arrived at the then-16+1 summit in Sofia in 2018 with many proposals for important infrastructure projects. In 2019, Bulgaria invited China National Nuclear Corporation to bid for the development of the Belene Nuclear Power Plant. Similar to Cernavodă, Belene is Bulgaria’s largest energy project, requiring a $10.7 billion investment. The project has attracted the interest of Russia’s Rosatom, China’s CNNC and Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power Co. It seems more feasible than Cernavodă, given North Macedonia’s expressed interest in buying energy from the Belene Nuclear Power Plant.

Competition between Romania and Bulgaria is strongest along the Black Sea coast, where the stories of three ports converge. Romania’s Port of Constanța is the largest port in the Black Sea region but has generated less investment than the Ports of Varna and Burgas. The only significant Chinese presence in Constanța is that of China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation (COFCO), which owns a cereal terminal in the Port of Constanța and three grain storage facilities in southern Romania. However, COFCO’s presence came about only after acquiring Nidera, a Dutch company and former owner of these facilities. In Bulgaria’s Port of Varna, China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC) wants to spend $120 million developing the port’s infrastructure to become the country’s first modern port equipped with warehouse facilities. Burgas, the other important Bulgarian port, attracted a $20 million Chinese investment in a logistics hub that aims to facilitate Chinese trade from the Port of Piraeus to Europe.

Despite being home to the Black Sea’s largest port, Romania couldn’t dream of replicating the success story of the Port of Piraeus by transforming Constanța into a Chinese infrastructure hub. This is because less than 50 km away from Constanța’s cargo zone there is a US military base. While a port call in Constanța by Chinese military ships in 2012 was acceptable, the US is unlikely to agree to China controlling the biggest port on the Black Sea, just a few dozen kilometers from its military base.

Looking toward private investment in both countries, one can also see competition between Romania and Bulgaria. Each country hoped to be the “Chinese Gateway in Europe” and Chinese investment was seen as a windfall. Aside from their geographic position, both countries seek to attract foreign investors by promoting their low labor costs and skilled workforce. While Huawei established a regional support center in Romania and Great Wall Motor company built a factory in Bulgaria, few significant Chinese investments have materialized in recent years.

Although China-Romania and China-Bulgaria relations appear positive, Chinese investment is low in both Romania and Bulgaria, compared to Western countries. According to German think tank MERICS, Romania attracted $1.3 billion in Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) between 2000 and 2019, compared to $0.45 billion in Bulgaria. By comparison, Germany attracted $25 billion in Chinese FDI during the same period and the US received $149.9 billion. This low investment rate speaks volumes about the 17+1 mechanism, the BRI and regional ties to China. Eight years since the establishment of the 17+1 and seven years since the BRI was announced, no proposed Chinese project has been completed in Romania or Bulgaria. Although Romania showed interest in attracting Chinese investments – going as far as joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in 2018 – there is no Chinese success story in the region, even in infrastructure.

On the contrary, there are many failed projects in both countries. In Romania, all four important energy projects failed, together with dreams of Chinese-built high-speed rail lines. Having signed investment agreements with China much later, Bulgaria has witnessed just two failed projects: the Great Wall Motor plant near Lovech and the Plovdiv Airport. The Great Wall Motor plant was a private Chinese investment that failed because it couldn’t penetrate the European market. Meanwhile, the Plovdiv Airport was hailed as an important project in the region but after winning the tender, the HNA-led consortium decided to withdraw, presumably because of HNA’s debt problems combined with Beijing’s tighter control over overseas investments. The consortium had won a 35-year concession to operate, repair and maintain the airport in Plovdiv, and had even announced it would double its initial investment promise of $93 million. If implemented, HNA Group wanted to transform Plovdiv Airport into a cargo and regional tourist hub for Central and Eastern Europe. Together with the Port of Burgas and the Port of Varna logistic and infrastructure investments, this project would have given Bulgaria the status of the “Chinese Gateway to Europe”.

Competition between Romania and Bulgaria reignited years ago, in part because of a desire to lure Chinese investment to the region. But while Bulgaria was more cautious in its relations with China, Romania enthusiastically embraced China, only for relations to weaken year-on-year since 2013. Romania’s narrative was influenced not only by disappointment with Chinese investments, its closeness to the US and its own political instability, but also by the Huawei scandal and growing tensions between China and the US, combined with the “Russian factor”. Bulgaria – with less FDI than Romania but a steadier approach towards Beijing and more flexibility balancing between the US and China – has shown more success in attracting Chinese investments, while avoiding Western criticism.

Some policymakers in Washington believe CEE countries, including Bulgaria and Romania, are ‘in bed’ with China. But the dynamics of these relations are often misunderstood. While Bulgaria may continue to seek ties with China over the coming years, Romania has already chosen the side of the US by abandoning the Cernavodă Nuclear Power Plant. Given it could also soon restrict Huawei operations in building its 5G network, prospects for Romania-China relations are gloomy.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News