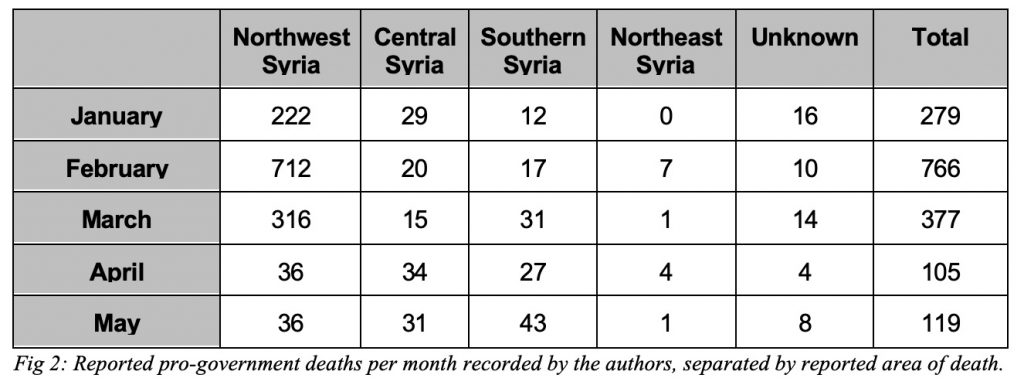

After a brief but deadly Turkish offensive in Idlib, a new phase of the Syria war began on March 5 with the signing of a Turkish-Russian cease-fire deal. Reported deaths dropped drastically following the cease-fire, and this spring has been defined by the slow attrition of pro-regime forces due to the two ingoing insurgencies in south and central Syria and the two frozen frontlines in the northwest and northeast. The author and Trenton Schoenborn recorded 600 reported pro-government combat-related deaths between March 1 and May 31, 2020. These numbers show a sharp decrease in the level of violence in northwest Syria when compared to reported deaths in the previous two months of this year. They also demonstrate gradually increasing levels of violence in southern and central Syria, where the regime faces insurgencies by ex-rebels and ISIS militants.

Methodology

This report relies on pro-regime Syrian Facebook pages to document deaths within the ranks of the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) and allied forces. Martyrdom announcements were collected during this time in a joint effort by the author and Trenton Schoenborn. Announcements are shared by individual friends and family, community Facebook pages, and semi-official unit pages. They usually include the martyr’s hometown or governorate, his rank, where he died, and, to a lesser extent, the unit he fought in. Most men receive a posthumous promotion, but all such cases have been accounted for in the data below.

While this is an excellent source of primary data — far more accurate than the numbers claimed by opposition forces or official regime media — there are several important limitations. Firstly, reporting about military losses on social media is still technically illegal in Syria. Thus, it often goes through phases of suppression where either communities do not feel safe posting about their slain men, or the regime does not disclose the deaths of men to their families. Secondly, the deaths of reconciled rebels are almost wholly unreported. Martyrdom reporting is a communal activity, relying on family, friends, or community leaders to publicize the death of a local. Rebels who have reconciled and joined the ranks of regime forces rarely receive such honors, and if they do, news of their deaths is rarely shared outside their community. This second factor makes it particularly difficult to find out about such deaths due to the impossibility of searching the Facebook pages of every Syrian community. Outside of ex-rebels, the deaths of poor and single loyalist martyrs often go unreported as there is no one in their hometowns with the means to share the news.

Therefore, the data presented below represents a baseline for the number of deaths among the Syrian regime security forces, with the true number of killed men being much higher.

Back to counter-insurgency

To borrow an over-used cliché, a new phase of the Syria war began on March 5. Turkey ended its week-long offensive in Idlib by signing another cease-fire deal with Russia.1 Under the terms of the deal, each country would keep its respective side from breaching the new frontlines and would begin joint patrols along the M4 highway, running from Saraqeb (under regime control) to Ariha (under opposition control).2

This cease-fire capped off the deadliest week for Syrian regime forces in recent years. Turkish drone and artillery strikes, alongside rebel fighters, killed at least 405 pro-regime fighters between February 27 and March 5. Damascus also lost at least 73 armored vehicles to drone strikes and rebel anti-tank guided missile operators during the Turkish operation.3 Reported deaths dropped drastically immediately following the cease-fire, and dropped again several days later following delayed martyr reports. By the second week of March, there were no major military operations anywhere in the country.

Instead, this spring has been defined by the slow attrition of pro-regime forces due to the two ingoing insurgencies in south and central Syria and the two frozen frontlines in the northwest and northeast.

“Turkish drone and artillery strikes, alongside rebel fighters, killed at least 405 pro-regime fighters between February 27 and March 5.”

Combat deaths in spring 2020

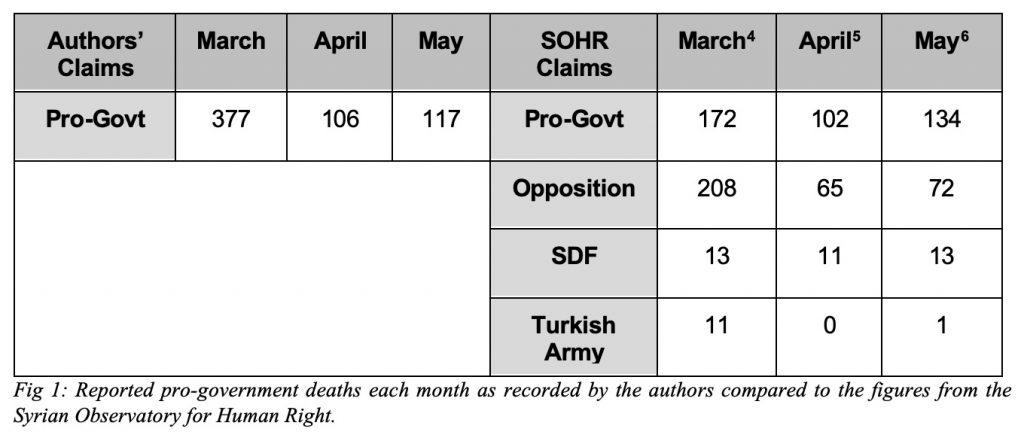

The author and Trenton Schoenborn recorded 600 reported pro-government combat-related deaths between March 1 and May 31, 2020. It is worth noting that in this same period, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights claims to have documented 408 pro-government deaths (including 55 allied foreign fighters), 345 opposition deaths, 37 deaths among the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and 12 killed Turkish soldiers.

These numbers show a sharp decrease in the level of violence in northwest Syria when compared to reported deaths in the previous two months of this year. They also demonstrate gradually increasing levels of violence in southern and central Syria, where the regime faces insurgencies by ex-rebels and ISIS militants.

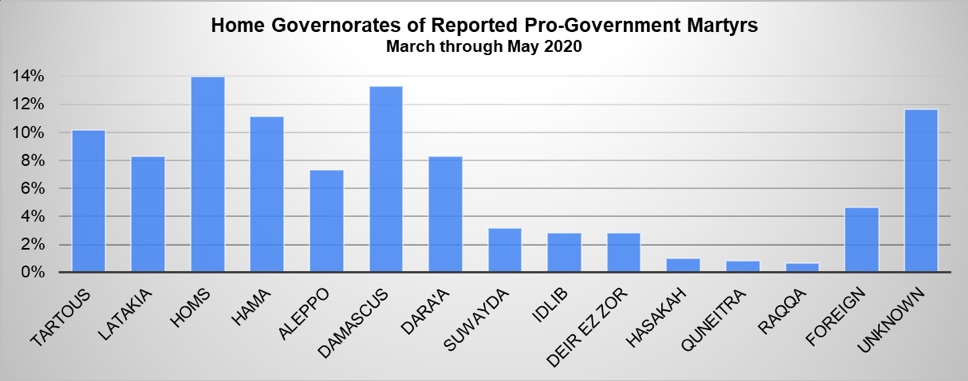

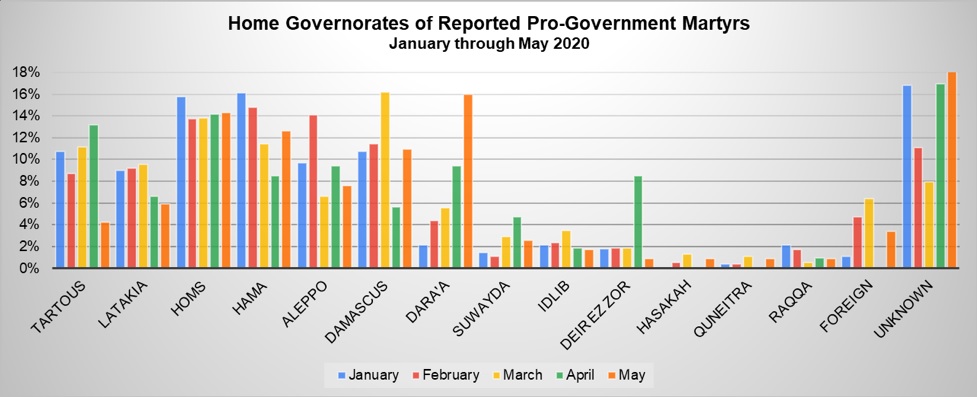

The chart below shows the percentage of the 600 pro-government martyrs documented from March 1 through May 31 that hailed from each governorate. Tartous, Latakia, Hama, and Homs have historically represented the core of loyalist recruitment, as these governorates have substantial Alawi and Ismaili communities. During this period, 43.5 percent of reported martyrs came from these four governorates.

However, when examined on a month-to-month basis there is a clear downward trend in the proportion of martyrs from these four governorates. During the intense fighting in northwest Syria in January and February, the four core governorates amounted to 51.5 percent and 46.5 percent of all reported deaths. In May, only 34.5 percent of reported pro-government martyrs came from these areas. This data supports the long-known fact that the regime’s offensive and “elite” units are more heavily staffed by Alawites and Sunnis from trusted loyalist communities. When there are no major offensive actions, fewer men from these governorates die.

The chart below also hints at the proportionally increasing lethality of the insurgency in Daraa, demonstrated by the growing representation of men from Daraa over the course of the year. In May, Daraa had the highest proportion of martyrs out of any governorate. Yet this does not imply that the regime has begun sending reconciled men from Daraa to other fronts in increased numbers. Rather, 13 of these 21 men died in or near their homes, targets of ex-rebel and ISIS cells.

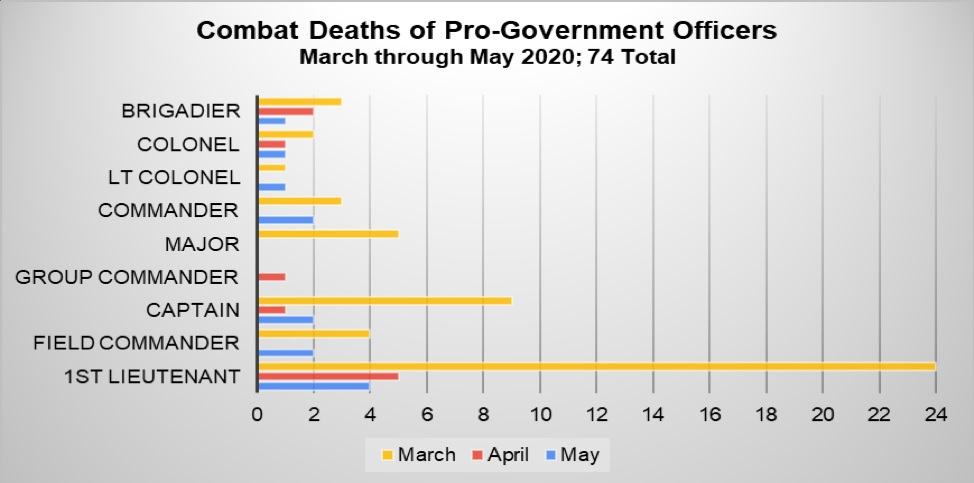

At least 41 pro-government officers above the rank of first lieutenant were killed in combat during this period. An additional 33 first lieutenants were also reportedly killed. The vast majority of these deaths (51) occurred in March, and of those, 39 were killed during the Turkish campaign between March 1 and March 5. However, high ranking members of the security services continued to be killed across the country after the cessation of major military operations.

In Idlib, a brigadier commanding an artillery unit of the Republican Guard’s 105th Brigade was killed on April 5, just two weeks after another brigadier commanding a different artillery unit was killed in Aleppo. On April 18, ISIS cells in Daraa killed the chief of staff and his aid — a brigadier and colonel — of the 3rd Division’s 52nd Brigade. Meanwhile ISIS cells in central Syria killed a number of high-ranking men in April and May, including the Air Force Intelligence commander of the Dibsi Afnan sector of Raqqa; the commander of a local defense militia backed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in east Hama; an IRGC general near Ithriya, Hama; and a commander of the Shaitait Tribal Forces near Shoula, Deir ez-Zor. Also of note, the former commander of the Deir ez-Zor Military Airport died in a car crash on April 29.

“[These numbers] also demonstrate gradually increasing levels of violence in southern and central Syria, where the regime faces insurgencies by ex-rebels and ISIS militants.”

Northwest Syria goes quiet

The Syrian regime launched a series of offensives on the rebel-held greater Idlib pocket beginning in early 2019, first capturing northwest Hama and southern Idlib over the course of spring and summer, while failing to make any headway in Latakia. In late January 2020, the Syrian Army and allied local and foreign militias launched a new offensive aimed at seizing all of western Aleppo and eastern Idlib provinces. Government advances swallowed a dozen Turkish observation posts — ostensibly built to ensure a lasting cease-fire.

The Turkish Ministry of Defense claimed to have struck 115 regime targets when regime fire killed five Turkish soldiers on Feb. 10, but no evidence of such attacks could be found either through public sources or contacts on the ground.7 On Feb. 12, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared that the Turkish army would “strike regime forces everywhere from now on regardless of the [2018] deal if any tiny bit of harm is dealt to our soldiers at observation posts or elsewhere.”8 On Feb. 27, a Russian jet killed 37 Turkish soldiers, finally triggering Erdogan’s threatened strikes.9 Beginning late on Feb. 27 and lasting until March 5, Turkish drones and artillery struck hundreds of SAA, Hezbollah, and Iranian positions across Hama, Idlib, and Aleppo.

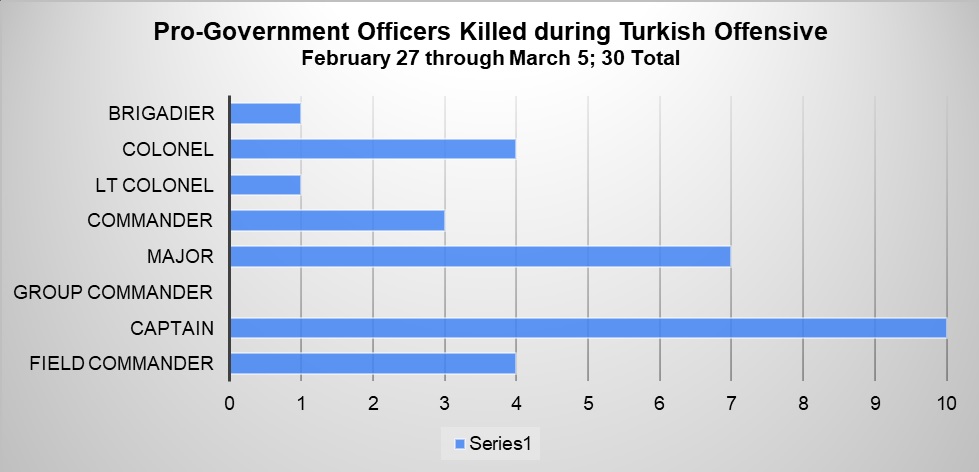

In one week, this Turkish offensive, supporting a rebel ground offensive, killed at least 405 pro-regime fighters, including 30 high-ranking officers, and led to the destruction or capture of 73 armored vehicles. Among the dead was an entire Republican Guards operations room consisting of the commander of the 124th Brigade, his battalion commander, and a lt. colonel and major from the brigade; a Syrian Hezbollah commander; and the operations commander and three field commanders of the Tiger Force’s Taha Regiment.

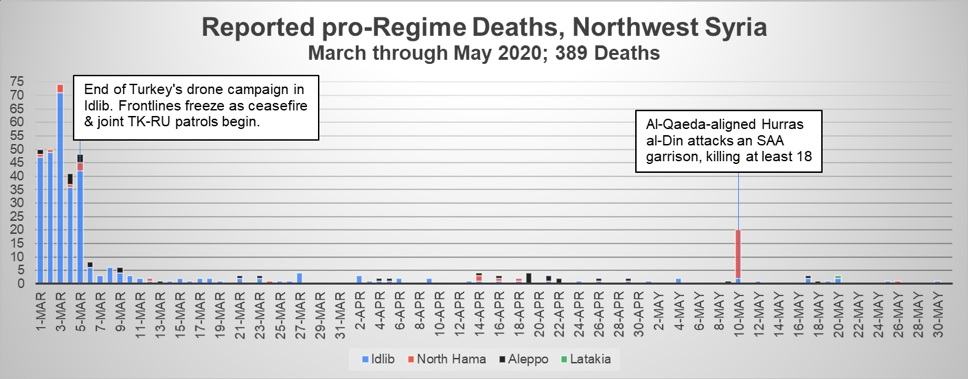

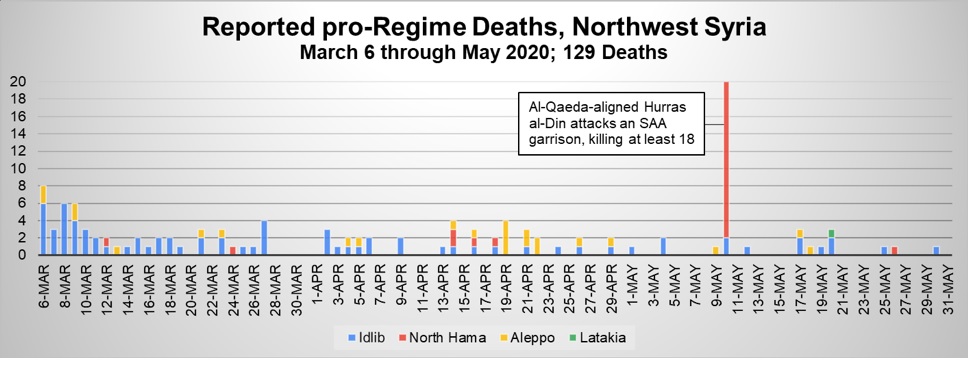

Following the March 5 cease-fire, violence along the northwest frontlines has dropped dramatically. Of the 389 documented deaths on this front, only 129 occurred after March 5. The sudden drop-off in violence is clearly visualized in the chart below.

Pro-government fighters have continued to die since the cease-fire, but at a generally decreasing rate. It is important to note that while most of Idlib is controlled by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the al-Qaeda-linked Hurras al-Din (HaD) maintains a high level of operational freedom that has allowed it to ignore the cease-fire and continue to attack regime positions with intermittent sniper and artillery fire. This group is also responsible for the May 10 attack on regime-held Tanjarah, killing at least 18 members of the 85th Brigade’s 334th Battalion.

The question remains: how long will the current cease-fire hold? While Syria in general, and the northwest especially, has been a story of failed cease-fire after failed cease-fire, this one may be different. This is the first cease-fire to follow a massive foreign military intervention against the Syrian regime. Turkey appeared to demonstrate, through military power, its unilateral decision to define the eastern Idlib border as it currently stands. Less clear is where Turkey stands on the demarcation of the southern edge of rebel-held Idlib. While opposition groups still control a pocket of villages south of the M4, Turkey and Russia have declared the M4 a demilitarized zone and have conducted a series of joint patrols along it.

Meanwhile, Turkey continues to deploy tanks, artillery, and anti-air defense systems in Idlib. These deployments could simply be security measures for the thousands of Turkish troops stationed inside the governorate, or they could be a sign that Turkey intends to maintain this cease-fire by force if necessary. However, the question of what to do about HaD and the unclear status of the area south of the M4 remain crucial stumbling blocks moving forward. Unless HTS and Turkey effectively destroy or rein in the hardline faction soon, little can be done to prevent the looming Syrian regime offensive.

“The question remains: how long will the current cease-fire hold? While Syria in general, and the northwest especially, has been a story of failed cease-fire after failed cease-fire, this one may be different.”

Central Syria’s ISIS problem

At the end of 2017, the Syrian regime and Russian President Vladimir Putin proudly proclaimed their militaries’ victory over ISIS.10 The terrorist group had lost all of the urban centers — and allegedly the rural areas — it once controlled west of the Euphrates River. Nevertheless, ISIS has been able to effectively wage a sophisticated and deadly insurgency throughout regime-held central Syria for more than two-and-a-half years.

ISIS has employed improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and mines, small arms, anti-tank guided missiles and rocket-propelled grenades, car bombs, and fake checkpoints to repeatedly ambush Syrian regime and Russian forces in the Deir ez-Zor, Homs, Raqqa, and Hama governorates. ISIS attacks have spanned more than 15,000 square miles — striking as far west as Khunayfis (just 40 miles from Damascus governorate) and as far north as Rahjan, Hama (just 15 miles from Idlib governorate), and along the length of the Euphrates from Boukamal in the south to Dibsi Afnan, along Lake Assad in the north.

ISIS has proven to operate a robust intelligence gathering system in central Syria. The group routinely kills high-value targets such as Syrian and Iranian commanders using mines and IEDs and has successfully avoided regime strongpoints during its deep pushes “behind enemy lines,” finding roads through undefended parts of the countryside. In doing so, ISIS has managed to effectively control territory at various times, most recently controlling the crucial Bishri Mountains bordering the Raqqa, Homs, and Deir ez-Zor governorates from April 2019 through February 2020.

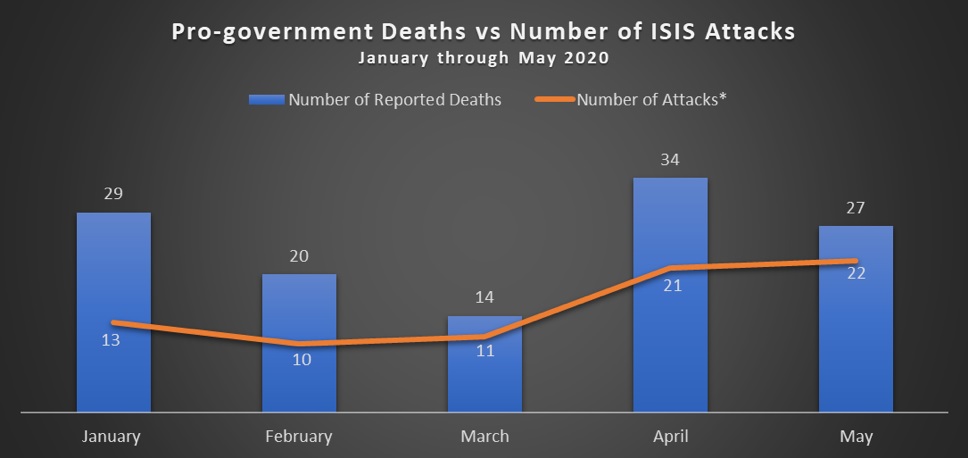

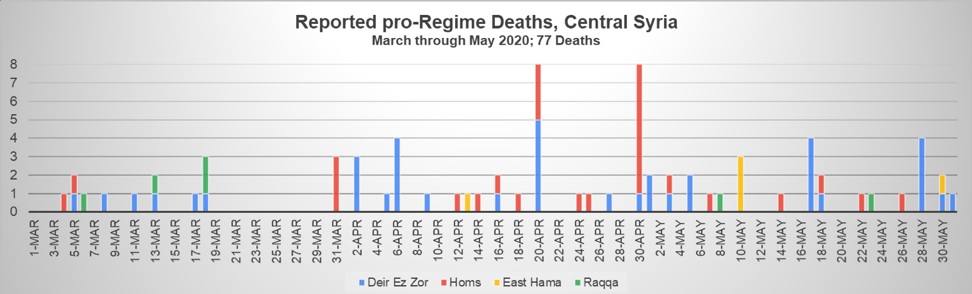

Despite ostensibly losing control of Jabal Bishri in February, and enduring sustained anti-ISIS operations in April and May, ISIS has continued to carry out attacks this spring. The number of reported deaths in central Syria caused by ISIS, as well as the number of apparent attacks11 the group has carried out, have steadily risen since their low in March. April had the most reported pro-government deaths this year and May had the greatest number of apparent attacks.

April and May also saw attacks spread further north. On April 10, ISIS militants managed to bypass regime security forces stationed throughout east Hama and attacked the town of Rahjan, just 15 miles from the border with Idlib. During the attack, militants killed the commander of a local Iranian-backed militia before safely withdrawing back through regime lines to the desert to the south.

ISIS managed to carry out equally intel-intensive attacks in May, first killing the Air Force Intelligence’s lt. colonel in charge of the Dibsi Afnan sector of north Raqqa. This is the northernmost known ISIS attack in regime-held Raqqa and struck in an area that has long served as a major center for Air Force Intelligence recruitment. Two days later, on May 10, ISIS targeted the car of an IRGC commander with an IED near Ithriya, Hama, killing him and two others. On May 30, a Liwa al-Quds fighter was killed in east Hama, likely by a mine.

The main difference between April and May was the lack of major ambushes or large, complex operations in the later month. It seems the extensive regime anti-ISIS operations, conducted across the entirety of the central region during the month, limited ISIS to smaller attacks. Still, the terrorist group effectively used mines and IEDs to regularly harass patrolling security forces. Furthermore, ISIS was able, as it did in April, to successfully create a fake checkpoint on the Palmyra-Deir ez-Zor highway, resulting in the death of at least four soldiers and one civilian. While regime forces carried out numerous and widespread anti-ISIS operations, the trend appears to show ISIS cells facing ever fewer geographic constraints.

Southern Syria’s very real insurgency

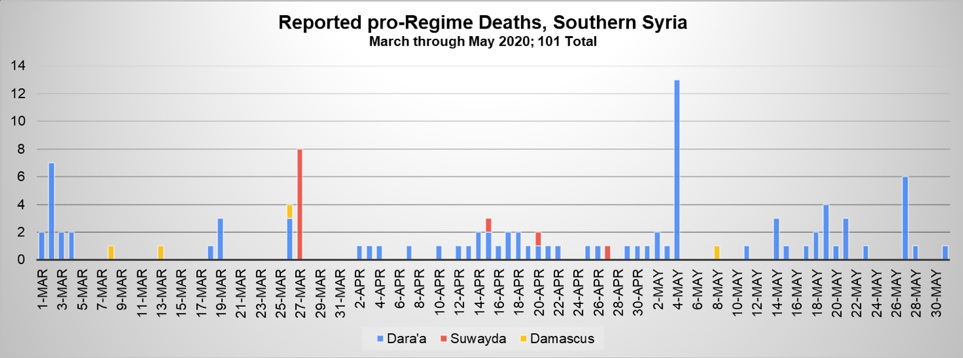

Signs of a burgeoning insurgency revealed themselves almost immediately after the regime’s patchwork victory was imposed over the southern province of Daraa in July 2018. Abdullah al-Jabassini, an expert on the political and military affairs of Daraa, documented at least 530 violent incidents killing more than 480 individuals between August 2018 and May 2020.12

While initially dominated by two loosely formed insurgent groups of ex-rebels, insurgent attacks have increasingly been carried out by ISIS cells. Targets include everyone from soldiers staffing regime checkpoints, reconciled rebel fighters and leaders, local political leaders, and high-ranking regime officers.13 On top of the targeted attacks is rampant lawlessness that has led to the deaths of civilians.14 For the purpose of this paper, only those men who are confirmed to have been members of the regime’s military or political bodies are documented.

Daraa’s insurgency appeared to reach a peak on May 4, when insurgents stormed the police station in Muzayrib and killed all nine officers in retaliation for the murder of their leader’s son.15 The regime finally mobilized a massive anti-insurgency force — consisting of nearly every available 4th Division fighter from Damascus16 — and entered the town en masse. Russian-led negotiations ensued while attacks continued throughout the region. The current agreement as of the end of May involves a new round of reconciliation in which ex-rebel fighters join the 4th Division’s 42nd Brigade or 666th Regiment and gradually begin taking over internal checkpoints currently run by “outsider” 4th Division fighters.17 It therefore appears that locals will continue to take greater charge of security in their towns in western Daraa.

“Daraa’s insurgency appeared to reach a peak on May 4, when insurgents stormed the police station in Muzayrib and killed all nine officers in retaliation for the murder of their leader’s son.”

The summer ahead

This spring has been one of the quietest three months Syria has witnessed since the war began. Still, Damascus faces serious issues in the southern and central parts of the country where the ongoing insurgencies show no signs of abating. Meanwhile, Syria’s economy is in freefall and the country faces the very real threat of famine during the next year.

These internal crises coupled with Turkey’s recent massive show of force and the continued influx of Turkish military hardware into Idlib make a new regime offensive to seize the remainder of the greater Idlib pocket in the near future unlikely. While cease-fire violations — carried out by both sides — occur on a weekly basis, the reality is that very few men are dying in the northwest. The exception remains HaD and its cohort of small extremist factions.

These hardliners, who have explicitly denounced the cease-fire and have strong ideological ties to al-Qaeda, carried out a second raid on regime positions on June 8. Four days later they formed a new operations room with the explicit intention of continuing to violate the cease-fire agreement. Sources in Syria have told the author that the regime is preparing for a new military campaign specifically targeting these hardline factions. Yet these groups have no official territorial control and can theoretically flow in and out of HTS lines at will, thus making a targeted and limited offensive impossible. The U.S. drone strike on HaD leader Khaled al-Aruri on June 14 provides a possible alternative, wherein Turkey provides intelligence on HaD movements to the Russians, who in turn carry out preemptive strikes. It is possible that something like this already occurred on June 13, when regime planes struck a gathering of rebels in al-Barah, as they were reportedly preparing to raid regime positions.

In the absence of any such intel-sharing agreement between the Turks and Russians, a regime offensive on Jabal Zawiyah appears inevitable. While Turkey will almost certainly prevent the regime from crossing the M4, an assault on the towns and farmland south of the highway will still create immense suffering for the civilians and internally displaced persons crammed into the Idlib pocket. For the regime, such an offensive will only hasten the rapidly approaching total collapse of the state’s economy and subsequent mass famine. Whatever happens in the coming months will no doubt be decided by leaders residing outside of Damascus — a story all too familiar for Syria.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News