While most international attention has been focused on the “post-caliphate” Islamic State insurgencies in northeast Syria and Iraq, ISIS has steadily carried out an ever-expanding insurgency against the Syrian regime and its allies in central Syria. The insurgency began immediately following the Syrian regime’s capture of this area in late 2017 and has continued unabated since.

On August 18, 2020, Russian Major General Vyacheslav Gladkikh was killed alongside a senior Syrian regime commander and four others while driving through the Tayem Gas Field near Deir Ez Zor city. These were the 20th and 21st high ranking officers killed by ISIS in central Syria since January 2019.

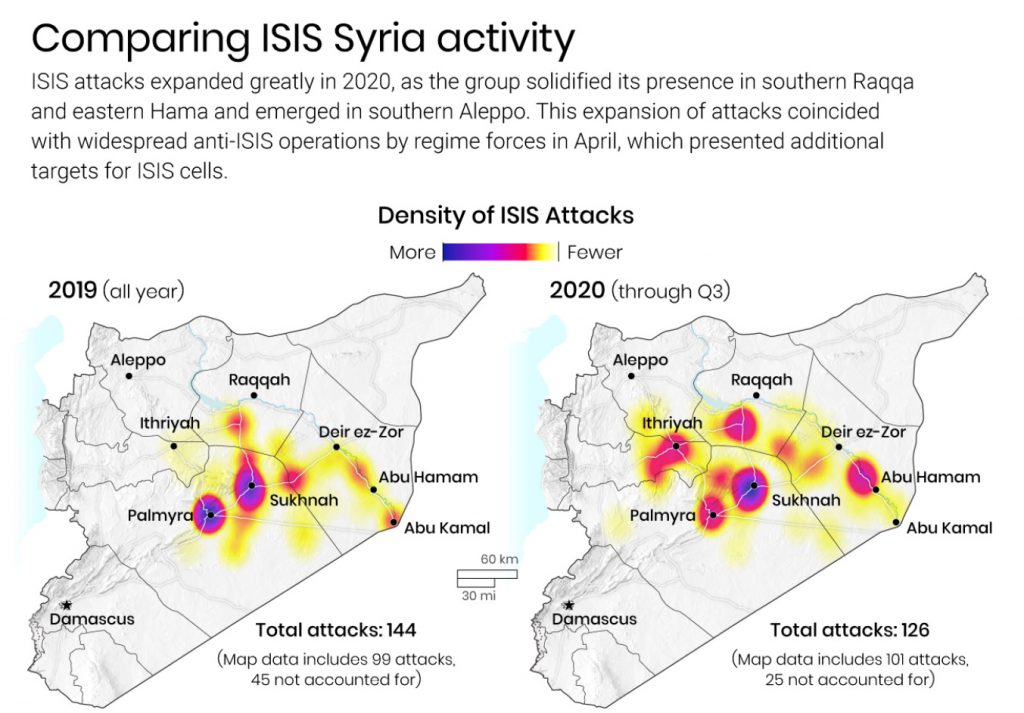

ISIS cells operating out of bases in the mountains north of Palmyra and Sukhnah, in the south Raqqah countryside, and in the cities and desert west of the Euphrates have grown in strength over the past year and a half, expanding the geographic reach and effectiveness of their attacks. These cells now control territory in central Syria, operating training camps in support of ISIS operations across the country. Since early 2020, Syrian regime forces have faced increasingly regular ISIS attacks outside of the traditional ISIS strongholds of east Homs and west Deir ez-Zor, with attacks now occurring in southern Raqqah, eastern Hamah, and southern Aleppo.

This report utilizes expert interviews as well as an exhaustive dataset of attacks and anti-ISIS operations gathered from public and private sources, with experts and participants on all sides of the conflict. All martyrdom data was collected from pro-regime public and private social media sources. Claims of regime losses from pro-opposition sources such as SOHR were not incorporated, and ISIS death claims were only used when footage of bodies was available. The attack dataset combines an assessment of the martyrdom data, pro-regime claims of ISIS attacks, ISIS attack claims, reviewed and confirmed data collected by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), and recurring interviews with Yusuf, a trusted assistant commander in the pro-regime National Defense Forces (NDF) recently deployed to the Badia. Enough ISIS claims in this region have been corroborated by pro-regime claims that the author feels confident in using the ISIS announcements for documenting attacks, if not for counting regime losses.

ISIS Attacks Since January 2019

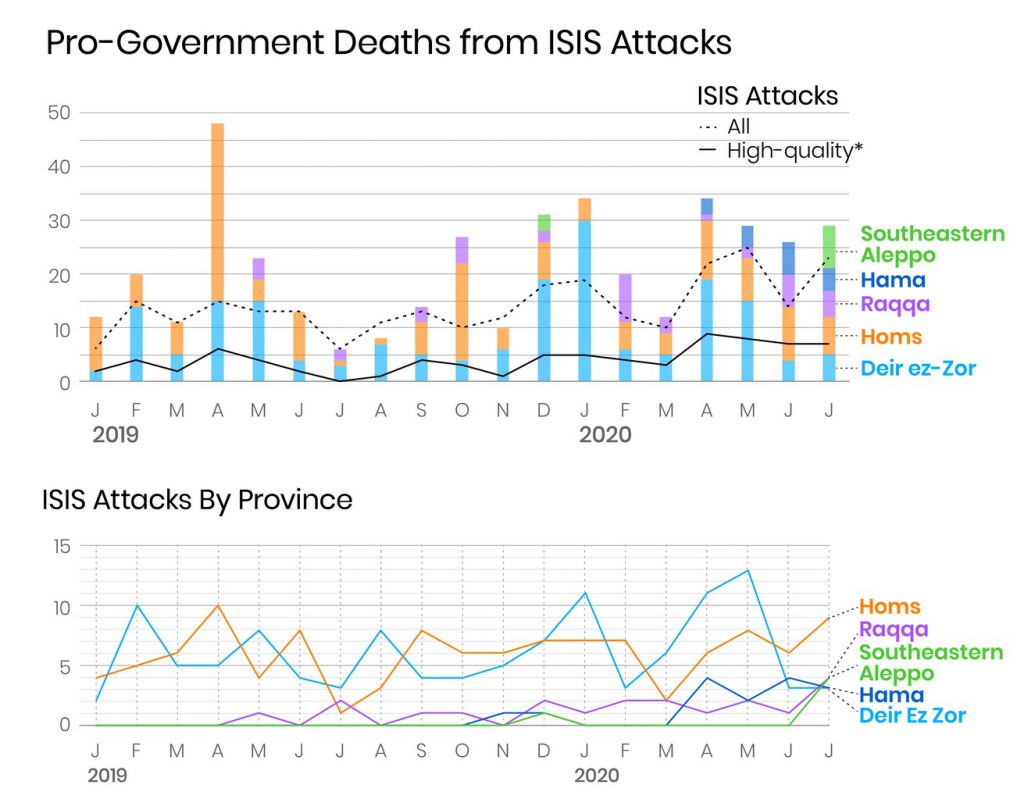

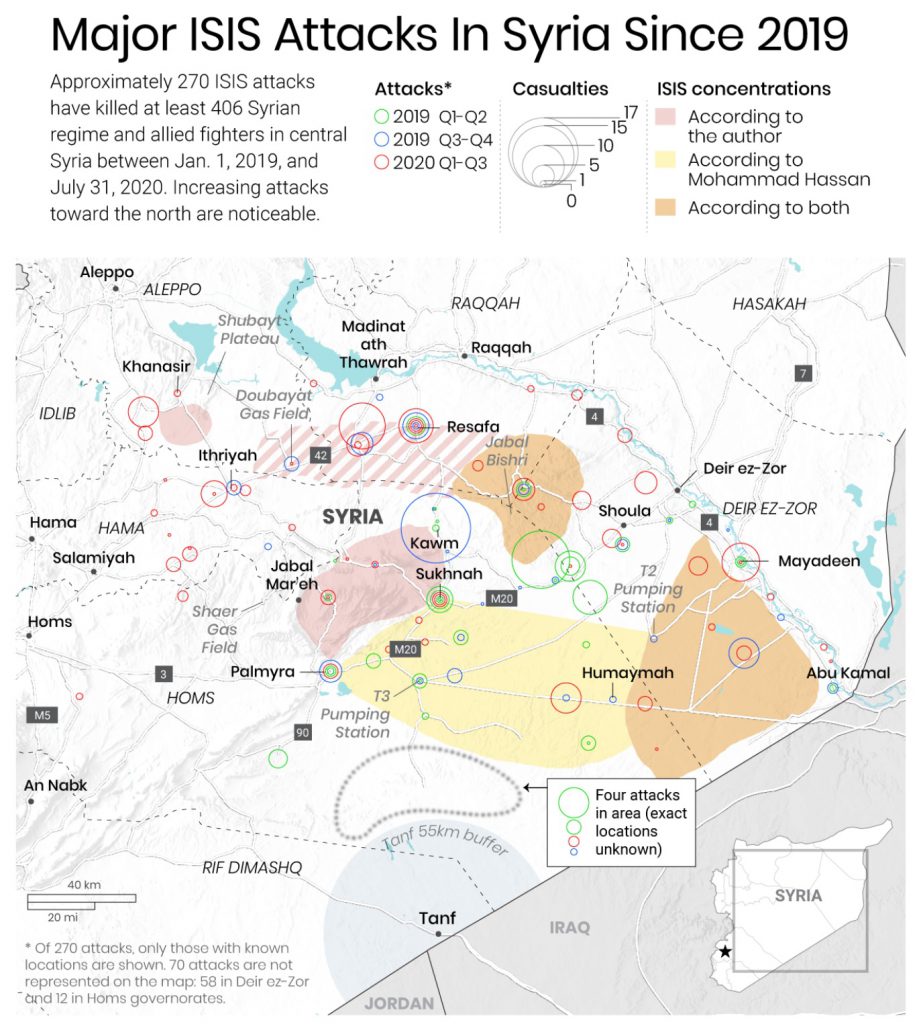

The author has documented 268 ISIS attacks that have killed at minimum 406 Syrian regime and allied fighters in central Syria between Jan. 1, 2019, and July 31, 2020. These attacks are coded by the province in which they occurred and whether or not they constitute a “high-quality” attack. An attack is considered high quality if it falls into one of six categories:

1. Attacks inside any urban area held by the regime or in “secure” regime areas

2. Attacks on checkpoints that left at least three reported dead, resulted in captured soldiers, or were part of larger coordinated attacks

3. Attacks that killed anyone of the rank of major or higher

4. Attacks that utilized fake checkpoints

5. Attacks using mines or improvised explosive devices (IEDs) that left at least three reported dead

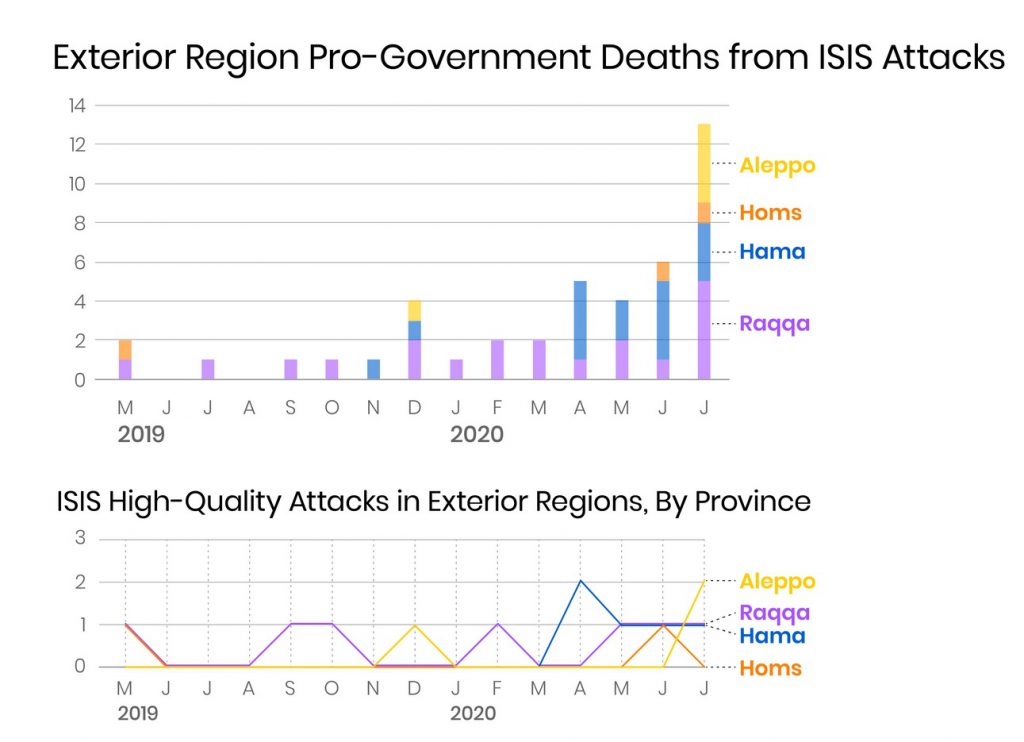

6. Attacks that used anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs)Modeled from the methodology employed by Michael Knights and Alex Mello in Iraq, distinguishing between high- and low-quality attacks allows for a more granular analysis of ISIS’s capabilities. Attacks with known locations have been mapped here. Most attacks in this period occurred in Homs (113 total attacks, 30 high-quality attacks) and Deir ez-Zor (115, 30) with steady and significant increases in both overall and high quality attacks in the “exterior” provinces of Raqqah (20, 8), Hamah (15, 5), and Aleppo (5, 3) since December 2019.

In April 2019, ISIS launched its biggest attack of the insurgency, ambushing a special forces battalion on the southern slope of Jebel Bishri and killing more than a dozen men including the battalion commander. ISIS fighters killed at least a dozen more soldiers in continuous fighting over the next two days, after which the regime decided to shift course and adopted a containment policy. Thus, ISIS was left in de facto control of Jebel Bishri while the region of al-Kawm became no-man’s land.

The drop in attacks following the battle likely reflects the fact that, as regime forces pulled back from core ISIS areas, cells had to go looking for targets. ISIS has used this time to solidify its core and expand geographically, conducting a string of attacks on the southern side of the Damascus-Deir ez-Zor highway from Shoula in Deir ez-Zor to the phosphate mines west of Palmyra. By the start of 2020, ISIS had further solidified its presence in south Raqqah. The large jump in documented ISIS attacks beginning in April 2020 coincides with new widespread anti-ISIS operations by regime forces. The scale of these anti-ISIS operations was unprecedented, ostensibly combing the entirety of the Badia over the next two and a half months. These operations presented many new targets for ISIS cells, as evident by the increase in mine and IED attacks, and the concurrent uptick in high-quality attacks proves that ISIS’s capabilities had increased by this time.

More worrying is the rapid geographic expansion of ISIS attacks over the past seven months. While ISIS had conducted a handful of attacks in east Hamah and south Raqqah prior to 2019, the expansion of attacks outside of its core region did not truly begin until December 2019, when attacks were conducted in all three exterior regions in the same month. High-quality attacks made up between one-third and one-half of all documented attacks in exterior regions, a much higher concentration than found in the core Badia areas, indicating that ISIS cells were able to effectively gather intelligence on regime force disposition in areas outside of its nominal control prior to launching attacks. Such examples include the April attack on the town of Rahjan near the Idlib border, the June attack that led to ISIS’s overnight seizure of two villages in east Hamah, and the August attack on the western side of the T4 oil pumping station in Homs.

The Structure of ISIS-Badia

It is unclear exactly how many ISIS fighters are operating in the Badia. In a series of interviews with the author, Syria expert Mohammad Hassan claimed that there are between 1,500 and 1,800 fighters, while commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) Gen. Mazloum Abdi said there are more than 1,000 and Yusuf, the NDF officer, estimated around 1,000. According to Yusuf, Syrian intelligence believes these fighters are organized into 15 to 20 active groups in Raqqah, Homs, and Deir ez-Zor, with approximately 70% of all fighters located in the urban belt along the western side of the Euphrates. Abdi agrees with this assessment.

The Badia insurgency is believed to be led by a former mid-level Syrian Arab Army (SAA) officer from Jobar, Damascus, who deserted in 2013. This man – whose real name is unknown, but he goes by the aliases Abu Abdallah, Sheikh Qaduli, Soleiman Rahman, and Dr. Rahman Zaid al-Shami – first joined the jihadist Green Battalion, formed by Saudi foreign fighters, before joining ISIS in 2014.

In a recent report, Hassan identified three main concentrations of fighters: southwest Deir ez-Zor, Jebel Bishri, and a swath of territory encompassing the entire eastern edge of Homs from Palmyra to Sukhnah to Tanf all the way to the T2 oil pumping station and Faydat Ibn Muaynah in western Deir ez-Zor. Based on an assessment of ISIS attack locations, the author believes a more precise third location is the mountains between Sukhnah, Palmyra, al-Kawm, and the Shaer Gas Field. According to Hassan, fighters move between these regions as needed.

The recent geographic expansion of ISIS attacks calls for identifying two additional core areas. South Raqqah attacks are almost certainly being carried out by cells permanently located in Raqqah province. The new spate of south Aleppo attacks have likewise been attributed by the regime to long-dormant cells in the Durayhim and Khanasir areas that merely waited for a drawdown of regime security forces before beginning their insurgency. East Hamah attacks, however, appear to be at least partially conducted by cells located in the mountains north of Palmyra.

While most of these fighters are locals with ample knowledge of the land and travel routes that avoid security forces, all interviewees mentioned the presence of foreign fighters as well.

ISIS attacks are carried out by groups of between three and 100 men, says Hassan, depending on need and target type. For example, on June 10 five ISIS fighters riding motorcycles ambushed and killed three regime soldiers northwest of Sukhnah, while on July 28 as many as 40 ISIS fighters attempted to raid a warehouse on the outskirts of Sukhnah.

ISIS appears to regularly mine roads commonly used by regime forces, as well as deploy IEDs for specific targets and assassinating regime officers. Other attacks are carried out with mixtures of small and heavy arms, utilizing technicals – pickup trucks mounted with heavy machine guns – for transport of personnel and harassing fire and motorcycles to quickly raid regime positions. ISIS has also released videos of at least two occasions in 2019 when it used ATGMs to target regime armor. Fighters can be equipped with more sophisticated weapons such as thermal optics, which regime units in this area typically lack, and their equipment generally resemble those used by ISIS cells in Anbar.

For its more complex attacks, ISIS has used captured flags and uniforms to set up fake checkpoints on the Damascus-Deir ez-Zor highway and has demonstrated considerable intelligence-gathering capabilities by successfully moving units around regime concentrations to strike deep into “secure” areas in central Homs and north and east Hamah. These tactics largely resemble those used in Iraq from 2009 to 2012, and likewise rely on support from local populations and heavy engagement with smugglers. According to Abdi, ISIS is also forcing major traders operating between central and northeast Syria to pay protection fees. According to Abdi, these fees are proportional to their monthly profits and average around $10,000 each month.

ISIS-Badia’s Relationship with Northeast Syria and Iraq

ISIS-Badia appears largely isolated and independent from neighboring ISIS insurgencies – with several important caveats. According to Abdi, in Deir ez-Zor men and supplies move both east and west across the Euphrates, with more movement east than west, in groups no larger than nine or 10, only bringing small and medium arms and explosives. This movement has been steady since the fall of Hajin, with the only “large group” moving across the Euphrates in late February 2020. There is even less movement in Raqqah province, where the SDF claims ISIS fighters cross the Euphrates individually, dressed as civilians. Movement there has increased since the coalition’s withdrawal from the area in late 2019.

This implies a certain degree of independence for the Badia insurgency from the rest of Syria. Indeed, when asked about the impact of the coalition’s successful killing and capturing of ISIS leaders along the Euphrates, Abdi said, “Leadership deaths are not impacting the insurgency in the Badia, as these cells are kind of independent.” As such, the final, brutal battles between ISIS and the Coalition on the eastern banks of the Euphrates in the first quarter of 2019 do not appear to have impacted the Badia insurgency.

Nevertheless, smuggling of people and weapons across the Euphrates continues, aided both directly and indirectly by regime forces. According to Abdi, ISIS cells along the Euphrates regularly pay regime commanders to “open” a portion of the river at night through which ISIS moves militants and supplies. The central role of regime commanders in cross-river smuggling underscores the ease with which ISIS cells can gather intelligence on regime officers – whom they have repeatedly assassinated – and highlights the regime’s inability to weaken ISIS.

This is further exemplified by the human smuggling networks ISIS utilizes to bring new recruits from northwest Syria to the Badia. Prior to Turkey’s Peace Spring Operation, ISIS movement from northwest Syria through northeast Syria was very limited, Abdi claimed. However, since the regime took over the main highways and crossings from north Aleppo down through Raqqah, ISIS has been able to bribe regime security forces in order to move new recruits back and forth. ISIS also uses these routes to transport foreign fighters who are smuggled in from Turkey by friendly groups in Idlib. Traders Abdi has spoken with claim that ISIS often has them wire their protection fees to accounts in Idlib, where the money is likely used to facilitate these smuggling operations.

According to Abdi, these new smuggling routes link into a series of mobile camps in the Badia where midlevel ISIS veterans train 10 to 40 recruits at a time. Most of the movement across the Euphrates is centered around these camps: New recruits from across the country travel in small groups to the Badia, receive training, and either return to their hometowns, enter northeast Syria, or remain in the Badia. Although concentrated near the border with Iraq, these camps are operated anywhere in the Badia that the regime is unable to properly patrol on foot. Abdi further stated that ISIS is now recruiting “at the individual level” across all of Syria, though most heavily from rebel-held northwest Syria and SDF- and Turkish-held areas in northeast Syria. Yusuf also claims that ISIS is employing forced recruitment of both locals and captured regime fighters.

While the presence of an antagonistic regime, Iranian, SDF, and coalition forces along the Euphrates has created a heavily militarized “border” between the Badia and northeast Syria, no such border exists between the Badia and Iraq. Numerous experts have written about the porous border along Anbar province, owing as much to the Iraqi government’s inability to properly patrol the region as to the Syrian regime’s lack of presence on its side. While most of ISIS’s supply needs are met locally, it is through Anbar that any major smuggling and trade routes exist.

Iraqi security forces began a major anti-ISIS operation in the first half of February 2020, which, according to an interview with Iraq expert Alex Mello, pushed “up to 150-200” ISIS fighters into the Syrian Badia before those fighters returned to Iraq a few months later. This assessment is supported by Yusuf, who claimed that there are “many Iraqi guys in the desert that have arrived” since February, and by Abdi, who in July said that “several months ago ISIS fighters moved from Iraq to Syria.” Furthermore, there was a spike in documented ISIS attacks in southeast Homs and southwest Deir ez-Zor in early April, supporting the idea that there was an influx of fighters in the area at the time.

Syrian Regime’s Anti-ISIS Strategy

The Syrian regime has failed to make any significant or long-term progress against ISIS in the Badia. The regime’s anti-ISIS strategy relies on convoys patrolling parts of the Badia, “clearing” empty hamlets and gas and oil installations before returning back to the units’ headquarters in nearby cities. Regime convoys overwhelmingly consist of technicals and small vans carrying soldiers. Some convoys include pickups mounted with larger weapons, such as anti-air cannons and artillery. None of these vehicles provide protection from rifle rounds, let alone the mines and IEDs that ISIS uses to harass the convoys.

The clearing operations can be small, driving through only a handful of points in a day. Other operations, particularly beginning in early 2020, have extended for more than a week and ostensibly cleared thousands of square kilometers. For example, between May 16 and June 21, Liwa al-Quds claimed to have conducted two anti-ISIS operations clearing 225 villages across 27,000 square kilometers (about 10,000 square miles) in Deir ez-Zor, Raqqah, Hamah, and Homs. As with ISIS cells in Iraq, cells in the Badia simply move or hide when these clearing operations approach and return to the area once the regime forces have left.

While pro-Iranian forces and Hezbollah are scattered across the Badia, it is not clear that these units conduct clearing operations in any significant manner. Similarly, Russian forces are concentrated in Palmyra, where they have somewhat successfully secured the city from ISIS attacks (only 26 of the 113 documented attacks in Homs are known to have occurred in the Palmyra area, with only seven of those occurring in 2020), and along the Euphrates, where Russian officers have been spotted overseeing regime operations.

Two shifts in the regime’s strategy occurred this year. First, according to Yusuf, Russian forces assisted regime forces in retaking Jebel Bishri in February. The mountain sits on the border of Deir ez-Zor, Raqqah, and Homs, overlooking the Damascus-Deir ez-Zor highway. This is the only time known to the author that Russian ground forces have conducted anti-ISIS operations outside of Palmyra. ISIS has since regained at least partial control over the mountain.

The second shift came in late March, when, according to Hassan, the regime and Iranian forces began building fortified outposts at 10 to 20 kilometer intervals near the towns on the western side of the Euphrates. This project coincided with an increase in attacks on regime positions in central and southern Deir ez-Zor, from a low of one in February to a high of 10 in May. It is around May that the regime adopted a policy wherein, as Yusuf told the author, “as long as ISIS doesn’t do anything [along the Euphrates], SAA won’t do anything.”

Abdi claimed that the regime now has “an indirect agreement … that ISIS does not attack towns along the Euphrates and SAA does not attack the desert in any serious way.” He went on to say that the regime has intentionally created an environment that supports ISIS movement into northeast Syria while simultaneously refusing to conduct any joint anti-ISIS operations with the SDF. Indeed, Yusuf claims that more ISIS fighters have recently moved from the Badia to the northeast. These claims match a dramatic drop in documented ISIS attacks – just five – along the Euphrates in June and July. However, the first half of August has seen a surge of Deir ez-Zor activity, with at least 21 regime fighters killed in three attacks north of Deir ez-Zor city and four in the desert north and west of Mayadeen.

Abdi argued that the regime’s inability to conduct any sustained or effective anti-ISIS operations is a result of its limited unmanned aerial vehicle capability and ineffective Russian close air support. Indeed, anti-ISIS operations rarely receive air support from either Syria or Russia, leaving soldiers unable to call in strikes on the rare occasion they do find ISIS militants. The fact that ISIS appears to openly travel in convoys of technicals throughout the Badia lends supports the claim that Syrian and Russian air assets are rarely employed effectively in this region.

Abdi further blamed manpower and equipment shortages for the regime’s over-reliance on infrequent patrols, an assessment shared by the author. Rather than divert resources to the Badia, the regime continues to mass its most effective units around Idlib and Latakia, and since October 2019 has been forced to divert more SAA and Republican Guard units to northeast Syria. Thus, much of the Badia operations have been left in the hands of militias, particularly regional NDF units and Liwa al-Quds, supported by several third-tier SAA units. Aside from being poorly trained and equipped, overreliance on militias – often recruited from locals – has opened the way for ISIS spies to infiltrate regime units.

Concluding Observations

The Syrian regime and its allies have proven themselves wholly incapable of handling the Badia insurgency. ISIS is successfully using central Syria to not only grow stronger locally but also to support regional operations with training bases. The Badia cells have demonstrated a high level of intelligence gathering and local knowledge, receive at least some local support, and have thus far managed to supply their operations almost entirely from local sources. ISIS will continue to expand north and west, seeking out regime weapon and supply stockpiles in east Hamah and south Aleppo. Meanwhile, the regime has turned a blind eye to ISIS activity along the Euphrates while the rampant corruption among its officers enables ISIS to further expand and entrench itself in this crucial region.

The Badia now serves as the bedrock of any future ISIS expansion in northeast Syria and Iraq. If the Coalition withdraws from northeast Syria, the currently militarized “border” along the Euphrates will fall, allowing ISIS fighters free access to the entire northeast. The Coalition cannot, and should not, operate in regime-held Syria, and thus its options to disrupt Badia cells are limited. Continuing anti-ISIS operations in northeast Syria and Iraq, as well as working to strengthen local security forces, will help to put pressure on the Badia insurgency. While these operations may only indirectly impact the Badia insurgency, the absence of Coalition forces and sustained anti-ISIS operations guarantees the rapid return of ISIS into the northeast.

In any scenario where the Syrian regime becomes the main anti-ISIS force in the region, ISIS will be able to accelerate its current strategy of establishing shadow control over its previous territories. ISIS may lack the resources for a full takeover, but its insurgency in the Badia proves the group continues to employ the strategic and technical prowess it demonstrated at it height.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News