Ankara’s intervention was paramount in turning the tide of the Libya conflict, bringing the 14-month assault on the capital launched by the self-styled Libyan National Army, Egypt’s primary ally, to a close in June. In July, in the middle of contentious tripartite negotiations over an Ethiopian mega-dam that would determine the future of transboundary riparian politics, Turkey invited a special representative to Ethiopia’s prime minister for a glitzy photo op in Ankara. And in recent weeks, simmering tensions in the eastern Mediterranean have erupted into a show of military force from countries both around the sea and farther away, including the United Arab Emirates and France.

For Cairo, something had to be done.

So, when Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry signaled to his Greek counterpart earlier this month that Cairo was ready to settle longstanding negotiations over a maritime border in the eastern Mediterranean, the containment of Turkey’s increasingly expansive foreign policy was at the forefront of his mind.

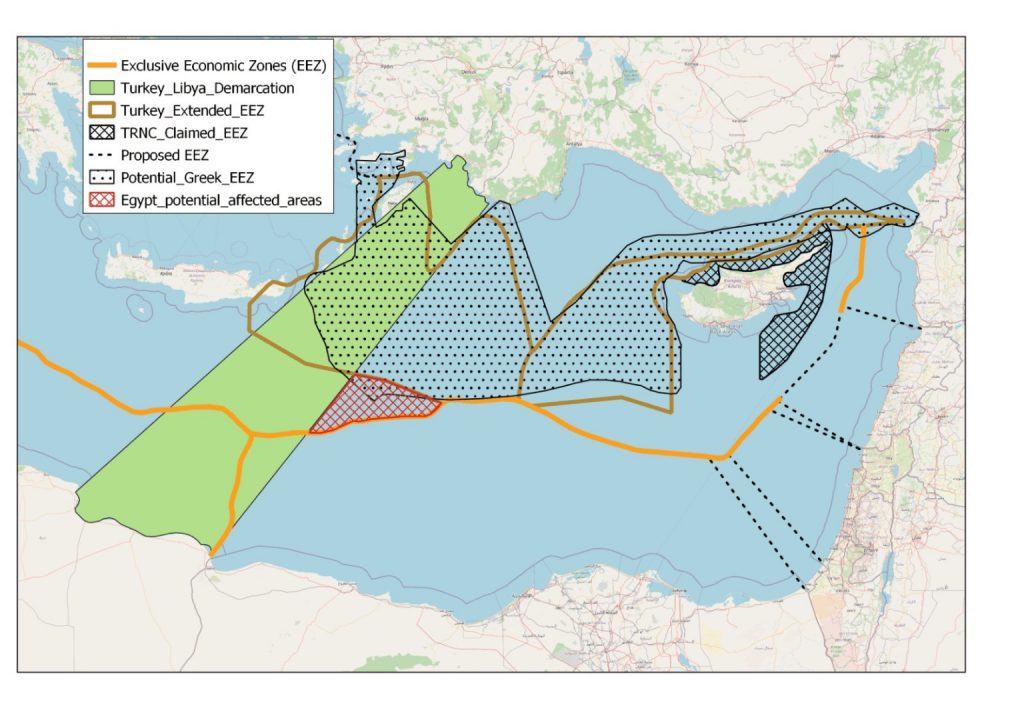

Speaking from the podium after the agreement was signed on August 6, Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias hailed the deal with Egypt as “exemplary,” underlining the deal’s anti-Turkish character by saying “it is the complete opposite of illegal, invalid and legally non-existent.” Dendias was referencing the memorandum of understanding that Turkey and the Libyan Government of National Accord signed at the close of last year that linked Turkey’s coastline to the north coast of Libya, cutting through a contested waterway where a major pipeline that would bring the region’s hydrocarbons to Europe was planned to be constructed.

The Greek minister’s combative tone was in lockstep with the calls in Egypt for a military intervention in Libya that had dominated the airwaves in the weeks prior as rumors of an imminent push by Turkish-backed forces into eastern Libya circulated. And while Egyptian military intervention faced several significant hurdles to sending troops across its western border, Egypt engaged in a diplomatic fight, even at a potentially steep cost.

The deal gives Egypt and Greece — rather than Turkey — the ability to allocate exploration blocks to American companies, especially after the US company Chevron entered the Mediterranean basin through its acquisition of Noble Energy and Gas last month. However, it came at the expense of Egypt forfeiting areas that have yet to be tapped in order to deal a blow to Turkish influence, a fact that some on Egypt’s negotiating team felt was too great a concession, according to a consultant familiar with the negotiations.

Turkey, which maintains economic ties to Egypt despite ideological differences over the role of political Islam in the region, had repeatedly stressed this point to Egypt, according to three Egyptian officials close to the negotiations.

“Until the very last minute, Turkey kept sending us direct messages, suggesting that we should not sign a deal with Greece and start by signing a deal with Libya because that would give us more water,” says one of the Egyptian officials. “It is true that this could have given us more water, but it would have meant that we would have had to be playing with and not against Turkey in the Mediterranean, and this is something we are not doing.”

In order to close the deal, it was necessary for “the intervention of the political leadership on both sides,” according to a Greek official who spoke to Mada Masr.

The calculus behind the Greek-Egypt maritime agreement shines a light on Egypt’s foreign policy toward Turkey more broadly. Rather than an unequivocally anti-Turkish stance, which could lead to dangerous military brinkmanship, officials in Cairo have often been in talks with their counterparts in Turkey. The discussions include both the demarcation of maritime borders as both sides vie for a role in the East Mediterranean’s energy future and to ensure the two sides do not clash directly in Libya, according to several Egyptian officials. Egypt continues to try to keep Turkey’s ambitions to bring about a new regional power balance and security architecture in check, while acknowledging that Ankara will necessarily play a role in divvying up influence and economic spoils.

Divvying up the East Med and deconstructing the status quo

“The Egyptian-Greek Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) deal is important because it settles, at least partly, an issue that has been open for decades in the area and completes another small puzzle in the maritime zone disputes of the Eastern Mediterranean,” says Zenonas Tziarras, a researcher at the PRIO Cyprus Centre, an independent, bi-communal research center located in Cyprus.

For Turkish officials, however, the matter is far from settled.

Immediately after the deal was inked in Cairo, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu slammed the agreement.

“We’ll continue to show them and the world that this agreement is null and void at the table and in the field,” Cavusoglu told the Turkish state-owned Anadolu Agency on August 6.

Cavusoglu was backed up by comments from Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan later the same day. Calling the agreement “worthless,” Erdogan told reporters that Turkey “has started drilling work again,” jettisoning Germany’s July push to halt Turkey’s probes and bring the two sides together for bilateral talks.

In the intervening weeks, Turkey issued several international maritime alerts (or Navtexs), declaring that it would deploy seismic research vessels flanked by warships along the southern coast of the Republic of Cyprus, the Greek island of Kastellorizo that sits just off the coast of Turkey, and an area close to Egypt’s maritime border.

The Hellenic Navy in turn has shadowed the Turkish fleet. At one tense point, Greek ships broadcast a message every 15 minutes for 12 hours asking the Turkish vessels to leave, and at another, warships from the two sides collided. The Greek ships were soon joined by two French Rafale fighter jets and the naval frigate Lafayette. On August 21, officials in Athens said that the United Arab Emirates would send warplanes to the southern Greek island of Crete for joint training with Greece’s air force.

According to Tziarras, such moves by Turkey — the publication of a Navtex, the announcement and conduct of natural resource surveys and illegal drillings, such as in Cyprus’s EEZ, and the Turkey-Tripoli EEZ deal — “are part of Ankara’s efforts to deconstruct the existing regional status quo and security architecture and bring about a new one that will be more beneficial to itself, in terms of the geopolitical space, the natural resources and the maritime routes that it will be able to control.”

“At the same time,” Tziarras says, “creating a geopolitical fait accompli is Turkey’s way of setting the bar high so that it is later able to negotiate various issues from an advantageous and powerful position.”

Despite the continued potential for tensions on the high seas to spill over, a European official based in Cairo tells Mada Masr that Turkey’s escalatory tactics have won it the audience of Germany, which is offering Turkey a deal that would include mediation from Berlin between Ankara on one hand and Athens and Nicosia on the other. “The Turks have not rejected the offer out of hand,” the official says, adding that the impression based on meetings that have taken place in recent weeks is that Turkish officials are willing to strike a deal.

And Egypt is also not done negotiating over the contested waters where Turkey is projecting influence.

On August 18, Egypt’s Parliament gave the go-ahead to what the state-owned MENA news agency called the “partial demarcation of the sea boundaries between” Greece and Egypt, noting that “the remaining demarcation would be achieved through consultations.”

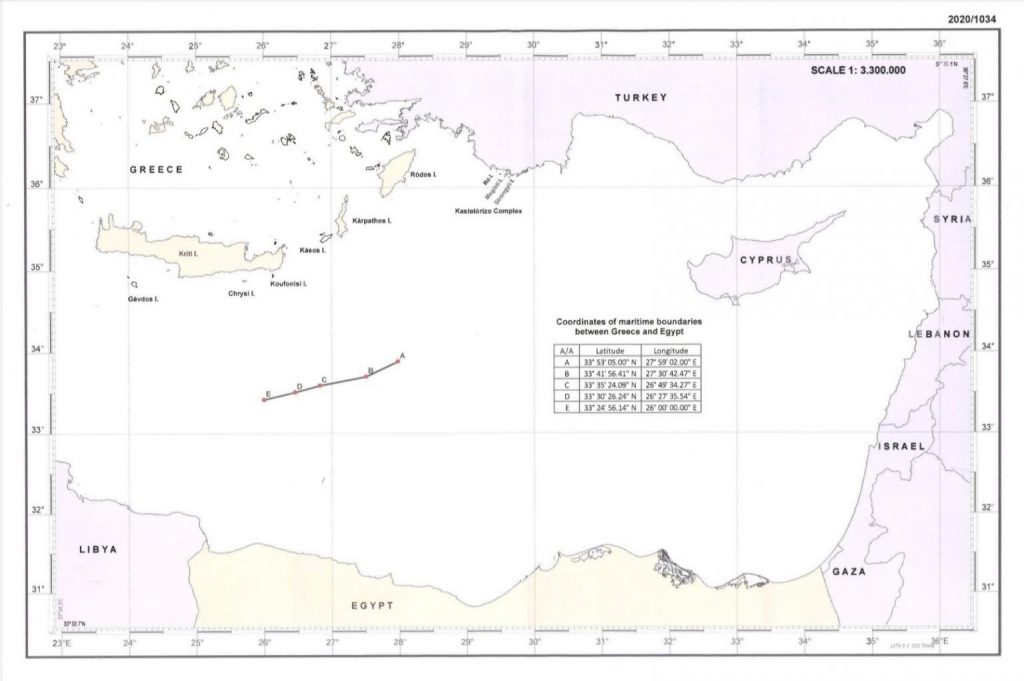

In a map sent to Reuters following the agreement, the “partial demarcation line” can be seen, effectively blocking the Turkey-GNA agreement signed last year which cuts through a waterway under which the planned EastMed pipeline would be constructed.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a state’s exclusive economic zone extends 200 nautical miles (370 km) out from its coastal baseline. The exception to this rule occurs when EEZs overlap: that is, when state coastal baselines are less than 400 nautical miles apart. When an overlap occurs, it is up to the states to delineate the actual boundary.

Turkey, however, is not a party to the UN convention, and it has contested that the islands of Rhodes and Crete are not entitled to EEZs. It also argues that the EEZ granted to the island of Kastellorizo, positioned close to Turkey’s coastline, should be limited, as granting it an EEZ would greatly reduce Turkey’s maritime territory reach into the Mediterranean.

Based on the map obtained by Reuters, the Greek-Egyptian maritime agreement only applies to the islands of Crete and Rhodes, leaving the question of what will be decided with Kastellorizo up in the air.

Elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean, Turkey — which has aspirations to fashion itself into an energy hub despite the possibility that it could be bypassed completely by the EastMed gas pipeline running from Israel to Crete and then onto southern Europe through Greece — has been actively trying to gain a better foothold with Israel and in the EastMed Gas Forum.

These moves might be largely symbolic right now, as the onset of the coronavirus pandemic has stymied the gas export market to Europe. According to a second European official from the same country, the price of natural gas is currently not conducive to the execution of any mega projects. This would apply both to the US$8 billion EastMed pipeline, running from Israel to Crete and then onto southern Europe through Greece, and Egypt’s US$1 billion contingency plan of getting Cyprus to establish a pipeline to Israel so that the gas of both Cyprus and Israel will come through Egypt, where it would be managed in Shell’s EDCO refinery.

However, Walid Khadduri, an independent oil and gas expert, says that the EastMed gas pipeline was not feasible even before the current economic downturn.

“If you look at the plan, there is huge seismic activity, especially off the coast of Greece. This is not possible, not feasible. The cost is too high. Even the European Commission published reports that this project is not feasible but because of political reasons they act like it is feasible. The biggest chance for the project to get done, especially for Israel, is through Turkey,” Khadduri says.

According to a Turkish energy consultant in the private sector familiar with the government’s energy policy, there have been long-standing discussions about just such a pipeline between Turkey and Israel that would transport Israeli gas to Europe.

“Those negotiations have never stopped. Business between Israel and Turkey has never stopped. The Turkish presidential palace and Erdoğan’s inner circles have never cut their relations with Israel. Maybe he was shouting publicly at Israel, criticizing Israel over the Mavi Marmara incident, but second and third channel communications have never ceased to exist,” says the energy consultant, who met with an Israeli delegation last year to discuss the pipeline plans but criticized the steep terms of the proposal as a push to normalize Turkish–Israeli relations.

Despite the seeming ideological differences between the two sides, a former Turkish naval officer says that US intervention and turnover in Israel’s new government could resolve the disputes. “The new foreign minister of Israel is someone that could be collaborated with, unlike Lieberman,” the officer says. “With the new government, I have hope that relations can be mended. This can be done behind closed doors or with back-channel diplomacy. Diplomatic relations can be normalized, but to get a result in Turkish–Israeli relations, Washington must be involved.”

A high-ranking former Turkish diplomat and several European diplomats say the US has been actively trying to mediate the broader dispute in the Mediterranean. According to the diplomat and officials, the US is very much in favor of Turkey joining the EastMed Gas Forum — the body formed for gas coordination in January 2020 that includes Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan and Palestine — for three reasons. First, it would make the investment of American oil and gas companies more profitable. Second, the US is in favor of brokering a solution in the conflict between Turkey and Greece because it shakes the solidarity within NATO. Third, the US would like to resolve the Cyprus problem and sees closer Greek-Turkish coordination on gas as a positive step in that direction.

Egypt has invested significant political capital into securing an import deal with Israel that would be a first step in fashioning itself into a regional energy hub. Under the deal, Egypt began importing natural gas from Israel that Egypt would then export through its existing LNG shipment facilities.

All three Turkish sources stressed the need for a pragmatic foreign policy, despite ideological differences with some of their interlocutors, including Israel and Egypt, a fact Tziarras notes stands next to the roots and a significant component of the present-day articulation of the AKP’s foreign policy as anti-Western, anti-Semitic and with an Islamist agenda.

“It is impossible for a country that wants to become a great power — like Turkey does — to do so without trying to maximize its national power components (e.g. its economy, military might and access to natural resources) and its influence abroad,” Tziarras says. “In that sense, there is, indeed, a strong pragmatic aspect in Turkish foreign policy that is, however, part of greater geopolitical strategy. The Turkish business sector (including business associations, be they conservative or secular) always tend to be more pragmatic in their approach, pushing for good relations with both the West and the East. This manifested in Turkey’s relations with Israel and Egypt, as well, where despite political problems economic relations were not interrupted. From this perspective, it seems that Turkey managed to compartmentalize its political and economic relations with these (and other) countries.”

Nonetheless, Tziarras argues, energy cooperation, especially pipeline connections, are a different story. “History and research shows that political relations need to be somewhat normalized before something like that takes place,” he says. “While it is not unlikely for Turkey to restore relations with Israel and Egypt in the future, it is possible that Erdogan will need to reproduce the crises with these countries for domestic consumption, as part of [his] efforts to remain in power at least until 2023.”

A contest for influence in Africa

For Tziarras, there is also an important link between Turkey’s push for control over natural resources in the eastern Mediterranean and its intervention in Libya.

“Turkey is now looking to acquire a permanent military presence (as well as political and economic influence) in Libya that it will use to further expand its sphere of influence into Africa. An important aspect of this strategy is natural resources,” he says, pointing to the fact that the Turkish Petroleum Corporation has applied to Tripoli for exploration permits in its maritime space.

Well aware of the strategic importance a foothold in Libya could provide, Egypt has opened channels with Morocco and Algeria, intent on weakening Turkey’s influence, according to two Egyptian officials.

However, the center of Egypt’s effort is focused on talks around the political future of Libya.

Over the weekend, the Turkish-backed and United Nations-recognized Government of National Accord and the House of Representatives, the parliamentary body that has provided political backing to the LNA, released statements in parallel announcing a ceasefire.

According to Egyptian and foreign diplomatic sources, the ceasefire, which comes after the relative sidelining of Khalifa Haftar after the Libyan National Army’s 14-month bid to seize the capital of Tripoli failed in June, materialized through the joint negotiation efforts of a number of countries concerned with the ongoing Libyan conflict. Russia held simultaneously diplomatic negotiations with Turkey and talks with Cairo. This occurred in parallel to American-Turkish and American-French talks, with Germany mediating between the warring parties.

According to a source familiar with Moscow’s diplomatic moves, Russia was able to persuade the GNA and its backers in Turkey and Qatar as well as House of Representatives Speaker Aguilah Saleh and his supporters in Cairo and Paris to accept an arrangement that would include an immediate halt in the movement of GNA forces to the west of Sirte and Jufrah, and LNA forces to the east, with plans to establish a demilitarized zone along the Jufrah-Sirte red line.

The source adds that Russia is working on drafting a political roadmap for the future of Libya in coordination with the countries concerned regionally and internationally, including Egypt and Algeria, and Germany. This roadmap, the source says, is based on the election of a new presidential council, which would not include Serraj, and a restructuring of the LNA, at the top of which will sit a military council that will not include Khalifa Haftar.

For the same Egyptian official, who has been briefed on this roadmap, Cairo hopes that the potential military council and new presidential council, which could materialize as soon as next year, will limit Turkey’s influence. In recent discussions concerning Libya, Shoukry and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo have agreed that Turkey cannot be a “kingmaker in Libya,” the official says.

In order to actualize this aim, however, Egypt must work against a long-entrenched dynamic between Turkey and two of its own allies in Russia and the US.

“The ideological vision of Turkish foreign policy under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) was assisted by structural changes in the international system, most notably the regional power vacuums created from the mid-2000s onward when the Iraq War and the gradual retreat of the United States from the area created new security concerns and opportunities for Turkey,” says Tziarras. “Over the past 10 years Turkey has transformed into a full-blown revisionist power. And partly because of the limited US involvement in the region, Turkey has also been able to redefine its relationship with the US and Russia and turn it into a largely transactional one. As such, over the past five years or so, Turkey emerged as a ‘third pole’ in the broader Middle East, i.e. between the US and NATO on one hand and Russia on the other, trying to benefit from the best of both worlds, not always successfully. In this context, the US and NATO found themselves in a historic dilemma: to ‘discipline’ Turkey and risk pushing it further to the arms of Russia and Eurasia, or incentivize it (sometimes using a carrot-and-stick approach) in order to keep it close to the West? It seems that Washington has so far opted, for the most part, for the latter and, as a result, it often ended up turning a blind eye to Turkish revisionism, either in the Middle East or the Eastern Mediterranean. Not least because Turkey appears willing to occasionally accommodate or serve certain NATO interests, e.g. in Syria, Libya or the Black Sea.”

Plunged in the middle of the Eastern Mediterranean crisis, Turkey appears content to continue probing this arrangement. On Sunday, Sergey Chemezov, the head of the Russian state conglomerate Rostec, which manages mostly defense and high-tech companies, said that Russia is likely to sign a contract for the delivery of an additional batch of S-400 missile systems to Turkey next year. Turkey bought a batch of the missile systems from Russia last year, leading to its suspension by the US from the F-35 stealth fighter jet program. The United States has said that Turkey risks US sanctions if it deploys the Russian-made S-400s, according to Reuters.

Beyond Libya, Turkey’s foray into Africa is reflected in several other diplomatic moves this year, including a military cooperation agreement it signed with Libya’s southern neighbor Niger at the end of July. And earlier this year, Erdogan continued his push to extend Turkish influence in the Horn of Africa to counter Gulf rivals like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, announcing on Turkish state television that Somalia, whom Turkey has long provided aid, had invited Ankara to explore for oil in its seas.

And Somalia is not the only country in the Horn of Africa which Turkey has set its sights on. In recent months, Turkey has tried to take advantage of the contentious negotiations around the Grand Renaissance Ethiopia Dam to gain a foothold in Ethiopia.

This effort was most visible on July 17, when the Turkish foreign minister hosted Mulatu Teshome Wirtu, Ethiopia’s former president and the special representative to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

“After Sisi came to power, we have been looking to balance Egypt’s influence. We do it in Libya and also in East Africa,” says a consultant for the Turkish Foreign Ministry’s Africa policy, who spoke to Mada Masr after the July meeting. “When we look at how we can counterbalance Egypt, which actors are there? There is Ethiopia. Ethiopia has been excluded from the 1929 and 1969 agreements about the Nile but recently it has emerged as an influential new actor in the region. Therefore, us developing our relations with Ethiopia is a direct answer to Egypt. There are two dimensions. We want to develop our relations with Ethiopia, and we want to develop our relations with an Ethiopia that is stronger against Egypt. A strong Ethiopia against Egypt is something that Turkey wants.”

A Turkish government official told Mada Masr that Ankara was aiming to secure arms deals from Addis Ababa, which the consultant corroborated. “Maybe it will not be a buyer like Somalia, but after the July visit, there we will be reflections on the military side as well. We will establish trade and cultural relations, but at some point they will evolve into economic and military relations,” the consultant says.

Speaking during a webinar on August 23, Egypt’s former Ambassador to Turkey Abderahman Salaheldin pined nostalgically for a return to a Turkish foreign policy defined by “zero problems with anyone.”

“In the eastern Mediterranean, [Erdogan] is not supported by a single country, not in the region and not all over the world. I think he has come to recognize that, and I think he has come to realize that the role of the ‘spoiler’ will not be tolerated by many. I am one of those who still believes that he might be able to come back to his earlier pragmatism,” said Salaheldin. “I have seen him following for 10 years this model that was admired by everyone. And I think it is still possible. And if he does, I can assure you of one thing: he will find open doors in Egypt.”

However, a return to the political pragmatism of the past may be outside the realm of possibility until a new regional power arrangement takes form. New doors are being opened, and both Egypt and Turkey are trying to walk through them.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News