Shairbek Dzhuraev, Crossroads Central Asia

Peace is on the brink in Central Asia. The border conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan has reached a new bottom. The clashes of the past week left at least 40-50 people killed, mostly civilians. More than a hundred houses were burned, and remnants of good neighborly relations in the region were shattered. Clashes involving stones and guns have lately become regular events. However, the main “novelty” of the conflict is apparent: an unprovoked military attack against civilians and occupation of villages of a neighboring state. The Tajik military set a precedent that revealed the new depths of insecurity in the region.

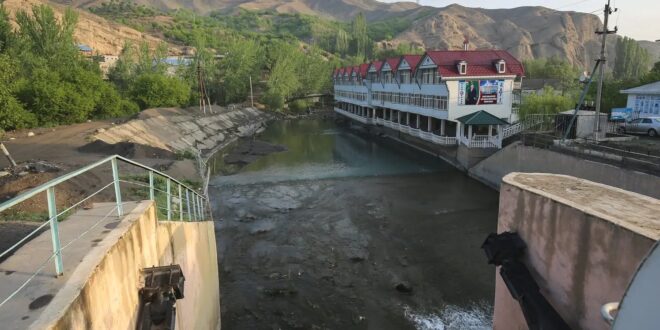

The conflict started on 28 April at the Golovnoi water supply facility. The latter is a critical piece of infrastructure distributing water to irrigation canals of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. While Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have numerous disputes over the border in the region, Kyrgyzstan’s ownership of the Golovnoi water facility had not been contested in the past. On 28 April 2021, the local government of Tajikistan’s Isfara district installed cameras on an electric pole at the water supply facility. Residents of Kyrgyzstan’s villages protested, with crowds exchanging stones. Governors’ talks did not help, and on 29 April, residents clashed again. Troops engaged on both sides, leaving scores of soldiers and civilians dead. Border posts and houses in the adjacent area came under gunfire while the two governments accused each other of shooting first… Read More @ Crossroads Central Asia

Eric McGlinchey, George Mason University

Conflict along Central Asian state borders is not new. Critical infrastructure, ethnic groups, and entire villages straddle the poorly demarcated and often convoluted borders Central Asian states inherited as a result of the Soviet collapse. And to make things even more complicated, exclaves pepper the border regions of the Fergana Valley. Three Uzbek and two Tajik exclaves are in Kyrgyzstan, and one of the sites of conflict during the April 28-29 violence was along the road that leads to the Tajik exclave, Vorukh.

Although conflict along Central Asian state borders is not new, what is unusual is the scale of the late April violence and the weaponry used in this violence. While past conflicts have seen an escalation from stone-throwing to guns, the late April conflict appears to be the first incidence with sustained automatic weapon gunfire. The Kyrgyz state news agency Kabar claims that Tajik security forces were behind the machine gunshots.

Among the many questions surrounding this recent round of violence is why the escalation? Why did the violence reach this heightened level? The typical reasons cited for cross-border violence are insufficient to explain this heightened conflict. Yes, messy borders are proximate causes for conflict. Yes, disputes over natural resources—grazing land and, most notably, water—are proximate causes for conflict. These causes, though, are constants in Tajik-Kyrgyz relations. These causes cannot explain the aberrant scale of the late April Kyrgyz-Tajik border violence.

What may explain the uptick in violence is the possibility that the Tajik state feels newly emboldened. The sources of Tajik state confidence vis-a-vis Kyrgyzstan are two-fold. First, the Kyrgyz state is weak, perhaps weaker than it has ever been. Kyrgyzstan’s new president, Sadyr Japarov, was in prison nine months ago. His meteoric rise from prison to the presidency is viewed as suspect in the eyes of many Kyrgyz. And, not surprisingly, Japarov has initiated a campaign of intimidation in an attempt to silence voices critical of his regime. There has been a marked uptick in state and non-state actors’ intimidation of independent journalists, civil society activists, and academics in recent months. Tajik President Emomali Rahmon, no stranger himself to oppositionist challenges, understands well that Japarov’s response is a sign of the Kyrgyz regime’s weakness, not strength.

Second, Rahmon may feel emboldened by the recent large-scale military exercises Tajikistan held with Russia earlier in April. While Kyrgyzstan does have cooperative military relations with Moscow—Kyrgyzstan is home to Russia’s Kant Airbase—Kyrgyzstan has never engaged in mass-scale military maneuvers like the 50,000 troop strong exercises Moscow and Dushanbe jointly conducted in Tajikistan between April 19 and 23. This combination of the Tajik state’s recent show of military force with Russia and the Kyrgyz regime’s embattled domestic legitimacy may well be deeper, albeit less visible drivers of the unusually deadly late April violence on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border.

Lawrence P. Markowitz, Rowan University

This is already a complicated situation that involves a number of moving parts such as politicians, border control, local officials, other security agencies, local populations in the disputed regions, and considerable rhetoric in social media.

There are indications that contentious (or at least questionable) political statements between local (and national) politicians in both countries about this area preceded the fighting. Smaller-scale incidents and provocative actions (flexing of military muscle) in these areas also occurred in the past few weeks. The incident itself begun as a specific dispute (over the installation of CCTV cameras) involving workers from Tajikistan and objections from Kyrgyzstani local officials and border control. Reports suggest that the fighting has included several other security agencies that were mobilized. The conflict has generated jingoistic statements in social media (by local leaders and everyday people as well).

There have been incidents on borders in the past that involved a local altercation or a smaller dispute. This incident seems a little more complicated—both because of the extent of the conflict itself and because both regimes lack wide public support domestically and may see political benefits from making assertions of sovereignty.

Edward Schatz, University of Toronto

Many deadly factors have come into play here—including resource scarcity, uncertainty over a complex and contested frontier, and remoteness from the power of the central state. What should not be lost in the analytic shuffle is the changing configuration of international forces. A decisive shift away from norms based on commonly held and stabilizing rules of cooperation makes this a particularly precarious moment.

In Tajikistan, the Rakhmon regime continues to deepen its economic ties to China and military ties to Russia, all the while consolidating an authoritarian system based on impunity toward political opponents. While we do not yet know the actual motivations of the regime in this deadly dispute, it is worth highlighting that both China and Russia have in the past decade blatantly and unapologetically violated crucial international norms (norms about human rights and norms about territorial integrity and sovereignty). This is the water in which Tajikistan now swims.

For its part, Kyrgyzstan has recently witnessed the rapid rise of an initially marginal political figure (Sadyr Japarov) from prison to the country’s presidency. How this occurred is a complicated story, but ties to organized criminal networks appear to have been crucial. Here too, the currency of politics is impunity. Japarov has recently rammed through major constitutional change, running roughshod over his country’s international obligations and domestic legal requirements. In addition, his regime has capitalized on widespread, rising ethnonationalist sentiment and ignored calls for the protection of ethnic and sexual minorities. This is the water in which Kyrgyzstan now swims.

When acting with impunity, moving swiftly to establish faits accomplis, and violating norms of cooperation are normalized, it takes little to generate destabilizing and deadly outcomes.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News