The diplomatic row between China and Bangladesh that ensued last week highlights China’s fears about the potential of a “Quad Plus.”

The Quad worries China and may explain why Beijing has forcefully attempted to dissuade other Asian states from joining the budding alliance.

Bangladesh’s geostrategic position in Asia makes the prospects of Dhaka joining the “Quad Plus” a thorn in China’s side.

The situation in Bangladesh is a microcosm of some of the Biden administration’s most significant challenges in the Indo-Pacific region.

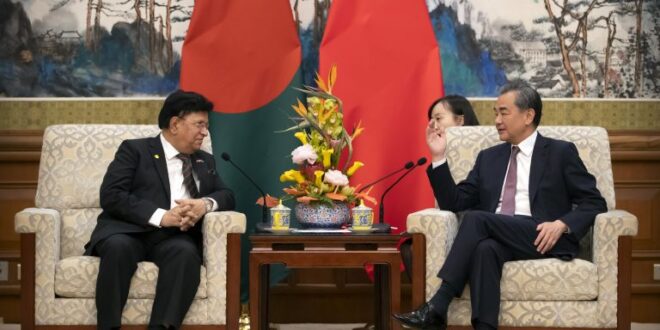

The diplomatic row between China and Bangladesh that ensued last week highlights China’s fears about the potential of a “Quad Plus.” On May 10, China’s ambassador to Bangladesh, Li Jiming, warned that if Bangladesh sought to join the Quad — an informal multilateral forum comprised of the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia that China perceives as an attempt to contain its ability to project power in Asia — the relationship between the two countries would suffer “substantial damage.” Bangladesh’s foreign minister, A. K. Abdul Momen, hit back the next day, criticizing China for infringing on Bangladesh’s sovereignty and right to determine its own foreign policy. At the same time, Momen also affirmed that Bangladesh had not been approached by any of the Quad member states with a proposal for joining the group. Apart from the episode highlighting China’s increasingly aggressive diplomatic tone, dubbed “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy” it also signals China’s growing discomfort regarding an expansion of Quad membership to other Asian countries, which would infringe on its perceived geopolitical sphere of influence.

Beijing’s fears are not necessarily unfounded. After its establishment in 2007, the Quad was long a dormant multilateral dialogue forum, but since 2017 has become more active — a trend that has continued under the Biden administration. While the Quad, unlike NATO, is not a formal security alliance, Quad members have conducted joint military exercises in the Indo-Pacific, issued a joint statement, and are planning an in-person meeting on the sidelines of the G7 summit in June. While China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi famously dismissed it as “sea foam” in 2018, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials and Chinese state-backed media have become more vocal in criticizing the Quad. They accuse it of being an “anti-China alliance” that “trumpet[s] the Cold War mentality” and aims to contain Beijing. While the group asserts its primary interest to be “a shared vision for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” analysts generally agree that the Quad has been invigorated due to Xi Jinping’s increasingly aggressive foreign policy. Moreover, the March 20 COVID-19 Quad meeting, which also included officials from South Korea, Vietnam, and New Zealand, signaled that the grouping may look to expand its membership by forming a “Quad Plus.” This prospect worries China and may explain why Beijing has forcefully attempted to preemptively dissuade strategically important Asian states from making such a move.

Bangladesh’s geostrategic position in Asia makes the prospect of Dhaka joining the “Quad Plus” a thorn in China’s side. The country is not only located close to the Bay of Bengal — a key trade route which was also the place for a recent joint Quad naval exercise — but is also a recipient country of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Bangladesh maintains strong relationships with many of the Quad members, and they will likely be wary of placing Dhaka in a difficult position. Moreover, Dhaka has close ties with India and will be sensitive to the concerns of its close regional partners; the Bangladeshi government will be reluctant to become enmeshed in a potential conflict which risks compromising its key regional relationships. China’s threat to Bangladesh came at an opportune moment. As neighboring India is struggling with a devastating COVID-19 outbreak and has placed a pause on vaccine exports, Beijing gifted 500,000 doses to Bangladesh on May 12. While the Quad members promised to deliver a billion vaccine doses to developing countries in the Indo-Pacific by the end of 2022, few details about the undertaking have been shared since the announcement in March, leaving the door open for China to pursue its aggressive “vaccine diplomacy” in the region. China is also an important actor in resolving tensions between Bangladesh and Myanmar, including the longstanding issue of ensuring a safe and secure future for the Rohingya.

Only the future will tell how muscular the Quad grouping may actually be in terms of security issues; if it will eventually become a formalized alliance; and if the “Quad Plus” will ultimately materialize. The possibility of a “Quad Plus” may become more tangible following Biden’s recent summit with his South Korean counterpart in Washington last week, where Biden and South Korean President Moon Jae-in discussed various steps to forge a closer partnership in order to compete with China. The situation in Bangladesh, however, is illustrative of the Biden administration’s challenge in the Indo-Pacific. Thus far, Biden has continued much of the policy vis-à-vis China developed under Trump, with the added element of engaging allies and partners. While facing domestic pressure to be tough on China, Biden also has to ensure that his foreign policy does not antagonize the CCP to the point where it destabilizes the region and leads to issues for allies and partners. Many regional countries still perceive the idea of “choosing” between the U.S. and China as counterproductive, and Washington should take that into consideration when designing the future of the Quad and the U.S.’ overall Indo-Pacific strategy.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News