What’s new? South Sudan’s rulers keep a tight grip on its oil wealth, blocking outside scrutiny and obstructing reforms urgently needed to ease both popular hardships and political tensions. Along with International Monetary Fund support, a peace deal has kickstarted new efforts to fix the country’s broken finances.

Why does it matter? South Sudan’s five-year civil war killed up to 400,000 people and brought the young nation close to collapse. If President Salva Kiir’s government begins to clean up the country’s budget, as it has pledged to do, opponents will have fewer incentives to take up arms again.

What should be done? Reform-minded South Sudanese and their external partners should focus on making the oil economy more transparent and accountable by ensuring that revenue deposits go in a single public account and through other anti-corruption measures. Donors should press commercial lenders to disclose their payments to Juba and follow South Sudanese law.

Executive Summary

South Sudan’s rotten state finances are derailing the young country from its already fraught path to peace and stability after a brutal civil war. Top officials hold the country’s oil riches close, barring scrutiny of spending and allowing rampant misappropriation of funds. This slush-fund governance is at the heart of South Sudan’s system of winner-take-all politics and helps explain why so much went so wrong so quickly after independence in 2011. The peace deal signed in 2018 could help, as it includes reforms designed to combat corruption and build more accountable public finances. But, for the most part, the new government has slow-rolled or evaded implementation. Reform-minded South Sudanese and outside partners should narrow their focus to those measures that begin to pry open the lid on the country’s oil wealth, ensuring, for starters, that oil revenues are deposited in a single public account. Simultaneously, donors should consider commercial levers to make South Sudan’s finances more transparent and accountable to its people, a critical step in halting the country’s tailspin.

The South Sudanese people have suffered terribly from the failure of their leaders to forge a peaceful foundation for the new country. Just two years after independence, the country fell into a civil war that raged for years and left up to 400,000 dead, a shocking toll in a country of only some 12 million. Peace talks led by neighbouring leaders resulted in the 2018 agreement and a power-sharing arrangement between President Salva Kiir and his main rival, Riek Machar, though an insurgency continues in the south. But the government is riven by internal power struggles and its reluctance to lift the shroud from upon the oil economy is blocking reforms that could sustain a broader political settlement.

Oil has always been central to South Sudan’s political fortunes. The landmark 2005 peace deal that paved the way for its secession from Sudan granted Juba 50 per cent of the South’s oil revenues, pumping billions into the new semi-autonomous government as it prepared to stand on its own. The easy money quickly built a vast patronage system that helped unite rival camps but also papered over the country’s deep ethno-political divisions. This largesse abruptly ended as President Kiir moved to consolidate power after independence, sidelining his rivals and firming up his grip on the oil economy. The result was to fracture the country into warring ethno-political camps that continue to be a source of instability despite the formation of a unity government in 2020.

As South Sudan struggles to recover from civil war, its broken state finances are receiving renewed attention. During the war, Kiir mortgaged future oil exports for advance loans from a small group of commodity traders and commercial banks, piling up debt while hiding the country’s finances ever further from sight. Meanwhile, his loyalists diverted large portions of state revenue from the official budget, which is so leeched that the government routinely fails to pay salaries. The result is a cash-strapped state and a deeply aggrieved population with little confidence in its leaders, amplifying political and ethnic animosities.

Stabilising the country appears impossible without fixing its economy. South Sudan is a divided and fragile state that requires fairer power sharing in the centre and a devolution of authority outside Juba, but the parties cannot reach such a political settlement until they are adequately accounting for and sharing the oil funds. Frustrations are also boiling over among donors, who increasingly believe that their huge sums of humanitarian aid are sustaining a kleptocratic elite.

An acute economic crisis triggered by falling oil prices in 2020 opened a window to press for changes, but an uncoordinated approach could squander the chance. Over a ten-month period starting November 2020, South Sudan received some $550 million in relief from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a lump sum equivalent to past annual budgets. The IMF received promises of some reforms but there were few strings attached. This support helped Juba stave off further slides in its currency but left many reform-oriented South Sudanese and donors frustrated that a government in such disrepute and so resistant to reforms received so much for so little.

A more coordinated strategy is needed. Drawing from the 2018 peace deal’s ambitious reform agenda, and the government’s technical commitments to the IMF, South Sudanese reformers and outside actors should pursue more select financial reform priorities that can redirect oil revenues back onto the books of the national budget. These should include the public disclosure of government revenues and debts, aided by the designation of a single oil revenue account, as well as efforts to shore up the weak guardrails that to date have permitted the looting of government deposits. Future IMF disbursements and donor support should require such transparency in total oil revenues, rather than simply accepting better management of funds that make their way into the official budget.

One further way for donors to boost their limited influence in Juba is through systematic engagement with the commodity firms, and their bankers and insurers, upon which South Sudan depends. For instance, donor governments should use the threat of regulation to encourage companies to disclose their payments to Juba, consistent with the way these companies increasingly disclose payments in other places. If they fail to do so, governments can consider demanding special licences that require such disclosure and certify compliance with South Sudanese law for companies under their jurisdiction to operate in South Sudan’s oil sector. Banks and insurers should protect themselves from legal and reputational exposure by requiring the same of their customers who do business in South Sudan.

At the same time, South Sudanese authorities and outside powers must start thinking now about South Sudan’s impending transition from a carbon economy as its oil production declines, new investment in it looks less attractive and the world sets bolder decarbonisation targets. In particular, donors should consider how their present and future support might help reconfigure, rather than reinforce, the top-down, centralised political economy that has led to such bloody destruction. Reform will not come easy, given the incentives for President Kiir and his allies to cling to South Sudan’s oil wealth. If the political class and outside powers do not succeed in convincing Kiir to enact these reforms, however, the country could squander an opportunity to find its footing before its wells run dry.

Juba/Nairobi/Brussels, 6 October 2021

I. Introduction

South Sudan’s slide into civil conflict, barely two years after it achieved independence in 2011, has left the young nation and its outside backers with the herculean task of halting its tailspin while forging a political path forward. A violent contest for power, partly driven by the political elites’ desire to control the country’s oil revenues, has exacerbated its deep ethno-political and regional divisions. The linchpin of South Sudan’s economy, oil accounts for 85 per cent of government revenue and over 94 per cent of exports.

Prior to its independence from Sudan, the South’s case that it could build a viable state was straightforward. Even though the region did not have strong institutions, a cohesive army or an internal political settlement, the South Sudanese pinned their hopes on their oil wealth, arguing they could use it to build the state, create jobs and develop infrastructure. The petrodollars were indeed substantial: despite sky-high poverty and underdevelopment rates, at its birth South Sudan qualified as a middle-income country based on its per capita GDP.

Instead of propelling the young country forward, however, oil helped hold it back. Under President Salva Kiir, oil revenues supplied a slush fund for patronage politics and personal enrichment that the elite squabbled over. In 2013, a leadership struggle that included a fight over this giant prize degenerated into civil war. Peace efforts, in turn, have repeatedly turned into an exercise of squeezing subventions for as many belligerents as possible into the state budget. Although Kiir (from the Dinka ethnic group, the nation’s largest) and his main opponent, Riek Machar (an ethnic Nuer, the nation’s second largest such group), signed a peace deal in 2018 and formed a unity government in early 2020, their accord could easily crumble as combatants turn their guns on each other again.

Meanwhile, attempts by some officials to bring transparency to public finances and curb corruption continue to flounder: the books recording the oil revenues remain closed. After the global plunge in oil prices pushed the state into fiscal crisis in 2020, the government is more willing than before to discuss reforms of its murky finances in hopes of attracting badly needed support and investment. But South Sudanese activists and external partners will need a concerted strategy to take advantage of that window, lest South Sudan’s money continue to disappear with scarcely a trace.

This report examines South Sudan’s oil economy and its role in the country’s upheaval. It outlines recommendations to the South Sudanese and their external partners to make the country’s finances more transparent and their custodians more accountable, with an overall objective of reducing incentives for bloody struggles over power. The report is based on dozens of interviews with South Sudanese officials and activists, foreign diplomats and private-sector actors conducted in South Sudan, the U.S., the UK, Belgium, Netherlands, France and Switzerland in 2020 and 2021, as well as an extensive review of the available documentation of the country’s finances.

II. Polluted Politics

A. Oil, Independence and Civil War

War has beset what is now South Sudan for over half a century. Insurgents took up arms against Khartoum’s rule on the eve of Sudan’s independence in 1956, ushering in protracted civil strife that left as many as two million people dead. But while the dominant narrative had the “African” south pitted against the “Arabised” north, Southerners were fighting for decades among themselves as well, primarily along ethnic and communal lines.

The discovery of oil in the late 1970s intensified the conflict with Khartoum. In the late 1990s, under President Omar al-Bashir, Sudan escalated its counter-insurgency in the South to clear the way for development of oil fields, most of which are located just south of today’s Sudan-South Sudan border. It won some battles but drew condemnation for its abuses of civilians, which also broadened Western and especially U.S. sympathy for the Southern cause. Regional peace talks and strong-arming by the George W. Bush administration finally helped convince Bashir, who feared U.S. military intervention, to accept a 2005 peace deal with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), the political wing of the insurgent Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), that promised the South a secession vote six years later. Khartoum also consented to give the newly semi-autonomous South 50 per cent of revenues from the oil produced there, a bonanza for an area roughly the size of France with only a smattering of small market towns.

” Oil … laid the groundwork for South Sudan’s secession. “

Oil thus laid the groundwork for South Sudan’s secession. Flush with petrodollars, the SPLM’s rebels-turned-rulers could have not wished for more propitious timing: international oil prices reached new highs in 2004 and kept climbing, briefly soaring above $100 a barrel for the first time in 2008, then hovering above that mark from 2011 until 2014.

Led by Kiir, the SPLM quickly forged Southern consensus behind independence by handing out plum positions and promising a broad-based government after secession, which was all but a fait accompli by the time the 2011 referendum arrived.

But the sudden wealth gravely compromised the country’s stability. The SPLM had always been a shoestring operation, with field commanders largely left to finance their own units through a mix of taxation, aid diversion, cattle rustling, artisanal mining, logging and outright looting. During the war with Khartoum, some top rebels enriched themselves, buying upscale homes in Nairobi and Kampala. The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement and the accompanying oil money propelled the elite’s propensity for illicit self-dealing to new heights. The influx of billions of dollars into a proto-state without established institutions resembled a free-for-all.

Some officials, meanwhile, justified their scramble for oil money as recompense for decades of wartime suffering.

Pervasive corruption quickly helped erode Southern solidarity. Ethnic mistrust hardened as oil revenues appeared to concentrate in the hands of the SPLM elite, which many Southerners viewed as dominated by Kiir’s ethnic group, the Dinka. Since many smaller Southern ethnic groups had spent decades resisting the SPLM’s dominance, they remained on the periphery of the new quasi-official patronage network. Resentment deepened after a string of corruption scandals, including the 2008 “Dura saga”, when the government of the then semi-autonomous region awarded some $3 billion of contracts (at the official exchange rate) to a range of companies for the purchase and storage of cereals that mostly never arrived.

In 2012, Kiir said the government could not account for $4 billion, dispatching dozens of private letters accusing senior officials of embezzling funds in the lead-up to independence, a move that further ratcheted up internal tensions.

After independence, oil emerged again as a cause of trouble. Facing deadlocked negotiations over how much to pay Sudan for the use of a pipeline transporting crude from Southern oil fields to export via Port Sudan on the Red Sea, Juba shut down its oil production in 2012 to force Khartoum’s hand. South Sudan’s army then captured the Heglig oil fields just across the border inside Sudan, triggering a short-lived border war before pulling back amid global outcry. Having cut off its only source of revenue, the government secured over $1 billion in oil-backed loans to tide itself over until exports resumed, a mechanism it would later deploy to fund itself during South Sudan’s civil war, in effect mortgaging the state’s future.

Government unity crumbled soon thereafter. Senior party officials began manoeuvring to challenge Kiir’s SPLM leadership and, therefore, his presidency. Kiir meanwhile abandoned his strategy of political inclusion and moved instead to consolidate power, tightening his own grip on the oil funds in the process. Discontent grew within the SPLM. The dispute escalated in 2013, when Kiir sacked Machar, who served as his vice president, along with many other top party officials. In December that year, gunshots rang out after a party conference as Dinka and Nuer elements of the elite presidential guard tasked with protecting both Kiir and Machar exchanged fire, plunging the nation into weeks of ethno-political bloodshed that descended into a five-year civil war. The conflict disrupted oil production, then drained South Sudan’s coffers. Fighting erupted just as a global commodity boom slowed, sending oil prices below $80 per barrel. Since South Sudan had based its export fee negotiations with Sudan on boom-time prices, the oil slump further eroded government income.

” Widespread discontent with the government’s failure to improve South Sudanese people’s dire living conditions is putting the peace deal at further risk. “

The ruling elite’s predation continues to threaten South Sudan’s stability. Though the 2018 big-tent peace deal brought the two main belligerents Kiir and Machar somewhat closer, on paper at least, and eventually led to a unity government, the simmering insurgency in Central Equatoria remains unresolved, in part because a rebel leader refused to sign out of frustration with, among other things, Juba’s monopoly on the country’s oil wealth.

More critically, as noted, Kiir has yet to fulfil many of the pledges he made in the peace accord, such as incorporating former rival fighters into the army, often on the grounds that his government lacks the funds. Opponents view these claims as spurious and proof that Kiir has no intention of sharing the country’s wealth with non-loyalists, while Machar also faces accusations that he is hogging the spoils of peace.

Widespread discontent with the government’s failure to improve the South Sudanese people’s dire living conditions is putting the peace deal at further risk of collapse and feeding perceptions that armed struggle is the only avenue for effecting political change.

B. Obstructing a Settlement

As even South Sudan’s leaders acknowledge, the fight for petrodollars underlies much of its internal political strife, while fanning the flames of its ethnic and regional divisions.

To be sure, these problems owe much to decades of colonial and Sudanese neglect that left South Sudan one of the least developed places in the world. Yet oil-dependent countries often suffer from political pathologies, and South Sudan is no exception. The pot of oil revenues claimed by those atop South Sudan’s system dramatically raises the stakes of holding power, accentuating the winner-take-all nature of South Sudanese politics (which as discussed prevails even now, notwithstanding the power-sharing arrangement between Kiir and Machar). This centralised contest for oil money thus also obstructs the political reforms South Sudan so desperately needs, including, as Crisis Group has previously recommended, the adoption of a more consensual form of national governance and a devolution of authority and resources.

” [President] Kirr’s hold on oil revenues clearly works against more equitable power sharing. “

Kiir’s hold on oil revenues clearly works against more equitable power sharing. His loyalists dominate the finance ministry, the Central Bank and the state-owned Nile Petroleum Corporation, known as Nilepet. Furthermore, despite the 2018 peace deal’s power-sharing provisions, Kiir’s confidants, including close kin and loyal lieutenants, operate as a shadow government, bypassing the institutions the formal administration controls in cooperation with the political opposition, and thus retaining the real balance of power and fuelling discontent in Machar’s camp.

The presidency’s centralised control of oil funds – and desire to maintain it – also complicates efforts to meet widespread demands for greater decentralisation, as the SPLM originally promised, or even to open up space for dialogue among South Sudanese about what proportion of national funds should flow to state and local administrations. Of the 5 per cent of oil revenues that the constitution obliges the government to send to oil-producing states and counties, little appears to reach those destinations.

Further, South Sudan’s petroleum politics empower the elite most resistant to change. Kiir’s government has spent the bulk of oil funds that did reach the budget on the military and the security sector, instead of building basic services that could alleviate the population’s suffering. During the war, his administration predictably bolstered the army and the infamous National Security Services, while also backing government-aligned militias.

These institutions acquire additional off-budget funds through Nilepet, and through the operation of private security companies guarding the oil fields.

These additional off-budget revenues not only insulate much of the officer corps from oversight but also provide them with powerful financial incentives to protect the status quo. The top brass itself sponsors militias across the country, undermining efforts to tame violence persisting after the 2018 peace agreement.

C. A Hazy Future

Given the scale of the problems, it seems entirely possible South Sudan might be better off without oil – and such a future could be nigh. The country’s production peaked at over 300,000 barrels per day at independence but has decreased to half that, in part due to the conflict, and South Sudan’s government projects oil production to continue to halve roughly every five years.

Volatile oil prices, instability and the poor quality of much of South Sudan’s crude, meanwhile, discourage investment needed to repair damaged wells, extend their lifespan and search for new deposits. The high costs and fraught politics of exporting South Sudan’s oil through Sudan further deter prospective investors, which already face the prospect of global decarbonisation.

” Any move away from [oil] production would precipitate a collapse in the government’s income and diminish [its] legitimacy. “

Since oil underwrites the entire South Sudanese state, any move away from production clearly would precipitate a collapse in the government’s income and further diminish the authorities’ threadbare legitimacy. Yet the transition may also give South Sudan its best chance at recasting its rentier state. The challenge can hardly be overstated: the government has barely paid attention to the agrarian and pastoral economies, which sustain much of the population. It has also consistently failed to explore other potential sources of income and has yet to build the roads and infrastructure that could spur economic growth.

It is therefore difficult to imagine what a post-carbon future would look like absent significant external support, and South Sudan thus faces a critically short window to improve its relations with the outside world. Still, given how much of South Sudan’s politics revolves around this centralised resource, a transition away from oil also presents the clearest opportunity to change the entrenched power dynamics in South Sudan that have proven so destructive.

III. Emptied Coffers: Siphoned Off and Pre-sold

A. The Path of a South Sudanese Petrodollar

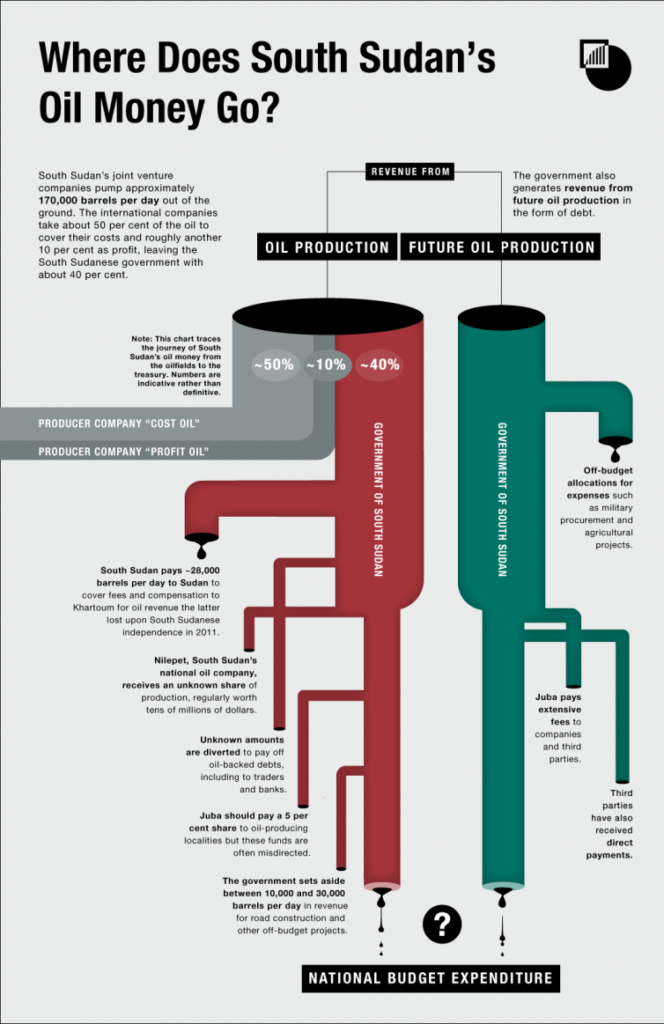

South Sudan earns income from less than half of the roughly 150,000 to 170,000 barrels a day it produces. The proceeds of around 55 to 60 per cent of total output goes to the three joint venture oil producers in the country, as profit and to cover their costs.

According to the UN Panel of Experts, these costs likely include the producers’ contracts with security and other companies working in the oil fields, which are largely controlled by South Sudan’s security elite – one way in which they can likely tap into off-budget funds. South Sudan remains entirely dependent on Sudan to get its oil to international markets, which means that a further 28,000 barrels per day go toward paying Khartoum for the use of its pipelines and paying off a $3 billion compensation settlement South Sudan agreed to after independence.

(The government has said it expects to settle its compensation obligations by the end of 2021, though transit-related fees to Sudan will remain.)

That leaves South Sudan with the proceeds from up to roughly 35,000 to 45,000 barrels per day at present production levels, according to the best estimates available. Much of this money is vulnerable to diversion before it reaches the national budget, however. Nilepet regularly receives tens of millions of dollars in oil revenues from producing companies and the government, but these allocations are not reliably disclosed and have never been audited.

Tightly controlled by Kiir loyalists and the security elite, the state-owned company appears to fund parts of South Sudan’s security services and war machine.

Other ad hoc forms of budgeting obscure the country’s finances. In 2019, Kiir announced he was setting aside 30,000 barrels of oil per day for road projects with Chinese companies, overseen directly by the Office of the President, though the government can now only afford to fund the project with 10,000 barrels per day.

This opaque arrangement shields substantial revenues from oversight and has already led to scandal, including accusations of mismanagement and corruption. Kiir has since promised to “dedicate” 5,000 barrels per day to pay government salaries, a move that would make little sense if South Sudan had a functioning budget.

More oil funds still are used to repay hefty commercial loans, including from the Qatar National Bank, the Africa Export Import Bank and the commodity traders, including Sahara Energy.

A 2013 law stipulates that all oil revenue is to be deposited in a single Petroleum Revenue Account. The government’s failure to do so resulted in a clause in the 2018 peace deal ordering the closure of all other petroleum accounts.

Three years on, the authorities have yet to implement that provision. In addition to these ad hoc allocations, both the government and Nilepet receive payments from sales, fees and resource-backed loans in several international accounts.

In the past, the government instructed some buyers of its oil to make payments directly to third parties. This fragmented, ad hoc system creates an ideal climate for large-scale misappropriations of cash.

The management of funds that do reach the budget is equally poor. Weak institutional guardrails and limited oversight facilitate fraud and embezzlement, including “ghost worker” payrolls and collusive contract schemes, which can alone account for billions of dollars in missing funds.

The government did not even publish a budget for the 2020-2021 financial year, while expenditure reports are typically late and incomplete. Even a recent government audit of the use of the first batch of International Monetary Fund (IMF) funds found that millions could not be accounted for. In sum, South Sudan’s official budgeting often has little to do with how the state funds itself or where the money goes.

B. Wartime Lenders of Last Resort

Oil-backed loans further cloud South Sudan’s financial horizons. Racked by civil war and hamstrung by limited access to international capital markets, South Sudan started using its future oil shipments as collateral in exchange for quick cash soon after independence. Since 2012, South Sudan appears to have received some $2 billion, at least, in advanced oil sales.

While these oil-backed loans brought in new revenue, the government never disclosed the loans’ contract terms or repayment schedules, obscuring the long-term implications. Its repayment obligations then deprived the treasury of revenue and foreign exchange, as lower oil prices meant more oil was needed to pay off the same amount of debt, pauperising the country’s balance sheets. According to the ministry of finance, more than 86 per cent of the country’s $1.51 billion in external debt as of 2020 was owed to commercial lenders.

As mentioned above, the South Sudanese elite’s debt acquisition habits started developing before the civil war, when Juba borrowed over $1 billion against future oil production from the China National Petroleum Corporation and Malaysia’s Petronas, two of the main oil firms operating in the country, during the 2012 oil shutdown. In 2012, the government also started a commercial relationship with the Qatar National Bank which eventually grew into a $650 million loan that Juba is still servicing with the delivery of two cargoes of crude oil per year.

South Sudan then started to turn to less orthodox lenders: commodity traders.

A handful of trading firms purchased most of South Sudan’s oil from 2013 onward and then started lending the government money through “pre-payment arrangements”, the sum totals of which neared, if not exceeded, $1 billion. These payments work like the petrostate equivalent of a payday loan scheme: the government gets cash advances at high interest rates in return for future oil deliveries. As lenders typically pre-pay in dollars but get repaid through crude oil, oil price fluctuations can require the government to ship far larger quantities than anticipated at the time of the agreement. Discounts on the value of future oil and fees can make these deals even more expensive for Juba.

South Sudan has little to show for these secretive pre-payments.

Only a handful of officials know the terms of the pre-sales, and their power to line pockets today with tomorrow’s riches has mostly served to heighten their political opponents’ fury and ordinary citizens’ sense of injustice.

Furthermore, the availability of this financial lifeline may have emboldened the government to resist enacting reforms that attract more traditional forms of budget support, while the resulting debt pile shrinks future leaders’ capacity to arrest South Sudan’s tailspin.

” South Sudanese leaders have repeatedly pledged to halt advanced oil sales … but found the habit hard to kick. “

South Sudanese leaders have repeatedly pledged to halt advanced oil sales, including in the peace deal, but found the habit hard to kick. In June 2019, the government announced it had suspended pre-payment arrangements and set up a committee to investigate the practice, but the IMF found that such loans had continued until at least the following May. As of April 2021, South Sudan still owed Sahara Energy $99 million, but had reportedly cancelled its loan facility with the company and said it planned to clear the debt by September. In 2019, the Africa Export-Import Bank gave the government an additional $400 million credit line, to be repaid through the allocation of future oil cargoes.

Regardless of whether they are still purchasing the oil in advance, commodity traders remain the key buyers of the South Sudan government’s share of oil, according to the ministry of petroleum, a significant shift from the early days when Chinese firms purchased the vast bulk of South Sudan’s allotted cargoes.

In 2020, the petroleum ministry identified nine companies as having purchased the government’s entire annual share of oil exports: all were either standalone commodity traders or trading arms of major oil companies, the majority of which have a strong corporate presence in Europe. As a result, a small circle of traders, plus the banks and insurers that underwrite them, many of which are headquartered in the world’s financial capitals, have outsized influence upon South Sudan’s finances and politics.

C. IMF Relief

South Sudan plunged into a fiscal crisis in 2020. Floods, locusts and the COVID-19 pandemic had already precipitated an economic downturn when a steep drop in oil prices halved the government’s revenue while doubling the amount of oil it needed to repay its creditors.

In August of that year, the Central Bank announced that it had run out of foreign reserves and would be unable to stop the South Sudanese pound from depreciating. As national and state authorities laboured to keep down consumer prices on staples like water (which must be purchased because treated water is not publicly available) and food, the government decided to print money, which in turn further fuelled inflation. Internal documents said government revenue would decline 60 per cent from previous projections. Civil servants and soldiers went without pay for months.

The IMF stepped in to provide economic relief, which eventually totalled more than half a billion dollars. In November 2020, the Fund provided its first-ever budget support to South Sudan by releasing $52.3 million in emergency assistance, citing the severe impact of the pandemic and falling oil prices on the country’s public finances.

It followed up quickly with a much larger disbursement of $174.2 million in March 2021, which came with a program that allows the Fund to monitor the government’s commitment to carrying out reform. The IMF identified eleven key measures it expects the government to enact, including monetary and exchange rate adjustments, new anti-corruption provisions, a single treasury account, and improved cash management and cash forecasting. South Sudan then received a further $334 million from the IMF as part of a $650 billion disbursal, the largest of its kind in the institution’s history, to all 190 members.

The combination of IMF stopgap relief and rebounding oil prices has thus far given respite to the government and prevented fiscal collapse, but South Sudan’s economic woes – declining oil production, meagre to no foreign reserves, high-risk debts – are hardly solved. Despite its massive dimensions, the bailout has failed to extract major concessions from the ruling elite, and the program’s critics say future budget support should be tied more directly to verifiable changes.

Furthermore, the IMF loan appears to have aggravated political bickering, despite bringing about few substantive changes other than the rare semblance of transparency in how the funds are used. In particular, the government’s decision to use the money to pay only its own soldiers, and not former opposition forces loyal to Machar, added to the overwhelming disillusionment with the peace process in Machar’s camp, which has since split into two largely as a result of this discontent.

” A protracted fiscal crisis may finally motivate South Sudan’s leaders to mend their broken relations with donors. “

Yet South Sudan’s economic distress may actually have a silver lining. The government is less likely to launch expensive military operations or flagrantly skirt a UN arms embargo to buy new weapons. Insurgents may also have fewer incentives to rebel, since the government has a smaller pot of money with which to purchase peace. More critically, a protracted fiscal crisis may finally motivate South Sudan’s leaders to mend their broken relations with donors.

IV. Mounting Frustrations and the Search for a Strategy

A. Donor Dilemmas

Thus far, donors have struggled to articulate a coordinated strategy pushing for reforms in South Sudan. The government’s failure to provide basic services to its populace is an especially sore spot for major donors, which foot the bills for aid agencies and organisations to provide education, health care, sanitation and more.

Worse, diplomats see few options at their disposal. Donors are understandably reluctant to use relief to a population suffering chronic food shortages as leverage for political or economic reform, given what they view as the government’s cruel indifference to its own people’s hardship. They also fear that punitive measures could make the state even wobblier, in turn worsening the plight of South Sudan’s beleaguered citizens.

Targeted sanctions, Western powers’ pressure tool of choice in recent years, have probably yielded some results but failed to generate substantial reforms. During the Trump administration, the U.S. Treasury Department steadily diverged from the UN and European Union (EU) by adopting a significant number of additional unilateral financial sanctions against South Sudanese companies and individuals, though both the EU and UK have recently added an individual each to their sanctions lists as well.

Many of these measures cited the misappropriation of public funds. Some Western officials believe that this escalation of targeted sanctions, and the threat of more, affected the thinking of South Sudanese elites at critical junctures in the peace process. In particular, they believe that threats of more sanctions helped convince Kiir and Machar to form the unity government in February 2020. Government representatives repeatedly mentioned the sanctions in diplomatic meetings and hired at least two firms to lobby for their removal in the U.S.

Donors have also struggled to get regional powers – especially Kenya, Uganda and Sudan, which mediated in 2018 peace talks – to increase pressure on South Sudan’s leaders to clean up the government’s finances. Kenya’s business-minded elite rarely cracks down on illicit money flows from abroad (even if its diplomats are aghast at the state of South Sudanese politics); nevertheless, Nairobi made news recently by freezing the account of South Sudan’s cabinet affairs minister and key Kiir ally, Martin Lomuro Elia, for suspected money laundering, before quietly unfreezing his funds.

Uganda’s political and military elites, too, share commercial ties with South Sudanese elites and are happy to welcome their channelling millions of dollars into bank accounts in Uganda with few questions asked.

Sudan, meanwhile, would have the most to gain if South Sudan cleaned up its image enough to attract investment in its oil industry, yet its relations with Juba are primarily handled by its military elite, who are unlikely to push for reforms. Khartoum is also swamped by an array of other pressing negotiations with its southern neighbour, including over border disputes, trade relations and peace talks with Sudanese rebels in Juba.

” Most East African officials say they do not believe additional sanctions would be helpful. “

Most East African officials say they do not believe additional sanctions would be helpful. Regional envoys may also have promised Kiir to push for existing economic sanctions to be lifted if he moved forward with the peace deal. Many analysts believe the deeper misalignment is that regional elites suffer little from the status quo as donors pick up the tab.

Since it is clear that punitive measures alone will not prise South Sudan’s oil riches out of the ruling elite’s hands, some donor officials are hoping that IMF engagement could at least create momentum for reforms. At the IMF’s behest, the government set up an oversight committee tasked with coordinating the rollout of key measures in various ministries and institutions, while communicating progress to the Fund and other donors.

A nine-month Staff Monitored Program, which creates a basis for the Fund to monitor the reform program, was attached to the second round of IMF funds and may add impetus to the committee’s work and facilitate greater international oversight. Already as a result of the IMF support, authorities moved the powerful Technical Loans Committee, which oversees government borrowing, from the president’s office back to the finance ministry, which Kiir’s party also controls but is subject to greater oversight. Officials say South Sudanese officials seem keenly aware that current progress could determine the availability of additional IMF funds.

Yet other donor officials fear that the IMF relief could weaken the pressure for substantial reforms. Given their chronic search for leverage, the large influx of IMF money with few major up-front reforms surprised many, even though some of their own governments sit on the IMF board. This makes clear the IMF engagement was never integrated into a broader coordinated donor strategy in South Sudan.

Some Western capitals may also turn their focus on other priorities, given the IMF lead on the financial reform agenda, potentially leading to less pressure overall. The speed of the disbursals was also a surprise: the IMF dispensed the second, larger round of funds before the government’s internal watchdog completed its audit on the first batch. The audit found millions of dollars could not be accounted for.

B. A Laundry List of Reforms

Following the peace deal and new IMF engagement, domestic reformers and international backers still have a window to press for meaningful financial reform. By agreeing to form a unity government in February 2020, President Kiir hoped in part to improve his relations with the country’s key Western donors. Today, he faces an economy that will struggle to stay afloat once the IMF relief runs out.

South Sudanese activists and outside partners lack a clear roadmap to achieving such reforms, however. The most obvious reference point for South Sudanese and donors to press for improved state finances has been the detailed pledges all parties in the unity government made in the 2018 peace deal, which envisages an overhaul of South Sudan’s oil sector and public finances. Commitments include opening South Sudan’s books and thus bringing transparency and oversight to government revenues, debts and expenditures, largely in line with South Sudan’s existing laws. They also include the reform of major institutions such as the Central Bank; enquiries into key government bodies involved in the oil economy; the creation of a least six new agencies to strengthen management of public finances and resources; and the review of at least twelve major pieces of legislation relating to management of the economy. All in all, the peace deal’s financial reform roadmap binds the government to take at least 65 distinct steps, few of which it appears to be making much headway in taking.

” [The South Sudanese] oil sector is governed by strong legislation that needs to be enforced rather than revisited. “

Sensible as it may be, the laundry list approach lacks strategic focus and is thus unlikely to lead to more than a few piecemeal changes. More critically, the country’s oil sector is already governed by strong legislation that needs to be enforced rather than revisited. Against this backdrop, perhaps the most important step donors could take would be to identify a handful of key reforms along the lines highlighted in Section V that would be at the very top of the long list of priorities that activists and diplomats are already pressing government officials on – a list that currently includes progress toward elections, reduction of insecurity, constitutional reform and justice for victims of war crimes, to name a few. Even the shorter list of IMF priorities may still be too extensive, if the goal is substantive change.

Still further commitments Juba made to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), following South Sudan’s addition to its “grey list”, adds to the muddled reform agenda.

V. Pressing for Change

A. Priority Reforms

Amid the financial wreckage, reform-minded South Sudanese and outside powers need to figure out where to focus. Ideally, Kiir would enact all the reforms his government has committed to. In practice, though, those seeking reforms will need to be more strategic, prioritising for the near term the particular steps most likely to bring change.

South Sudanese and their outside partners should start by coalescing around the demand for a single, designated, transparent oil revenue account, as required by South Sudanese law and as the government agreed to create in both the peace deal and with the IMF. They should also insist that its balance and activity be regularly disclosed publicly in accordance with South Sudanese law.

Although no panacea, such a change is a key first step toward the regular disclosure of South Sudan’s revenues and loans, without which credible public finances are all but impossible.

While the designation and exclusive use of a transparent public oil account should be a precondition for improved ties with donors, other steps will also be necessary. Most urgent is the immediate disclosure of all government revenues and debts, a prerequisite for almost all other critical reforms as well as for rebuilding trust between the government, the population and donors. This disclosure should include timely publication of accurate budget documents, expenditure sheets and oil marketing reports, as well as the allocations of oil to Nilepet and other off-budget projects, a practice which should end.

Until such transparency exists, donors and international financial institutions, including the IMF, should decline to provide further budget support.

But transparency alone will be insufficient. Corruption is endemic, and manifest in tactics ranging from unbudgeted withdrawals, inflated procurement contracts and ghost workers to exchange rate manipulation and self-dealing oil-field service contracts.

The newly established Public Financial Management Oversight Committee and its subcommittees offer an important focal point for emplacing guardrails against these practices, but they need to show they can deliver results by limiting the practice of unbudgeted withdrawals for private use and by ensuring ministries produce regular budget and expenditure reports that reflect actual government spending. Given its rock-bottom reputation among donors, the government may need to accept external oversight and auditing.

There could be easy wins, too. Kiir’s entourage may retain the balance of real power, but an array of new officials, including long-time Kiir opponents, hold positions of authority in the unity government. They have already taken positive steps. In February 2020, for instance, the petroleum ministry, led by a Machar ally, published the first Oil Marketing Report – a vehicle for sharing information on oil sales with the public – since June 2015. It has also committed to releasing monthly production data.

The government should build on these developments and, in accordance with its own laws, ensure regular and timely public reporting of oil production and exports. Donors could support internet portals that regularly update oil production and revenue figures and make key documents, including laws and marketing reports, more easily available to a wide audience.

B. Coordinating Pressure

” South Sudan cannot fix its politics without restoring credibility to its public finances. “

Few expect Kiir to loosen his grip on state finances of his own accord, given that his mode of politics relies on patronage networks and off-budget financing. To increase pressure on his administration, reform-minded South Sudanese – particularly civil society and religious leaders, but also disenchanted politicians – should to the degree they can do so safely build a coalition with regional allies and (where helpful) donors to coordinate their messaging, driving home the point that South Sudan cannot fix its politics without restoring credibility to its public finances, while doing their part to safeguard the work of civil society and journalists.

South Sudan’s neighbours can be of particular assistance. Sudan, which has pledged to make its own oil sector more transparent, could eventually help shed light on South Sudanese oil exports that transit its territory by disclosing more about its own industry. Kenya and Uganda should strengthen and enforce regulations to combat money laundering, particularly in the commercial banking and real estate sectors, which are benefiting from the proceeds of South Sudanese corruption. Both countries have incentives to do so. Uganda has landed on the FATF’s “grey list”, leading the EU to designate it as a “high-risk third country”.

Kenya’s next assessment under the FATF framework is under way, with results expected in 2022.

Donors, meanwhile, should better articulate both what they expect South Sudan’s government to do and what it might get in return – and stick to these priorities and commitments. In doing so, the IMF and donors must resist the temptation to latch on to any single reform as proof of South Sudan’s commitment to change. For example, President Kiir may well offer greater transparency over non-oil revenue streams in exchange for more budget support; donor institutions should reject this trade-off, demanding transparency in oil revenues, where the rot in South Sudan’s finances originates. The IMF in particular should not take transparent management of its loans to South Sudan alone as evidence of meaningful progress and should integrate the findings of South Sudan’s own audits of these funds into its Staff Monitored Program.

Greater coordination among the IMF and donors, and within donor governments, is also required. Many donor officials expressed frustration or surprise at the sudden disbursement of IMF support to South Sudan in late 2020 and early 2021, without any coordination over how this might be leveraged to encourage reform.

IMF officials, for their part, maintain that the Fund has a technical mandate and that it relies on its board to provide political oversight of its activities.

Donor governments should accordingly increase their engagement with the IMF at senior levels, including with board members, to make sure that the Fund’s efforts in South Sudan are not at cross-purposes with attempts to improve governance in Juba. Meanwhile, IMF officials should also recognise the deeply political nature of any assistance and strive to align their efforts more closely with other diplomacy.

Lastly, donors should not ignore their most important allies: the South Sudanese people. Kiir and Machar are deeply unpopular both within their own camps and among the wider population. Diplomats should make clear to both the political class and the citizenry the costs and missed opportunities of their leaders’ failures. Donors should emphasise that they are prepared to reset relations with South Sudan, whether it is through a pledging conference or additional World Bank support, if and when South Sudan’s ruling elite embarks on a more credible political transition, which would likely require both Kiir and Machar to step aside. They should also speak up in defence of journalists and civil society activists who focus on corruption or financial reforms and are routinely arrested or harassed because of their work, including by the National Security Service, which is among the beneficiaries of IMF funds.

C. Corralling Commercial Actors

The small number of international firms that provide a large percentage of South Sudan’s revenues require more attention, too. The U.S. currently regulates the export of certain goods to designated South Sudanese companies through special licenses (discussed in Section V.D).

Using these and other mechanisms there is more they could do.

For starters, donors and external partners should state clearly to commercial actors under their jurisdiction that they expect them to follow South Sudanese law, including by routing all payments to a single designated oil account and making sure their contracts expressly require compliance by all parties with the country’s laws.

South Sudan has sold a majority of its oil cargoes to companies with an established presence in Europe since the outbreak of civil war, while the rest went to firms with ties to China, Russia and the United Arab Emirates. While Western governments may be the most likely to do so, all of these governments should encourage these companies to disclose all payments and loans to South Sudan, something that the companies might be willing to do if urged to do it collectively and some already do in other countries where they operate.

Banks and insurers, too, should require that all contracts by clients operating in South Sudan comply with South Sudanese law, which would help protect their reputation and guard against legal risks. Transparency among foreign commercial partners could also motivate Juba to open its own books, since these disclosures would mean that South Sudan itself has less to hide.

Objections that such disclosure requirements, if imposed solely or primarily by Western governments, would only lead Juba to favour non-Western firms or force Western firms out of the South Sudanese market are misplaced. South Sudan is not in a position to turn away business, while shrinking profits have nudged most traders to look for new markets, rather than abandon them. Oil companies, moreover, have regularly disclosed payments elsewhere when legally required to do so in the U.S. and EU, while commodity traders have slowly started to report under voluntary standards established by the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

Further, even if some Western firms did leave the South Sudanese market, nothing suggests that their present trading or disclosure behaviour is currently any better for South Sudan than that of the non-Western firms that could replace them.

” Companies should be aware that their involvement in South Sudan has clear reputational and regulatory risks. “

Corralling these commercial actors will require governments to open formal or informal channels with their management. At present, the companies complain that messages concerning commerce in South Sudan, including industry-wide alerts, are vague and inconsistent across Western jurisdictions, meaning they invest in little beyond minimal legal compliance. Donors can provide more regular advice on corruption risks in South Sudan, as the U.S. and UK have begun to do, while taking care not to discourage responsible investment in South Sudan and acknowledging that companies are wary of being treated as foreign policy tools.

Yet companies should be aware that their involvement in South Sudan has clear reputational and regulatory risks should they not follow South Sudanese law and engage transparently.

D. Carrot-and-Stick Approach

If South Sudan’s leaders fail to take the opportunity to carry out meaningful reforms, as their track records suggest they will, donors face a range of unappealing options.

As noted above, additional targeted sanctions are an option, though by themselves they are hardly likely to be transformative. Applying or threatening targeted sanctions can shift individual behaviour at key junctures but is unlikely to bring systemic change. The costs can also be high and indiscriminate; even targeted sanctions can throttle legitimate businesses and cut off civilians from banking services in an economy that offers only limited commercial appeal to banks. Still, countries such as Kenya, Uganda, the U.S. and the UK could do more to pressure the ruling elite, notably by threatening to seize assets or end family education privileges abroad, especially if they tied the threat or application of these measures to specific demands and commensurate positive incentives. If countries applied such pressure in conjunction with conditioned offers of IMF or other donor support tied to requests for reform, then donors could employ a strategic carrot-and-stick approach that has thus far been lacking.

Furthermore, the U.S., UK, Switzerland and the EU could consider requiring special licenses for people and businesses under their jurisdiction to operate in South Sudan that are conditional on transparency measures and compliance with South Sudanese law. Trade with South Sudan’s oil sector would thus require a permit from relevant government authorities. The EU insists on a similar licence for exports to Russia and Iran, while the U.S. already requires licencing for the export of certain goods to fifteen companies in South Sudan.

A licencing regime could make the purchase and advance purchase of South Sudanese oil, as well as the financing and insurance of such transactions, subject to a permit requiring public disclosure of all related payments to the government as well as demonstrable adherence to other South Sudanese laws. The threat of such regulation could also be used as an incentive for commercial actors to work with donor governments on voluntary collective disclosure of their activities in South Sudan.

Some South Sudanese believe that outside assistance is also entrenching a predatory elite.

Donors’ long-term presence in South Sudan risks becoming a clear moral hazard, should it allow the government to forever neglect its population. But the nuclear option of threatening to limit or cut off aid if South Sudan’s leaders continue to pilfer oil funds is polarising, and rightly so, given the potential humanitarian fallout. In any case, few donors are willing to seriously consider any strategy that risks hurting the South Sudanese people in the near term. Rather than speculating about this possibility, donors should do more due diligence to make sure less assistance falls into the hands of Juba elite through logistics subcontracting, rent and exchange rate manipulation, and by expanding their footprint as much as possible outside Juba. Toward that end, donors could also consider shifting more assistance to direct cash transfers in rural areas, as is being tried in Somalia and Sudan.

The only durable route to fixing South Sudan’s finances, and the aid conundrum, is through its politics. Financial remedies alone will not fundamentally change South Sudan’s system of predatory winner-take-all politics, which reinforces the widely held sense that the use of force is the only way to obtain a share of power. As Crisis Group has previously argued, the South Sudanese should agree to some form of decentralisation to reduce the government’s power, devolving power and resources locally. Donors who have grown frustrated with the country’s political quagmire should push regional leaders and the AU harder to convince the ruling elite of the need for a more consensual form of governance. Many South Sudanese, fearing more power struggles, desperately want a political reset: the National Dialogue, which concluded in 2020, called on both Kiir and Machar to step aside instead of competing in forthcoming elections, possibly scheduled for 2023.

E. Beyond the Petrostate

The South Sudanese and their long-term donors also need to start thinking about South Sudan’s inevitable transition from a carbon economy. When the oil wells dry up or stop producing, as they eventually will, South Sudan will become much more reliant on state-level administration and revenue collection, as well as local economic growth. As mentioned above, the coming end of oil is yet another reason why authorities should speed up the devolution of power, a widespread demand of the South Sudanese population, which would make local administrations less dependent on a revenue-starved future central government.

For their part, one fairly novel option that donors could consider would be to offer conditional budgetary support in exchange for leaving oil in the ground, with an eye toward piloting a future global initiative to low-income countries that will struggle to move to a decarbonised economy.

Some observers are already arguing that oil-dependent countries, especially those prone to conflict, may need to be coaxed away from fossil fuels with financial assistance.

Of course, paying Juba not to produce oil might be too much for some donors to swallow, particularly given that they could conceivably renege on their pledge after a year or two and pocket both the assistance money and the oil revenues (although any such assistance could be turned into hefty debt obligations if the government reneges on commitments to keep crude reserves in the ground).

Nevertheless, testing this idea in South Sudan could make sense for several reasons. South Sudan’s oil revenues are small for an oil-dependent economy, and donors are already deeply invested in the country’s welfare. More critically, in few places does the opacity of oil money’s flow so clearly hinder a move away from conflict. To help change the country’s toxic oil political economy, donors could firmly demand that the funds be transparently spent and accounted for by the government in line with the country’s laws and constitution. Further, these conditions can include Juba exploring more non-oil sources of income and growth, such as agriculture or renewable energy. These assistance funds could also be devolved to state-level governments in line with South Sudan’s constitution, thus helping counterbalance the winner-take-all aspect of the country’s politics, which has centralised oil revenue in Juba.

VI. Conclusion

South Sudan’s finances are in ruins. The oil that the South Sudanese once believed would fund the development of their new state instead unleashed, then fuelled, a bloody power struggle. The country’s leaders have emptied the state’s coffers, siphoning off its oil income and mortgaging its future oil revenue. The capture of state resources has helped keep President Kiir and his allies in power, but it has come at great cost to the population and prevents a broader political settlement that could stabilise the country going forward. The South Sudanese and external partners should focus on key reforms that will bring transparency and accountability to its mismanaged public finances. South Sudan’s elite is already staring at the horizon of a post-carbon future, an existential threat to their rickety state. Delaying reforms any longer will only further isolate the country as it nears a time when it will need all the help it can get.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News