The distinctive symbol of the clenched fist has become synonymous with various revolutionary, social and political movements across the world. The imagery of a fist clutching an assault rifle is commonly associated with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and supported armed movements in other countries, such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Yemen’s Ansar Allah (Houthis) and the Fatemiyoun and Zainebiyoun, composed of Shia Afghan and Pakistani fighters, respectively. Yet, there appears to be a new addition in Shia-majority Azerbaijan.

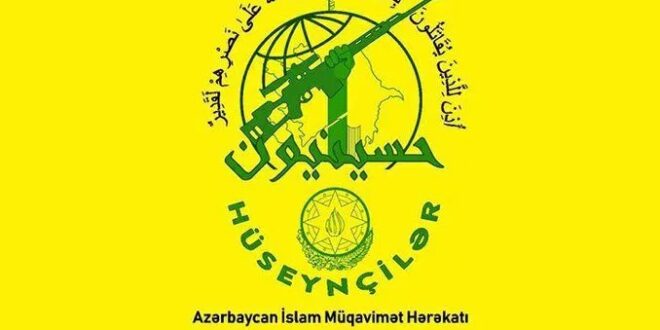

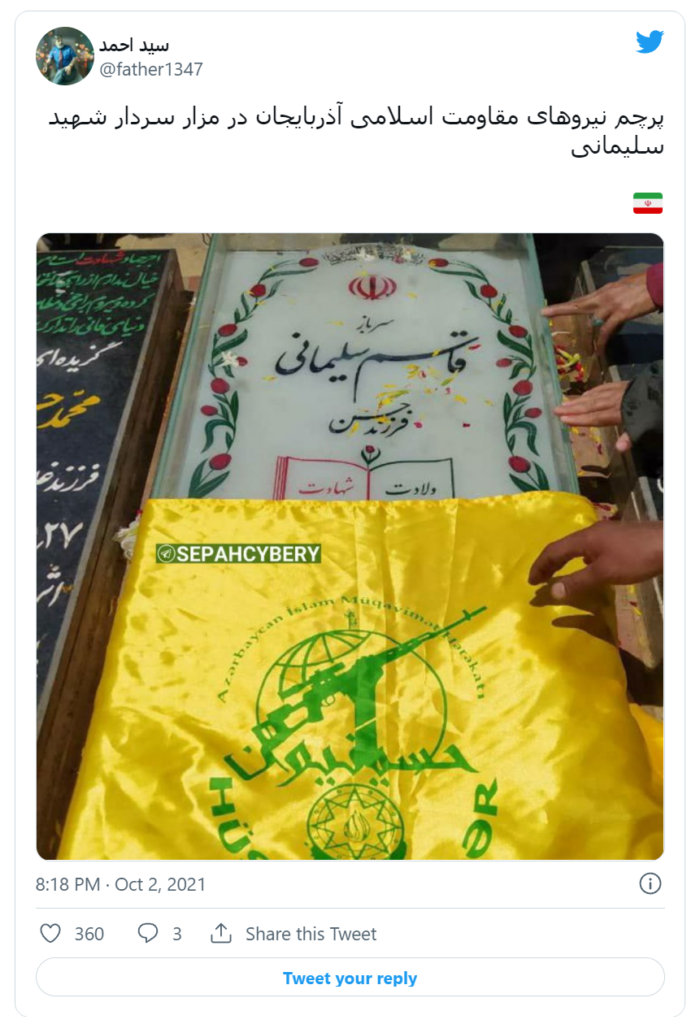

Amid the growing tensions between Iran and neighbouring Azerbaijan, several pro-IRGC accounts on social media stated that a newly-announced resistance faction has emerged in the South Caucasus republic – the Huseynyun. While next to little is known about the group – allegedly formed in 2019 during the Syrian conflict, only to be formally activated recently – the Huseynyun bears all the main hallmarks of other factions in an alliance with the Islamic Republic, known as the “Axis of Resistance”, yellow and green colour co-coordination and clutched assault rifle included.

Such developments have the propensity to bring about internal security and political instability in the resource-rich country, given that, despite being a Shia-majority country, it is still largely secular after years of Soviet rule. Critically, too, that the current government is a close and important ally of Israel and a brotherly nation to Turkey. Although Tehran has previously sought to export its revolution to Azerbaijan, it had never found much success. For example, the Islamic Party of Azerbaijan (AIP), established in 1991, the same year as the founding of the republic, was dissolved four years later, after being accused of being covertly funded by Iran with the aim of overthrowing the government and turning the country into an Islamic republic. The party remained active for several years, culminating in the 2011 arrest of party leader Movsum Samadov.

Nevertheless, the IRGC’s Quds Force has been active in Azerbaijan since the early ’90s, according to Israel’s Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Centre (ITIC). Since the country’s independence, the Quds Force: “Has engaged in subversive activities against the Azeri regime. Iran’s objectives are to destabilise Azerbaijan, to pressure its regime into changing the country’s secular character and to change its pro-Western orientation and harm its good relations with Israel.”

Some former AIP members also found their way into Azeri Hezbollah, which has existed in the country since 1993, with arms and funding from Iran and Jaysh Allah, established in 1995, and once plotted an attack against the US Embassy in Baku.

From a pragmatic perspective, Iran perceives Azeri nationalism as a threat to its own internal affairs due to the large Azeri ethnic minority in its northern Azerbaijan province. While maintaining ties with Baku, Iran has been perceived as being more supportive of Azerbaijan’s nemesis, Armenia. It is for these reasons that Iran knows it must tread carefully when dealing with its neighbour, which was once part of the Persian Empire and Qajar Iran. Iran was already seen as the biggest loser in terms of the Turkish-Russian-brokered ceasefire agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan over last year’s Nagorno-Karabakh War, with the balance of power tipped in the latter’s favour.

Yet the over-arching concern is Israel’s growing proximity to Iran’s borders via its military and political relations with Azerbaijan, which Iran, earlier this week, has been adamant that it will not be tolerating and warned against any geopolitical changes in the region. There is also the concern of the deployment of Turkish-backed Syrian mercenaries in Azerbaijan, which had been a development during the conflict last year.

It will be highly unlikely that Iran’s military drills near the border following joint Azerbaijani-Turkish-Pakistani war games last month will lead to any escalation that modern diplomacy won’t be able to defuse. However, judging by Iranian strategic thinking and foreign policy, such displays are insufficient to serve as a deterrent or to protect Iranian interests and its borders against hostile foreign elements.

As such, Tehran may find that it relies on a consistent and effective policy of funding subversive opposition groups, or supporting armed factions under the umbrella of the Axis of Resistance. For example, in 2012, Azeri authorities convicted 22 members of an illicit network handled by the IRGC who were found guilty of conspiring to carry out terrorist attacks on Israeli and Western targets. Other than Iraq, Azerbaijan, being a Shia-majority country, would be unique compared to Iran’s involvement in other countries, but also due to the progressive attitudes to religion in the country.

Yet evidently, there has been active recruitment in conjunction with Iranian interests, and religious and political sentiments are, of course, not monolithic. One undated video that circulated on social media earlier this year showed what appeared to be two Azerbaijani soldiers burning the US and Israeli flags while voicing their allegiance to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Khamenei. Any further provocations perceived by Tehran in Azerbaijan may not lead to a conflict in the conventional sense, but the emergence of the Huseynyun is an indicator that Iran has options to confront its enemies across the border in the Caucasus through unconventional means.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News