Abstract: Iran-backed militias have been scrambling to recover after the loss of their patriarchs Qassem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis on January 3, 2020. Attempts to preserve a top-down, Iran-directed system of command have met resistance, both from independent-minded upstarts like Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and the fragmenting powerbases within Kata’ib Hezbollah. To track these trends in detail and to an evidentiary level, the Militia Spotlight was stood up at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy in February 2021. This article lays out the project’s first eight months of findings, drawn from an open-source intelligence effort that fuses intense scrutiny of militia messaging applications with in-depth interviews of officials with a close watching brief of the militias. The key finding is that while the IRGC-QF (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force) still runs Iran’s covert operations inside Iraq, they face growing difficulties in controlling local militant cells. Hardline anti-U.S. militias struggle with the contending needs to de-escalate U.S.-Iran tensions, meet the demands of their base for anti-U.S. operations, and simultaneously evolve non-kinetic political and social wings.

This study builds on a series of CTC Sentinel articles since 2019 that have charted the evolution of the self-styled, Tehran-backed resistance (muqawama) factions in Iraq that direct attacks on the U.S.-led coalition. In August 2019, at the apex of muqawama political power so far, one of these authors (Knights) reviewed the manner in which the armed groups were using the legal, administrative, and funding status of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) to advance a process of state capture.1 In January 2020, shortly after a U.S. airstrike killed Qassem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the same author described the setbacks that befell the muqawama militias as they tried and failed to evict U.S. forces and quash Iraqi protests, finally losing their two iconic leaders to a U.S. airstrike on January 3, 2020.2 In October 2020, the next CTC Sentinel piece by this author looked at the manner in which Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH), the most prolific Iran-backed militia in Iraq, coped with the death of its overseer al-Muhandis.3 The January 2020 article foresaw the likely development of a roadside bombing campaign against coalition supply routes,4 which did occur in the summer of 2020,a and the October 2020 piece explored the idea that KH and other muqawama might be spawning a proliferation of “fake groups”5 (media façades used to conceal responsibility for attacks).6 The latter piece was published just as a new “conditional ceasefire”b was announced by a new coordination mechanism for the muqawama known as the Iraqi Resistance Coordination Committee (al-Haya al-Tansiqiya lil-Muqawama al-Iraqiya, or Tansiqiya for short).7 The ceasefire became a bitter issue between the muqawama factions and would be broken on multiple occasions by dissenting militiamen.

In this article, a strengthened team of analysts will take forward the story of the evolution of muqawama groups in Iraq, drilling much deeper into the internal politics and inter-muqawama politics that has shaped—and often disrupted—muqawama kinetic and information operations in Iraq in the last 12 months. As 2020 came to an end, the authors of this study assembled to form the Militia Spotlight team at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Observers were initially confused by militia use of façade groups,8 which blurred the identity of the militant actors actually undertaking attacks. To counter this, Militia Spotlight undertook content analysis of militia use of social media (Telegram and other platforms), which provided a rich stream of qualitative insights into how the groups cooperated and frequently competed.

Militia Spotlight’s online blog9 and group profiles10 were established to track this process in detail and produce evidentiary building blocks, using legal standards of proof and certainty.c The project collects militia statements in Arabic and other languages, archives evidence that may be taken offline at a later point, and uses a data fusion process to synthesize information and analyze trends. This online collection effort is strongly supplemented by the same kind of detailed interview process with U.S. and Iraqi subjects that underpinned the prior CTC Sentinel studies referenced above.11 The below analysis represents the initial eight months of top-leveld findings from the Militia Spotlight program (which began publishing analyses on February 10, 2021).

The overall story is one of increasing intra-muqawama disagreements over paths of de-escalation or escalation against the U.S.-led coalition, and of competition between the armed groups or fasa’il. As anticipated in the October 2020 CTC Sentinel analysis,12 the post-Soleimani and post-Muhandis KH has suffered significant ruptures in its leadership and perhaps in the degree to which that leadership is still trusted by the IRGC-QF.

The article starts with a concise review of militia anti-U.S. operations since January 3, 2020. Part two looks at how Iranian influence adapted during the post-Soleimani era. Part three examines how Iraqi militias tried to coordinate their actions post-Muhandis. Part four explores the difficulties between and within muqawama factions post-January 3, 2020. Part five looks at the evolution of muqawama information operations in this period. It explores apparent novelties in muqawama behavior such as the emergence of numerous façade groups used to claim operations and social media platforms, before linking these innovations to the more prosaic proprietary fasa’il networks and areas of responsibility that sit underneath all the razzle-dazzle. Part six examines the evolution of kinetic operations. In part seven, the study closes with predictions about next steps in muqawama evolution in the political, social, economic, and military spheres, with particular reference to muqawama setbacks in the recently completed October 10, 2021, elections in Iraq and their aftermath.

Below the surface of events and attacks, significant insight was gleaned from careful observation of militia communications and propaganda activities, and by interviewing officials and politicians with direct insight into the internal affairs of militia groups. The Militia Spotlight team undertakes large numbers of anonymizede interviews on an ongoing basis. When team members visit Iraq, as occurred in the summer of 2021, the conversations are substantive, usually over an hour of focused discussion on militia issues.f Alongside face-to-face interviews, two of the three authors (Knights and Malik) also undertook a dense web of communications with Iraqi interviewees using secure messaging applications, amounting to hundreds of specific information requests to verify data and multi-source points of detail, as well as secure transfer of large tranches of data and imagery. The authors use their combined multi-decade track record of interviewing Iraqis to assess information. Militia Spotlight analysis is thus the product of a synthesized open-source intelligence process.

- Overview of Militia Anti-U.S. Operations in the Post-January 3 Era

The roots of today’s operations by Iran-backed militias are often visible in the environmental factors experienced by such groups and their Iranian supporters in prior months and years. Piecing the chronology together, with hindsight, it is strongly arguable that Qassem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis were executing a strategic plan in Iraq in 2018-2019. With major combat operations against the Islamic State ended and with Iraqi elections looming in May 2018, Soleimani and al-Muhandis pushed forward on three initiatives. First, a rough plan was hatched to consolidate command and control of the PMF, including boiling down the large number of PMF micro-brigades (each well under a third of the size of an Iraqi army brigade) into a more cohesive force mostly under the leadership of KH members.13 Second, Soleimani and al-Muhandis invested huge effort in arranging the selection of Iraq’s then prime minister, Adel Abdalmahdi, who took office in October 2018.g

Third, Soleimani and Iran’s IRGC-QF (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force) began to recruit for a new resistance effort against U.S. forces in Iraq.14 As this author noted in CTC Sentinel in October 2020, new muqawama umbrella groups such as the Free Revolutionaries Front began to emerge in 2019 with the express aim of evicting U.S. forces from Iraq.15 Kinetic actions against U.S. sites and convoys were greatly intensified from May 2019 onward due to skyrocketing tension between Iran and the United States, and then again intensifiedh during the Iraqi protests that began the slow collapse of the Abdalmahdi government in November 2019 and sparked protests in Iran itself.

The pantheon of Iran-backed militias in Iraq have passed through a number of stages in the 21 months since a U.S. airstrike killed Qassem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis on January 3, 2020. The first phase was simple revenge. Iraqi militia politicians passed a non-binding motion in Iraq’s parliament to evict foreign forces on January 5, 2020, and Iran fired ballistic missiles at the U.S. site at Al-Asad Air Base two days later. A chaotic pattern of revenge rocket attacks by muqawama groups unfolded in the early months of 2020 against U.S. bases in Iraq, followed by what appears to have been Kata’ib Hezbollah’s planned vengeance for al-Muhandis, a carefully preparedi series of rocket attacks that killed two Americans and one Briton at Taji in March 2020 undertaken by KH using a new “façade”—Usbat al-Thaireen (UT, League of the Revolutionaries).16 The United States immediately struck back against KH rocket warehouses on March 13, 2020, seemingly causing no KH fatalities.17

KH seemed to accept this blow and tailor the resistance effort to less lethal harassment attacks. The main mode of resistance shifted to what became known as the “convoy strategy” against Iraqi civilian trucks servicing the coalition. Under a KH lead, often under the banner of KH’s other main façade Qasem al-Jabbarin (QJ, Smasher of the Oppressors),18 the roadside bombing campaign steadily expanded in the summer of 2020 until the number of attacks on Iraqi-manned trucks equaled those of rocket attacks on U.S. bases. Then, probably in response to intensifying U.S. threats of military and economic retaliation,19 KH announced a “conditional ceasefire” (i.e., an end to rocket attacks) on October 10, 2020, likely seeking to lower the risk of escalation until the situation became clearer in the November 2020 U.S. presidential election. The cessation of rocket attacks on the U.S. embassy in Baghdad and the Baghdad Diplomatic Security Center (BDSC) at Baghdad International airportj probably also reflected rising Iraqi public criticism of the muqawama for undertaking resistance operations in central Baghdad.k As noted, KH’s partial ceasefire was not only directly communicated but echoed by the new KH-run coordination mechanism (the aforementioned Tansiqiya, which will be discussed in detail below), which emerged to speak for the muqawama.

Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq’s dissenting role

Not all Iraqi factions went along with KH’s partial ceasefire, which represented a complete cessation of lethal attacks on Americans (because no Americans were on the convoys that the muqawama continued to strike). Militia Spotlight assessesl that Asaib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) undertook two controversial rocket strikes (November 17 and December 20, 2020) on the U.S. embassy complex in Baghdad that drew criticism from KH and appears to have been undertaken by AAH in deliberate defiance of the Tansiqiya’s ceasefire. On February 15, 2021, a new major rocket attack (again assessed by Militia Spotlight as an AAH attack20) was launched against the U.S. base in Erbil, in Iraq’s Kurdistan Region, followed by new rocket attacks on Balad Air Base on February 2021 and BDSC on February 22.22 AAH may have been seeking to assert an Iraqi leadership role of the muqawama, distinct from the IRGC-QF-directed effort.m

When the United States retaliated with deadly force on February 26, 2021, against KH and another Iraqi militia, Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada (KSS), on the Iraq-Syrian border,23 the situation changed again: KH ended the ceasefire on March 3, 2021, and initiated24 a campaign of drone and rocket attacks focused on the remaining U.S. military “points of presence.”n The accuracy of the muqawama’s first fixed-wing drone attacks allowed strikes on very specific aim-points such as U.S. intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) hangers25 and missile defenses,26 marking an apparent shift to a casualty-agnostico but nevertheless pain-inducing campaign of attrition against the U.S. presence in Iraq.p

After four months of drone attacks,q the authors understand that Iran stepped in right after the U.S.-Iraq Strategic Dialogue in Washington, D.C., and issued new guidance via IRGC-QF (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force) commander Brigadier General Esmail Qaani on July 29, 2021, to cease use of drones and rockets against U.S. bases.27 Probably driven by backchannel U.S. warnings to Iran to control the drone campaign, the Iranian demarche gradually brought about a decline in the number of drone attacks,r with the apparent outlier of one new double-drone strike on Erbil on September 11, 2021.28

The story of recent militia operations in Iraq thus seems to point to a relatively clear-cut arc of KH and AAH’s competition for control over the resistance effort. In the following section, this article will look at how the IRGC-QF sought to reduce such friction and retain sufficient control of the Iraqi muqawama groups in 2020-2021.

- How Iranian Influence Adapted in the Post-Soleimani Era

The months that followed the deaths of Soleimani and al-Muhandis saw the IRGC-QF and the muqawama adjust their internal relationships to account for the monumental loss of these two giants. Most militia leaders initially laid low within Iraqs or sheltered in Iran,29 expecting follow-on U.S. strikes. A select group of muqawama leaders visited Soleimani’s deputy and successor, Esmail Qaani, with primary favor shown to Abu Ala al-Walai of Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada and Akram Kaabi of Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba (HaN, hereafter referred to as Nujaba).30 (KH probably attended, but at that point, KH was settling its internal leadership vacuum and was not then in the habit of exposing its secretary-general’s identity in public).31 t

On the surface, little appeared to change after Soleimani and al-Muhandis died, with IRGC-QF and KH remaining the key Iranian and Iraqi players. In the first eight months of Militia Spotlight’s collection, a number of theories emerged and were tested concerning IRGC-QF’s role in Iraq, including the notion that Qaani had significantly less control of Iraqi groups (compared to Soleimani’s and al-Muhandis’ combined grip over them) and the notion of significant internecine competition within Iran’s security establishment over the Iraqi portfolio. Overall, these theories did not fully reflect the complexities of intra-muqawama and Iran-muqawama dynamics.

For instance, multiple interviewees in a position to know are unanimous that IRGC-QF still leads Iraq policy for Iran. IRGC-QF primacy in Iraq is still recognized by the Office of the Supreme Leader, Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS),u IRGC Intelligence Organization,v the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,w and Lebanese Hezbollah.x Yet, there is evidence that Qaani has less personal sway over Iraqi commanders, which is unsurprising considering Qaani’s non-fluency in Arabic and his relatively limited track record with the Iraqi muqawama compared to the more charismatic Soleimani. Some muqawama actors (notably AAH) have been serially defiant toward Qaani, seeming to grandstand whenever the opportunity has arisen to snub him. However, in most ways, Qaani follows the same playbook as Soleimani, regularly traveling to Iraq for visits that include Najaf (to meet Iraq’s clergy), Samarra (to interact with muqawama military commanders), Baghdad (to meet political and PMF leaders), and Erbil (to meet Kurdish leaders). As noted above, when Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei wished to convey a firm message to Tansiqiya commanders on July 29, 2021, he used Qaani to deliver guidance (to temporarily cease attacks on U.S. sites) rather than Iranian ambassador to Baghdad (and IRGC officer) Iraj Masjedi32 or the MOIS country chief. This underlines the strong argument that Qaani is still the channel for top-level messaging from Khamenei and that IRGC-QF still leads Iran’s policy on Iraq.

- How Iraqi Militias Tried to Coordinate Their Actions Post-Muhandis

Probably the only real innovation33 of the Qaani era is the Tansiqiya, which emerged with a widely shared public statement on the afternoon of October 10, 2020.34 In its debut statement, the Tansiqiya reiterated old grievances against the United States and recounted the muqawama’s efforts to force the alleged occupiers out of Iraq. The statement then announced a conditional ceasefire suggesting the Tansiqiya would suspend attacks in return for a clear plan for U.S. troops to leave.35 The following morning, KH spokesman Mohammed Mohi told Reuters that “The factions have presented a conditional ceasefire … It includes all factions of the (anti-U.S.) resistance, including those who have been targeting U.S. forces.” Mohi did not, however, “specify which groups had drafted the statement.”36

Tansiqiya communiques

Compared with individual militias and their propagandists, the Tansiqiya communicates in public relatively infrequently. Including the October 10, 2020, statement, Militia Spotlight is aware of nine statements. These statements tend to respond to major paradigm changes in U.S.-muqawama relations, or political events with a bearing on U.S. withdrawal. In general, topics of Tansiqiya statements relate to high-level military strategy and political affairs. Statements appear to be released on closed Telegram or other messaging groups, and are then disseminated broadly by muqawama Telegram channels. Notably, channels affiliated with KH and Nujaba are almost always the first to “break the news” of a new statement, raising the possibility that statements are released to these groups first (or exclusively).37

The Tansiqiya’s second statement38 was on February 27, 2021, and responded to the first airstrike of the Biden presidency, which targeted KH and KSS positions in Syria two days prior. The statement noted the existence of the alleged ceasefire put in place months earlier, criticizing the United States for violating it and the Iraqi authorities for allowing it to go ahead.39 In response to the February 25 U.S. strike, the muqawama militias placed themselves on a war footing. On March 3, a militia (highly likely to have been KH) launched an unusual early morning, daylight rocket attack on a major U.S. installation. A new Tansiqiya statement40 on March 4 formally ended the ceasefire and laid out new rules of engagement, saying “we are facing a new page from the pages of the resistance, in which the weapons of the muqawama will reach all occupation forces and their bases in any part of [Iraq]. The muqawama has the legal and national right and popular support for doing this … The muqawama sees confrontation as the only option.”41

The next statement came on April 6, 2021, commenting on the then-ongoing Strategic Dialogue between the United States and Iraq, laying out demands from the process and threatening further reprisals if U.S. withdrawal was delayed.42

On May 20, the Tansiqiya held a street demonstration and rally in support of Gaza (during the May 2021 conflict). As Militia Spotlight noted: “At the event, a statement was read by Nasr al-Shammari (Nukaba’s spokesperson) while Muhammad Mohi (KH’s spokesperson) stood behind him. The reading was introduced as ‘the statement of al-Haya al-Tansiqiya lil-Muqawama al-Iraqiya,’ and Shammari concluded it with the same sign-off.”43

The Tansiqiya’s next statements both related to the Iraqi Prime Minister’s visit to Washington, D.C. On July 23, 2021, the Tansiqiya laid out—in detail44—requirements for the muqawama to be satisfied of U.S. good faith in any withdrawal process, while reaffirming the muqawama’s continued intent to fight U.S. forces in the absence of any withdrawal.45 Then, as the Washington meetings concluded on July 28, the Tansiqiya criticized46 the dialogue and called for all foreign forces and aviation to be removed from Iraq, threatening aviation by noting that “any foreign flight in Iraq will be treated as hostile.”47 The Tanisiya’s most recent statements (at the time of writing) comprised an unusually concentrated burst of three post-election threats, released once the scale of the defeat of muqawama-aligned blocs became clear. The Tansiqiya used its statements to link the election results to an alleged agenda to disestablish the PMF. On October 12, 2021, the Tansiqiya reflected its shock by saying “we cannot accept” the election result, and attacked the electoral winner, Moqtada al-Sadr.48 On October 17, the Tansiqiya explicitly alleged vote-tampering by “foreign hands” with the complicity of the government and its electoral commission, requiring the commission to “correct its path” or face a “crisis.”49 On October 18, the Tansiqiya laid the groundwork for demonstrations, with the Tansiqiya adopting a firm but more measured appeal to the electoral commission and expressing solidarity with the security forces.50

Military committees

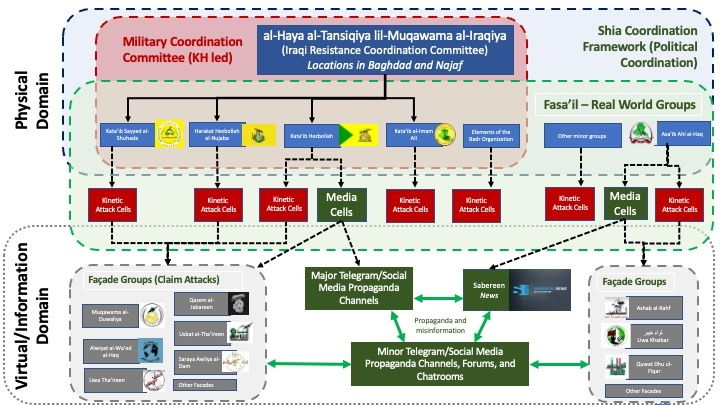

Though there have been proto-Tansiqiya type umbrellas of resistance factions since 201851 and a pan-muqawama anti-protest “crisis cell” in 2019,52 today’s Tansiqiya is a more organized model that lives up to its title as a coordination mechanism. The Tansiqiya has a small number of headquarters in which its top-level leaders typically meet. The Tansiqiya has a rudimentary de-confliction mechanism based on committees organized by region. This reflects a strong geographic territorialityy that underpins how the muqawama de-conflict their kinetic operations (to ensure synergy and avoid disrupting each other’s operations). Using geolocated attack data, Telegram claims of attribution, and other means of verification, Militia Spotlight assesses that:

A leadership committee (Militia Spotlight’s nomenclature) of a set of top Shi`a leaders from a select group of fasa’ilz meets on an as-needed basis to discuss strategy and adjust or de-conflict their activities. Kata’ib Hezbollah chairs the political committee, with a senior chairman’s role for Ahmad Mohsen Faraj al-Hamidawi (also known as Abu Hussein, Abu Zalata, and Abu Zeid), the KH secretary-general and the commander of KH Special Operations.aa

The western committee (Militia Spotlight’s nomenclature) covers Anbar and is headed by Kata’ib Hezbollah, aligning with KH’s self-styled Jazira Operations Command.53 This committee has exclusive control of attacks against the U.S. site at Al-Asad Air Base.ab

The central committee (Militia Spotlight’s nomenclature) covers Baghdad and the road systems linking Baghdad and Basra. Nujaba has some kind of coordinating authority for attacks on BDSC, while KH (during periods when attacks on the U.S. embassy are sanctioned by Iran) leads on embassy strikes from launch points in Albu Aitha, Doura, and East Baghdad.ac

KH also oversees the “convoy strategy” of roadside bombings from its Jurf as-Sakr base, south of Baghdad,ad undertaking most of the small numbers of real muqawama convoy attacks (as opposed to false claims, double-reporting, and mafia-style criminal attacks).ae

The expansive northern region (Militia Spotlight’s nomenclature), including the areas bordering the Kurdistan Region, is nominally coordinated by KSS and includes local PMF brigades linked to the muqawama such as Liwa al-Shabak/Quwat Sahl Nineveh (PMF brigade 30), Babiliyun (brigade 50), and Quwwat al-Turkmen (PMF brigade 16, based in Tuz and Kirkuk).af

AAH, meanwhile, has typically ridden roughshod over these lines, striking the aforementioned coalition annex at Baghdad airport (BDSC) and the U.S. embassy, and using its own local networks around Mosul to direct attacks on Erbil (seeming to draw upon KSS support to do so),54 and on Balad Air Base (sometimes utilizing sites where Badr is considered dominant).agAt military committee level, IRGC-QF or Lebanese Hezbollahah advisors are sometimes present to offer advice on technical aspects or operational security.ai The representatives from muqawama factions on the military committees are typically the “amni” (intelligence chiefs) responsible for the operational area in question (say, for instance, Al-Asad Air Base). An action is proposed, including a target, day and time, and this sets in motion preparatory activities such as selection and reconnaissance of an attack type, and sourcing and staging of weapons. (See the later section on kinetic operations.) In all the military regions, KH appears to be the predominant influence within the military committees, and the supposed “lead” of KSS in the north and Nujaba in Baghdad may be exaggerated or symbolic—i.e., nominally giving one region to each of the triad of most-trusted IRGC-QF partners: KH, KSS, and Nujaba.

Pre-election focus on political considerations

Another trend spotted by Militia Spotlight is the growing discomfort caused by muqawama kinetic actions that was felt by Shia politicians from large parties (like Badr) ahead of the October 10, 2021, elections. This has boosted efforts by Shia politicians to shape militia operations. The main vehicle has been the pan-Shia leadership group known as Shia Coordination Framework (al-Etar al-Tansiqi al-Shia), a talking shop of around nine majority-Shia political parties (including Badr and AAH) that has been meeting a couple of times each month since the October 2019 mass protest movement began.55 aj Indeed, the only time AAH leader Qais al-Khazali has mentioned being in the “Tansiqiya,” he explicitly referenced “al-Etar al-Tansiqi al-Shia,” not the military organ called al-Haya al-Tansiqiya lil-Muqawama al-Iraqiya.56

This political level appears to have been emphasized since the May 26, 2021, face-off between muqawama factions and the government over the arrest of a senior KH-supported militiaman, Qassem Muslih.57 Muqawama factions were embarrassedak by the episode, which publicly undermined their claim to be legal organs of the state (via their PMF role) and under the prime minister’s control. After May 26, there are multiple accounts58 that Badr Organization leader Hadi al-Ameri has played an expanded role in advising the muqawama leaders on the political repercussions of their actions.

- Difficulties Between and Within Muqawama Factions

The Tansiqiya has not been uniformly successful in marshaling the fasa’il. A key weakness has been the apparent absence of, or very weak connection to, AAH and its leader Qais al-Khazali. It is unclear if AAH was excluded or never actually wanted to join the KH-run body. There is no clear evidence to suggest that AAH ever formally joined the Tansiqiya but many indicators that AAH has instead jealously guarded and highlighted its ability to operate autonomously from IRGC-QF and to be unwilling to enter into ceasefires with the U.S.-led coalition.al AAH has even actively disrupted the ceasefire, with the balance of evidence suggesting that AAH broke the Tansiqiya’s partial ceasefire twice by rocketing the U.S. embassy in Baghdad on November 17, and December 20, 2020, coincident with Esmail Qaani transiting Baghdad to encourage compliance with the Tansiqiya’s conditional ceasefire. Then, as AAH broke the ceasefire again with a February 2021 series of rocket attacks, AAH and KH engaged in a public war of words over muqawama strategy (which Militia Spotlight termed the “Tuna and Noodles saga”59). This episode saw KH media channels criticize AAH’s rocket attacks for only damaging parked cars, and AAH media channels lampoon the KH convoy strategy for “targeting convoys of tuna and noodles.”60 In essence, both sides criticized the seriousness of the other’s resistance effort.

This sequence of February 2021 rocket strikes ended up being very consequential, triggering the new Biden administration’s use of military force in the counter-militia airstrike on February 26, which spurred the KH-led Tansiqiya to ramp up rocket (and drone) attacks on U.S. sites from March 4, 2021, onward, carrying the risk of U.S. casualties and retaliation. Even after March 4, both KH and AAH undertook parallel indirect fire attacks, with AAH sometimes appearing to pre-empt or overshadow KH operations.am

KH reliability on the decline

This post-March 4, 2021, period has highlighted new weaknesses at the heart of the Tansiqiya system. As noted, the May 26, 2021, mobilization of the muqawama against the Iraqi government center was a demonstration of the volatility and poor political instincts of KH military leaders in the post-Muhandis era, resulting in veteran militiamen like Badr’s Hadi al-Ameri being tapped to cast a political eye over Tansiqiya operations.an Yet, even this expedient showed poor results. The sharp increase in muqawama drone operations in June 2021 (11 drones used in six attacks)ao led to new U.S. airstrikes on June 27, 2021.61 Escalation continued in July, with four more drone attacks, part of a retaliatory dynamic driven by lower-level muqawama leaders.ap

In response, Esmail Qaani visited Iraq on July 29, 2021, to address both the political Shi`a leaders and the gathered military committees of the Tansiqiya (in Baghdad and Najaf, respectively). In a tough tone, Qaani delivered a message from Khamenei that urged the continuation of the conditional truce, and ordered the cessation of attacks on U.S. sites, “especially drone attacks.” Ordering the muqawama to pivot to elections preparations, Qaani warned: “Truce-breakers will be held accountable. We gave the drones and we know who has them. We can take them back.”62 As KH is the key operator of fixed-wing drones in Iraq, Qaani’s warning was undoubtedly aimed at them.aq

Against a backdrop of unprecedented public muqawama appeals to their leadership for retaliation,63 another less obvious reason for ongoing non-compliance by KH may have been the severe internal ructions being suffered within KH at the time. Coincident with Qaani’s July 29, 2021, visit, Kata’ib Hezbollah held an internal leadership vote64 for its secretary-general role, with the incumbent Abu Hussein (Ahmad Mohsen Faraj al-Hamidawi) getting only 14 votes versus 19 for his challenger,ar another KH Shura Council member called Sheikh Jassim al-Majedi (Abu Kadhim).as

Resisting a palace coup that might have had Iranian backing,at Abu Hussein did not accept the vote, splitting KH’s Shura Council and triggering extended mediation between Brigadier General Hajji Hamid Nasseri (the IRGC-QF commander for Iraq) and KH leaders.65 Amidst the KH leadership crisis, Abu Hussein’s faction within KH broke into the PMF administration department on August 7, 2021, and forced staff to hand over a full electronic register of all official and unofficial members 0f the PMF, with the stated motive of proving that AAH was being given more paid billets than KH.66 (On August 8, PMF Chairman Falah al-Fayyadh issue an internal memo that ordered guards to exclude KH members from entering the administration offices.67) These events reveal deep divisions between and within the fasa’il, schisms that Iran is struggling to manage.

- Information Operations: As Important as Kinetic Effects

One of the more novel features of muqawama activity in the post-January 3, 2020, era has been the dynamic expansion of militia activities in the information space, specifically the aforementioned utilization of numerous façade groups and media fronts. In an era of setbacks for the militias,68 the muqawama ramped up their information operationsau to offset real-world weaknesses. In fact, information operations are so intertwined with the muqawama’s kinetic and socio-political operations that it can be hard to determine at times whether information operations play a supporting role or have become the main effort. To give one example, following the arrest for murder of the KH-linked muqawama leader Qassem Muslih on May 26, 2021, the muqawama leaders quickly realized that they were not going to be able to secure Muslih’s immediate release. With great agility, the muqawama switched their focus to an information operations-led strategy to (successfully) create the public and international impression that Muslih had been released.69 Perception trumped reality, especially as the information operation was built upon the pre-existing bias in Iraqi and international observers that the Iraqi government is weak.

Key concepts: Soft war and lawfare

Two concepts appear to have shaped how the muqawama view information operations. The first is Iran’s conception of soft war (“jang-e narm” [Persian] or “harb na’ima” [Arabic]) characterized by information warfare and the development of a network of covert and overt media actors.70 In December 2020, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei laid out a framework for avenging Soleimani, highlighting the importance of “soft power” non-kinetic actions as perhaps the most appropriate response to the United States and allies.71 Earlier in 2020, Khamenei claimed that “the online space could become a tool to punch the enemy in the mouth,”72 calling those “fighting the enemy” in the online space “officers of the soft war.”73 This terminology has been echoed proudly by Iraqi muqawama activists.74

The second key concept is lawfare (“the strategy of using – or misusing – law as a substitute for traditional military means to achieve a warfighting objective”75). The muqawama expend considerable time and effort broadcasting their interest in law and their role as its defenders, while using legal arguments and Iraqi institutions in an attempt to discredit military and political opponents.76 Lawfare efforts present the muqawama as legitimate upholders of Iraqi law and sovereignty (while discrediting and effectively constraining77 av opponents). This helps maintain wider societal approval—a vital part in muqawama efforts to capture the Iraqi state. Militia Spotlight has documented the muqawama’s embrace of lawfare, and their fascination with the use of lawsuits and quasi-legal propaganda to achieve strategic ends.78 Militia Spotlight has also observed the militias’ fear of domestic and international law being used against them.79

Disinformation and deception tactics

The muqawama demonstrate considerable tactical proficiency in the information space. One tactic is the aforementioned use of façade groups, which are electronic brands (such as Usbat al-Thaireen,80 Saraya Qassem al-Jabbarin,81 Ashab al-Kahf,82 and Raba Allah83) that are used by fasa’il to issue coded admissions of their involvement in kinetic attacks. This allows the militia to enjoy the benefits of the attack (demonstrating resistance, satisfying supporters, pressuring the government and coalition) while mitigating any risks (delaying retaliation while the coalition determines the “real” perpetrator, avoiding arrest and prosecution, and dodging popular disapproval). Throughout 2020 and early 2021, façade groups used Telegramaw and other social media to claim rocket and convoy attacks in the hours following an attack event. Often the façade’s Telegram and social media platforms are created in the hours before the group’s first claim, but pre-made unique iconography of each group84 ax and the rapid growth of their media following suggests pre-preparation of façade brands for later use. Some groups have been used to claim strings of attacks, while other groups appeared for one or two attacks only before the brand name and associated media accounts fall into disuse.ay

Muqawama disinformation campaigns fall into several categories. Attacks on the U.S.-led coalition may be deliberately faked85 or accidentally overreportedaz but not corrected,86 or the impact of the attack exaggerated.ba Muqawama media also create false narratives around real events and peoplebb or fabricate entire events.bc The rapid “viral” spread of disinformation campaigns can have real-world effects: they can incite protests, further rounds of attacks, and lead to extrajudicial killings. Fake news promulgated between militia accounts is picked up by local and then international media and reported on as fact,bd contributing to wider misconception and decision-maker uncertainty. In one case, for example, the muqawama’s false narrative (that Qassem Muslih was arrested in a joint U.S.-Iraqi raid linked to maximum pressure on Iran) was re-posted on elite diplomatic message boards, where it played into the preconceptions of a very senior European diplomat and resulted in him withholding statements of support for the Iraqi government for a vital half-day window until it was proven to him that no Americans were involved (they were not) and Muslih was arrested on an Iraqi warrant for murder (he was).87 The muqawama also target Iraqis with their information operations. Muqawama propagandists have targeted Iraqi security forces with information campaigns warning them to stay away from coalition forces (lest they become collateral damage).88 Threats from infamous façade group brands like “Ashab al-Kahf” are used to threaten and coerce contract workers on military bases and embassies.89

Muqawama media campaigns also regularly cross the line between the information space and real-world intelligence activities and support to kinetic operations. Information operations channels and networks (discussed below) use their research functions as a social intelligence and targeting capability, for instance researching the social media profile of political opponents or civil society activists that the muqawama wish to intimidate, typically also researching their family, neighbors, and workplaces. When the muqawama want to muzzle an adversary or drive them out of Iraq, the information space (particularly Telegram and social media) is used to warn and threaten.be The information space is also used to target international players: for instance, threatening U.N. election workers in an attempt to reduce their freedom of movement, make some personnel leave Iraq, or discredit efforts to monitor federal elections and lay the groundwork for delegitimizing the result.bf

The muqawama information operations mechanism

In the first eight months of operations, Militia Spotlight took a close look at how muqawama information operations are organized and resourced with particular focus on which elements of the system are cooperative or competitive with each other. One top-level finding is that information operations is an area in which Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah play a very active support role. In the same manner that Lebanese Hezbollah built robust information operations capabilities in the 1990s,90 the IRGC and (in another niche contribution) Lebanese Hezbollah has provided the Iraqi muqawama with strong financial and technical assistance, often delivered through the Iran-linked Iraq Radio and Television Union91 (which is led by an Iraqi IRGC officer)bg and its parent organization, the Islamic Radio and Television Union (IRTVU).bh

In addition to the television channelsbi openly developed by the fasa’il with Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah support,bj there is now (in iNEWS TV, which is controlled by KSS)92 also a muqawama television channel that appears specifically aimed at a more liberal youth demographic. (The iNEWS TV channel employs female presenters who do not wear the Islamic hijab93 and features entertainment shows that are normally not run by Islamic channels94 in an attempt to reach beyond the current muqawama base and expose Iraqi youth to pro-muqawama narratives.)

Beyond television, the muqawama have built out a social media conglomerate in the shape of Sabereen News,95 created in January 2020, which has grown into a major propaganda and disinformation tool with more than 100,000 subscribers. The channel is a combined news service, propagandist, and social media targeting cell. The channel’s large reach allows it to enjoy significant network effects, capitalizing on information received from an array of muqawama affiliates and sympathizers. Careful observation of Sabereen’s posting patterns and content (and, equally importantly, observation of how other channels engage with Sabereen) led Militia Spotlight to conclude that Sabereen is heavily influenced by AAH.bk Militia Spotlight also views Sabereen as strongly supported by Iran, including through funding and technical assistance (arranged via Iraqi Radio and Television Union leader Sheikh Hamid al-Husseini);bl and through the basing of Sabereen servers in Kermanshah, Iran.bm The significance of Sabereen is not lost on the muqawama themselves, and Sabereen has received plaudits for its role amplifying the propaganda effect of attacks, promoting militia causes, and even operating as a kind of virtual fasa’il. In September 2021, one influential muqawama media figure heaped praise on the channel via Facebook, saying “I’m not exaggerating today if I say that the activity of Sabereen News is equivalent to a fasa’il on the ground. The channel was not satisfied with being the most prominent means of dissemination of the muqawama operations in Iraq, and so went beyond even the Palestinian media platforms to be the first channel to cover the news of the Palestinian muqawama … [Sabereen] was able to besiege and detect Zionist and American activities.”96

Meanwhile, for every “Sabereen News,” there are hundreds of mid-sized media accounts that promote proprietary militia interests on an hourly basis.bn These channels are often closely linked in with real-world fasa’il members and their kinetic activities. So-called “electronic armies” are also key players. These organizations are presented as specialists in online hacking and cyberwarfare (not unlike Israel’s Unit 8200), though in reality the electronic armies are mostly troll farms engaged in attacking opponents on social media, carrying out open-source internet research, and intimidating (and inciting violence against) opposition activists.97 Blending middle-aged veterans of kinetic operations with young tech-savvy unemployed university graduates recruited via student groups and university campuses,98 these “electronic armies”99 represent the cutting edge of Iran-backed recruitment operations in Iraq. Reaching out into all communities—Shi`a, Sunnis, Christians, seculars, and even non-Iraqis—the networks talent-spot capable journalists and influencers on platforms like Clubhouse and Twitter.100 The most successful influencers work their way up to significant stipends of $2,000-$5,000 per month and prestige items like Toyota Land Cruiser cars and even bodyguard-drivers.101

- Kinetic Operations: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

As the above section made clear, some of the outward-facing aspects of today’s muqawama operations give the sense of being a new and complex effort, while in reality the system is underpinned by the proprietary structure and resources of the individual fasa’il. In its first eight months of operation, Militia Spotlight looked deeply into the granular issues of muqawama kinetic cell recruitment, structure, de-confliction, tactics, and support functions. The picture that emerged was much more familiar and prosaic than the team initially expected. In essence, perhaps unsurprisingly, not much has changed in the way that fasa’il undertake indirect fire and roadside bombings, with the minor variation of the introduction of drones.bo The methodology developed by Militia Spotlight during eight months of trials in a real-world analytic laboratory suggests that when attributing attacks to specific fasa’il, what matters most is where the attack happens (reflecting proprietary areas of operation) and which media façade first claimed or eulogized the attack.bp

Proprietary single-fasa’il operations

Militia Spotlight assesses that attacks on U.S. sites are mostly single-fasa’il operations using that fasa’il’s own organic attack and support capabilities. Though an attack may be claimed under the name of, say, Qasem al-Jabbarin, Militia Spotlight assesses that the actual perpetrator of the operation is a pre-existing fasa’il that uses a new façade to claim its actions (i.e., that façades such as QJ are merely information operations brands without real-world kinetic branches and that no major new fasa’il have emerged in the last two years).bq

Attacks that are claimed are most often indirectly claimed by fasa’il through the use of proprietary single-fasa’il propaganda channels. This a critical indicator of the competitive and proprietary nature of the fasa’il, even those operating within the Tansiqiya. In the midst of an effort to blur their responsibility for attacks, individual fasa’il still want to individually brand attacks and claim credit in a way that is discernable to their inner circles and followers. For instance, based on sustained monitoring of Telegram platformsbr fused with other methods of collection, including anonymized interviews in Iraq, Militia Spotlight assesses that:

Kata’ib Hezbollah claims its roadside bomb attacks via its exclusive use of the Qasem al-Jabbarin brand and claims rocket attacks via its exclusive use of Usbat al-Tha’ireen brand, and has claimed drone attacks on Saudi Arabia through its exclusive use of the Alwiyat al-Waad al-Haq (AWH, True Pledge Brigades) brand.

Nujaba uses Fasa’il al-Muqawama al-Duwaliya (MD, International Resistance Faction) as a channel for exclusively claiming Nujaba attacks.

Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq exclusively uses Ashab al-Kahf (AK, Companions of the Cave), Liwa Khaibar (Khaibar Brigade), and Quwwat Dhu al-Faqar (Zulfiqar Force) to claim its kinetic operations.Teaming arrangements

In many areas, kinetic operations involve “teaming” arrangements put in place by KH to draw on the broader muqawama, albeit under KH’s strong hand. For instance, KH appears to have a monopoly on the operation of fixed-wing drone drones.bs When such systems are used, KH appears to play a coordinating role, in some cases with assistance from IRGC or Lebanese Hezbollah advisors.102 The broader logistical system that supports drone attacks uses three lines of supply: one operated by KH between Albu Kamal in Syria and the launch areas near Al-Asad Air Base, east of the Euphrates River; and two from Iran’s Ahvaz and Kermanshah regions, utilizing Badrbt and smaller KH-overseen muqawama groups with long-term ties to IRGC-QF.103

In northern Iraq, KSS seems to play a special facilitating role at the Mosul and Nineveh Plains end of a supply chain for rockets and drones, with a broader KH-overseen network moving weapons using PMF minority units from sites such as the Badr-run Camp Ashraf in Diyala and the Turkmen PMF Martyr’s Camp near Tuz Khurmatu.104

Likewise, KH runs the roadside bombing operations against convoys, and undertakes many of these attacks using their own KH Special Operations attack cells, but some attacks are undertaken in collaboration with smaller fasa’ilbu and even AAH.bv As is often the case in Iraq, there do not appear to be any hard and fast rules about who can work with whom or where, only generally observable trends that will more often be accurate than not. The key finding is that KH considers itself dominant and not the equal of any other fasa’il, a position that AAH seems to flatly reject.

- Next Steps for the Muqawama in Iraq

The post-January 3, 2020, history of the Iraqi muqawama has been largely characterized by disagreements over paths of de-escalation or escalation, and by competition between the fasa’il.bw As clearly anticipated in the October 2020 CTC Sentinel analysis, the post-Soleimani and post-Muhandis KH has suffered significant ruptures in its leadership and perhaps in its relations with IRGC-QF. As Soleimani and al-Muhandis recognized, the Iraqi muqawama is misfiring, after having grown too large, too corrupt, and too divided into personal fiefdoms. KH never played well with others, being prickly toward both foreign rivals like Lebanese Hezbollah advisors and domestic pretenders to the throne such as AAH. Today’s “big KH” (estimated at 10,000 personnel versus 400 in 2011105) is difficult to control and deeply riven by a leadership challenge to Abu Hussein. KH’s utility to IRGC-QF could eventually be supplemented or even surpassed by non-KH veteran leadersbx and smaller, better-led muqawama cells,by particularly Nujaba (and its Iran-favored leader Akram al-Ka’abi)bz and perhaps also KSS (and Abu Alaa al-Wala’i).ca

Creation of new IRGC-QF proxies?

Iranian dissatisfaction with Iraq’s greatly expanded muqawama factions has been growing for some time. In 2018, IRGC-QF appears to have begun a recruitment effortcb that targeted dedicated wala’i fighterscc who were younger, less tainted by corruption, and not known to Iraqi or U.S. authorities for terrorism offenses. These new cross-cutting cells—with names like Warithuun (The Inheritors),106 Zulfaqar (named for Imam Ali’s Sword),107 Liwa al-Golan (Golan Brigade),108 Haris al-Murshid (Guard of the Supreme Leader),109 and Fedayeen al-Khamenei (Khamenei’s Men of Sacrifice)110—recur in interviews on militia groups in Iraq (and in some open-source reporting111) but usually only in older reporting from 2018-2019. Interviews suggest that talent-spotting, team-building, and even some activation of such groups did occur and even resulted in attacks on U.S. sites in Iraq in 2019.cd

Though seemingly paused by the deaths of Soleimani and al-Muhandis, the IRGC-QF search for dependable younger fighters and their combination in new cross-fasa’il tactical cells may have recommenced. Interview material from Iraqi contacts suggests that some cross-fasa’il operations restarted in April or May 2021.112 The most common unit name associated by interviewees with these operations is “Zulfiqar.”113 ce Whereas the earlier generation of cross-fasa’il recruits seemed to work directly for IRGC-QF, today’s cross-fasa’il cells are built within the Tansiqiya military committees, involving negotiated temporary and covert secondments of some operators from supporting fasa’il to the attacking fasa’il, before returning to their original posting. The motive for this change of procedure could be operational security, as the teams do not know each other, the secondments blur attribution, and attackers can be drawn from outside the geographic area of the attack (complicating recognition by locals and CCTV).114 The same methods could be used to talent-spot operators for IRGC-QF or Lebanese Hezbollah operations, including external operations outside Iraq.115

Muqawama priorities

Reflecting on the Soleimani-Muhandis agenda in 2018-2019, one can expect some of the same objectives to be pursued in coming years, albeit with a more defensive mindset of hanging onto as many gains as possible for as long as possible. The muqawama still have considerable paramilitary clout, but they have many worries now that were far less pronounced in their heyday in the summer of 2019. The movement lacks the inspired leadership needed to herd the many ill-tempered and willful cats of the muqawama.116 The muqawama are afraid of many things: U.S. airstrikes, Israeli covert actions, arrest by the government, a clash with other Shia security forces, protestors, and the Shia religious establishment.117 The muqawama are already deeply splintered and fear greater fragmentation.118 The key thing for them now is arguably preservation of gains, not expansion.

Sustainment of the PMF structure, for instance, is absolutely critical to the muqawama. In addition to 165,000 jobscf (supporting 990,000 persons at an average family size of six119), the PMF provides numerous tangible and intangible benefits to the muqawama. One is control of bases and the right to legitimately store heavy weapons, as shown when KH rocketeers arrested on June 25, 2020, claimed that their site was a PMF base and that the rockets there were PMF munitions.120 A second benefit is the use of PMF-registered vehicles, which can pass through checkpoints and border crossings without being stopped or searched.121 A third benefit is the “get out of jail free” card that the opaque nature of PMF membership provides, namely that any individual given a PMF membership card can try to claim the right to be tried under a PMF tribunal rather than Iraqi civilian or military courts.cg The muqawama can be counted upon to rally and closely cooperate whenever the PMF structure is threatened with reduction in size or budget or privileges (such as effective impunity from Iraqi law). As most of the muqawama’s financial hustles are linked to territorial control of Iraq’s liberated areas and borders,ch the muqawama can be expected to pull together to resist removal of their garrisoning duties122 at economic hubs.

State capture or societal capture?

Since the collapse of Abdalmahdi’s ill-fated 2018-2020 government, the muqawama have become less likely to regain control of the prime minister’s office, with other Iraqi factions and international players keenly aware of the lessons of this two-year period when the muqawama effectively ruled the Iraqi state from the top.ci Though it should be expected that muqawama players will attempt to shape government formation in the wake of the recent October 10, 2021, elections,123 it is more likely that the muqawama’s main effort will be a gradualist, broad-based, and bottom-up approach to state capture—recognizing the need to adjust tactics from the days of Soleimani and al-Muhandis.

Conventional politics may not be the most promising avenue for muqawama groups to use for expansion. Their disappointing results in the October 2021 Iraqi elections—first results showing as few as 17 winners from the Badr and AAH list (versus 48 in the 2018 elections)—underline the difficulties faced by the muqawama in parliamentary politics.124 The elections also saw KH’s first political project underperform. Kata’ib Hezbollah operative Hossein Moanes Faraj al-Mohammadawi (Abu Ali al-Askari)125 formed the Harakat Hoquq (The Rights Movement) electoral list, which only secured one seat in the 2021 elections (out of 32 fielded candidates, with Moanes failing to win a seat).126 cj

Instead, the muqawama will probably now prioritize a bottom-up approach to building their political base. Kata’ib Hezbollah provides a clear example of the broadening of non-kinetic activities by fasa’il. Under the KH Shura Council, there are two powerful clusters of non-kinetic activities:

Media operations. One is an information operations-focused media cell that includes the KH media wings such as Kaf (various platforms), Kyan kF, Unit 10,000, Shabakat al-Ilam al-Muqawama, many other social media channels, and Al-Etejah TV.127

Cultural and social operations. Alongside this is the KH cultural and social wing, under the leadership of Maytham al-Aboudi. This wing includes a fast-growing civil society arm that comprises the Harakat Ahd Allah al-Islamiya (HAAI), a social and cultural foundation;ck the Sharia Youth Gathering128 and its subordinate Jihad al-Binaa employment and civic works program,cl Imam Hussein Scouts Association;129 and other cultural and sports programs;cm plus the Majlis al-Tabiat al-Thaqafiyya (Cultural Mobilization Council); the Zainabiyat women’s organization; and other cultural organizations and institutes.130 In the political sphere, KH has street vigilante movements that can be turned to protest and counter-protest activities, namely Raba Allah131 and Ahl al-Ma’arouf,132 and a cyber-arm, the Fatemiyoun Electronic Squad,133 that supports smear and intimidation campaigns against activists, media personalities, and politicians.The future of anti-U.S. operations

The muqawama’s future posture toward the U.S. military presence in Iraq is less easy to predict than their desire to cling to their advantages and build new constituencies. Since the deaths of Soleimani and al-Muhandis, Iran has sought to restrain uncontrolled escalation between the Iraqi militias and the United States. Neither Iran’s closest proxies (such as Kata’ib Hezbollah) nor its more autonomous affiliates (such as Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq) have ever been comfortable with externally imposed restraint.cn Whenever they have not been actively restrained, the muqawama have escalated, like a horse that runs faster and faster until reined in. The October 10, 2020, “conditional ceasefire” was a temporary cessation of attacks on U.S. points of presence if the United States agreed to “retreat” from Iraq.134 Badr and AAH’s Fateh Alliance welcomed135 the withdrawal of all coalition “combat forces” from Iraq by the end of 2021 that was agreed in the U.S.-Iraq Strategic Dialogue in Washington, D.C., on July 26, 2021.136 Yet Hadi al-Ameri, Fateh’s leader, outlined a maximalist interpretation of withdrawal to include all forces when he addressed the Rafidain Center For Dialogue Forum in Baghdad on August 31, 2021. Al-Ameri noted:

The era of foreign forces in Iraq is over. We are asking that now is the time for all NATO forces to leave the country, and we support the latest agreement that the Government made, and we will demand that the Government live up to the agreement. On the 31st of December, 2021, there will be no foreign forces.137

Admittedly, al-Ameri was making a televised address less than six weeks before a general election, but his comments (contrasted with his July 27, 2021, recognition of the Strategic Dialogue as “a national achievement”138) underline the contending pressures faced by muqawama leaders. At one end of the spectrum, most KH leaders reject all U.S. military presence but have also periodically honored the conditional ceasefire recommended by Iran and confined their attacks to what might be termed ‘fake resistance’co by striking only Iraqi trucks with no risk of harming Americans. This dichotomy is one factor slowly tearing KH apart.

Meanwhile, these so-called “vanguard”139 militias focused primarily on resistance activities (for instance, KH) are becoming more parochial, with their hardline vanguard elements peeling away from new non-kinetic branches focused on political, social, and economic activities. At the other end of the spectrum, the so-called “parochial”140 militias focused primarily on political and economic activities (i.e., AAH and Badr) are sometimes the drivers of rhetorical and kinetic escalation due to their domestic political and factional needs. The muqawama—the resistance—struggle with the idea of a post-resistance era in which their raison d’etre could be undermined.

Given these dynamics, any shift from Iran’s de-escalatory position, perhaps linked to a failure of U.S.-Iran nuclear talks—or a more significant loss of Iranian influence over muqawama factions—could trigger a sustained escalation of muqawama operations against the U.S.-led coalition in 2022 and beyond. Anti-coalition operations are, in reality, at a very low point today, with many escalatory courses of action at the disposal of the militias. Unless actively restrained by Iran or by Iraqi government actions, in the coming years the muqawama is likely to pose a greater threat to U.S. and Iraqi interests than it did in the 2020-2021 period.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News