Principal Findings

What’s new? Amid China’s increasing assertiveness in the South China Sea, and the deepening involvement of the United States and its allies, Vietnam is navigating a steadily thornier set of policy challenges. As the disputes intensify, the risk of armed conflict in the Sea is growing.

Why does it matter? Vietnam is a major claimant state in the South China Sea, and its views and actions can have significant impact on security there. Understanding its perspective and policy responses can help improve management of the disputes.

What should be done? Vietnam and other claimant states should accelerate negotiations to reduce the scope of their disputes, promote cooperation in less sensitive areas to build mutual confidence, bring their claims into conformity with international law and conclude a substantive South China Sea Code of Conduct as soon as possible.

Executive Summary

The risk of armed conflict in the South China Sea has risen over the past five years, as various states assert their claims to contested waters and island chains more strongly in response to China’s increasing dominance and the growing involvement of the United States and its allies. Vietnam, as a major claimant state, plays an important role in the dispute. Its actions at sea, especially following incidents of Chinese coercion, have implications for regional security. To prevent the competition over the Sea from escalating into violence, Vietnam and other claimant states should accelerate negotiations to narrow their differences and promote cooperation in less sensitive areas, such as fisheries and marine scientific research, to build trust. Ideally, they should also bring their claims into conformity with international law by declaring baselines and maritime zones that accord with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and conclude talks about a South China Sea Code of Conduct, though domestic politics in each country, and distrust among the claimants, will be difficult to overcome.

Defending national sovereignty and territorial integrity is not just the most important goal of Hanoi’s South China Sea strategy but also a central plank of the Communist Party of Vietnam’s political legitimacy. Vietnam’s long-term goal is to recover what it views as lost territories in the Sea. As geopolitical realities dictate that it put this maximalist aim on hold, Hanoi’s immediate objective is to maintain the territorial status quo and defend its waters so that it can conduct normal economic activities such as fishing and drilling for oil and gas without disruption.

Vietnam is a one-party state, and the Party monopolises decision-making on policy, lending its South China Sea approach a high degree of consistency. The Politburo and the Party’s Central Committee make policy decisions collectively, based on input from relevant stakeholders, notably the ministries of foreign affairs, defence and public security. Yet the consensus-based decision-making mechanism also means that policy changes, if any, tend to be gradual even when developments on the ground are fast-paced.

Hanoi pursues a long-term solution to the dispute through peaceful means in accordance with international law, especially the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Vietnam’s main challenge is to protect its national sovereignty and economic and strategic interests in the South China Sea in the face of China’s frequent intrusions into Vietnamese waters and its harassment of ships looking for oil and gas. The two countries engaged in a standoff in 2014, which led to deadly anti-China riots in Vietnamese cities, when China planted an oil rig in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone. In 2017, Beijing reportedly threatened to attack Hanoi’s outposts in the Spratly Islands if it did not stop drilling in an area on Vietnam’s continental shelf that overlaps with China’s expansive but ill-defined claims.

Vietnam both engages China for its own economic development and to maintain peace and stability in bilateral relations and in the South China Sea while, at the same time, balancing against the China threat. Its multi-pronged approach to China entails: upgrading its military and law enforcement capabilities; preparing for legal battles; using Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) mechanisms to rein in Beijing’s ambitions; and deepening strategic cooperation with the U.S. and other major powers. No single option can help Vietnam deal with China effectively, and only combined can these tactics offer some strategic leverage.

Vietnam’s legal and soft balancing options have brought mixed results. They have significant limitations, considering that China has flouted international law and succeeded in dividing ASEAN in the Code of Conduct negotiations. Still, although Hanoi cannot match Beijing’s military power, its steady military upgrade affords it a degree of deterrence against China’s maritime coercion. Its deepening ties with major powers, especially the U.S., Japan, Russia and India, have also enhanced Vietnam’s strategic posture in the South China Sea, though such a role comes with the risk of becoming entangled in intensifying great-power competition.

Ideally, all parties would bring their claims into conformity with international law, which would not only facilitate resolution of the dispute in the long run but also contribute to a maritime order that benefits all countries in the region. In the absence of such comprehensive easing of disputes, Vietnam and the other claimants should show greater determination to finalise their maritime boundaries and re-energise negotiations with China on a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea. Vietnam should also work with the other claimants to reduce tensions and cooperate where possible. It has had some success along these lines, settling maritime boundaries with China in the Gulf of Tonkin and its continental shelf boundary with Indonesia. More importantly, it has undertaken various joint fisheries, coast guard, hydrocarbon development and marine scientific research projects with China, the Philippines and Malaysia. Vietnam and other claimant states should leverage these experiences to come up with new initiatives to boost cooperation in areas of common interest, such as scientific research and law enforcement.

Introduction

The longstanding dispute over the South China Sea (known as Biển Đông, or the East Sea, in Vietnamese), is a major flashpoint threatening Asian and global peace and security.

The dispute concerns conflicting claims to territory and jurisdiction involving Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. Over the past five years, tensions have intensified, giving rise to concerns about an armed conflict in this crucial waterway, through which close to one third of global trade passes. Conflict risks have escalated due to the disputants’ strengthened efforts to press their claims, China’s increasing assertiveness, including its construction of militarised artificial islands in the Spratly chain, and the deepening involvement of the United States and its partners.

Vietnam is a main party to the dispute. Together with the Philippines, it has long been a “front-line state” confronting China in the South China Sea. With Beijing aggressively pushing its claims, tensions with Hanoi are on the rise. In 2014, when China planted the oil rig Haiyang Shiyou 981 in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), a standoff between the two countries lasted more than two months and prompted rioters in Vietnamese cities to burn down factories they believed to be Chinese-owned. In 2017, China reportedly threatened to attack Vietnamese outposts in the Spratlys if Hanoi did not stop its drilling at an oil and gas block near Vanguard Bank.

In 2019, a four-month showdown near the same area ended only after Hanoi withdrew a drilling rig. These incidents illustrate the combustibility of the South China Sea dispute and highlight the need for Vietnam, China and other claimant states to find mechanisms for managing their differences peacefully.

This report focuses on Vietnam’s perspective on the South China Sea. Published along with a report on Philippine views on the Sea, and an overview detailing the rising tensions between the U.S. and China, it aims to contribute to a greater understanding of Hanoi’s strategies for dealing with the dispute.

The report provides a historical overview of Vietnam’s claims in the Sea, examines the role of various stakeholders in its policymaking and discusses the implications of Hanoi’s approach for its foreign relations, especially with Beijing and Washington. It analyses the importance of three key interests – namely, territories, fisheries, and oil and gas – that shape Vietnam’s strategic thinking regarding the dispute. Finally, the report proposes policy recommendations for Vietnam and other claimant states to stop the dispute from escalating into armed conflict. It is based on open-source documents and remote interviews with serving and retired officials, scholars and analysts in Vietnam conducted in 2020 and 2021.

II. Historical Background

Vietnam’s territorial dispute with China relates to the Paracels and the Spratlys, two archipelagos it claims to have controlled for several centuries. Its claim is reflected in two white papers on the South China Sea, published in 1975 and 1988, as well as diplomatic notes and letters submitted to the UN since then.

In a note verbale to the UN dated 13 June 2016, for example, Hanoi stated that it “has ample legal basis and historical evidence to affirm its indisputable sovereignty over Hoang Sa [Paracel] Archipelago and Truong Sa [Spratly] Archipelago”.

From Vietnam’s perspective, although certain Chinese historical records mention the two archipelagos, Chinese dynasties failed to establish sovereignty over the islands.

In Hanoi’s narrative, Vietnamese dynasties in the early seventeenth century were the first to exercise peaceful, continuous sovereignty and state functions in the chains. Yet these dynasties did not establish settlements there. It was not until the 1920s and 1930s that the French colonial government, which since 1884 had represented Vietnam in foreign affairs, sent troops to occupy features in the Paracels and the Spratlys. In June 1932, the French governor general of Indochina gave the Paracels the status of an administrative unit of Thua Thien province, and in December 1933 put the Spratlys under the administrative management of Ba Ria province. In 1938, the Indochinese colonial government set up radio and weather stations on Pattle Island and Woody Island in the Paracels and a weather station on Itu Aba Island in the Spratlys.

World War II complicated Vietnam’s claims. In 1939, Imperial Japan declared that the Spratlys and the Paracels fell under its administration, seizing them from the French Indochinese government two years later. When Japan surrendered to Allied powers in 1945, the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-shek sent troops into Vietnam to disarm the Japanese and occupied the two archipelagos. On 2 September 1945, the Viet Minh under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, but Paris soon reimposed colonial rule and war broke out between French forces and the Viet Minh in late 1946. France demanded that the Republic of China withdraw its soldiers from the two archipelagos, but it was not until January 1947 that French forces occupied Pattle Island. French efforts to persuade Chiang Kai-shek’s forces to abandon Woody Island failed, but the Chinese leader withdrew the troops in April 1950. France did not fill the vacuum, and People’s Republic of China troops under Mao Zedong took over Woody Island in December 1955.

At the 1951 San Francisco Peace Conference, which formally ended the state of war between Japan and the Allies, Tokyo renounced all right, title and claim to the Spratlys and the Paracels, but did not specify to which country the two archipelagos should be returned. The delegation of the State of Vietnam, led by Premier Tran Van Huu, “solemnly and unequivocally reaffirmed the rights” of Vietnam over both the Paracels and the Spratlys.

From Hanoi’s point of view, as the islands “were already and fully part of Vietnamese territory” before World War II, they “must simply return to their legitimate owner”.

After the end of the France-Viet Minh war in 1954, the State of Vietnam left the French Union and in 1955 became the Republic of Vietnam, which controlled the southern part of the country, including the Paracels and the Spratlys. But as France withdrew its troops, Mao’s China quietly occupied the eastern cluster of the Paracels in 1956 before Vietnamese forces arrived. Faced with a fait accompli, the Republic of Vietnam government was able to occupy only the western part of the archipelago. During a naval battle in January 1974, however, mainland China seized Vietnam-held islands and gained control over the entire archipelago.

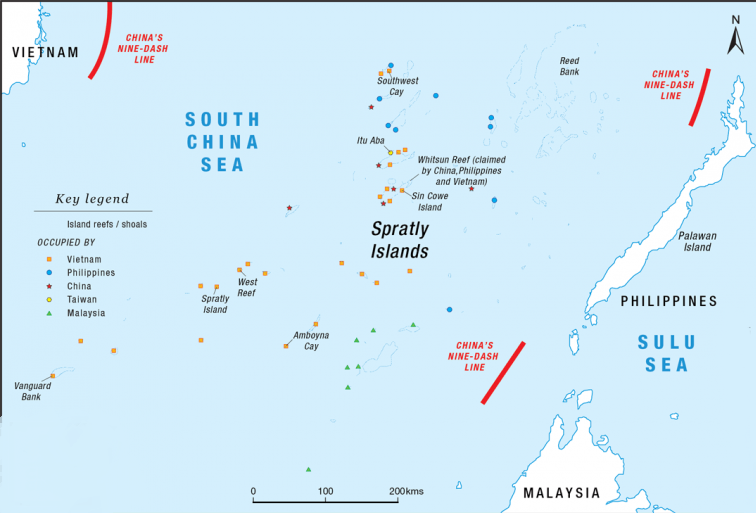

As for the Spratlys, while the Republic of Vietnam maintained its claims over the entire archipelago after World War II, it garrisoned its troops on only a few features. The Republic of China (Taiwan) continued to station personnel on the archipelago’s largest feature, Itu Aba (Taiping) Island, and the Philippine armed forces started to occupy some major land features in the archipelago in the 1960s. In the 1980s, Malaysia also took over several reefs in the Spratlys, and in 1988, mainland China established its presence for the first time by occupying eight reefs after engaging in a brief naval clash with Vietnam that claimed 66 Vietnamese lives. Brunei, the sixth state vying for the Spratlys, does not occupy any feature but claims an EEZ in the south-eastern part of the archipelago.

Since the country’s reunification in 1975, Vietnam, which adopted the name of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam the next year, has acted to protect its interests in the South China Sea, including by occupying several low-tide reefs in the Spratlys. It has published three white papers, in 1979, 1981 and 1988, to present historical and legal evidence backing its claims. From Hanoi’s perspective, historical and legal evidence proves that it holds “undeniable sovereignty” over the two archipelagos and therefore that other parties’ occupation of these features is illegal. Hanoi particularly resents Beijing’s seizures of the Paracels in 1956 and 1974, and the Spratlys in 1988. It maintains that “these are invasive acts that seriously violated the sea and island sovereignty of the State of Vietnam and infringed the United Nations Charter and international law”.

With the evolution of international law, Vietnam’s status as a coastal state and its sovereignty claims over the Paracels and the Spratlys also led it to assert control over relevant waters in the South China Sea. In May 1977, the Vietnamese government issued a statement claiming its maritime zones and continental shelf, and in December 1982, it declared the baselines from which it measures these zones.

On 23 June 1994, Vietnam’s National Assembly ratified the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). These legal foundations serve as the basis for Vietnam to enforce its maritime jurisdiction and conduct various economic activities in its South China Sea waters. It has dispatched officials to archives around the world to collect evidence to bolster its claims. It has also rebuffed attacks on its historical position.

III. The Making of Vietnam’s South China Sea Policy

The South China Sea dispute is a major policy issue for Vietnam, affecting not only its security and economic well-being but also its relations with other claimant parties and regional stakeholders.

Vietnam’s South China Sea policy rests on three pillars. First, Vietnam maintains that it has sufficient historical evidence and legal foundation to prove its sovereignty over the Paracels and the Spratlys as well as its rights to its EEZ and continental shelf in the Sea.

Secondly, it opposes the use of force and pursues a long-term peaceful solution to the dispute in accordance with international law, especially UNCLOS. Thirdly, pending such a solution, Vietnam works with other parties to manage the dispute and preserve regional stability. In addition, Vietnam’s South China Sea policy conforms with its overall defence policy, which is based on the “three nos” principle: no military alliances, no foreign bases on Vietnam’s soil and no relationships with one country to be used against a third country.

The Communist Party of Vietnam collectively makes national policy, with power concentrated in its Central Committee and Politburo. The 200-strong Central Committee is elected every five years at the Party’s national congresses. Its members normally meet twice a year to discuss and make decisions on important issues. Agendas of the Central Committee’s meetings are based on recommendations from relevant ministries, state agencies and Party organisations, but they are also sometimes shaped by Party leaders or contingencies.

As the Central Committee meets only twice a year, the Politburo, which is comprised of top Party leaders who meet more regularly, plays a more critical role in Vietnam’s decision-making. It normally convenes ahead of Central Committee meetings to shape the agenda and discussion guidelines. Members also meet on an ad hoc basis to make decisions on important contingencies. During the 2014 Vietnam-China standoff, for example, then Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung said “the Politburo’s current instruction is that the struggle [against China] must be continued in a peaceful manner in accordance with international law”, adding that it would decide when to pursue legal measures to address the dispute with China.

The Politburo and the Central Committee base their decisions on input from relevant ministries and agencies, notably the ministry of foreign affairs, the ministry of defence and the ministry of public security. The foreign ministry has long been at the forefront of Vietnam’s South China Sea cause. It disseminated white papers stating Vietnam’s case in 1979, 1981 and 1988. The ministry’s recommendations are mostly formulated by the National Boundary Commission, perhaps Vietnam’s most important source of policy input on the South China Sea dispute, in collaboration with other relevant departments, especially the Department of International Law and Treaties. The Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam, which is the ministry’s research and training arm, also provides policy advice based on its findings.

Annual conferences on the Sea co-organised by the Diplomatic Academy are high-profile events that help broadcast Vietnam’s perspectives on the dispute to an international audience.

The defence ministry provides input related to military issues, including the protection of outposts in the South China Sea, military actions by China and other claimant states, arms procurement and force modernisation. The ministry’s white papers, the fourth edition of which was published in 2019, provide not only information on Vietnam’s overall defence posture but also snapshots of its South China Sea policy.

The ministry also leads Vietnam’s defence diplomacy, an increasingly important element in its South China Sea strategy. Lastly, the General Department of Military Intelligence and the ministry’s research institutes, especially the Institute for Defence Strategy and the Institute for Defence International Relations, play important roles in formulating policy recommendations.

The ministry of public security is a lesser known yet important actor in the making of Vietnam’s South China Sea policy. A key unit is the Department of Public Security History, Science and Strategic Studies, which does research and analysis on security issues and offers recommendations to policymakers.

The ministry’s intelligence agencies also provide policy input. Its officials have attended high-profile events on regional security, for example, the sixteenth Shangri-La Dialogue held in Singapore in June 2017, where Deputy Public Security Minister Bui Van Nam headed the Vietnamese delegation and delivered a speech at a special panel on avoiding conflict at sea.

Though less visible than the foreign ministry, both the defence and public security ministries have considerable influence on South China Sea policy thanks to their intelligence channels, through which they can feed their analyses and recommendations to top leaders. A sizeable proportion of the Politburo and Central Committee members are current or former officials of these two ministries, giving them significant clout in these bodies’ deliberations on South China Sea issues.

While the foreign ministry tends to emphasise the letter of the law, security officials often accord greater weight to China’s potential reaction to any given policy. “The military and Public Security are … hypersensitive about China”, says a Western analyst.

The National Boundary Commission under the foreign ministry holds monthly meetings with representatives from sectoral stakeholders to exchange information and coordinate policy recommendations on the South China Sea. In certain cases, for instance, the national oil company, PetroVietnam, and the Fisheries Directorate play important roles, contributing knowledge collected from their field activities as well as technical information. Officials also seek scientists’ views on marine environment protection or marine scientific cooperation.

As a one-party state, Vietnam is free of the vicissitudes of electoral politics that impinge on policymaking in other claimant states, such as the Philippines, enabling it to take a longer-term approach to the dispute. Centralisation also means that Vietnam’s policies are based on consensus among various party and government branches, which allows for smooth coordination. Generational differences do exist within the Party, as do varying threat assessments, which may translate into slight divergences in thinking about China, with some older members inclined to put relations with Beijing first and some younger others more oriented toward the West.

But due to collective decision-making, shifts in Vietnam’s South China Sea policy tend to be gradual even if changes on the ground might dictate swift action.

IV. Responding to an Increasingly Assertive China

Vietnam’s South China Sea strategy is encapsulated in the motto “cooperating and struggling”, which reflects Vietnam’s hedging in its relations with China.

This strategy involves two seemingly contradictory yet complementary components: while “cooperating” with China and other claimant states on relevant issues to reduce tensions, Vietnam also “struggles” with them to protect its core interests in the Sea.

In carrying out this strategy, Vietnam combines its China engagement with balancing measures, including upgrading its military and maritime law enforcement capabilities and fortifying its outposts in the Spratlys; preparing for legal battles with China; using Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) mechanisms; and deepening strategic cooperation with the U.S. and other major powers. Hanoi began strengthening these balancing measures since around 2010, when Beijing started becoming more assertive in imposing its claims to sovereignty over land features and waters behind what it calls the “nine-dash line” in the South China Sea.

A. Engaging China

Since the late 1980s, the overarching goal of Vietnam’s foreign policy has been to maintain peace and security to facilitate economic development. Having emerged from decades of devastating wars, the country does not want another armed conflict that would disrupt its modernisation.

While determined to protect its core interests, it seeks to avoid escalations that may lead to the use of force – all the more so with its giant neighbour, which is now its largest trading partner. In 2019, bilateral trade reached $116.9 billion, accounting for 22.6 per cent of Vietnam’s total external commerce, and China was the seventh largest foreign investor in the country with 2,862 projects and $16.3 billion in accumulative registered capital. Engaging China economically and politically may not help Hanoi prevent Beijing from acting assertively in the South China Sea, but it can contribute to information exchanges, confidence building and containment of incidents.

Since 2003, the two countries have cooperated with some success in the Gulf of Tonkin, including joint coast guard patrols, oil and gas development, and fisheries management.

In May 2008, the two countries established a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership”. Under this framework, Vietnam maintains a vast network of engagement mechanisms with China, including regular visits by senior leaders, the Steering Committee on Vietnam-China Bilateral Cooperation, and various arrangements between the two countries’ government ministries and communist parties’ commissions. There are also annual meetings between provincial authorities on both sides of the border.

In the military domain, the most notable mechanisms include the exchange of visits by high-ranking officers, combined naval patrols and port calls, combined patrols along the land border, officer training programs and scientific cooperation between military research institutions.

Between 2003 and 2016, Vietnam and China conducted 60 military cooperation activities, turning Hanoi into Beijing’s sixth most frequent military diplomacy partner in the world, and the second most frequent partner in South East Asia after Thailand.

Vietnam and China conduct biannual government-level negotiations on border and territorial issues led by the two countries’ deputy foreign ministers. Three working groups under this mechanism focus on matters related to the South China Sea, namely the waters outside the mouth of the Gulf of Tonkin; cooperation in less sensitive fields, such as fisheries, marine scientific research, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief; and consultation about how to generate mutual economic development.

Through these mechanisms, the two countries maintain regular dialogues that aim to build trust and solve substantive issues, such as exploring joint development initiatives or delineating maritime boundaries.

Bilateral negotiations have resulted in some notable achievements, such as the agreements delimiting the land border and the maritime border in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1999 and 2000, respectively. These deals paved the way for establishment in 2004 of a shared hydrocarbon exploration and development zone in the Gulf of Tonkin, but no commercial exploitation has taken place.

The two countries also established a common fishery zone, with modest results. Talks on delineating the maritime border outside the mouth of the Gulf of Tonkin remain deadlocked, as Vietnam is not prepared to accommodate China’s demand to exclude the Paracel Islands from the agenda.

” Vietnam’s political and economic engagement with China is insufficient to fully protect its interests in the South China Sea. “

Vietnam’s political and economic engagement with China is insufficient to fully protect its interests in the South China Sea, due to the two countries’ “power gap”, as well as Beijing’s increasing assertiveness over the years.

Therefore, Vietnam has also resorted to balancing measures to counter China’s moves.

B. Upgrading Military and Maritime Law Enforcement Capabilities

China’s overwhelming military power presents the most serious challenge to Vietnam’s efforts to protect its interests in the South China Sea.

With much more limited resources, Hanoi is unable to match Beijing’s military might. Instead, it seeks to build up “credible deterrence capabilities” in order to make China “think twice” before staging an attack on Vietnam or seizing its territories in the Sea.

Vietnam’s 2019 defence white paper expressly states this goal:

Vietnam advocates the consolidation and enhancement of the national defence strength of which the military strength plays a core part, ensuring sufficient capabilities for deterrence and defeating any acts of aggression and war.Toward this end, Vietnam has invested significantly in upgrading its military over the past ten years. On average, between 2010 and 2018, the government spent 2.62 per cent of its GDP on defence.

In absolute terms, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimated that Vietnam’s defence budget in 2018 was approximately $5.5 billion, making it the 35th largest military spender in the world. A year later, Vietnam ranked as the world’s twelfth biggest arms importer, accounting for 2.2 per cent of the global total. In recent years, the country’s military acquisitions have focused on its navy, air force and coastal defence capabilities to better deal with threats coming from the South China Sea. Apart from these upgrades, it also invested in upgrading the capabilities of the Vietnam Coast Guard and Vietnam Fisheries Resources Surveillance, which play increasingly important roles in dealing with China’s forces in the Sea.

Most new Coast Guard and Fisheries Surveillance vessels have been assembled in domestic shipyards, in line with Vietnam’s strategy of building up its own defence industry. For some large and more sophisticated vessels, however, these shipyards use foreign designs and components. Some of Vietnam’s partners, especially the U.S. and Japan, have also provided maritime capacity-building assistance.

Such cooperation has enabled Hanoi to develop its maritime law enforcement capabilities more rapidly while mitigating pressures on Vietnam’s limited resources.

In addition to developing military and maritime law enforcement capabilities, Vietnam has also invested in defending its outposts in the South China Sea in response to China’s construction of seven artificial islands in the Spratlys.

According to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, between 2014 and 2016, Vietnam conducted land reclamation at ten features in the Spratlys, creating over 120 acres of new land, mostly at Spratly Island, Southwest Cay, Sin Cowe Island and West Reef. While the area of reclaimed land is far smaller than the estimated 3,000 acres that China has built, it has enabled Vietnam to improve its facilities and fortifications. For example, at Spratly Island, creating an additional 40 acres allowed it to extend its runway from 750m to 1,300m to accommodate larger aircraft.

” Vietnam perceives an increasing military threat from China and stands ready to defend its position in the Spratlys and the South China Sea. “

Hanoi maintains that it has not engaged in large-scale militarisation of its features, as Beijing has, and that its upgrades are mainly aimed at expanding its ability to keep watch over contested waters.

In 2016, however, Vietnam reportedly deployed to five Spratly features Israel-made EXTRA rocket artillery systems that are capable of striking runways and military installations on China’s nearby artificial islands.

It is unclear if the rockets remain in place. Regardless, the move shows that Vietnam perceives an increasing military threat from China and stands ready to defend its position in the Spratlys and the South China Sea.

C. Preparing for Legal Battles

In Hanoi’s view, keeping open the possibility of taking legal action against Beijing is consistent with its commitment to peaceful measures. In 2014, Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung asked relevant agencies to prepare documents for legal proceedings against China for illegally deploying the Haiyang Shiyou 981 oil rig in Vietnam’s EEZ.

At a conference in Hanoi in November 2019, Deputy Foreign Minister Le Hoai Trung also mentioned that although Vietnam preferred negotiations, it did not rule out other measures: “We know that these measures include fact-finding, mediation, conciliation, negotiation, arbitration and litigation measures. […] The UN Charter and UNCLOS 1982 have sufficient mechanisms for us to apply those measures”. Analysts reported in 2020 that officials were increasingly discussing the possibility of pursuing legal action. Several Vietnamese officials and scholars confirmed to Crisis Group that Vietnam has been preparing for such an option, though when and how it might proceed remains unclear.

Given China’s preference for addressing territorial and maritime disputes through negotiation, Vietnam is unlikely to settle its differences with its neighbour through the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea or the International Court of Justice.

The most feasible course for Hanoi is to use arbitral tribunals constituted under Annex VII of UNCLOS to seek a ruling against Beijing’s interpretation or application of the Convention, similar to the proceedings initiated by the Philippines against China in 2013.

Vietnam could file two separate arbitration cases, one each on the Spratlys and the Paracels, along with each archipelago’s surrounding waters. In both cases, Vietnam would seek a ruling similar to that of the arbitral tribunal in the Philippines vs. China case, especially on two points: first, that China’s claim to “historic rights” based on the nine-dash line is illegal and incompatible with UNCLOS; and secondly, that none of the features in the Spratlys and the Paracels meet the criteria of an island under Article 121 (3) of UNCLOS, and so are not entitled to EEZs.

Of the two potential cases, the Spratlys is more practical for Vietnam as the 2016 arbitral ruling for the Philippines suggests that it stands a good chance of getting a favourable award. Moreover, China has repeatedly harassed Vietnam’s oil and gas activities in its EEZ and southern continental shelf near the Spratlys. Filing a case on the archipelago could deter further such incidents.

Arbitration on the Paracels carries more uncertainty. On one hand, a ruling would likely also repeat the finding in Philippines vs. China that Beijing’s maritime claims based on the nine-dash line are illegal. In the same way the 2016 arbitral ruling states that the Spratlys cannot generate maritime zones together as a unit, Vietnam may seek a judgment that the straight baseline that China established around the Paracels in 1996, and from which it claims maritime entitlements for the whole archipelago, is against the law. On the other hand, although features in the Paracels are geologically similar to those in the Spratlys, Woody Island (213 hectares), the archipelago’s largest feature, is 4.6 times larger than Itu Aba Island (46 hectares), the largest natural feature in the Spratlys. It is therefore possible that Woody Island, unlike Itu Aba, could be classified as an island rather than a rock, thereby generating an EEZ for China which would overlap with Vietnam’s. For this reason, Hanoi may be hesitant to pursue this option.

The decision on whether or not to use the legal option against China is political.

Though Vietnam is likely to win an arbitration case against China’s maritime claims around the Spratlys, Hanoi may not take this route any time soon. In 2011, the two neighbours signed an agreement on basic principles guiding the settlement of sea-related issues, which specifies that “for sea-related disputes between Vietnam and China, the two sides shall solve them through friendly talks and negotiations”. Although the agreement does not forbid either side from seeking a legal resolution to disputes, it does require that one side has first violated the agreement, rendering it invalid, or that the side going to court has exhausted all other options.

Even if Vietnam wins the case, China’s decision to ignore the 2016 arbitration with the Philippines means that it is unlikely to acknowledge the ruling or stop encroaching into Vietnamese waters. Beijing could even retaliate, perhaps by downgrading diplomatic ties or imposing economic sanctions. China may also step up its military provocations aimed at Vietnamese assets in the South China Sea.

Although some experts have urged Hanoi to file suit, Vietnamese leaders may be concerned that a legal battle, while bringing little tangible gain, will antagonise Beijing and destabilise bilateral relations.

” Although the legal avenue remains open to Vietnam, it presents a thorny political decision that Vietnamese leaders seem unlikely to take. “

Although the legal avenue remains open to Vietnam, it presents a thorny political decision that Vietnamese leaders seem unlikely to take in the near future. Any decision to pursue litigation would have a calamitous impact on relations with its giant neighbour, so “the legal option has more utility as a deterrent”, as one observer put it.

In the meantime, Vietnam is relying on other tools to deal with China in the South China Sea, including international diplomacy.

D. ASEAN Mechanisms and the South China Sea Code of Conduct

When Vietnam decided to apply for ASEAN membership in the early 1990s, the country’s leadership was not focused on using the association’s mechanisms to push back against China in maritime disputes.

But after Vietnam joined in 1995, it made these tools central to its South China Sea strategy.

Together with other likeminded ASEAN member states, Vietnam has succeeded in keeping the South China Sea dispute high on the organisation’s agenda, thereby internationalising the issue.

It has used ASEAN to amplify its views and aimed to, in the words of a former Vietnamese diplomat, “link ASEAN’s South China Sea position to the vision of a rules-based international order”. For example, the ASEAN Leaders’ Vision Statement issued on 26 June 2020 by the 36th ASEAN Summit, held under Vietnam’s chairmanship, reaffirmed “the importance of maintaining and promoting peace, security, stability, safety and freedom of navigation and over-flight above the South China Sea, as well as upholding international law, including the 1982 UNCLOS, in the South China Sea”. Beyond strengthening an ASEAN discourse on the Sea that focuses on the primacy of international law, Vietnam has also used the association’s platforms to engage external actors on the importance of peaceful dispute resolution and to denounce China’s actions in the Sea.

Finally, Hanoi has joined other ASEAN member states in creating instruments designed to shape all the claimants’ behaviour. Vietnam and the Philippines, for example, played key roles in drafting the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea.

But in Hanoi’s view, the Declaration, which is a non-binding political document, has not constrained Beijing. It is therefore working with other ASEAN member states and China to formulate a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea that is intended to help manage disputes. Vietnam’s position is to work for a code that is “substantive and effective, in accordance with international law, especially the 1982 UNCLOS”.

On 3 August 2018, ASEAN and China adopted a Single Draft Negotiating Text to guide discussions on the Code of Conduct. The text – a compilation of nine governments’ positions rather than a negotiated consensus – shows that Hanoi is pursuing a long list of demands which it believes are essential for the code to be “substantive and effective”. In particular, it wants the future code to apply to the whole South China Sea and to be legally binding. Hanoi also seeks robust enforcement and dispute settlement mechanisms, including legal avenues such as arbitration.

It has proposed 27 additional points related to various aspects of managing the South China Sea dispute.

By the end of 2020, in part due to COVID-19-related delays, ASEAN and China had completed only the first of three planned readings of the negotiating text, a process through which parties are supposed to refine their positions and narrow their differences.

Although China is pushing the negotiation as well as the positive narrative that talks are making “progress”, Vietnam is unwilling to rush the negotiation at the expense of the code’s substance and effectiveness. Beijing favours provisions at odds with Hanoi’s preferences. For example, Beijing wants to be able to veto joint military exercises with external powers and to prohibit firms from outside the region from exploiting South China Sea resources. While Vietnam wants the code to encompass all disputed features and overlapping maritime areas, including the Paracels, China prefers to limit the geographic scope to the Spratlys. Vietnam would also like to establish a commission to monitor implementation. Vietnam is “now just trying to get ASEAN not to sign a bad deal”, commented an analyst.

Many Vietnamese analysts are pessimistic about the Code of Conduct’s prospects. As one scholar said: “The longer the negotiation, the messier things will look”.

An official added: “The code will not be very meaningful if there is no roadmap for China to comply with UNCLOS and the 2016 arbitral ruling”.

E. Deepening Strategic Cooperation with Major Powers

Developing ties with the major powers is a top priority in Vietnam’s foreign policy, bringing economic benefits and helping Hanoi improve its diplomatic and strategic posture.

But its “three nos” principle is a serious limitation on this approach, since it theoretically prevents Vietnam from entering into substantive defence cooperation. In reaction to Beijing’s growing assertiveness, however, Hanoi is increasingly open to advancing its collaboration with the major powers beyond the principle’s parameters. The 2019 defence white paper, for example, states that “depending on the circumstances and specific conditions, Vietnam will consider developing necessary, appropriate defence and military relations with other countries”. This clause offers the government some flexibility in responding to what it sees as Chinese adventurism in the South China Sea. Hanoi particularly seeks to forge stronger links to the U.S., Japan, India and Russia.

- United States

The U.S. is Vietnam’s most important bilateral partner in supporting its cause in the South China Sea, though the relationship is constrained by Hanoi’s caution about antagonising China.

As a scholar put it, “the U.S. is the only country that has sufficient material capabilities and political will to balance China, and it has also conducted actual activities in the South China Sea to challenge China’s claims”. The two countries established a comprehensive partnership in 2013, and an upgrade to strategic level is under consideration. Even without it, bilateral ties have already been de facto “highly strategic”, according to a former official, with the U.S. backing Vietnam’s position in the Sea and providing it with substantial maritime capacity-building assistance, and Hanoi quietly endorsing Washington’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy and its engagement in regional affairs.

” U.S. policy in the South China Sea is increasingly aligned with Vietnam’s preferences. “

U.S. policy in the South China Sea is increasingly aligned with Vietnam’s preferences. The U.S. regularly conducts Freedom of Navigation Operations in the Sea to challenge what it also regards as China’s excessive maritime ambitions.

In July 2020, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo denounced Beijing’s claims to offshore resources in most of the Sea and its “campaign of bullying to control them” as “completely unlawful”. Such U.S. actions enhance Vietnam’s leverage in the dispute.

Greater convergence of interests opens up new opportunities for bilateral cooperation, including Vietnam’s potential acquisition of U.S.-made arms and military equipment, its possible participation in U.S.-led regional security arrangements and the chance that it will allow the U.S. to use its military facilities. In 2018, for example, Vietnam participated in the U.S.-led Rim of the Pacific military exercise for the first time, a symbolic step forward in security cooperation. Visits by U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Vice President Kamala Harris in July and August 2021, respectively, signal U.S. enthusiasm for stronger ties with Vietnam. The main challenge for closer bilateral relations, however, is Hanoi’s prudence in promoting its strategic links with Washington due to concerns about upsetting Beijing as it seeks to maintain a balance between the two powers. Barring the unexpected, Vietnam is unlikely to permit U.S. military forces more than episodic access to its facilities.

- Japan

Japan and Vietnam established their strategic partnership in 2009 before upgrading it to an Extensive Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity in Asia in 2014.

Bilateral ties are smooth and buttressed by a high level of mutual trust. Strong economic links and convergent interests in the South China Sea serve as a foundation for cooperation. Vietnam has received significant maritime capacity-building assistance from Japan, including a $348.2 million loan to build six patrol vessels.

During Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide’s visit to Vietnam in October 2020, the two sides agreed to step up defence and security cooperation and reached an agreement allowing Japan to export defence equipment and technology to Vietnam.

More importantly, Suga stated that Vietnam was “crucial to achieving our vision of ‘the Free and Open Indo-Pacific’, and our valuable partner”, suggesting that Japan and the U.S. share a perception of Vietnam’s role in carrying out their Indo-Pacific strategies. Both countries could thus seek to enlist Vietnam in a “Quad plus” arrangement – adding it to their relationship with Australia and India. While wary of Beijing’s reactions, Hanoi may consider unofficially joining such an arrangement and participating in selected Quad initiatives to counterbalance China’s pressures in the South China Sea.

That said, Japan’s constitutional constraints and its own territorial disputes with China in the East China Sea, which are higher on Tokyo’s list of priorities, may distract it from cooperation with Hanoi.

- Russia

As the main successor state of the former Soviet Union, Russia has a long history of cooperation with Vietnam, going back to the Cold War. Russia was the first country with which Vietnam established a strategic partnership in 2001, before upgrading to a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2012. In November 2014, Moscow and Hanoi signed an agreement granting Russian warships preferential access to Cam Ranh Bay military base.

” While Russia’s presence in the South China Sea is minimal, it is still an important partner for Vietnam. “

While Russia’s presence in the South China Sea is minimal, it is still an important partner for Vietnam. Moscow is by far Hanoi’s biggest arms supplier, accounting for about 74 per cent of its total imports.

Although Hanoi has been trying to diversify its sources, Russian weapons systems remain more affordable as well as compatible with its existing military equipment. Without Russian arms, Vietnam’s military modernisation and efforts to build up deterrence capabilities in the Sea would be disrupted.

Moreover, Russia remains an important oil and gas partner. Russian companies still consider Vietnam an important market and have strong commercial incentives to maintain their operations in the country. That said, the South China Sea is not a Russian core interest. Moreover, as one expert observed, “its status as a quasi-ally of China can be a major obstacle for Russia’s engagements with Vietnam in the South China Sea”.

- India

India and Vietnam established their strategic partnership in 2007, with defence cooperation “an important pillar” thereof.

India has helped train Vietnamese submarine crews since 2013 and, in May 2015, the two countries signed a Joint Vision Statement on Defence Cooperation for the period 2015-2020, signalling commitment to greater collaboration; they anticipate conclusion of a second statement for 2021-2025. During Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit in September 2016, he offered a credit line of $500 million for Vietnam to procure arms and defence equipment from India. The two countries have been discussing India’s sale of BrahMos anti-ship cruise missiles to Vietnam since 2014. Although the deal has not been sealed, it remains a possibility given that the two countries share strategic interests in dealing with China, with which both have territorial disputes. In December 2020, Delhi and Hanoi issued a joint vision statement that pledged enhanced military-to-military exchanges, training and capacity-building programs.

Apart from military cooperation, Hanoi has also engaged the Indian oil firm ONGC Videsh Limited, a subsidiary of India’s largest public-sector company, to help with oil and gas exploration in the South China Sea, despite Beijing’s objection.

As a state-owned firm, ONGC will consider not only commercial but also strategic interests in doing its work. The company is therefore unlikely to submit to pressure from China as some private investors have.

In the coming years, as India seeks to add substance to its Act East Policy, bilateral strategic cooperation is likely to grow.

It may, however, be constrained by its limited strategic interests in the South China Sea and more pressing security issues closer to home.

V. Substantive Issues

A. Territories

Defending national sovereignty and territorial integrity is not only the most important goal 0f Vietnam’s South China Sea strategy, but a cardinal task for the Communist Party of Vietnam, which has made it a pillar of its political legitimacy.

The Party, which has long justified its monopoly of power by underlining its leadership in the country’s fight for independence and unification, continues to highlight its role in defending Vietnamese interests in the South China Sea. In an interview published in the Party’s official newspaper, a well-known scholar claimed that safeguarding national sovereignty, territorial and maritime integrity is “not only the paramount responsibility of all dynasties and political regimes, but also the most important criterion defining the dignity of the Vietnamese people”.

” Vietnam’s long-term objective remains to reclaim from China the [Paracel and Spratly archipelagos] … through peaceful means. “

Vietnam’s long-term objective remains to reclaim from China the Paracels, as well as features in the Spratlys that are occupied by both China and other claimant states, through peaceful means. Yet Vietnam understands that achieving this goal is unrealistic, not least because China refuses to participate in legal procedures to settle territorial and maritime disputes. Meanwhile, reclaiming them through military means is out of the question given Hanoi’s commitment to finding a peaceful resolution of the dispute. A more realistic option for Vietnam is to preserve the status quo, which implies maintaining its claims to both archipelagos while defending the features it controls and preventing China or other claimants from occupying new ones.

Following this logic, Vietnam proposed in Code of Conduct negotiations that claimant states refrain both from erecting new structures on islands or land features they control and from occupying uninhabited features.

A Chinese move to take over further unoccupied features would present Hanoi with a serious dilemma: either to acquiesce or confront Beijing. The best option for Vietnam is therefore to prevent such a scenario from occurring, including by mobilising international support.

In June 2012, Vietnam’s National Assembly passed the Sea Law of Vietnam, confirming the country’s sovereignty over the Paracels and the Spratlys and its rights and jurisdiction over associated South China Sea waters, in accordance with UNCLOS.

The law also provides for the development of Vietnam’s blue economy.

Another of Vietnam’s immediate interests is to deter China from intruding in its waters by building greater military and law enforcement capabilities.

In October 2018, the Party’s Central Committee adopted a strategy for sustainable development of the country’s maritime economy, which aims to make Vietnam a “strong maritime country” by 2030 by expanding industries from fishing and hydrocarbons to tourism. One measure in the Party’s resolution is to increase the military and maritime law enforcement capacity to protect the country’s sovereignty, jurisdiction and maritime rights in the South China Sea.

B. Fisheries

The fishing industry accounts for about 5 per cent of Vietnam’s GDP, generating $8.4 billion in exports in 2020. In the same year, Vietnam’s total fisheries production reached 8.4 million metric tonnes; fishing accounted for 3.85 million tonnes, while aquaculture made up the balance.

Globally, Vietnam ranked eighth in fisheries production in 2016, with the majority of its production coming from the South China Sea. By 2018, the country had 96,000 fishing vessels. Logistical support for the industry is also improving, with 82 fishery ports in operation by 2019.

Facing depleted fish stocks near shore, Vietnamese fishermen are venturing farther off the coast, sometimes trespassing into other countries’ waters. In response, these countries have adopted stern measures. Indonesia, for example, regularly seizes and sinks Vietnamese-flagged fishing boats caught in its waters, a recurrent source of tensions between the two countries.

In October 2017, the European Commission applied a “yellow card” warning on seafood exports from Vietnam, pressuring Hanoi to clamp down on illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. Vietnam has since adopted measures to prevent such illicit fishing, many of which were codified in the 2017 Fisheries Law.

Suppressing illicit fishing is, however, challenging for Vietnam as some measures could hurt the livelihood of millions of Vietnamese fishermen and their families. Efforts to clamp down on illegal activities are uneven, varying from one province to another.

The government has also considered imposing fishing bans in twenty near-shore areas during certain months of the year to cope with the decline of fish stocks caused by overexploitation.

Fisheries not only bring claimant states substantial economic benefits but also contribute to their efforts to prove their sovereign rights and jurisdiction over disputed waters. Like other claimants, Vietnam therefore promotes offshore fishing, especially around the Paracels and the Spratlys, providing subsidies to fishermen to both ensure their livelihood and bolster its maritime claims in these waters. As a scholar put it, “in a sense, fishermen are live sovereignty markers” in the South China Sea.

Vietnam also passed a law on militia and self-defence forces in 2009, which was last revised in 2019, to provide for the establishment of a maritime militia force. As of 2016, 8,000 vessels, representing just 1.07 per cent of the national seagoing fleet, had been recruited into the force.

Apart from fishing regularly, the maritime militia also gathers intelligence, assists with maritime law enforcement and coordinates with official forces in search-and-rescue missions and dealing with Chinese ships during standoffs at sea. In 2021, Vietnam established two new maritime militia squadrons. The first, set up in April, is based on the oil and gas hub of Vung Tau province in central Vietnam, with roughly 130 crew members. The second, created in June, is in Kien Giang, in the south west, facing the Gulf of Thailand.

” Incidents involving fishermen are a major source of tensions in the South China Sea. “

Incidents involving fishermen are a major source of tensions in the South China Sea. In a number of encounters at sea, law enforcement vessels of other countries have rammed, expelled or apprehended Vietnamese fishermen.

On 2 April 2020, for example, a Vietnamese fishing boat with eight fishermen aboard was rammed and sunk by a Chinese maritime surveillance ship. Apart from educating its fishermen to reduce illicit fishing incidents, Vietnam has also called on other countries to treat fishermen humanely and promoted ASEAN-China cooperation on this issue. These incidents will likely recur, however, since both Vietnam and other claimant states wish to increase their fisheries production and intend to employ fishermen in support of their territorial and maritime claims.

The fisheries sector harbours potential for cooperation among claimant states and could pave the way for high-profile arrangements in other areas in the future.

Only a few fisheries cooperation arrangements have been developed in the South China Sea, and some have been discontinued. For example, the Vietnam-China agreement on fishery cooperation in the Gulf of Tonkin expired on 30 June 2020 and has not been renewed. The two sides are negotiating a new agreement, but it remains unclear when they will be able to conclude it.

C. Oil and Gas

The oil and gas industry has contributed significantly to Vietnam’s economic development over the past 30 years. In the early 2010s, Vietnam’s national oil company, PetroVietnam, accounted for up to 20 per cent of the country’s GDP and 25 to 30 per cent of its tax revenue.

Due to declining production as well as falling oil prices, oil sales as a proportion of national domestic revenue fell from 6.61 per cent in 2015 to 3.63 per cent in 2019.

Against this backdrop, Vietnam has tried to increase its oil and gas production, for both domestic consumption and export, over the past few years. This effort has, however, been disrupted by China’s repeated harassment of its rigs and survey ships in the South China Sea.

In June 2020, Chinese pressure forced PetroVietnam to cancel production-sharing contracts with Spanish energy company Repsol for blocks 135-136/03 and 07/03. One month later, the company also nixed a drilling contract with Noble Corporation for an assignment at nearby block 06-01. The two decisions caused both financial and reputational damage to PetroVietnam.

China has also pressured international oil firms to stop their operations in Vietnam, and tried to insert into the Code of Conduct negotiating text a stipulation that littoral states must conduct all economic activity in the South China Sea, including oil and gas exploration, by themselves and not “in cooperation with companies from countries outside the region”.

This demand is onerous for Vietnam and other ASEAN claimant states with oil and gas operations in the Sea, not only because they lack the capital and technology they would need to go it alone, but also because they would have their sovereign rights and national autonomy constrained, thereby weakening their strategic positions vis-à-vis China.

Vietnam and other claimant states have attempted joint hydrocarbon development projects in the South China Sea before, but with only limited success. In 1992, Vietnam and Malaysia signed a joint development agreement, extended in 2016.

The agreement has made money for both countries, but the joint development area of 2,008 sq km is small by industry standards. In 2005, Vietnam, China and the Philippines inked a tripartite deal for a joint marine seismic survey in the Sea, but in 2008 Manila failed to renew it amid domestic political disarray. Finally, in 2006, Vietnam signed an agreement with China for joint development in a section of the Gulf of Tonkin where the boundary is delimited. The agreement has been extended several times and remains in force, though the two sides have yet to make a commercially viable discovery. Meanwhile, attempts by claimants to extend joint development to areas near the Paracels and the Spratlys have failed due to differences over how to define disputed areas.

” China will likely keep disrupting Vietnam’s oil and gas operations in the South China Sea. “

China will likely keep disrupting Vietnam’s oil and gas operations in the South China Sea, causing tensions to persist in the future. Hanoi’s options in dealing with such harassment are limited. Recent incidents show that the government usually waits for China’s provocations to abate or suspends its activities to avoid further confrontation. When necessary, however, Vietnam may choose to confront China, as it did in the 2014 Haiyang Shiyou 981 incident. Moreover, Hanoi seeks to select oil and gas partners from countries with whom its strategic interests in the Sea overlap, as these governments will logically have more incentive to back their national companies in the face of Chinese pressure.

In the meantime, Vietnam must live with persistent bilateral frictions over oil and gas, foregoing potentially considerable revenue.

VI. The Way Forward

The South China Sea is becoming an arena for U.S.-China strategic competition, presenting claimant states with challenges and opportunities.

While the dispute risks leading to armed conflict, the dangers associated with this great-power competition may nudge claimant states toward promoting cooperation and reducing tensions. China, in particular, has an interest in maintaining stability in order to minimise intervention in the Sea by outside powers. Long-term solutions, however, should start with modest, concrete initiatives in specific domains.

First, Vietnam and China should accelerate negotiations on delimitation of the waters outside the mouth of the Gulf of Tonkin. In 2000, the two countries delimited their sea boundary in the Gulf, which reduced the scope of their dispute and paved the way for substantive collaboration on fisheries and hydrocarbons. Bilateral negotiations on the waters outside the Gulf are deadlocked: China maintains that the Paracel chain can generate an EEZ of its own, while Vietnam disagrees.

Pending resolution of this difference, the two sides should consider cooperation on fisheries, scientific research or marine environment protection to build trust and promote peace in the South China Sea.

Secondly, Vietnam should expedite talks with Indonesia to delimit the two countries’ overlapping maritime claims. Hanoi and Jakarta have already agreed on the boundary of their continental shelves, which should serve as a basis to arrive at a similar understanding on their EEZs. Making this deal will require courage from leaders in both countries, who will need to face down domestic criticism that compromise means surrendering sovereignty.

But the agreement would pay off, as it would put an end to maritime disputes between the two neighbours and help reduce the number of incidents arising when fishermen from one country venture into what the other considers its EEZ. As an official said: “It’s the right time for the two parties to push their negotiation as both are facing increasing pressures [from China] in the South China Sea”.

Gradually narrowing the scope of the disputes will contribute to their resolution in the long run.

Thirdly, Vietnam should replicate its models of bilateral coast guard and fisheries cooperation at the regional level, including through minilateral mechanisms, in which a small group of littoral countries lays the foundation for wider agreement. For example, Vietnam has conducted joint coast guard patrols with China in the Gulf of Tonkin following delimitation of the maritime boundary there. The two countries could invite the coast guards of other claimant states to send ships to ward off piracy or smuggling. Considering the front-line role coast guards play in the maritime disputes, establishing regular exchanges between them could contribute both to reducing tensions at sea and building trust for cooperation on transnational maritime challenges. Similarly, Vietnam has also reached a bilateral agreement with the Philippines regarding humane handling of fishermen by law enforcement agencies. This model “should be expanded to include other littoral states or cover other areas of cooperation beyond protecting fishermen, such as conducting fisheries research or restoring fish schools”.

Fourthly, Vietnam and other littoral states should promote marine scientific collaboration to build confidence and nurture cooperation. Vietnam and the Philippines conducted four joint oceanographic and marine scientific research expeditions in the 1990s and 2000s before stopping the project in 2007, but have recently indicated an intention to revive such cooperation.

A Vietnamese official said the initiative could “leverage our experience while contributing to the reduction of tensions in the South China Sea”.

Despite an apparent regional consensus on the importance of cooperation to ensure sustainable fishing, political will remains insufficient for making the necessary arrangements. Inertia has set in among regional leaders reluctant to risk political capital on negotiations that domestic opponents could portray as leading the country to cede sovereign rights. Collaboration on scientific study of the health of South China Sea fisheries may be more politically feasible in the near term. It could lead to a scientific consensus that might, in time, help override political obstacles.

Regional officials, including former Chief Justice of the Philippines Antonio Carpio, have floated even bolder ideas. Carpio suggested in 2018 that the Philippines, Vietnam and China set rules on common fishing in Scarborough Shoal, a disputed chain of reefs and rocks off the Philippine coast.

Although it is probably too ambitious for now, claimant states could also consider, in the longer term, establishing a common fishing ground in the area between the Paracels and the Spratlys.

Fisheries might yet emerge as an area of fruitful regional cooperation.

” Vietnam and other states should bring their claims in the South China Sea into conformity with international law. “

Fifthly, Vietnam and other states should bring their claims in the South China Sea into conformity with international law. Just as China’s nine-dash line is often called illegal, some scholars contend that Vietnam’s baseline is “a bit excessive” and does not conform with UNCLOS as certain base points are too far off its coast.

While some scholars and former officials agree that Vietnam should at some point revise its baseline, it is unlikely to do so unless China drops maritime claims such as the nine-dash line or those based on the straight baseline around the Paracels. Yet even absent such steps from China, modification of Vietnam’s baseline might work to Hanoi’s advantage, in that it could reinforce norms derived from UNCLOS and generate greater international legitimacy for Hanoi’s stance. If all parties brought their claims into conformity with UNCLOS by declaring baselines and defining the extent of their maritime zones in accordance with the Convention, the scope of the Spratlys disputes would be reduced to overlapping territorial seas generated by high-tide elevations, making a solution more feasible.

Finally, Vietnam, the other ASEAN member states and China should conclude Code of Conduct negotiations as early as possible. To this end, the parties will need to narrow their differences and trade concessions where possible. Vietnamese sources evinced ambivalence about the prospective code, with most pessimistic that it would meet the oft-stated goal of being “substantive and effective”. But some believe that any agreement to which Hanoi would assent is likely to be better than no agreement at all.

For the moment, there is no good alternative to continuing to engage in the process, which remains the only forum for all of the claimants to discuss their positions.

Meanwhile, Vietnam could push for establishment of technical working groups on priority areas, such as fisheries and environment protection, to work on practical measures while insulated to a degree from the diplomatic track of the code’s Joint Working Group.

VII. Conclusion

As a main party to the South China Sea dispute, Vietnam’s perspectives matter. Its actions in the sea, whether on its own initiative or in response to moves by other claimant states, can have a significant impact on the region’s security. Within Vietnam, the South China Sea plays an important role in not only national security and economic development but also the historical narrative of nation building. Vietnam claims that it was the first country to exercise sovereignty over the Paracels and the Spratlys, thereby making it the rightful owner of the two archipelagos. Nationalist narratives cast the reclamation of lost territories in the Sea as a sacred endeavour. Beijing’s expanding footprint in these waters has spurred anti-China sentiment to run high in Vietnam. Such antipathy helps the Communist Party generate support, but it also corners leaders in uncompromising stances, complicating efforts to find common ground with other claimant states.

While seeking to resolve the dispute peacefully, in accordance with international law, Vietnam also pursues a multi-pronged approach to handle the constant challenges in the South China Sea, especially China’s coercion. This approach, best described as a hedging strategy, includes strong economic and political engagement with China, on one hand, and a range of balancing options on the other. On their own, none of these options can allow Vietnam to deal with the South China Sea dispute in general, and with China in particular. Each option has its merits and limitations, and only when combined can they give Hanoi strategic leverage. While maintaining its territorial and maritime claims, Vietnam seeks, for now, to preserve the territorial status quo and defend its waters against China’s encroachment to conduct normal economic activities. As a lower middle-income country, maintaining regional peace and stability to develop the economy remains Vietnam’s top priority.

While comprehensive dispute resolution in the South China Sea remains a remote prospect, Vietnam can contribute to a less contentious environment by accelerating negotiations with China on delimiting the border outside the Gulf of Tonkin and with Indonesia on delimiting EEZs; replicating its models of bilateral coast guard and fisheries cooperation at the regional level, especially through minilateral mechanisms; promoting scientific collaboration with other claimants and littoral states, particularly on the health of fish stocks; bringing its maritime claims into conformity with UNCLOS; and pushing for a binding Code of Conduct.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News