Many people, even politicians, do not understand the Iranian regime’s bizarre actions in relation to their nuclear ambitions or other areas. In my opinion, the main reason is there is no sociological or political analysis of a significant event. That event took place in Iran in 2019 with the uprising of the insurgent youth during which several thousand young people were killed by direct order of the Supreme Leader of Iran. With that analysis, it is possible to understand why, while Iran’s economy is collapsing and poverty is rampant, the Iranian regime refuses to negotiate.

More importantly, it explains why the current president, Ebrahim Raisi, who, according to the United Nations and Amnesty International, took part in the 1988 massacre of prisoners, has been appointed to the presidency. Together with my analyst colleague inside Iran, I tried to answer these questions through a sociological view of the 2019 uprising.

Sociology of the uprising in mid-November 2019

The November 2019 protests began with a spark of anger due to the rising gasoline prices per barrel and spread rapidly across the country. Anger quickly turned violent, and to quell it, the Supreme Leader of Iran personally ordered the Revolutionary Guards to shoot more than 1,500 young insurgents with direct fire. Thousands more were arrested. Thus, the government was able to curb the uprising. The dimensions of the uprising in mid-November 2019 were unprecedented in the 42-year life of the Islamic Republic.

The increase in gasoline prices became an excuse for the November 2019 protests, resulting from various economic, social, and political discontents. In this respect, the November 2019 protests were similar to the Lebanese protest rallies, which began with a tax spark on WhatsApp. Many Lebanese people protested against economic and political corruption in the upper echelons of government and the political system based on sectarian-religious divisions, which in practice has distorted the concept of citizenship. At first glance, those protests seem to have played an important economic role, but ultimately the political reasons have played a much more significant role.

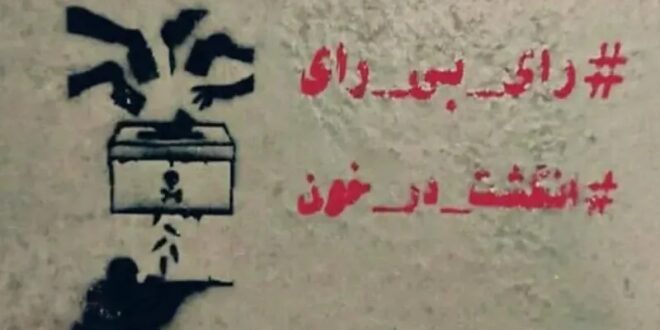

The people’s will has no role in determining the fate of themselves and their country. The government, the parliamentary elections, and the presidency are a show and sometimes a ridiculous display. Everything is in the hands of the Supreme Leader, which is well illustrated in the recent presidential election by Ebrahim Raisi. All the candidates were disqualified because of Raisi until he reached the presidency. The decisive boycott of the regime in June 1400 also confirmed this.

The Iranian regime is incapable of meeting society’s cultural and economic needs in the 21st century. From all sides, the regime seeks regional influence or the ability to create a nuclear weapon, both of which are essential for the regime’s survival. These actions have nothing to do with the demands and expectations of citizens, whose grievances include domestic and foreign policy, international relations, and regional interventions. “Death to the principle of Velayat-e-Faqih,” “Neither Gaza nor Lebanon – I sacrifice my life for Iran,” was among the slogans of this uprising.

These are the reflections of different social groups demanding profound structural economic and social changes. In situations where the use of new means of communication, such as the Internet, Twitter, Telegram, etc., has made mass mobilization easier and faster, there are situations where dissatisfaction is. The demand for a fundamental change in the 2019 uprising was apparent.

These issues divide Iranian society between the Iranian regime’s means of repression, such as the IRGC and intelligence organizations, and the rest of the nation. For this reason, the government wanted to extinguish it with direct fire at any cost. Under these circumstances, protest tools and methods, thanks to new means of communication, transform separate protest groups (such as women, workers, villagers, unemployed, or youth) into a national protest unit.

There have been many post-revolutionary mass protests. The protests between 1374 and 1376 are related to the marginalized, whose houses were destroyed by the regime’s law enforcement forces. Although these riots, especially in Mashhad, were highly motivated and mixed with violence, they were carried out by a specific group (marginalized) and related to a particular issue (house demolition). The protests of 2009, which became known as the Green Movement, had an essentially political nature, beginning with protests against election fraud and engineering. Protesters in 2009 were mostly in urban areas, especially large cities, and more than the middle class.

The protests of December 2016 included several social groups that staged large-scale uprisings in different cities of the country for ten consecutive days. Compared to 2019, political slogans were not dominant and directional. Nevertheless, they shouted their unique demands, farmers for lack of water, workers for back wages, the poor for their savings and decent jobs, others for security against the moral police, and some political slogans.

In mid-November 2019, a qualitative change in the protests emerged. In a way, that brought this moment closer to an uprising. Despite their unique concerns, various social groups (the lower classes, women, students, youth, the poor middle class, etc.) made more public and political demands. They shouted for a structural change that would impact all these areas, the overthrow of the Iranian regime. After forty years of regional interventions and nuclear ambitions at the cost of people’s livelihoods, this qualitative change was necessary. It became a factor in the maturation of this all-political demand.

Two prominent characteristics of the November 2019 uprising set it apart. The first characteristic was the uprising was organized in general and the entry of resistance units in particular. The second was the quality of the organization of the uprising that, within 48 hours, was able to expand the demands of the four decades to 162 cities.

Yadollah Javani, the political deputy of the Revolutionary Guards, said: “These events, with their breadth and dimensions, were unique in their kind during the forty years of the Islamic Revolution.”

The role of women

Another prominent feature of this uprising was the emergence of women. In many cities, the uprising was led by women and their courage and bravery. The clarity and impenetrability of this role were so prominent that the Iranian regime’s intelligence officials acknowledged it.

“The special role of women in the uprising and in mobilizing the youth and attacking the women’s mobilization centers was similar to the style of work (women Mujahideen).” (Young Revolutionary Guards media). “It is questionable why women have become the backbone of the recent unrest.” “The most important answer that can be given to this question is that the colorful presence of women has been an important factor in stimulating the feelings and emotions and zeal of society.”

(Government News Instant News Site) “Women’s mediation and fieldwork in recent unrest seems significant. In many places, especially on the outskirts of Tehran, women appear to have a special role in leading the unrest. These women in uniform each have a separate task; One of the rioters is filming, the other is blocking cars, and the other is inciting people to join the riot. It’s questionable why women have become a middle ground in recent unrest.”

The state-run newspaper “Javan,” affiliated with the Revolutionary Guards, wrote in an article entitled “Characteristics of a Riot” on November 20, 1998: “Special work was defined for women. They played a key role in attacking women’s mobilization centers and motivating young people. Although they were not killed in casualties, the style of employing women is similar to the maneuvers of the Iranian regime’s (Mojahedin) opposition’s sworn opposition.”

In recent years, Maryam Rajavi, the leader of the Iranian opposition, has enjoyed widespread support among Iranian youth and women in Iranian society, relying on her ten-point plan to separate religion from the state, freedom of dress, and to oppose any discrimination against women. According to intelligence officials, Maryam Rajavi has taken to the streets.

The anger accumulated over the years cannot be dispelled, particularly toward specific institutions of Iranian life. Banks are indicators of people’s exploitation. The non-return of people’s reserves continues under the pretext of bankruptcy of police stations and other government places.

A class study of the 2019 movement

The lower middle class played a significant role in the recent protests of January 2016 and November 2019. To be more precise, November 2019 was the intersection of the protests of the urban poor and the lower middle class. Driven into poverty, the middle class has always protested and is fundamentally conflicted, theoretically and in reality. Members of this class are often educated and even have university degrees. Most of them know what is going on in the world. They are well aware of the technology of social networks and their use. These individuals aspire to return to the middle class.

Meanwhile, these same people have economically joined a part of the urban poor. Sociologically, these people belong to the world of academia, the Internet, books, and intellectuals, but financially, they are in absolute poverty. Most are unemployed or engaged in low-income and unstable jobs, generally unrelated to their specialization and education. Despite the many resources available in their country (such as national wealth, oil, mines, reservoirs, etc.), most people know they are deprived of even the minor blessings of life. Hence, these people carry anger, feel very oppressed, and hate the unjust treatment.

“At present, the class gap is seen in such a way that we see two classes today; One class is made up of the rich, and the other class is made up of the poor. As a result, the middle class seems to have fallen to the lower classes.” (Jahan Sanat government newspaper on November 8)

Organization of the protest movement

The young newspaper, the Revolutionary Guards, wrote on November 20, 2019, about the characteristics of the uprising: “Organized violence was one of the unique features of the recent unrest. Dozens of police stations, the IRGC, and the Basij were attacked with firearms, and several Basijis were surrounded and killed.”

The essential features of the November 2019 uprising are:

The presence of the most deprived sections of society who stood against the repressive machine of Velayat-e-Faqih.

The uprising’s speed, divisiveness, and radicalism quickly manifested themselves in the burning of banks and the destruction of government symbols.

The uprising quickly targeted the union demands with the slogan “Death to Khamenei,” the head of the regime, and had a subversive character.

The organization of the insurgent forces, the main focus of which was the youth and the resistance units.

The role and performance of women leaders were prominent in all scenes.

The extent and dispersion of the uprising spread to 1,000 points throughout the country in the shortest time.

Testing the strategy of returning resistance units in cities.The Power of a Protest Uprising

The power of a socio-political or protest movement in creating costs (material and immaterial) to the government must be seen here. Even a blow to the credibility of a government (intangible cost) is an example of the power of a protest movement. The 2019 movement was so powerful that it questioned the legitimacy of the Iranian regime in the international arena. That was the most significant blow to the regime, so the subsequent events and strategies of the Iranian regime reflect the impact of this blow. It is safe to say that even the regime’s actions, including its procrastination in the nuclear talks and the appointment of Raisi as president, all stem from this uprising.

Consequences of November 2019 – the unification of the regime

Following this fatal blow, the Iranian regime, which is well aware of the social fault and can move at any moment, is turning its back on one piece. There were two major factions within the Iranian regime, the fundamentalist faction, and the Madra faction. The Iranian regime was forced to operate in the Madraa faction. On the other hand, by instigating the illusion of change, they had established a policy of Western appeasement with Iran. Every move now is meant to limit or stop uprisings in their tracks.

Therefore, we see that the Supreme Leader of Iran forbids the import of a valid vaccine from the United States, Britain, and France to spread despair during the COVID-19 pandemic to distract from the other issues that ferment uprisings.

Conclusion

The 2019 uprising has put the Iranian regime at a dead end. Suppose the Iranian regime wants to continue its regional influence and achieve an atomic bomb or the development of its missiles at the cost of the Iranian people. The international community wants the Iranian regime to renounce regional influence and acquire nuclear weapons, which is very unlikely. Eventually, the regime will not sustain its regional influence, terrorism, and repression so that it will collapse.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News