As Arab states prepare to reconvene this March for the 37th Arab League Summit in Algiers, one topic looms large over the agenda: the readmission of Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, expelled in 2011. An increasing number of regional players have thrown weight behind Syria’s return, both traditional Syrian allies like Algeria and Iraq, and more notably, the once-hostile United Arab Emirates and Jordan. In response, Arab League Secretary-General Ahmed Aboul Gheit posited that Damascus may well regain its seat–if consensus can be reached among all Arab nations.

To some observers, this level of engagement with Syria may come as a surprise. Despite private discussions on Syria’s rehabilitation ahead of the last Arab League Summit in Tunis, nearly three years ago, debate on Syria’s potential return was ultimately not placed on the official summit agenda. Yet, the same heavyweights behind those closed-door talks, namely Egypt, the UAE, and Jordan, have returned to the forefront in 2021, after engaging in a flurry of meetings, negotiations, and agreements with Damascus. Given this continuity, recent Arab reengagement with Syria should not be seen as a sudden change of heart. Rather, it represents the crescendo of geopolitical trends that have been slowly gaining traction since 2016.

While many Arab states have begun the process of normalization with Syria, each is doing so at a different pace. This pace reflects not only the varying challenges and opportunities détente with Syria brings for each state, but also the varying degrees of leverage al-Assad holds over his interlocutors. So far, Damascus has managed to carve out significant economic lifelines, while bolstering its international legitimacy–all without making any serious concessions. In this sense, the al-Assad regime has already achieved a significant degree of regional rehabilitation, albeit tentative and informal. Readmission to the Arab League in March would more formally recognize al-Assad’s international legitimacy, and serve as an important symbol of Syria’s return to the Arab fold. It remains to be seen whether Arab states, as well as their extra-regional allies, will be willing to take such a step.

Syria on The Path to Normalization

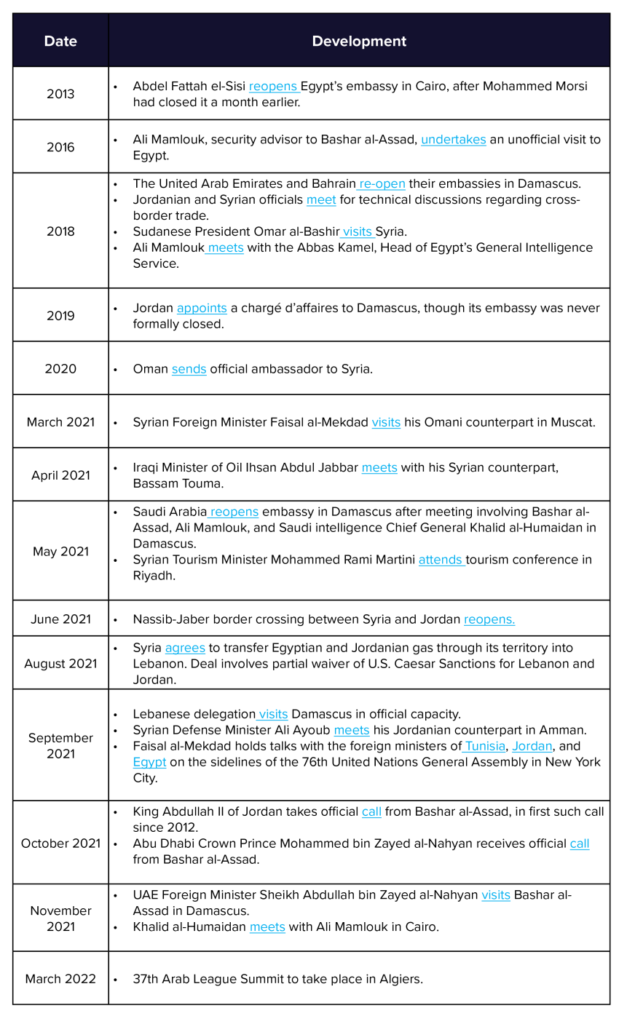

Responding to a wave of direct engagement between Syrian officials and their Arab counterparts over the past year, which included an unexpected agreement to reopen the moribund Arab Gas Pipeline, many observers proclaimed the end of Syria’s international isolation, especially with respect to key Middle Eastern neighbors. Such analysis obscures the fact that a number of regional players began reestablishing ties with Damascus years before any of its recent diplomatic triumphs. As Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal al-Mekdad stressed amid great acclaim over the historic October 3rd phone call between the Jordanian King Abdullah II and Bashar al-Assad, Arab states’ change in approach towards Syria “began a long time ago,” with shifting regional dynamics convincing Arab nations that “Arab solidarity” was required to overcome the region’s challenges. The litany of moves towards normalization, detailed below, represent years of dialogue, planning, and strategic realignment by the region’s main actors.

Selected Key Developments in Arab Reengagement with Syria

Shared Factors Driving Arab Normalization

In justifying the initiatives detailed above, many of the region’s players have cited similar concerns. Almost all have noted, both publicly and privately, their desire to reduce Iranian influence in the country, seeing Arab isolation as a strategy that has only further entrenched Tehran in Damascus. Regional states’ growing ties with Russia have also likely encouraged normalization, considering Moscow’s vested interest in restoring Damascus’ international legitimacy. At the same time, regional engagement has targeted Turkey’s interventionist policies in northern Syria. However, unlike that of Iran, Turkey’s involvement does not significantly contribute to ongoing struggles over Damascus’ geopolitical orientation; multiple analysts believe that Ankara and Damascus’ shared fears of the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria will ultimately lead to a reconciliation between al-Assad and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. As such, the Turkish role in Syria is likely a secondary concern for Arab players, especially in the midst of recent moves towards rapprochement between Ankara and Abu Dhabi, Cairo, and Riyadh.

On the more practical front, Arab engagement also promises increased regional stability, which in turn, permits the connectivity necessary for Syria to resume involvement in neighboring economies. Dr. Joshua Landis, Syria expert at the University of Oklahoma, tells FPRI that Lebanon’s economic collapse has further driven reengagement: “[it] added urgency to the need to revitalize the economies of the region,” –a daunting task unreachable so long as Syria remains isolated. Relatedly, countries across the region have all expressed interest in taking part in the lucrative reconstruction opportunities that al-Assad has dangled, with Emirati, Jordanian, and Lebanese officials all pressuring Washington to waive U.S. sanctions restricting such investment. Finally, regional actors share concern over increased drug smuggling. The Syrian regime and various Iranian militias significantly ramped up production of amphetamine-type pills like Captagon in 2018, resulting in substantial addiction problems across the region.

Given these mutual interests, it is tempting to interpret varied instances of Arab normalization with Damascus as the emergence of a united, anti-Iran, Sunni-Arab axis. However, that Arab nations are neither normalizing at the same pace, nor in total agreement on various Syria-related issues, complicates any such assumption. To better understand the existence and nature of such divergences, it is necessary to analyze the motives and timing of each state’s engagement with the Syrian regime.

Egypt

Egypt was arguably the first, major Arab player to reengage with the Syrian regime. It has opted for steady dialogue with, and at times outright public support for, Bashar al-Assad, ever since Abdel Fatah el-Sisi’s assumption of the presidency in 2013. Dr. Ezzedine Choukri Fishere, a former Egyptian diplomat now teaching at Dartmouth College, tells FPRI that Cairo’s stance should not be surprising. “Traditionally, Egypt has viewed Syria as a cornerstone of its Arab policy,” says Fishere, “and it understands that even if it disagrees [with Damascus] on regional policies, Syria is crucial to regional stability.” According to the ex-envoy, Cairo and Damascus see eye to eye on threats posed by the Arab Spring, political Islam, and the Muslim Brotherhood, ensuring that bridges connecting the two remain intact, buttressed in particular by the deep, historic relationship that exists between their respective military establishments. When other regional players began making overtures to Damascus in late 2018, for example, Syrian and Egyptian intelligence chiefs had already met at least twice. The nature of the two countries’ ties has been made clear through Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry’s repeated framing of Egyptian-Syrian cooperation as part and parcel of “Arab national security.”

Cairo may also see Damascus’ regional reintegration as a boon to its geopolitical position. The resurgence of an authoritarian, Arab-nationalist, nominally-secular Syrian republic, once an influential player in the region, would provide legitimacy to Egypt’s own political system and geostrategic orientation, according to Giorgio Cafiero, CEO of Gulf State Analytics. However, it is likely that Egypt will exercise caution in its rehabilitation of Damascus; it does not seek to significantly strengthen al-Assad and his confrontational, revisionist approach to foreign policy. In the eyes of Dr. Fishere, Egypt aims to serve as a moderating influence over the Syrian president, “putting Syria where it was under Hafez al-Assad in the 1990s: a junior partner of Egypt that is at least open to peace with Israel and getting along with the U.S.” In what appears to be an effort to exert such influence, Egyptian officials have demanded that Cairo become the “Arab leader” in any political resolution in Syria.

United Arab Emirates

Ever since the UAE’s decision to re-open its embassy in Damascus in 2018, Abu Dhabi has stressed the necessity of re-establishing an “Arab presence” in Syria, one that would serve to prevent further “regional interference,” by Iran in particular. By 2018, Russia had convinced the UAE that Arab engagement would decrease Syrian dependence on Iran, while simultaneously giving it a foothold in Damascus. Bassam Barabandi, a defected Syrian diplomat, has argued a similar line in explaining both the recent call between the UAE’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed al Nahyan and Bashar al-Assad, and the visit of Abu Dhabi’s foreign minister, the crown prince’s brother, to Damascus. Barabandi believes that the UAE, in coordination with Moscow and Tel Aviv, is actively seeking to weaken the role of Iran and its proxies.

Though many analysts question whether al-Assad could, or would, allow such a shift, Giorgio Cafiero points out that the UAE has significant leverage over the Syrian president. Unlike Tehran, or even Moscow, Abu Dhabi remains the only country currently engaged with Damascus that has the financial capacity to cover its estimated $250-400 billion reconstruction tab. This capacity may well explain why the UAE moved to normalize so quickly. It is not a stretch to imagine that this early engagement has facilitated the rebooting of economic ties, exemplified by a recent meeting between the economy ministers of Syria and the UAE on the sidelines of Expo 2020 in Dubai. Initial returns from such engagement emerged only a week later, in the form of an agreement on the construction of a 300-megawatt solar power plant in Rif Dimashq, to be carried out by a consortium of Emirati companies.

Jordan

With Jordan sharing a 362-kilometer border with Syria, it is no surprise that Amman’s outreach towards Damascus has sought to address outstanding, spill-over effects from the Syrian Civil War. In September of 2018, officials from Amman and Damascus were already engaged in technical discussions to reopen the Nassib-Jaber border crossing, whose closure had impacted both trade and security cooperation. After the Syrian regime regained control of rebel-held Daraa on September 8th, Jordan’s army chief was quick to invite Syrian Defense Minister Ali Ayoub to Amman, seeking assurances that Iranian factions would not operate in border areas. Relatedly, Jordan has also been hoping that direct engagement and border cooperation can reduce the illicit smuggling of Captagon.

Amman also looks at normalization as a much-needed economic boon. Having reopened cross-border trade by land and air in recent months, Jordanian officials are pushing for a return to pre-war levels of bilateral trade. In 2011, exports to Syria raked in over $615 million dollars, compared to a paltry $67 million in 2020. Figures from a Syrian cargo syndicate recently confirmed that the volume of Jordanian exports to Syria has already increased six-fold in comparison to years past. Looking beyond domestic economic growth, Amman also seeks to alleviate the economic and energy crises in Syria–crises that need to be solved before Jordan’s estimated one million Syrian refugees, long a burden on the Jordanian economy, can return to their homeland. In explaining why Jordan waited until 2021 to restart this economic cooperation, Dr. Joshua Landis cites the change in U.S. administration. “President Trump’s team was keen on isolating Syria and expanding sanctions as much as possible,” he notes, which precluded Amman from active engagement. Once Joe Biden took office, bringing with him a more hands-off approach to the region, King Abdullah II was quick to organize a July 19th visit to the White House, at which he allegedly pressured the president to waive U.S. sanctions that had restricted Jordanian-Syrian economic links.

Saudi Arabia

Despite ostensibly holding similar interests to those of the UAE, Saudi Arabia has only recently embarked on the path that its close ally began almost three years ago. In explaining the delay, both Saudi and Syrian analysts have noted that a significant portion of the Saudi political elite, let alone the masses, remain vehemently opposed to the al-Assad regime, citing grievances going as far back as Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri’s assassination in 2005. As such, even now that officials from Riyadh and Damascus have resumed bilateral contacts, Riyadh remains reluctant to openly support Syria’s return to the Arab league, reserving any such sentiment for private meetings.

There are different narratives contending why Saudi Arabia renewed dialogue with Syria. Many analysts argue that Saudi engagement is inspired by the same logic as its Gulf allies, focused on reducing the number of Iranian militias and strategic military assets in the country. However, according to an official in the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs who had knowledge of talks with Riyadh, Saudi engagement may also be an attempt to defuse tensions with Tehran, in the spirit of recent Saudi-Iranian moves towards rapprochement. Whatever the case, it should be noted that Saudi Arabia’s shift in approach was not a total surprise, given Bahrain’s decision to reengage with Syria in 2018. Manama’s foreign policy initiatives have traditionally required consent from Riyadh, and are therefore often considered indicators of potential Saudi moves.

Syria

Thanks to these normalization initiatives, Damascus has bolstered its international legitimacy, increased its leverage vis-à-vis Tehran, and secured crucial installments of cash and gas in return for the transport of Egyptian and Jordanian gas to Lebanon (though this deal is still pending technical works, and a formal U.S. green light). Such achievements have been widely hailed as a coup for the al-Assad regime, given its previous isolation. Yet, it would be naïve to assume that the Syrian president has had no role in bringing the region’s players to the table. Though Syria is often presumed to have little leverage over international actors, given the litany of crises it faces, and its near-complete dependence on Moscow and Tehran, recent developments challenge such thinking. By skillfully leveraging the Iranian presence in Syria and Lebanon, along with the Captagon issue, al-Assad has in fact managed to play a driving role in shifting regional attitudes and policies towards his regime.

It remains true that many analysts see al-Assad’s pledges to reduce the Iranian presence in Syria as a bluff. According to Muhammad Sarmini, an advisor to the oppositional Syrian Interim Government and founder of the Istanbul-based Jusoor for Studies think-tank, everyone in the region knows perfectly well that the Syrian regime does not have the capacity to expel, or even restrict, Iran’s activities, especially in the near future. “Arab countries’ justifications–whether officially or unofficially–that normalization with the regime will push it to expel Iran from Syria are no more than propaganda,” he tells FPRI. At the same time, Washington and its Arab allies may still be holding out real hopes that, in the long run, Tehran’s foothold in Damascus may loosen. As Mr. Sarmini points out, “Arab normalization and economic engagement with the regime can lead to the weakening of Iranian interests, without this implying that Iran will eventually be pushed out of Syria. Any contracts that Arab companies will obtain will be at the expense of Iranian ones.”

Furthermore, an eventual decrease in Iran’s military presence within the country still remains a possibility. Damascus has been uncharacteristically mute in response to dozens of Israeli strikes on Iranian positions in Syria, allegedly coordinated with Moscow. Dr. Andreas Kreig, of King’s College London’s School of Security Studies, stated that Tehran may be “more flexible” on its positions in Syria than those in Iraq or Lebanon. Indicative of this notion was al-Assad’s alleged personal order to remove Iran’s top military chief in Syria, Javad Ghaffari, which incidentally came amidst a sizeable reduction of Iranian militiamen across the country.

Even if the president himself remains reluctant to challenge Iran, as some experts maintain, a Syrian official recently revealed to Al-Monitor that a significant camp within the Syrian regime has been pushing to diminish Tehran’s role in Syrian affairs. Notably, this faction is headed by none other than First Lady Asma al-Assad, a preeminent power broker within the Presidential Palace. Muhammad Sarmini corroborates Al-Monitor’s report, noting that figures within this coterie can be found across the Syrian state and its institutions, “work[ing] in cooperation with the Russians and other actors (including the UAE) to curb Iranian interests.” Importantly, he adds, “[this camp] is popular even within the pro-regime popular base, which sees the Iranian role as a threat to its social and political culture.” Examples of this threat include Shi’a proselytization initiatives among the traditionally liberal Alawite community, and Iranian charitable institutions’ linking of aid to the imposition of certain Shi’ite doctrinal teachings.

Meanwhile, the Syrian regime appears to be dangling the Lebanon file in a similar fashion, offering Arab states yet another way to contest Iran’s influence in the Levant. According to some analysts, a major inspiration for the Arab Gas Pipeline deal was Egypt and Jordan’s conviction that Syrian gains in Lebanon decrease Iranian leverage, not only within Beirut, but also with the greater Arab world. Marc Ayoub, of the American University of Beirut’s Issam Fares Institute, has even argued that by strengthening Iran’s position in Lebanon–allowing its oil tankers transit through Syria–al-Assad “pushed [the deal] forward.” Lest the Arab position in Beirut be weakened, Cairo, Amman, and Washington were pressured to rapidly respond in kind. Still, some states may not be convinced of Damascus’ sincerity in permitting an “Arab influence” across its border. Recent weeks have seen the eruption of a serious diplomatic row between the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council and Lebanon, which included Riyadh, Manama, Abu Dhabi, and Kuwait City recalling their ambassadors in Beirut. Saudi Arabia, speaking on behalf of its allies, justified the move by calling out Hezbollah’s continued dominance in Lebanon, as well as its role in smuggling Captagon into the Gulf.

While the Lebanese drug trade has generated significant diplomatic crises for politicians in Beirut, al-Assad has been able to harness Syrian Captagon to stimulate direct regional engagement. Unlike Hezbollah in Lebanon, al-Assad runs a narcotics cartel alongside a sovereign state apparatus. Thus, regional players have incentive to deal productively, rather than punitively, with Damascus. As Limassol’s Syria-focused Center for Operational Analysis and Research reports, only al-Assad has the power to end the Syrian drug trade. But, in order take action, he would need substantial financial incentives: Captagon currently brings in over 80% of Syria’s foreign exchange. Despite intense skepticism over the feasibility of drug enforcement cooperation with al-Assad, there is, in fact, a precedent for such cooperation, set by his father in the early 1990s. In a display of pragmatic flexibility characteristic of Ba’athist Syria, then-President Hafez al-Assad cracked down on regime-controlled drug production in return for removal from Washington’s narco-state list, receipt of substantial petro-investment, and access to U.S. imports. While only Jordan has openly stated its intention to work with the Syrian regime to counter drug-trafficking, left with few other alternatives, states across the region will likely look to the 1990s model as a way to alleviate intensifying drug problems.

The 37th Arab League Summit: A Watershed Moment for the Syrian Thaw

While Egypt, the UAE, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain are some of the most important actors to have embarked on normalization with Damascus, it is important to keep in mind the positions of the other Arab states. If Syria is to return to the Arab League and symbolically crown its legitimacy, all member states must reach consensus (though even without consensus, Damascus may be able to sit as an observer state). Lebanon and Iraq, similarly subject to Tehran’s influence, have long been staunch supporters of Damascus, sharing mutual economic and security interests. Lebanon voted against Syria’s expulsion in 2011, while Iraq abstained. Algeria, host of the summit, has openly backed Damascus’ return; President Abdelmajid Tebboune indicated that Syria is “supposed to be present.” Algiers is reportedly interested in reasserting itself as a leading diplomatic force in the Arab world, and shares with Damascus mutually-reinforcing, rhetorical commitments to pan-Arabism, socialism, and anti-imperialism. Comoros, Djibouti, Libya, Mauritania, Palestine, Somalia, and Yemen–weak actors in their current states–are unlikely to oppose the wishes of the Arab League’s dominant players.

The more influential Morocco and Tunisia, which once sought to distance themselves from the al-Assad regime and its brutal response to Arab Spring protests, have both indicated their tentative support of Syria’s readmission since 2019. Kuwait and Oman–neutral Gulf players usually hesitant to take partisan positions on regional issues–are also ready to welcome Damascus back, so long as all members of the Arab League agree. As such, Qatar is set to play kingmaker in Algiers. So far, Doha has categorically objected to bilateral normalization with Syria, as well as a preliminary agreement to invite Syria to the upcoming summit, insisting that Damascus first engage in meaningful dialogue with the Syrian opposition and concrete political reform. Yet, it remains to be seen whether Qatar attaches the same importance to the Syria file as it does to relations with Iran, a close ally pushing for Syria’s regional reintegration, or its Gulf neighbors, with whom it just reconciled following four years of diplomatic hostility and isolation.

According to Dr. Ezzedine Choukri Fishere, Damascus’ return to the Arab League will simply depend on Doha’s priorities, as well as those of its interlocutors: “it is not a structural issue, but simply a deal among many deals. What will Qatar prioritize? That will be decided by one or two people [Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani and his entourage].” Dr. Joshua Landis believes reintegration is only a matter of time, especially given Syria’s geographic centrality to the entire region. In his words, “one can put [normalization] off for some period, but not forever.” He adds that “[although] the U.S. could prevent Syria from being brought in from the cold, it would be expensive, and Syria is not that important to the Biden foreign policy team.” As such, whether Syria makes an appearance in Algiers or not, it appears likely that the Syrian Thaw will stay the course.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News