Putin has been seen as rational and realist in his foreign and security policy, calculating and often opportunistic. His decision to mount a full-scale military assault on Ukraine, however, highlights a shift by Russia’s president to embrace ethno-nationalist motivations, driven by a sense of a historic mission to rectify perceived injustices and to regather lost Russian lands and Russian communities. This suggests that Putin’s agenda is wider than conquering Ukraine.

Opening his national address on Ukraine on 21 February, President Vladimir Putin addressed the citizens of Russia, but he soon extended the reach of his comments to ‘our compatriots’ in Ukraine, reflecting his belief that the borders of the Russian nation stretch far beyond the borders of the Russian state. In the build-up to the Russian military assault on Ukraine, Russia’s leadership sought to cultivate a picture of ethnic Russians, Russian speakers and Russian citizens facing genocidal policies in Ukraine as a result of the rise of Ukrainian neo-Nazis and nationalists to power following the collapse of the Yanukovych regime in 2014.

The idea that Russia has a particular responsibility for the Russian communities outside Russia became a core part of the identity of Moscow’s foreign policy elite in the early 1990s and has been a key driver in the evolution of Russia’s approach to its neighbourhood. While there is clearly an instrumental calculation in the contemporary use of the Russian diaspora issue by Putin, since his return as Russia’s president in 2012 the ethno-nationalist dimension of Russia’s regional policies has acquired a greater significance, notably focused on Ukraine. Increasingly for Putin, regathering the former Russian imperial lands and peoples has moved from being an instrument of foreign policy influence to a goal. This raises concerns about Russia’s future policies, not just in Ukraine and Belarus but for other countries in the region.

The Russians Beyond Russia Debate in Moscow’s Foreign Policy

In the early 1990s, a fierce debate emerged in Russia about its future foreign and security policy, notably in regard to its neighbouring states. While President Boris Yeltsin and his Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev favoured a focus on building ties with the transatlantic community, various nationalist and statist figures argued for a focus on the ‘near abroad’, especially as conflicts developed in Central Asia, the South Caucasus and Eastern Europe, as well as Russia’s North Caucasus region.

Within this political struggle, the fate of the 25 million ethnic Russians residing outside Russia in the newly independent states following the collapse of the Soviet Union – notably in the Baltic states, Ukraine and Kazakhstan – emerged as a key issue. Critics of Yeltsin’s foreign policy argued that Russia had a unique responsibility to these communities, and that this required Moscow to take a leading role in the former Soviet Union. By the mid-1990s, the transatlantic grouping was defeated – with Kozyrev resigning in 1996 – and acceptance of a legitimate interest in Russian communities beyond Russia became a foundational principle of post-Soviet Russian foreign and security policy.

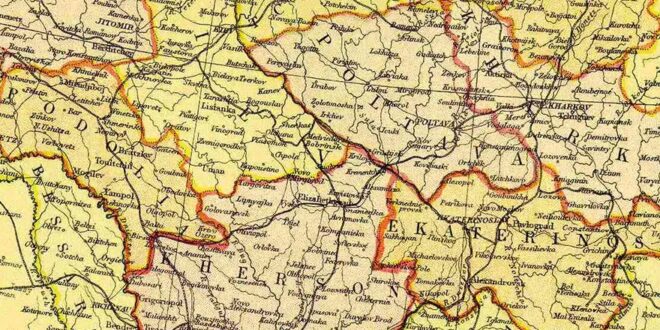

While the idea of Russian responsibility for the Russian diaspora was agreed, operationalising the concept proved challenging as there was no clarity about who exactly was part of the Russian diaspora, with ‘Russianness’ defined differently in different contexts. The legacy of the expansion of the Russian Empire and the development of Soviet nationalities policies was a complex mosaic of different communities scattered across Eurasia with historical ties to Russia. Thus, in Ukraine, language emerged as a central dividing line, while in Kazakhstan Ukrainians, Poles, Cossacks and even Koreans were grouped together as Russians. Faced with the difficulties of establishing a clear basis for action, Russia adopted instead the all-encompassing term of ‘compatriots’ to cover these large and diverse communities.

The Rise of the Russian Nation in Putin’s Foreign Policy

The shift to view a broad range of ethnolinguistic communities outside Russia as a Russian state interest saw Russia taking a strong stand on the issue in the late 1990s and early 2000s, notably with respect to the rights of Russians in Latvia and Estonia as the Baltic states moved towards EU and NATO membership. Russia also sought to challenge state language policies in the region as they moved to displace the role of Russian in favour of titular languages.

For Putin, the historic role of Russia in Eurasia and in regathering the Russian communities has been amplified since 2014, interweaving nationalist ideas with a neo-imperial longingWhile Russia adopted a strong rhetorical line on the alleged violations of states against Russian communities, Russia had little capacity to engage with, influence or support these groups. The Russian authorities thus sought to develop their links to the Russian diaspora, for example by extending dual citizenship to Russians abroad, and through the creation of organisations to mobilise Russians in neighbouring states, such as the Congress of Compatriots Living Abroad. Russia also sought to advance a soft power and cultural influence project that overlapped with the expanded definition of the Russian nation through the idea of the Russian World. These efforts were intended as a means to exert influence and to give substance to the claim of Russia having a special regional role on the basis of its responsibility to the diaspora.

Faced with the challenges and complexity of engaging with such diverse communities, in the 2000s Russia adopted a largely pragmatic and instrumental approach to the issue. Russia’s growing tensions with its neighbours, however, increasingly brought the Russian diaspora issue to the forefront of Russian regional security policies. During the Russia–Georgia war of 2008, for example, the Russian government claimed that its military actions were justified by the need to protect Russians and Russian citizens in South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

With Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, it was clear that he had adopted a different and more strident line on Russia’s foreign and security policy, notably towards the transatlantic community. Claims about Russia’s role in the historical lands of the Russian Empire were increasing interwoven with a narrative about resisting encroachment by NATO and the EU and restoring a dominant role for Russia in the region.

Putin’s 2014 decision to annex Crimea and initiate a proxy conflict in Donbas marked a turning point. The principal motivation articulated by Putin for the intervention was a mixture of claims of responding to violence against Russians in Ukraine, opposition to the rise of a Ukrainian national movement, and emotive appeals about regaining historical Russian territory. Putin’s speech following the formal joining of Crimea to Russia encapsulated the fusion of these various ideas, identifying Crimea as an ‘indivisible’ part of Russia through ethnolinguistic and imperial ties.

Putin, the Russian Nation, and the Russian Empire

While there was widespread popular support in Russia for the annexation of Crimea and a surge in nationalist sentiment, in subsequent years the public’s enthusiasm for foreign adventures declined significantly, and it seemed that ideas of Moscow pursuing an expansionist foreign policy had run their course. For Putin, however, the historic role of Russia in Eurasia and in regathering the Russian communities has only been amplified, pointing to an interweaving of nationalist ideas with a neo-imperial longing.

In the spring of 2021, Putin released a long essay on Ukraine that not only asserted the special regional role of Russia but aimed to undermine the whole idea of a Ukrainian nation and Ukrainian statehood. These are themes that have returned in Putin’s recent televised speeches announcing the recognition of the Russian-backed proxy regions in Ukraine and the onset of Russia’s invasion, as well as denouncing Ukraine’s leadership.

Putin has become convinced that his historic role is not just to overcome the end of the Soviet Union, but to undo the Bolshevik nationalities policies that laid the foundations for the contemporary state system of EurasiaThe build-up to the war with Ukraine was also accompanied by Putin claiming in December 2021 that something approaching genocide was happening in Ukraine against Russian communities. Immediately before Russia’s military operation, he went further, indicating that what is ‘What is happening in the Donbas today is genocide’. Ahead of a UN Security Council meeting to discuss the crisis, Russian diplomats circulated a dossier accusing Ukraine of ‘exterminating the civilian population’ in the breakaway regions of Donbas.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 also represented the collapse of the Russian Empire, which had been swallowed by the Soviet Union and was subsequently reconfigured by Bolshevik leaders through their nationalities policies. Putin has become convinced that his historic role is not just to overcome the end of the Soviet Union, which he famously described in 2005 as the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the 20th century, but to undo the Bolshevik nationalities policies that laid the foundations for the contemporary state system of Eurasia.

At the core of this project is Moscow’s role as a guarantor and protector of the Russian nation, although the definition of the Russia nation is broad and consists of overlapping ideas of ethnic, linguistic and cultural Russianness. Such a flexible concept allows for a meshing of Russian state interests with claims to be acting to protect a diversity of ethnic and linguistic communities outside Russia. It also negates the idea of other legitimate national communities that could underpin states in the region. While there may not be a groundswell in Russia to support such an agenda, these ideas build upon thinking that is widely supported among the Russian political elite.

The agenda and ideas that Putin has set out to justify military action against Ukraine thus represent the culmination of a strand of thinking about Russia as a foreign and security policy actor that makes regathering Russian ethno-national communities and former Russian imperial lands the ordering principle for the territories of Eurasia. The immediate aim of Putin’s policies is Ukraine, but also Belarus, which is being incorporated into a Russian sphere of influence through the war. Putin’s agenda is, however, unlikely to stop here. Moldova, the South Caucasus and the states of Central Asia – notably Kazakhstan, where Russian nationalists have claimed the northern regions, reflecting the significant Russian community there – will all be vulnerable to Russian expansion if the war in Ukraine succeeds.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News