Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was met with unprecedented economic sanctions by the United States and its allies in order to cripple Russia’s capacity to wage war. Never before in post–World War II history has an economy of Russia’s size been reprimanded with such force. Moreover, the sanctions could remain in place after the war ends and reach other major economies too, in particular China. In this case, current sanctions could be the harbinger of a longer-term economic war with dire consequences for global productivity and welfare.

Sweeping Sanctions Invite Countersanctions

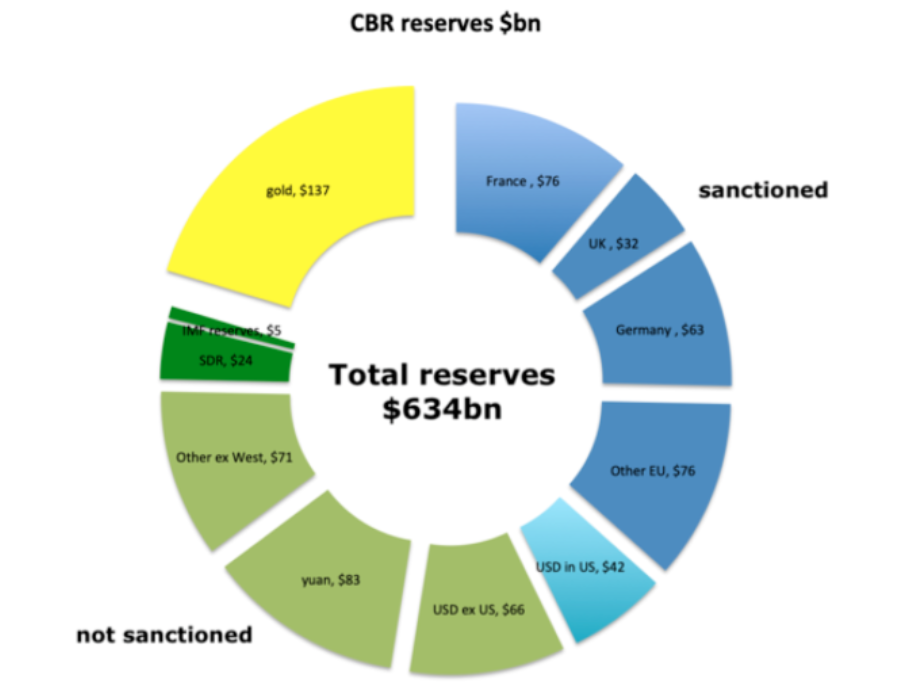

The round of sanctions imposed on Russia following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 were limited to travel bans, freezing of the assets of certain Russian officials, and a prohibition of credit and technology transfers to Russian state oil companies and banks. After the invasion of Ukraine, in addition to the freezing of the financial assets of Russian oligarchs close to the regime, sanctions were escalated to the technology, steel, energy, and financial sectors. The US stopped imports of Russian oil and gas, and the European Union moved to drastically reduce its dependence on Russian energy too. Several Russian banks were cut off from the SWIFT system, and, most important, the reserve assets of the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) were frozen, together with its sovereign wealth fund. Experts estimate that Russia has lost access to about 40 to 60 percent of the CBR’s international reserves, valued at $640 billion, which is a huge financial blow. In addition, the US banned the trading of the CBR’s gold reserves, estimated at $136 billion, or another 20 percent of its total foreign reserves (graph 1). Finally, over five hundred foreign companies have announced that they are voluntarily suspending operations or leaving the Russian market altogether.

Graph 1: Central Bank of Russia reserves

Russia likened the sanctions to an “act of war” and retaliated by prohibiting exports of certain commodities and raw materials and demanding payment for its energy exports in rubles, to undercut some of the West’s financial sanctions. After the reciprocal closure of air spaces, Russia also allowed Russian airlines to reregister and fly domestically about five hundred planes leased from abroad, worth about $10 billion, which is tantamount to their seizure. Moreover, Russia threatened to nationalize the assets of multinationals that suspend their operations in the country. But the German government moved first, taking control of the Gazprom subsidiary in the country to ensure the security of the German energy supply.

Russia hosts a sizeable stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) of about $500 billion, the majority, about 75 percent, of which originates in the EU (in particular in Cyprus) and around 5 percent in the US. If the US and its allies move to confiscate Russia’s forex reserves, the latter could seize the Russian assets of Western companies, which are worth roughly the same amount. Russia owns a smaller amount of FDI abroad of about $390 billion, which is likely more evenly spread between Western and emerging economies. Russia could also stop servicing its external debt if some of its external assets get confiscated, in particular now that the US Treasury has stopped Russia from making bond payments from its frozen reserves. Russia’s external debt of about $480 billion, of which close to $100 billion is owed by the government, is also large. These figures illustrate well that financial stakes would be very high in the case of tit-for-tat asset seizures and contract defaults, not mentioning the severe consequences of foregone future trade and business.

Sanctions in Breach of Property Rights

The type and size of financial sanctions applied so far go beyond an ordinary trade war. Boycotting foreign products, markets and business operations abroad can be economically painful, but are legitimate actions that do not encroach upon private property rights. On the other hand, government direct or indirect prohibition of foreign trade and business operations are not only invasive of private property rights, but also economically more damaging, given their larger scale. Seizure and outright confiscation of foreign assets appear even more harmful in terms of property rights if they are not the outcome of legitimate court decisions or international contracts and treaties, such as UN resolutions. Only in such cases would they comply with both the letter and spirit of the US constitution.

The parties hit hard by sanctions have already complained about getting robbed. And regardless of who stands to lose more from mutual expropriations, these can easily lead to further escalation of sanctions and a full-fledged economic war eventually. Today’s breach of contracts and property rights will most likely dent business confidence, trade, and investment in the future. Countries like China, Saudi Arabia, and India are already considering moving away from the US dollar in international transactions, either to avoid current sanctions or prepare for potential future ones.

Mere Sanctions or a Harbinger of Economic War?

So far, the impact of sanctions has not undermined Russia’s will to continue the war. Despite the drop in hydrocarbon exports to the Western economies, Russia’s current account surplus increased to $39 billion in January–February of this year from $ 15 billion a year before, on account of surging energy prices and compression of imports. The ruble has also recovered nearly all the losses incurred against the US dollar when sanctions were announced. The pressure on external accounts and the economy will mount as the West cuts its energy dependency on Russia, but the latter’s energy and commodities exports will most likely find other outlets in emerging economies. Economic interdependencies cannot be undone overnight, and markets will redirect international trade flows to reduce the economic cost of the sanctions.

President Joe Biden no longer claims that economic sanctions will work in the short term but still wants to keep them in place for much longer. It may well be that seized Russian assets are kept to cover for future war reparations in favor of Ukraine or that sanctions are applied for as long as Putin remains in power. Other US allies, such as the UK, are also in no hurry to lift sanctions as soon as the war stops. Moreover, the sanctions are not as effective as hoped for, because Russia continues trading with other emerging economies, which together make up about 40 percent of the world GDP (gross domestic product) nowadays. The US and its allies have put pressure on China, India, and others who have not condemned Russia or applied economic sanctions, also threatening them with secondary sanctions, but most have stood their ground so far. Even US partners in the Middle East have ignored Biden’s calls to pump up more oil in order to tame petrol prices.

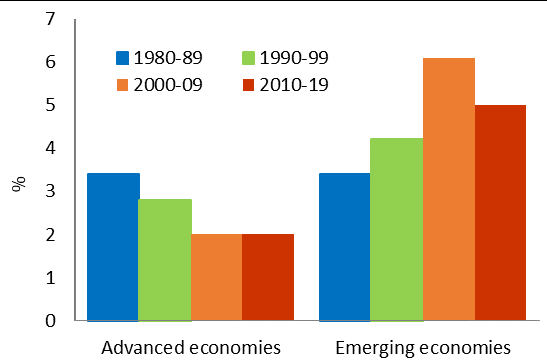

It cannot be ruled out that the economic war against Russia will eventually spread to China and others via secondary sanctions and growing political animosity. Before Russia’s invasion, the US was already in a trade and technology war against China. EU countries have also taken a tougher stance against China by shelving an investment agreement and screening more carefully technology transfers. A decoupling of the world economy into two opposing blocs of “democratic” and “autocratic” regimes does not seem a farfetched prospect anymore. Certain Western leaders may even welcome it as the only “solution” to counter the mounting economic competition from fast-growing emerging economies (graph 2).

Graph 2: Real GDP growth

Deglobalization Would Have Calamitous Economic Consequences

In the short run, the war in Ukraine is likely to have a severe negative impact on the global economy. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) expects that the economies of Ukraine and Russia will shrink by 20 percent and 10 percent, respectively, in 2022 and that real GDP growth will decelerate by 2.5 percentage points on average in the regions where it operates—i.e., eastern, central, and southeastern Europe; Central Asia; Turkey; and the southern and eastern Mediterranean. The World Bank has also warned that the war in Ukraine will push millions of people into poverty and dozens of poor countries will get into a debt crisis.

But the longer-term consequences of the sanctions are likely to be much more severe, in particular if they spill into a wider economic war. Sanctions and their harm on business confidence are expected to greatly reduce Russia’s trade and investment with the West for decades. The war has also brought into question again the reliability of global supply chains and reinforced previous calls for developing strategic industries domestically and strengthening economic sovereignty. If the globalization process of the last three decades is over and current sanctions escalate into a global economic war, the loss of productivity from dismantling the international division of labor could be substantial. A recent study found that a 1.0 percent increase in economic globalization raised productivity by 0.5 percent in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in the long run. Deglobalization would shave that off both productivity and real GDP growth rates.

Hefty sanctions also usefully serve the less conspicuous interests of governments, which also makes them hard to lift. The embargo on Russian energy, which sent the prices of oil and gas through the roof, is helping accelerate the transition from fossil energy, but raises the social costs of implementing Green Deal plans rapidly. The push for rearmament increases public spending and taxation, usually to the benefit of the military-industrial complex. In addition to the unfortunate loss of human lives, tremendous suffering, and economic destruction, wars go hand in hand with a tightening of government control over civil liberties and dilution of human rights.

Murray N. Rothbard recognized this all too well when he exposed his libertarian position against all wars waged by the state. Despite any good intentions, it is almost inevitable that any interstate war would involve aggression toward private individuals and their property on each side of the conflict, either through military action, conscription, or taxation. Therefore, Rothbard calls for the swift ending of any war and warns that “domestic tyranny … is the inevitable accompaniment of inter-State war, a tyranny that usually lingers long after the war is over.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News