Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine is also a war on global food security. In February 2022, Russia blockaded all of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, through which all its bulk exports were being shipped. The ports remain closed, with no opening in sight. David Beasley, the executive director of the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), recently warned, “When a country like Ukraine that grows enough food for 400 million people is out of the market, it creates market volatility, which we are now seeing.”

Beasley made clear how grave the crisis is as Russian forces preventing Ukraine’s exports from getting to market threaten to plunge vulnerable populations into peril. “Truly, failure to open those ports in Odesa region will be a declaration of war on global food security,” said Beasley. “And it will result in famine and destabilization and mass migration around the world.”

In recent years, Ukraine’s export revenues from both goods and services have surged, thanks to booming agricultural production and rising commodity prices. They soared from $124 billion in 2020 to a record of $166 billion in 2021, while Ukraine’s gross domestic product (GDP) was $200 billion. Meanwhile, the share of agriculture in Ukraine’s export revenues from goods increased from 26 percent in 2012 to 45 percent in 2020.

Russia has further aggravated this food crisis by bombing and burning grain storage in the south and east of Ukraine, by stealing hundreds of thousands of tons of grain, and by exporting it on its own ships, primarily to its ally Syria.

Russia’s war on Ukraine’s grain exports should not be allowed to continue. The collective West needs to open Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, primarily the major ports in Odesa, to mitigate the ongoing crisis in countries suffering from food insecurity, as well as enabling Ukraine to sell the twenty-eight million tons of grain it has in storage.

Ukraine is a global granary

Before communism, Ukraine was the granary of the world; since the privatization of agricultural land in 2000, it has become so again. Its grain production has skyrocketed, and Ukraine is now focusing on modern grains—corn, wheat, soy, canola, and sunflower oil.

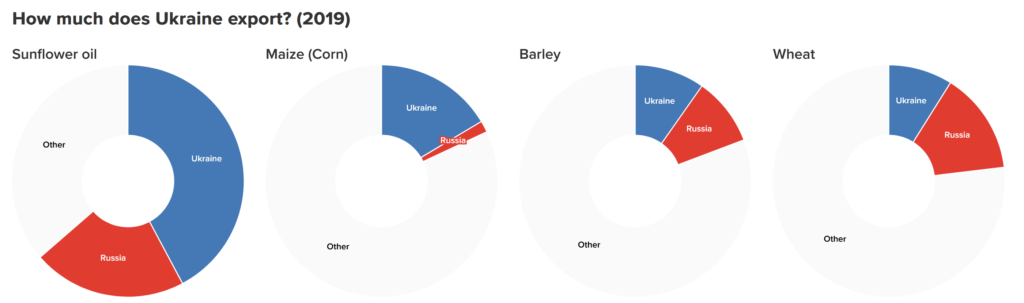

Ukraine is a major producer of many grains. In 2021, it produced some eighty-six million tons of grain. The latest reliable statistics are for 2019 from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. In 2019, Ukraine produced 35.9 million tons of corn. It was the fifth-biggest grower of corn after the United States, China, Brazil, and Argentina, producing 3.1 percent of all corn in the world. Ukraine produced 28.4 million tons of wheat, or 3.7 percent of global production, ranking seventh in the world, after China, India, Russia, the United States, France, and Canada.

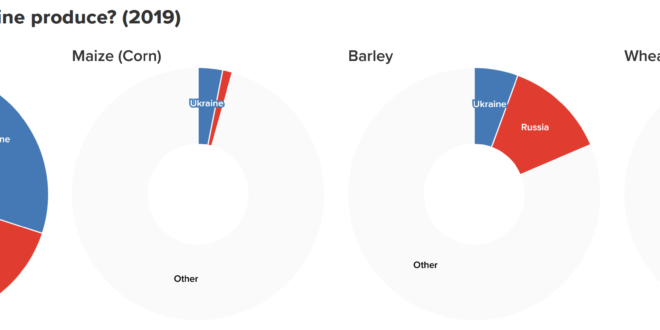

Ukraine’s role as an exporter of grain is much greater, because most of the other major producers are very large countries, such as China, India, the United States, Indonesia, and Brazil, which consume much of their produce themselves. In 2019, 42 percent of all global sunflower-oil exports came from Ukraine, as did 16 percent of all corn exports, 8.9 percent of all wheat exports, and 9.7 percent of all barley exports. Because of Ukraine’s swiftly expanding agriculture, the country’s role as a grain exporter has risen fast.

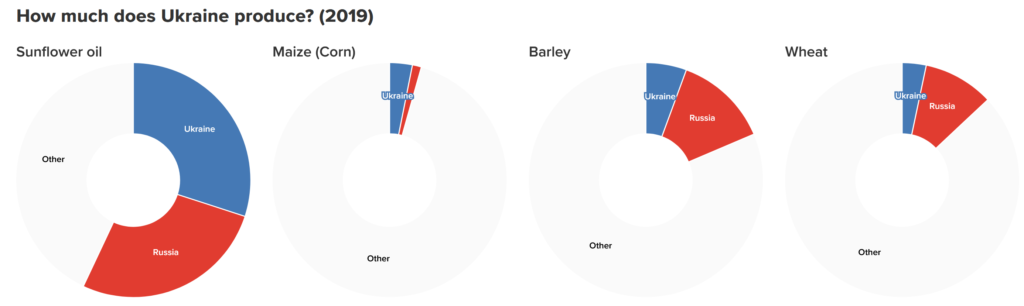

Most attention is being devoted to wheat because it is crucial for economically developing countries’ supplies of bread, a basic staple. With its steadily improving agriculture, Ukraine’s exports have risen in turn. For the year until July 2021, the US Department of Agriculture assessed Ukrainian exports of wheat at 23.5 million tons. These wheat exports were spread to many countries in Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. The main recipients by quantity were Indonesia, Egypt, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Morocco, Turkey, Yemen, Tunisia, Libya, Lebanon, and the Philippines. These countries are most likely to suffer from a new shortfall of wheat.

Corn is the second important grain export. Ukraine has nearly perfect conditions for growing corn, similar to those of the US states of Iowa and Illinois, and corn production has grown exponentially. For the year until July 2021, the US Department of Agriculture assessed Ukrainian exports of corn at thirty-four million tons. The corn exports went in quite different directions from the wheat exports, going to somewhat wealthier countries, because corn is mainly used for animal feed. In recent years, Ukraine’s main market has been China, which bought no less than 8.4 million tons of Ukraine’s corn exports in 2020–2021. Other major purchasers were Spain, the Netherlands, Egypt, and Iran.

Officially, Russia closed vast expanses of the Black and the Azov Seas for civilian maritime traffic, under the pretext of naval exercises, for the period from February 13–19. It had no legal basis for this decision. Thus, Russia closed the access to all Ukraine’s ports from the Black Sea, and the ports have remained shut ever since. Russia has also mined them. Russian naval ships have hit at least ten commercial ships since Russia launched its assault, according to the International Maritime Organization. They sank one Estonian commercial ship. About eighty commercial ships have been caught in the Black Sea or the Sea of Azov for months. The risk to commercial shipping in the area has soared, and the cost of marine insurance in the Black Sea has skyrocketed as a result.

A tight global grain market

In recent years, the global grain market has tightened fast because of production problems in many parts of the world, which are largely connected with climate change. The two big positive exceptions have been Russia and Ukraine. As a result of a tightening global grain market, global prices have risen greatly. By and large, global wheat prices have doubled since early 2021. The Euronext Paris milling price of wheat has risen from about 200 euros per ton in early 2021 to 400 euros a ton at present.

Food is a highly sensitive political issue. As politicians are anxious to keep food prices low, they want to keep scarce domestically produced grains at home, and shortages often provoke export bans. More than twenty countries have already imposed export bans on food, including important grain producers such as India and Indonesia. More countries are likely to follow, further aggravating the global shortage of grains.

As the global grain market grows tighter, many traditional exporters prohibit exports to keep their domestic prices low, to avoid political tensions. But, as they prohibit exports, global grain prices rise further, and the economically weak countries that struggle to afford their vital grain imports suffer the most.

How can Ukraine get its grain to market?

Out of Ukraine’s total grain production of some eighty-six million tons in 2021, about twenty-eight million tons are stuck in Ukrainian ports because of the Russian naval blockade. Ukraine has limited storage available—and, after some time in storage, much of the grain perishes. Moreover, new sowing and other work require financing, and the Ukrainian farmers need to be able to sell their grain in order to acquire financing for the next year’s harvest.

At the Stuttgart Group of Seven (G7) conference from May 12–14, Ukraine’s Minister of Agrarian Policy Mykola Solsky laid out the situation, saying, “Due to the blockade of Ukrainian seaports, 7 million tons of wheat, 14 million tons of corn, 3 million tons of sunflower oil, and 3 million tons of sunflower meal and other crops have not entered the world market.” Usually, Ukraine would export 6–7 million tons a month through its Black Sea ports, but they are blocked, and the Russians offer no sign of easing up.

Ukrainian exports fell by 58 percent and imports by 76 percent from March 2021 to March 2022, which reflects just how devastatingly Russian warfare has hindered much of the production and transportation of goods in Ukraine.

Ukraine has no alternative seaports for its large grain volumes. Rail or truck transportation can take some volumes through Poland or Romania, to the Polish port of Gdansk, the Lithuanian port of Klaipeda, or the Romanian ports on the Danube River or the Black Sea. At present, these alternative routes can only manage about one-tenth of the demand, 400,000–500,000 tons per month, but they can rise to 2 million tons per month, according to Ukrainian agricultural experts interviewed by the author, and the delays are substantial and costly. The delays are caused by both infrastructure bottlenecks and seemingly excessive border controls. The rail transportation is being impeded by Ukraine having broad track gauge (the distance between the two rails on a railway track), matching railways in Russia, Belarus, and the Baltics, which are different from railways in Poland and Romania.

The alternative transportation routes are cumbersome, small, and costly. Usually, the transportation of grain to a Black Sea port costs a Ukrainian grain producer about 10 percent of the price. Once there, one of the big international grain traders buys the grain and takes it over. Currently, the added cost to transport grain to Gdansk or Klaipeda adds about 30 percent. Considering that European grain prices have doubled in a year, that is not prohibitive, but the capacity remains tiny—whatever Ukrainian exports make it to these ports are unlikely to make the difference needed to mitigate the global food crisis.

The only substantial option for the export of grain is through the Ukrainian Black Sea ports, primarily the Pivdenny and Odesa ports in the Odesa region. There is no viable alternative.

Accusations of Russian destruction and plunder

The Kremlin has by no means ignored the global food crisis. To the contrary, it has decided to aggravate and exploit it. Ample Ukrainian sources report that the Russian military has intentionally bombed and burnt Ukrainian grain elevators, fertilizer stores, farming areas, and infrastructure.

Russians have stolen grain on an industrial scale. Ukraine’s Deputy Agriculture Minister Taras Vysotskiy stated in early May that Russians had exported 441,000 tons of grain from the four occupied regions of Zaporizhia, Kherson, Donetsk, and Luhansk. They transported the stolen grain on trucks to Novorossiisk, the main Russian port on the Black Sea, or Sevastopol, the top Crimean port. Then, they ship the grain through the Bosporus to Mediterranean ports. Ports in Cyprus and Lebanon have reportedly turned down delivery of stolen grain, while Russia’s ally Syria accepts it. However, Vysotskiy states that only 1.5 million tons of grain was stored on newly occupied territory.

Putin has a long history of personal involvement in major graft operations, and is reportedly micromanaging elements of the war on Ukraine. Businessman and human-rights leader Bill Browder showed how such business is done in his investigation of the Sergei Magnitsky affair. Of the $230 million stolen from the Russian tax office, the Panama Papers showed that $800,000 had gone to President Putin himself, and Putin fought tooth and nail to defend the theft from his own government. Given Putin’s history and the big business of stealing and selling Ukraine’s grain, it is likely that these new operations are being organized at the highest level.

Similarly, since 2014, Russian government-supported business has exported coal from illegally confiscated coal mines in occupied Donbas to Russia, Belarus, Poland, and Turkey, leading to legal cases in Poland and Turkey. This is part of the Putin government’s close cooperation with organized crime, which has been deeply detailed in recent books by Karen Dawisha, Bill Browder, Catherine Belton, and this author.

How the Russian blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea Ports can be ended

Since early February, Russia has blocked all of Ukraine’s seaports without any legal excuse or recourse. In the first month of the war alone, the Russian navy attacked at least eight civilian commercial freight ships, and has caused one Estonian freight ship to sink, likely from a mine. These disturbing events have received relatively little international attention. Russia has mined all the Ukrainian ports with hundreds of mines. The three NATO countries around the Black Sea—Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey—have all reported that loose mines have reached their territorial waters.

For too long, the undeclared Russian blockade of all Ukrainian Black Sea ports has attracted little international attention in spite of its many negative effects and the absence of a legal case. Since half of Ukraine’s exports are grain, the blockade deprived Ukraine of roughly half its exports earnings, adding a serious economic dimension to the Kremlin’s full-scale war on Ukraine. Combined with the potential effect of starving approximately forty-seven million people, the seriousness of Russia’s blockade cannot be understated.

At long last, the West appears to be waking up to this disaster, and has started to consider doing something. From May 12–14, the foreign ministers of the G7 countries warned that “Russia’s war of aggression has generated one of the most severe food and energy crises in recent history which now threatens those most vulnerable across the globe…We are determined to accelerate a coordinated multilateral response to preserve global food security and stand by our most vulnerable partners in this respect.”

But how can this be done? Moscow correctly assesses that the blockade is a major blow to the Ukrainian economy and a potent tool in its war to cripple Ukraine—so how can the US and its allies make the Kremlin stand down?

The first step is to rally international support to lift the blockade. Moscow has taken comfort from the fact that non-aligned nations have not come out strongly against its aggression in Ukraine. But some of the most impacted victims of the Kremlin-induced food shortage are prominent nations like Egypt and Indonesia. The G-7 should begin a massive public diplomacy campaign to ensure that key nations in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and South Asia understand the origins of the food shortage and the obvious solution—to open shipping from Odesa, at a minimum for vital food supplies. The aim would be to bring this issue to the UN General Assembly for a resolution calling for an end to the naval blockade in the Black Sea, at least on food. This effort will force Moscow to pay a greater political price for the blockade.

At the same time, the US should explore creating a coalition of willing states to establish a humanitarian maritime channel to Odesa to escort food products out of dangerous waters in the Black Sea. This maritime channel could also be used to deliver crucial humanitarian aid to Ukraine. The group should include NATO allies and especially Turkey, as well as interested partners and key non-aligned states that import grain from Ukraine and that have a strong navy.

Turkey is essential to include to ensure that there is no problem with the 1936 Montreux Convention, which governs the passage of vessels through the Bosporus. Given its strong navy and history in successfully standing up to Russian military brinksmanship, Turkey would be valuable in a key role for any international coalition. Egypt is a major grain-importing country impacted by this crisis with a navy that could assist with demining.

While this approach contains risk of a confrontation with Russia, it is worth noting that the US navy delivered humanitarian aid to Georgia during the 2008 war while avoiding any serious escalation with Moscow. Creating a large international task force would raise the risks to Moscow of using force to deny access to and from Odesa.

This proposal is already gaining traction. On May 22, Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis argued that “The countries who consider the looming global food crisis a serious challenge…should guarantee a safe passage of ships from Odesa across the Black Sea to the Bosporus.” Landsbergis went on to affirm that guaranteeing food-supplies is not an escalation, and that urgent action is required to avert a deeper crisis.

In parallel, the West needs to reinforce Ukraine’s naval defense, notably with the delivery of potent anti-ship missiles and mine-sweeping facilities. Denmark is already moving in this direction, pledging the delivery of Harpoon anti-ship missile systems to Ukraine. These systems will bolster Ukraine’s ability to defend against Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, but could take months to train on and integrate into the country’s coastal defense system. Further deliveries of these systems should take place immediately.

Finally, the US, the EU, and other partners from around the world should consider possible economic measures to force Moscow to end the blockade. This could include an embargo on all Kremlin shipping. It might also include sanctions on all insurers for Russian shipping.

This broad range approach holds open the door to ending the blockade, but certainly increases the price to Moscow of continuing it and will add new nations to the list of those who oppose Putin’s war on Ukraine.

Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s war of aggression has seen remarkable success. But, with the war likely to continue for the foreseeable future, the deeply destabilizing impact on the global economy appears set to continue as well, with tens of millions of people in the Global South being plunged into mass starvation. To reduce the risk of further mass hunger and the ensuing political destabilization, global powers must make it a priority to urgently open Ukraine’s ports for shipping. The operations required to fulfill this mission have successful precedent and can be accomplished without a serious escalation in this conflict.

Russia’s war on Ukraine has sparked sea changes in global politics on a historic scale. As the West grapples with how to move forward, addressing Russia’s culpability in exploiting a global food crisis—and mitigating the damage—is essential.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News