Turkey’s move to pressure Sweden and Finland into extraditing alleged “terrorists” they harbour is a method Ankara used for several years against countries in the Western Balkans, including EU candidate countries, under the idle gaze of Brussels.

While Turkey wields investment and aid as a sword of Damocles over the heads of poorer, less powerful countries, when it comes to the Nordic duo, it is their NATO application filed in May that hangs in the balance.

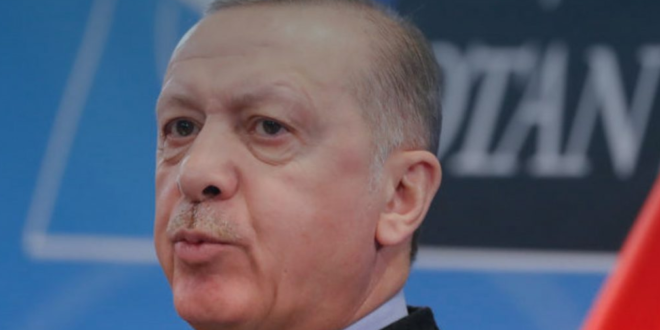

Meanwhile, the similarities between Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, particularly in terms of “crude blackmail tactics” are being noted, as is the need to protect EU borders from revisionist and violent threats from whichever neighbour.

After Sweden and Finland applied to join NATO, Turkey refused to agree, citing the former’s alleged support of members of the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK). Erdogan said that Sweden joining NATO would make it “a place where representatives of terrorist organisations are concentrated.”

Turkey has demanded resolutions to its complaints, including possible extraditions, before it unblocks the veto. But this is not the first time it has used this rhetoric.

Another group that Turkey considers “terrorists” is followers of self-exiled cleric Fethullah Gulen. Often referred to as Gulenists, or “FETÖ” by Erdogan, they have been subjected to a harsh crackdown in Turkey and beyond.

Following a failed coup d’etat in 2016, Erdogan imprisoned and declared wanted thousands of Gulenists. Thousands more fled the country for the West, and many more worked in networks of Gulen-affiliated schools and universities worldwide.

Meanwhile, Erdogan started pumping money across borders into countries such as Albania, Kosovo and Bosnia.

In Albania, Turkey is one of the most prominent investors in infrastructure and business, but the investment to the tune of billions came with strings attached.

“A precondition to our support and brotherhood,” Erdoğan told Albanian parliament in January 2022, “is your commitment to the fight against FETÖ”, adding that “it is our sincere expectation that more concrete, decisive and rapid steps will be taken,” against them.

In 2020, the Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mevlut Cavusoglu, used similar rhetoric while signing agreements on economic cooperation.

A few months later, a network of schools owned by a Dutch company but allegedly linked to Gulen was raided by police without a court order while children were on the premises.

In 2019, Turkish citizen Harun Celik entered Albania with a fake passport and tried to seek asylum but was deported without having the opportunity to appeal the decision in a move described by the Albanian ombudsman as violating national law and international conventions.

Selami Simsek, who entered the country with Celik, was also set to be deported. He was denied asylum by the Directorate of Asylum and Citizenship on 9 March 2020 and 10 September 2020, but fought his case and won.

The EU and various MEPs condemned the moves and called on the government to ensure compliance with the Geneva Refugee Convention.

Meanwhile, in Kosovo, the national Intelligence Agency unilaterally annulled the residence permits of at least six Turkish citizens, who were then arbitrarily detained and deported.

Subsequently, a parliamentary investigation deemed these acts constituted arbitrary detention, forcible disappearance and illegal transfer to Turkey in violation of local and international law.

In July 2020, United Nations rapporteurs found that the Turkish government had signed a number of “secret agreements” with various states to enable systematic “extraterritorial abductions and the forcible return of Turkish nationals”.

At the time, they reported more than 100 people had been subject to “arbitrary arrests and detention, enforced disappearance, and torture” due to collaboration between the Turkish government and countries such as Albania, Kosovo, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Pakistan, Gabon, Afghanistan, and Cambodia.

Ankara also tried its luck with Athens after eight Turkish officers defected via helicopter just hours after the 2016 coup. The Greek government refused to give in to pressure and welcomed thousands of defectors over the years.

Similar attempts at deportations were made in Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina but were stopped by the courts, while North Macedonia said it had been asked to hand over some 86 alleged Gulenists.

At the same time, Turkey continued investing in the countries it asked to comply with its demands and vociferously backed their EU hopes.

Fast forward to 2022, Turkey is exerting pressure on stronger and richer Sweden and Finland, using their application to NATO as a bargaining chip while war simmers at their borders.

Turkish sources told EURACTIV that the issue may also have to do with Gulenists.

Sweden, in particular, has welcomed many such individuals and its also home to the Nordic Monitor portal that reports on the long arm of Turkish intelligence. One investigation in particular exposed documents showing that Turkish embassies in other countries were being used to spy on critics of Erdogan.

EURACTIV contacted the European Commission to ask whether taking action against Turkey’s behaviour in the Western Balkans could have prevented a repeat that impacts both EU member states and NATO.

They responded that it is up to individual countries to “make sure their citizens are not being mistreated in the way you describe or their territory is not used for such actions.”

The Commission said they are “watching and assessing” Turkey’s behaviour.

The former deputy minister of foreign affairs of Greece, MP and professor of international relations Yannis Valinakis told EURACTIV that “Turkish blackmail” and efforts to extort concessions come as no surprise.

“Every dissident is labelled a terrorist in Ankara and every Kurd ‘must disappear’. The original fellow travelers of the Gulenists have been persecuted by Erdogan in recent years mercilessly,” he said.

He explained that EU hopefuls are succumbing to blackmail through aid.

“At the same time, most in the EU, in the name of Turkey’s supposed strategic importance, have for years been indifferently swallowing any unacceptable behaviour by the Erdogan regime,” he said.

But in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the matter becomes even more serious, as “Erdogan’s crude blackmail tactics are directly affecting Turkey’s Eastern European and Scandinavian friends, perhaps [now] they and the EU will finally recognise how much Erdogan and Putin have in common”, he added.

The Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to questions sent by EURACTIV.

Meanwhile, the Commission has ploughed more than EUR 700 million into the Western Balkans to improve the rule of law in candidate and potential candidate states and committed to pouring an equivalent sum over the next seven years.

A recent report from the European Court of Auditors, however, found that this was “ineffective” and “not successful” in these countries, including those that have been engaged in deporting Turkish citizens without following legal and judicial due process.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News