Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine renewed international experts’ focus on Moscow’s earlier military intervention in Syria, launched in 2015, which often became framed as a “testing ground” for the weapons and tactics it now employs against Ukrainian cities. Certainly, direct military action of the type seen on the Ukrainian battlefield — bombing campaigns, assaults on urban areas, drone surveillance, and artillery support — had also played a key role in stunting and eventually rolling back rebel gains in Syria. But crucially, the Russian forces backing Bashar al-Assad’s embattled regime also understood the importance of state-building efforts: chiefly, rebuilding the broken Syrian security forces into more coherent, effective fighting units.

However, rebuilding the entire Syrian Arab Army (SAA), which stood at more than 220,000 soldiers before the war, or demobilizing the hundreds of pro-Damascus militias that had formed since 2011 would be an impossible task while rebels and ISIS still threatened much of the country. Instead, Russia initially focused on forming two new corps that it could directly command and supply. Unifying the command chain between the air forces, ground forces, artillery, and supply lines would be a massive force-multiplier for the Syrian regime, whose forces had been operating more like disparate armed factions merging in and out of operations rooms, rather than as a single coherent military command. These new Russian-built units used high salaries and the offer of reconciliation to entice militias, draft dodgers, and deserters, who would serve alongside veterans and fresh graduates from the military academies.[1] The structure and intended use of these new forces was meant to mirror that of Russia’s first Syrian proxy, the Tiger Forces, a pro-regime unit originally established in 2013 and commanded by Damascus’ Air Force Intelligence (AFI) that drew on a mélange of AFI personnel, ex-special forces fighters, and local, mostly minority, militias from the countryside around Homs and Hama. Indeed, it was the evolution of the Tiger Forces into a more conventional military force, renamed the 25th Anti-Terrorism Division, in 2019, that triggered the creation of Russia’s most recent proxy — the 16th Storming Brigade.

Russia’s Early Attempts at Rebuilding the Syrian Army

Immediately upon intervening in September 2015, Russian officers and ground forces attached themselves to the infamous Tiger Forces, which had built a name for itself as a key offensive unit for the regime after taking a lead role in breaking the siege of the Aleppo Central Prison in May 2014. On paper, the Tigers were a massive 12,000-man unit, equivalent to an SAA division, though the vast majority of these members were reserve fighters who never saw combat.[3] The core combat force of the Tigers more closely resembled a single brigade, consisting of 2,000 to 4,000 men organized into company- and battalion-sized mobile formations.[4] These units, largely formed around communal ties and commanded by local warlords, could be quickly deployed to priority fronts for either defensive or offensive missions. The geographic heart of the Tiger Forces was in Homs and northwest Hama, enabling the force to split units simultaneously between defensive operations along the Idlib front and offensive operations elsewhere in the country.

Prior to the Russian intervention, the power of the Tiger Forces came from the backing of the AFI, widely considered the most powerful of the country’s four intelligence branches, whose political power ensured the group would frequently receive air support from the overstretched Syrian Air Force, and whose deep pockets ensured enough finances to continually recruit new and veteran fighters. With the Russian intervention, the Tigers obtained additional support from the Russian Air Force and artillery units as well as command support from Russian officers. Russian generals, officers, and special forces soldiers have been pictured in the field alongside all levels of Tiger Forces fighters, from its commander, Suhail al-Hassan, to low-ranking field commanders, indicating an intimate integration of Russian assets alongside their chosen partner force.[5]

Russia’s first experiment in replicating this model came a month after the start of their intervention, when they announced the formation of the 4th Storming Corps.[6] The name of the new unit implies it was intended to be used widely in offensive operations across the country. But aside from participating in the 2016 assault in northern Latakia, the unit has remained on defensive duty in a limited area in Latakia and northwest Hama.[7] Heavy reliance on volunteers, poor performance in the 2016 offensive, and recruitment woes made for a disappointing result.

With the 4th Corps project failing to meet Russia’s hopes, and with the crucial battle for Aleppo city drawing more and more regime forces over the summer of 2016, the Russian military began building another military formation, meant to address many of the problems encountered with the 4th Corps. The new 5th Assault Corps was formally announced in November 2016.[8] It is funded, trained, and commanded by the Russians, as evidenced by the death of Russian Lt. Gen. Valery Asapov on Sept. 23, 2017, who was publicly named as the commander of the corps at the time of his death.[9]

The 5th Corps occupies a middle ground of sorts between historically defensive Syrian units and offensive ones. The corps has had a questionable deployment record, with significant claims of mistreatment and a lack of support from partnered Russian units, particularly during the summer 2017 campaign in central Syria.[10] According to analyst Aymenn Tamimi, at its inception, the corps was intended to draw upon the as-yet-untapped manpower reservoir of state employees (who are exempt from mandatory service) and individuals who had already completed their military service.[11] The hope was that by offering competitive salaries on top of the soldier’s civilian salary, a new pool of recruits would be enticed to join the SAA; while at the same time, these new units would be bolstered by more experienced veterans.[12] However, the corps has since become a prominent destination for reconciled rebel factions, particularly from southern Syria.

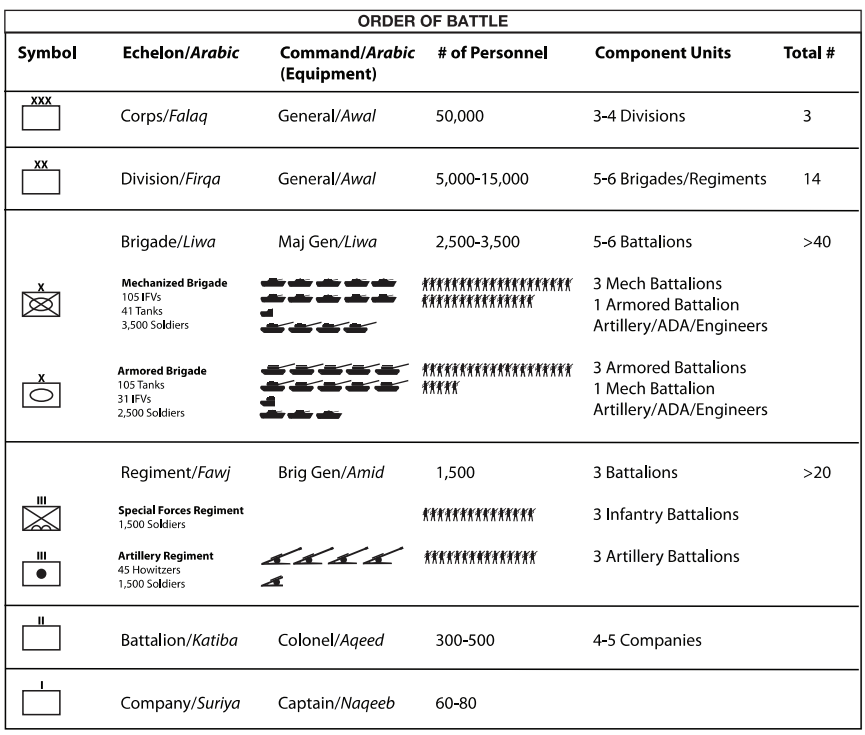

Conflicting reports about the 5th Corps’ effectiveness can be partially explained by the way the unit is structured and supported. The 5th Corps is formed around eight brigades — theoretically consisting of around 2,500 to 3,500 soldiers each — and recruitment, training, support, and deployment appear to largely occur at the brigade level. As noted in the 2013 ISW report referenced above, a standard SAA corps is made up of three to four division, each consisting of five to six brigades. While the 4th Corps is built around this classic structure, the Russians intentionally left divisions out of the 5th Corps. This new system allowed Russia to centralize the command chain of the 5th Corps so that each brigade commander reports directly to the head of the 5th Corps, rather than diluting power with another layer of commanders at the division level. The result is a much smaller-than-standard corps built around units that can be more easily commanded, resembling something like a collection of eight Tiger Forces.

The size and structure of the 5th Corps allowed Russia to extend its reach across the country, simultaneously deploying brigades to nearly every active front. But it also proved impossible for Moscow, or Damascus, to support all eight brigades at once. Variance in combat experience and effectiveness of the 5th Corps often correlated to which specific brigade was involved. For example, the 1st Storming Brigade has a close relationship with the Russian military, sharing the same bases as the Russians in northwest Hama and receiving regular artillery training from Russian officers.[13] The 2nd and 3rd brigades are likewise based in northern Hama and have fought extensively in offensives there and in southern Idlib. Conversely, the 4th and 7th brigades are significantly weaker than the rest of the 5th Corps, drawing more heavily from reconciled Syrians and arrested petty criminals.[14] Both units are the only brigades not headquartered in western Syria — where the bulk of the Russian command is — with the 4th stationed in east Homs and the 7th Brigade positioned in Deir ez-Zor.

The second major transformation came in August 2019, as part of the SAA and Russia’s attempts to move the Tiger Forces out of the control of the AFI and integrate them directly under the SAA high command. Previous efforts in early 2019 to split off the Homs-based Tiger militias had failed, in large part due to a lack of incentives. However, in July of that year, Maj. Gen. Jamil Hassan, the long-standing director the AFI who had overseen the creation of the Tiger Forces, retired. A month later, Assad turned on his cousin Rami Makhlouf, stripping him of most of his companies and money.[15] Makhlouf had been a key financer of the Tiger Forces, and his arrest left the militia exposed and weakened. In what was most likely a coordinated effort, the SAA high command immediately forced the Tigers out of the AFI’s sphere of influence and brought them under the direct control of the new minister of defense, Ali Ayoub. On Aug. 28, Tiger Forces-affiliated social media erupted with posts stating variations of “By order and instruction of President Bashar al-Assad, commander-in-chief of the Army and Armed Forces, [we announce] the creation of the 25th Special Tasks Division (Counter-Terrorism), led by Brigadier General Suhail Hassan.”

With this change in patronage, the Russians and the SAA began restructuring the Tiger Forces, expanding the group from a highly mobile brigade to a more conventional division. The 25th Division consists of Regiments 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, each commanded by either an SAA officer or an AFI officer from the original Tiger Forces. Either way, regimental commanders come from more traditional military backgrounds and have actual ranks, a stark departure from the heavily militia nature of the Tiger Forces’ previous incarnation. The original Tiger Forces groups have now been somewhat organized into numerical companies and battalions within each of these regiments.[16]

Since becoming the 25th Division, the new unit has increased its cooperation with the 5th Corps, and Russian officers directly oversee training at the new 25th Division base northeast of Hama city. The evolution of the Tiger Forces into a more conventional division has further expanded Russia’s control over key SAA units — particularly offensive units and those stationed in northwestern Syria. Like the 5th Corps before it, the 25th Division now serves as an import tool for integrating militias from Homs, Hama, Idlib, and eastern Aleppo, as well as a path of recruitment within the Sunni areas of the aforementioned governorates recaptured by pro-regime forces in the latter half of the war.

But this shift into the more conventional 25th Division left the Russians without a reliable, smaller quick reaction force while also not filling the gap in the Russian proxy presence in northern Aleppo. The Turkish intervention in February 2020 and the subsequent Idlib ceasefire imposed on Russia and the Syrian regime a month later ended serious, war-time military operations for Damascus and Moscow. Both militaries have used the two quiet years since to continue their work rebuilding, retooling, and restructuring the array of pro-regime armed forces. It is in this context that Russia formed the 16th Storming Brigade in late June 2020.

Russia Finds a New Hammer

The first mention of the 16th Brigade on social media occurred on June 25, 2020. In October of that year, a member of the unit claimed the brigade fielded 1,000 soldiers. Many of these troops were pulled from the 25th Division and 5th Corps, though others came from various units across the SAA, including the Republican Guard. For example, one member of the group posted a picture in early July riding a tank on a flatbed truck with the caption that he had transferred from the 18th Division to the 16th Brigade.[17] The brigade operates some heavy armor, as evidenced by several videos over the past two years showing small convoys on the move. One such video, posted on March 1, 2021, showed five tanks, three BMPs (Soviet/Russian-built tracked infantry fighting vehicles), and three self-propelled guns. A picture posted by the same soldier in July 2020 showed 13 similarly arranged armored vehicles at a base. However, like the Tiger Forces, the 16th Brigade also heavily employs flatbed-mounted artillery and so-called “technicals,” pickup trucks mounted with heavy weapons such as anti-air cannons.

Videos and pictures posted by 16th Brigade soldiers throughout the fall of 2020 showed several gatherings geolocated to the large military base south of Asilah, in northwest Homs. However, according to a Syrian officer with ties to the unit, the group’s main base is near Aleppo city, where its administrative and leadership centers are housed, though units do frequently come to Hama for training. There are several possible reasons why Russia and the SAA may have chosen to base the brigade in Aleppo. First, this may have been viewed as a way to bolster Russian and SAA influence in an area dominated by Iran (though claims of Russian-Iranian competition are generally overblown). More significant is the strategic importance of Aleppo in any future hostilities. This may be one insight into how Russia plans to utilize the brigade. From Aleppo, the 16th Brigade is well placed to react to any escalations along the Turkish fronts of Afrin, Euphrates Shield, and Manbij, as well as to take a lead role in pushing southwest through the Aleppo-Idlib frontline should the ceasefire with the Islamist militant group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which operates in that area, ever collapse.

Another insight into Russia’s likely vision for the 16th Brigade comes from its choice of leadership for the new unit. Brig. Gen. Salah Abdullah, an Alawite born in 1967 in the town of Tayba, in the Safita countryside, and the long-standing number three of the Tiger Forces, was selected to lead the new brigade from day one. Unlike Suhail Hassan and the Tiger Forces’ Operations Commander Yunis Muhammad, Abdullah does not have an AFI background. Rather, he spent the early years of the war commanding Syrian Army units. According to one biography of him published on Facebook by his supporters, Abdullah joined the 7th Division after graduating from the military academy in the late 1980s, where he would eventually take command of the division’s 1st Battalion, by 2011. It is in this role that he “heroically” led the storming of the Omari Mosque in Dara’a, “cleansed” Hama city, and then moved to its countryside to fight in Kafr Nabouda, Lataminah, and Halfaya, before finally arriving in Latakia by late 2012. In 2013, he was selected to serve as the military official for the Tiger Forces in Aleppo, where he commanded the Khanasir road campaign and the liberation of Aleppo Central Prison. He would spend the next several years leading the Tiger Forces’ Aleppo campaigns throughout the city, including in Sheikh Najjar and Handarat, while also serving more broadly as the Tigers’ “military liaison” with the SAA.

His experiences in Khanasir and the Aleppo Central Prison demonstrate Abdullah’s extensive experience leading both his own forces and joint operations rooms in crucial, hard-fought offensive campaigns; while his work in 2011 and 2012 prove the commander has no qualms about murdering civilians and using collective punishment tactics to achieve the regime’s objectives. His selection as the head of the 16th Brigade, therefore, indicates that the Russians and the SAA view the brigade as filling the same strategic role that the Tiger Forces did all the way back in 2013, during the latter unit’s first major operations.

Abdullah received his initial assignment a year after the brigade was formed, returning to the place where he originally made a name for himself as a ruthless commander. In August 2021, Damascus launched its first major military operation in Dara’a since it had reclaimed the region from local rebel fighters in 2018.[18] In the three years since that offensive, Dara’a had been rocked by an increasingly violent insurgency — a mélange of ex-Free Syrian Army (FSA) cells, local criminals, and Islamic State insurgents, all on top of regular retaliatory killings by regime forces against former rebels. Previous attempts by the Assad regime to quell the insurgency did not have the support of Russia, whose generals had negotiated the reconciliation deals that saw the surrender of Dara’a in exchange for the pseudo-autonomy of many towns that now served to bolster the insurgents. But by August 2021, the attacks had become too frequent, and with the Idlib front appearing securely frozen, Russia greenlit an operation to retake several key cities.

Russia’s involvement was evident from day one. Video of an armored unit consisting of tanks, BMPs, and heavy artillery “traveling to Dara’a” was shared by members of the 16th Brigade on their private accounts on Aug. 24, 2021. Two days later, video of the same armored column, now explicitly labeled as belonging to the 16th Brigade, was disseminated more broadly by pro-regime channels. On Aug. 30, members of the 16th Brigade announced the first combat death from within the unit, while others shared a video of themselves engaged in a heavy firefight “several days ago” somewhere in Dara’a. Other SAA units — all of which were already stationed in the region — took part in the fighting; but it was the 16th Brigade that was the first to enter each town as they surrendered one by one. A video shared by Al Jazeera Syria showed Russian and 16th Brigade officers inside Dara’a city on Sept. 8, while pro-regime news pages and 16th Brigade social media posts showed members of the unit and vehicles bearing the brigade’s name in Yadouda on Sept. 14, Muzayrib on Sept. 16, and Tafas on Sept. 20. At least a part of these forces was led by Col. Jamal al-Din al-Ghajari, a battalion commander in the brigade.

With the surrender of these three towns and several neighborhoods of Dara’a city, the 16th Brigade withdrew back to its bases and positions in northern Syria. On Oct. 25, a 16th Brigade tanker who had regularly uploaded pictures of the unit’s armored vehicles in the south posted, “The mission in Dara’a is over.” Over the course of the next week, he would share several photos and videos of an armored column consisting of around 12 vehicles on its way back to the Aleppo countryside. This was the first — and so far, only — operation for the new unit. According to human rights organizations, the regime offensive left at least 22 civilians dead, mostly from indiscriminate shelling and heavy weapons fire.[19] Since then, the brigade has remained on the frontlines of northern Aleppo province, across from the Turkish army and its allied opposition forces. Soldiers and armored units of the 16th Brigade have been pictured around Idlib in 2020, and on the al-Bab and Manbij frontlines in 2021 and 2022.

The 16th Brigade’s emphasis on operations in the Aleppo countryside appears further cemented through discussions this summer about appointing Brig. Salah Abdullah as the deputy commander of the Republican Guard’s 30th Division. This division was formed in January 2017 to integrate all pro-regime units in Aleppo under one command following Damascus’ recapture of the city the month prior, and it now serves as the main military force in the city and its countryside. According to one officer interviewed by this author in August, the decision to appoint Abdullah to the division has not been confirmed yet; but if it is, he will almost certainly retain his role as the head of the 16th Brigade. Thus, the command chain between the brigade and the broader SAA forces in the northern Aleppo area will be solidified — an important step for improving combat effectiveness in the event of a future offensive.

What the unit does in the event of a Turkish offensive against Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) positions in Tel Rifaat or Manbij will be a key indicator for the Russian stance toward such an offensive. It is unlikely that Russia will risk severely damaging its newest, and somewhat small, proxy force, though Russian and Syrian leaderships may view a Turkish offensive as an excellent opportunity to battle harden the brigade for future battles. But while the brigade may be staffed with experienced officers and draw heavily from veteran soldiers, the unit would be decimated by Turkish air and artillery strikes, just like the other SAA units that fought against Turkey in Idlib in early 2020. It is not clear what incentive Russia or Damascus has for enduring such significant losses in a failed bid to stop a Turkish offensive that would ultimately be aimed only at SDF-held territory.

Furthermore, the long-term future of the brigade remains uncertain. What purpose does a small quick-reaction force serve in a frozen conflict? The longer the SAA goes without engaging in any serious military operations, the more likely it is that the 16th Brigade will simply be folded into the 5th Corps or 25th Division — both units that are also supported and commanded by Russia. After all, this has been the ultimate goal if the Russian military in Syria since forming the 4th Corps six years ago. Ideally, the Syrian army would not need stand-alone quick reaction forces but would rather be able to reconstitute its decimated special forces, or at least create specialized units within broader formations (such as the new Parachute Regiment of the 25th Division) — structures more in line with a proper state armed force. With the sudden storm of rumors and stories earlier this year of Russia sending Syrians to Ukraine, one might think the 16th Brigade would be a perfect fit for shoring up Russian lines in Kherson or Donbas. But as this author argued in March, at present there is neither evidence of, nor motivation for, sending Syrians to fight Russia’s war. Whatever happens to the 16th Brigade, its fate remains tied to Syria.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News