Despite many years of expanding cooperation and engagement between Beijing and Moscow, China’s record on trade, foreign direct investment, weapons sales, and military exercises after the invasion of Ukraine suggests that Beijing has not backed the Russian war effort in material terms. Although China has offered strong rhetorical support for Russia, it is trying, like many countries from the Global South, to straddle both East and West without sacrificing core interests. After seven months of war, what has been revealed about the Russia-China strategic partnership? While the record is mixed, China’s economic and military engagement with Russia provides little evidence of directly backing the war effort or flouting the Western-led sanctions regime. Instead, China’s record reveals a pattern of foreign policy hedging.

China’s Calculating and Balancing

Following the meeting of Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin at the Beijing Winter Olympics, a joint statement was published on February 4, 2022, famously stating that the Chinese-Russian friendship had “no limits.” This statement, which was the culmination of nearly eight years of warming Russian-Chinese relations, set off alarms in the West, given Russia’s massive military buildup along Ukraine’s borders. After Russian troops, tanks, missiles, and armored vehicles crossed into Ukrainian territory on February 24, many took the earlier pronouncement as evidence that Xi had prior knowledge of, and had even backed, the invasion of Ukraine.

This perception initially seemed to worry some Chinese officials, as Beijing appeared to walk back its fulsome Russian embrace in the aftermath of the invasion. Beijing’s Ambassador to Washington sought to reassure the American public with multiple U.S. media appearances that Xi had not given Putin the green light at the Winter Olympics to invade. In a Washington Post op-ed, Ambassador Qin Gang unequivocally wrote, “Assertions that China knew about, acquiesced to, or tacitly supported this war are purely disinformation.” Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng, in a major policy speech in May, categorically rejected the idea that China had endorsed the war in advance as “absurd.” However, despite these early reassurances, top Chinese officials belatedly and repeatedly characterized the war in pro-Russian terms, including blaming the “crisis” in Ukraine on NATO enlargement.

Beijing has been playing a balancing act, trying to save face and align with Russia while at the same time protecting its access to Western markets and finance. Avoiding any language critical of Moscow, Beijing has thus far curtailed activities that could trigger secondary sanctions from the West. While Russia has limited its reporting of official data since the start of the war, Chinese official data show adecline in commercial activity across key sectors, a pause in BRI investment, no increase in military training exercises, and no change in the pattern of military sales to Russia relative to the previous year.

Hence, as satisfying as teaming up with Russia to confront and challenge the United States might have seemed to Xi before the war, violating Western sanctions and jeopardizing China’s access to Europe and North America’s 30 trillion-dollar market appear too high a price to pay for a foreign policy alignment with Russia. Indeed, China’s foreign policy reflects some of the same constraints of many other states with special ties to, and interests in, Russia, including some states that are formally allied with the United States, like Turkey and Israel. However, China’s position is far from fixed, as several factors can alter the leadership’s current calculations of how best to advance its interests vis-à-vis Russia and the West.

Rhetoric Versus Reality

The official statements by Chinese Foreign Ministry officials and political leaders remain, for the most part, highly supportive of Russia’s position. On multiple occasions, Chinese officials have repeated their support for Russia’s revanchism, parroting Moscow’s talking points on the origins of the crisis. They have offered their recognition of “Russia’s legitimate security concerns” in the United Nations in the immediate aftermath of the invasion, and, like the censored Russian media, leaders have avoided using the words “war” and “invasion” in official statements.

Moreover, despite reaffirming the importance of the national sovereignty of all countries, Chinese leaders have referenced NATO enlargement as the cause of Russia’s invasion of its neighbor. For example, Xi criticized “some countries” that have “enlarged military alliances producing military conflicts” at the BRICS conference in June, although he made no reference to the war in his remarks following his meeting with Putin at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in September. Also linking the war to NATO enlargement, Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng in May identified NATO’s eastward expansion as the “root cause” of the crisis. Beijing’s direct and indirect references to NATO enlargement reinforce Moscow’s message and a key justification for the war. In response to this and other statements, Washington’s ambassador to China, Nicholas Burns, in a diplomatic forum in July, called on China’s Foreign Ministry spokespersons to stop spreading “Russian propaganda.” While the rhetorical support has damaged its relations with the West, China’s relationship with the United States has been in tatters for years.

Trade and Investment in 2022

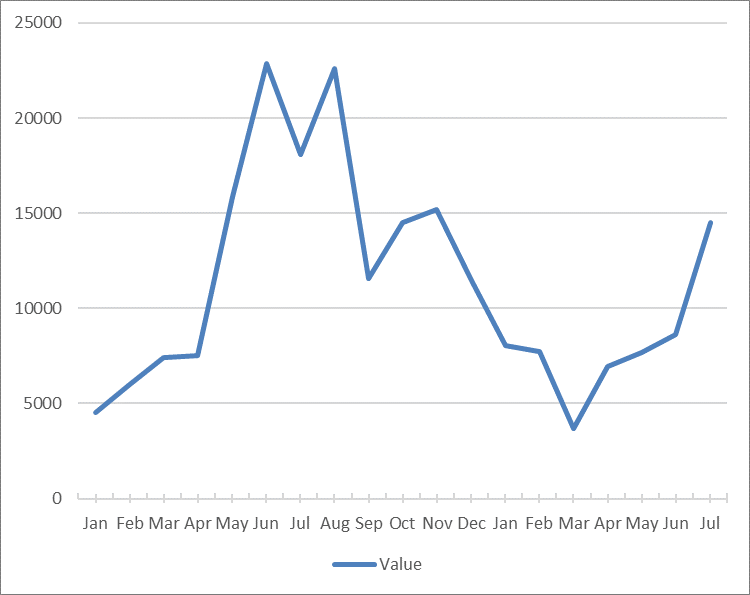

The rhetoric coming out of Beijing suggests a strong alignment with Russia, but China’s economic and military activity does not paint a similar picture. In terms of trade with Russia, China has not participated in the sanctions regime like many states, including several U.S. allies. Trade between Russia and China continues at levels similar to previous years, with increases in energy imports and decreases in many other sectors. Chinese exports of sensitive products have stagnated. For example, China’s semiconductor exports to Russia fell in March 2022 and later recovered to January’s pre-war levels in July. Importantly, China is exporting semiconductors to Russia at a much lower level in 2022 than in the period from May through December 2021. According to Chinese trade data, from May through December 2021, China exported $132.2 million worth of semiconductors to Russia—a monthly average value of $16.5 million. From January to July 2022, the total export value was only $57.2 million—a monthly average value of $8.2 million. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. China’s Semiconductor Exports to Russia ($ thousands; Jan 2021-Jul 2022)

In the case of Chinese exports to Russia of aircraft and spacecraft parts, except for a spike in June 2021 ($33 million), sales remained around or below $5 million since January 2021. See Figure 2 below. Despite a very substantial spike in Chinese exports of radar and radio navigation equipment in December 2021 (approximately $45 million), China’s official customs statistics show that export levels remain at $3.75-5.5 million per month, similar to most of 2021.

Figure 2. China’s Aircraft, Spacecraft, and Parts Exports to Russia ($ thousands)

In terms of fossil fuel imports from Russia to China, the growth is significant. China’s monthly fossil fuel imports have risen more than 50 percent from February to July ($4,606.4 million to $7,938.4 million), with a high point of $8,082.9 million in May 2022. See Figure 3 below. China, along with other countries like India, has benefited from purchases of Russian oil at very favorable terms, obtaining an “unprecedented” $35 discount on barrels of Russian Ural oil, “though the historical spread has rarely exceeded $5.”

That said, these energy purchases by China are compliant with Western sanctions, which do not ban oil and gas purchases. Although the United States has banned the import of Russian oil into the United States, EU countries continue to import Russian energy, with only minimal reductions. In particular, EU members reached a voluntary agreement to reduce gas imports by 15 percent, and the EU allows imports of oil delivered by pipelines, with gradual reductions of oil deliveries by sea taking effect over the course of 2022.

Figure 3. China’s Fossil Fuel Imports from Russia ($ millions; Jan 2021-Jul 2022)

Moreover, it is important to note that Chinese investment in Russia has contracted, suggesting both private and state-owned enterprises see investing in Russia as riskier than before the war. A Fudan University study reported that China has concluded no new investments in Russia through the Belt and Road Initiative in the first half of 2022, concentrating instead on the Middle East to avoid Western sanctions. Just last year, China concluded deals worth $2 billion with Russia in its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In fact, since 2013, BRI deals have reached this level of investment or higher most years; during the standout years of 2019, 2017, and 2015, Chinese investment and construction deals in Russia were worth in excess of $6 billion.

Moreover, these numbers do not include non-BRI lending from the China Development Bank and Eximbank, which are significant. In fact, from 2000-2017, China lent Russia $15 billion from Eximbank and $58 billion from the China Development Bank, according to AidData. While 2022 data from Eximbank or CDB are currently not available, the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) announced on March 3 that, due to the war, all of its activities relating to Russia and Belarus are “on hold and under review.”

Military Exercises and Weapons Sales

The pattern of military operations between Russia and China has, too, not changed significantly since the invasion. Russia and China have held three joint military exercises since February 2022. The first took place on May 24, the second on August 13, and the third on September 1-7. The first included Chinese and Russian bombers flying over the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea, and the Philippine Sea. The form and scale of this exercise were similar to former joint cruise missions held each year since 2019. The second exercise was part of the International Army Games, in which Russia and China jointly hosted multiple competitions for 37 countries, as in previous years. The third exercise in September, Vostok 2022, included multiple member countries from the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SOC). Again, this is part of a repeated pattern, given that China sent troops to the Vostok 2018 (and to the Tsentr exercises in 2019).

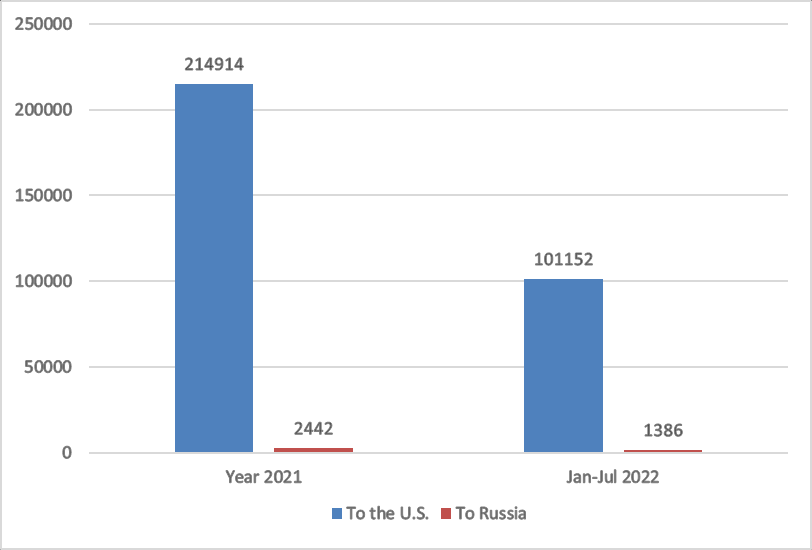

In terms of weapons and ammunition exports from China to Russia, there is no clear change from the previous year. The value of monthly weapons exports to Russia has been less than $0.7 million since January 2021. More importantly, in assessing China’s record of “choosing sides” between Russia and the West, it is useful to note that Chinese weapons exports to the United States are much greater than to Russia. From January to July 2022, China exported weapons worth $101.2 million to the United States while exporting $1.4 million to Russia during the same period. See Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. China’s Weapon/Ammo Exports ($ thousands)

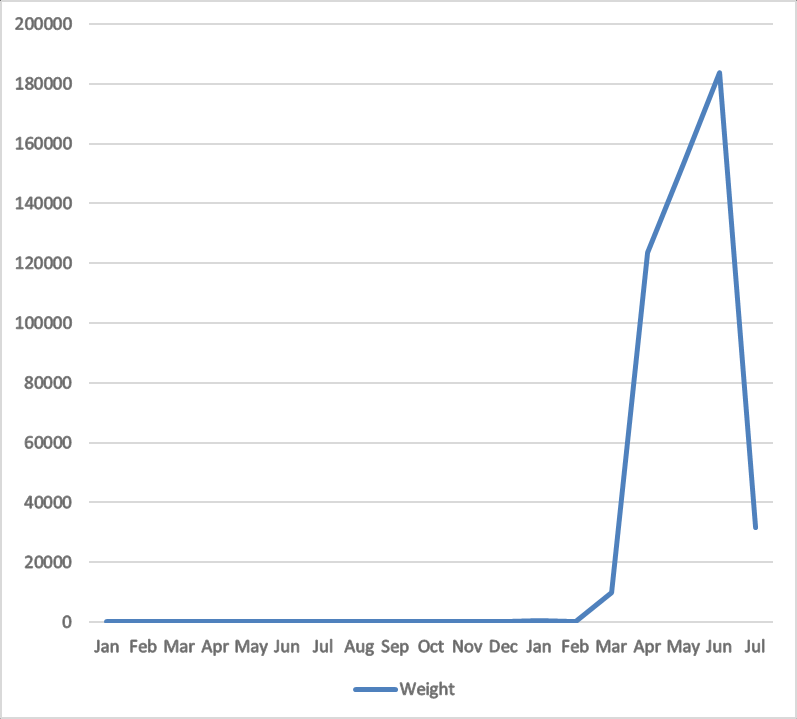

That said, the substantial growth of aluminum oxide exports attracted attention in the Western media, given the military applications of this material. From February to June 2022, Chinese exports of this material to Russia increased from 320.6 tons per month to 183,804.4 tons. However, a sharp decrease occurred in July, bringing down the overall weight of aluminum oxide exports to 31,473.1 tons for July. See Figure 5 below.

Figure 5. China’s Aluminum Oxide Exports to Russia (Tons; Jan 2021-Jul 2022)

In sum, the record of FDI, trade, military sales, and exercises does not provide evidence of China materially backing Russia over the West. The data comparing weapons exports to Russia versus the United States might, in fact, give the opposite impression. As of September 2022, China continues to import large quantities of discounted Russian oil and maintain similar levels of its weapons exports to Russia. The rise in aluminum oxide exports and spike in energy imports are key exceptions.

Beijing’s Balancing Act is Neither Unique Nor Set in Stone

China is one of many countries that avoids offending Russia in order to reap the benefits of a neutral (or positive) relationship while not running afoul of the Western-led sanctions. Many leaders, including those from countries that ally with the United States, have found themselves in serious conflict when navigating their relations with Russia and the United States since the start of the war. For example, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and sold Ukraine advanced weapons to Moscow’s great consternation; but Turkey did not impose economic sanctions on Russia. Turkey depends upon Russia and Ukraine for 80 percent of its grain and has its own security interests related to the Kurdish population living in Northern Syria. This requires that Turkey maintain good relations with Russia, whose military presence in Syria remains substantial. In contrast to Beijing, however, Ankara has adopted a particular strategy of hedging that includes positioning itself as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia, as seen in the deal mediated in August 2022 to allow for the export of Ukrainian grain.

In a similar vein, Israel—a strong U.S. ally—has sought the position of mediator in the war as a way to cope with its incompatible foreign policy interests vis-à-vis Russia and the United States. Although Israel is dependent on the United States for its overall security, it remains cautious in how it relates to Russia. Israel relies upon Russian acquiescence of its (unacknowledged) attacks against Hezbollah targets in Syria. Furthermore, Israel wants to avoid jeopardizing its Right of Return Emigration Program for the 600,000 eligible Jews residing in Russia. Given these core interests requiring good relations with Russia, Israel has only supplied Ukraine with humanitarian relief and very limited defensive weapons, like helmets, withholding the more high-tech weapons that Washington would like Israel to share.

Certainly, Beijing is more critical of the United States and references the importance of NATO enlargement in official rhetoric, but China shares important similarities with many tentative countries. In fact, all of the BRICS countries except Brazil abstained in the vote on the United Nations Resolution condemning Russia that passed on March 2. At the same time, it should be noted that China and the other BRICS countries did not vote against the resolution condemning Russia, as did Syria, North Korea, and Belarus. While it remains unclear whether the West’s sanctions or the violation of Ukrainian sovereignty are driving these abstentions for the BRICS countries, what is clear is that China is hardly exceptional in its efforts to protect its conflicting foreign policy interests.

While China’s position can be characterized as one of hedging, certain developments could tip the balance. Indeed, if Putin’s hold on power falters, either due to further losses on the battlefield or due to a massive backlash against Russia’s mobilization of troops, China may shift support away from Russia. As Fiona Hill asserts, Xi does not want to be seen backing a loser. Moreover, if Chinese economic growth slows even further due to its zero-COVID policy and related shifts in global supply chains, Beijing may want to take even more care to avoid retaliatory sanctions. It has already lost support in Europe due to its position in Ukraine—a significant cost of Xi’s position in this war. As Minxin Pei writes, the Europeans had been reluctant to get dragged into the burgeoning U.S.-China Cold War, but due to China’s position, the Europeans have moved closer to the United States at China’s expense. Finally, if Russia chooses to use a tactical nuclear weapon, China would likely withdraw all rhetorical support for Moscow and respond economically.

On the flip side, China’s support for Russia could increase, depending on how the United States handles the Taiwan issue. The strategic partnership between Russia and China is based on the shared desire to push back on a unipolar world, led by the United States. If the U.S. Congress passes the Taiwan Policy Act as is, Beijing’s grievances toward the West may intensify and bring about a further rapprochement between Russia and China. As a result, China may offer new material support to Russia’s war effort directly or indirectly through a third party, like Iran or North Korea. For now, however, China must continue its effort to hedge and hope that its position does not require it to absorb further blows to its core interests.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News